Difference between revisions of "Journal:Costs of mandatory cannabis testing in California"

Shawndouglas (talk | contribs) (Saving and adding more.) |

Shawndouglas (talk | contribs) (Saving and adding more.) |

||

| Line 25: | Line 25: | ||

==Introduction== | ==Introduction== | ||

Since California's [[wikipedia:1996 California Proposition 215|Compassionate Use Act of 1996]], [[wikipedia:Cannabis|cannabis]] has been legally available—under state but not federal law—to those with medical permission. Until 2018, however, no statewide regulations governed the production, manufacturing, and sale of cannabis. Prior to development and enforcement of statewide regulations, there were no testing requirements for chemicals used during cannabis cultivation and processing, including [[wikipedia:Pesticide|pesticides]], [[wikipedia:Fertilizer|fertilizers]], or [[wikipedia:Solvent|solvents]].<ref name="LindseyMedical12">{{cite web |url=https://www.canorml.org/prop/CRB_Pesticides_on_Medical_Marijuana_Report.pdf |format=PDF |title=Medical Marijuana Cultivation and Policy Gaps |author=Lindsey, T.D. |publisher=California Research Bureau |date=10 April 2012}}</ref><ref name="StoneCanna14">{{cite journal |title=Cannabis, pesticides and conflicting laws: The dilemma for legalized States and implications for public health |journal=Regulatory Toxicology and Pharmacology |author=Stone, D. |volume=69 |issue=3 |pages=284–8 |year=2014 |doi=10.1016/j.yrtph.2014.05.015 |pmid=24859075}}</ref> Residues were common in the legal cannabis supply; a 2017 investigation found that 93% of 44 samples collected from 15 cannabis retailers in California contained pesticide residues.<ref name="GroverPest17">{{cite web |url=https://www.nbclosangeles.com/news/local/I-Team-Marijuana-Pot-Pesticide-California-414536763.html |title=Pesticides and Pot: What's California Smoking? |author=Grover, J.; Glasser, M. |work=NBC4 Los Angeles |date=22 February 2017}}</ref> Some studies of data from the unregulated period suggest a relationship between cannabis consumption and exposure to [[wikipedia:Heavy metals|heavy metals]]<ref name="MoirAComp08">{{cite journal |title=A comparison of mainstream and sidestream marijuana and tobacco cigarette smoke produced under two machine smoking conditions |journal=Chemical Research in Toxicology |author=Moir, D.; Rickert, W.S.; Levasseur, G. et al. |volume-21 |issue=2 |pages=494–502 |year=2008 |doi=10.1021/tx700275p |pmid=18062674}}</ref><ref name="SinganiManure12">{{cite journal |title=Manure Application and Cannabis Cultivation Influence on Speciation of Lead and Cadmium by Selective Sequential Extraction |journal=Soil and Sediment Contamination |author=Singani, A.A.S.; Ahmadi, P. |volume-21 |issue=3 |pages=305–21 |year=2012 |doi=10.1080/15320383.2012.664186}}</ref>, while others demonstrate that potentially harmful [[wikipedia:Microorganism|microorganisms]] may colonize the flowers of the ''Cannabis'' plant.<ref name="McLarenCanna08">{{cite journal |title=Cannabis potency and contamination: A review of the literature |journal=Addiction |author=McLaren, J.; Swift, W.; Dillon, P. et al. |volume=103 |issue=7 |pages=1100–9 |year=2008 |doi=10.1111/j.1360-0443.2008.02230.x |pmid=18494838}}</ref><ref name="McPartlandContam02">{{cite book |chapter=Chapter 30: Contaminants and Adulterants in Herbal Cannabis |title=Cannabis and Cannabinoids: Pharmacology, Toxicology, and Therapeutic Potential |author=McPartland, J.M. |editor=Grotenhermen, F.; Russo, E. |publisher=The Haworth Press |pages=337–344 |year=2002 |isbn=9780789015082}}</ref><ref name="McPartlandContam17">{{cite book |chapter=Contaminants of Concern in Cannabis: Microbes, Heavy Metals and Pesticides |title=''Cannabis sativa'' L. - Botany and Biotechnology |author=McPartland, J.M., McKernan, K.J. |editor=Chandra, S.; Lata, H.; ElSohly, M. |publisher=Springer |pages=457–74 |year=2017 |isbn=9783319545646}}</ref><ref name="RuchlemerInhaled15">{{cite journal |title=Inhaled medicinal cannabis and the immunocompromised patient |journal=Supportive Care in Cancer |author=Ruchlemer, R.; Amit-Kohn, M.; Raveh, D. et al. |volume=23 |issue=3 |pages=819-22 |year=2015 |doi=10.1007/s00520-014-2429-3 |pmid=25216851}}</ref> A 2017 study raised concerns that in immunocompromised patients, use of cannabis contaminated with [[wikipedia:Pathogen|pathogens]] may directly affect the respiratory system, especially when cannabis products are inhaled.<ref name="ThompsonAMicro">{{cite journal |title=A microbiome assessment of medical marijuana |journal=Clinical Microbiology and Infection |author=Thompson, G.R. 3rd; Tuscano, J.M.; Dennis, M. et al. |volume=23 |issue=4 |pages=269-270 |year=2017 |doi=10.1016/j.cmi.2016.12.001 |pmid=27956269}}</ref> | Since California's [[wikipedia:1996 California Proposition 215|Compassionate Use Act of 1996]], [[wikipedia:Cannabis|cannabis]] has been legally available—under state but not federal law—to those with medical permission. Until 2018, however, no statewide regulations governed the production, manufacturing, and sale of cannabis. Prior to development and enforcement of statewide regulations, there were no testing requirements for chemicals used during cannabis cultivation and processing, including [[wikipedia:Pesticide|pesticides]], [[wikipedia:Fertilizer|fertilizers]], or [[wikipedia:Solvent|solvents]].<ref name="LindseyMedical12">{{cite web |url=https://www.canorml.org/prop/CRB_Pesticides_on_Medical_Marijuana_Report.pdf |format=PDF |title=Medical Marijuana Cultivation and Policy Gaps |author=Lindsey, T.D. |publisher=California Research Bureau |date=10 April 2012}}</ref><ref name="StoneCanna14">{{cite journal |title=Cannabis, pesticides and conflicting laws: The dilemma for legalized States and implications for public health |journal=Regulatory Toxicology and Pharmacology |author=Stone, D. |volume=69 |issue=3 |pages=284–8 |year=2014 |doi=10.1016/j.yrtph.2014.05.015 |pmid=24859075}}</ref> Residues were common in the legal cannabis supply; a 2017 investigation found that 93% of 44 samples collected from 15 cannabis retailers in California contained pesticide residues.<ref name="GroverPest17">{{cite web |url=https://www.nbclosangeles.com/news/local/I-Team-Marijuana-Pot-Pesticide-California-414536763.html |title=Pesticides and Pot: What's California Smoking? |author=Grover, J.; Glasser, M. |work=NBC4 Los Angeles |date=22 February 2017}}</ref> Some studies of data from the unregulated period suggest a relationship between cannabis consumption and exposure to [[wikipedia:Heavy metals|heavy metals]]<ref name="MoirAComp08">{{cite journal |title=A comparison of mainstream and sidestream marijuana and tobacco cigarette smoke produced under two machine smoking conditions |journal=Chemical Research in Toxicology |author=Moir, D.; Rickert, W.S.; Levasseur, G. et al. |volume-21 |issue=2 |pages=494–502 |year=2008 |doi=10.1021/tx700275p |pmid=18062674}}</ref><ref name="SinganiManure12">{{cite journal |title=Manure Application and Cannabis Cultivation Influence on Speciation of Lead and Cadmium by Selective Sequential Extraction |journal=Soil and Sediment Contamination |author=Singani, A.A.S.; Ahmadi, P. |volume-21 |issue=3 |pages=305–21 |year=2012 |doi=10.1080/15320383.2012.664186}}</ref>, while others demonstrate that potentially harmful [[wikipedia:Microorganism|microorganisms]] may colonize the flowers of the ''Cannabis'' plant.<ref name="McLarenCanna08">{{cite journal |title=Cannabis potency and contamination: A review of the literature |journal=Addiction |author=McLaren, J.; Swift, W.; Dillon, P. et al. |volume=103 |issue=7 |pages=1100–9 |year=2008 |doi=10.1111/j.1360-0443.2008.02230.x |pmid=18494838}}</ref><ref name="McPartlandContam02">{{cite book |chapter=Chapter 30: Contaminants and Adulterants in Herbal Cannabis |title=Cannabis and Cannabinoids: Pharmacology, Toxicology, and Therapeutic Potential |author=McPartland, J.M. |editor=Grotenhermen, F.; Russo, E. |publisher=The Haworth Press |pages=337–344 |year=2002 |isbn=9780789015082}}</ref><ref name="McPartlandContam17">{{cite book |chapter=Contaminants of Concern in Cannabis: Microbes, Heavy Metals and Pesticides |title=''Cannabis sativa'' L. - Botany and Biotechnology |author=McPartland, J.M., McKernan, K.J. |editor=Chandra, S.; Lata, H.; ElSohly, M. |publisher=Springer |pages=457–74 |year=2017 |isbn=9783319545646}}</ref><ref name="RuchlemerInhaled15">{{cite journal |title=Inhaled medicinal cannabis and the immunocompromised patient |journal=Supportive Care in Cancer |author=Ruchlemer, R.; Amit-Kohn, M.; Raveh, D. et al. |volume=23 |issue=3 |pages=819-22 |year=2015 |doi=10.1007/s00520-014-2429-3 |pmid=25216851}}</ref> A 2017 study raised concerns that in immunocompromised patients, use of cannabis contaminated with [[wikipedia:Pathogen|pathogens]] may directly affect the respiratory system, especially when cannabis products are inhaled.<ref name="ThompsonAMicro">{{cite journal |title=A microbiome assessment of medical marijuana |journal=Clinical Microbiology and Infection |author=Thompson, G.R. 3rd; Tuscano, J.M.; Dennis, M. et al. |volume=23 |issue=4 |pages=269-270 |year=2017 |doi=10.1016/j.cmi.2016.12.001 |pmid=27956269}}</ref> | ||

The currently prevailing statutes governing cannabis testing are contained in California Senate Bill 94, the Medicinal and Adult-Use Cannabis Regulation and Safety Act (MAUCRSA) of 2017, which brought together all of California's previous cannabis legislation, including Proposition 64, the [[wikipedia:Adult Use of Marijuana Act|Adult Use of Marijuana Act of 2016]] (AUMA). Since MAUCRSA, state agencies have propagated regulations for both [[wikipedia:Medical cannabis|medical use]] and adult use (that is, use for nonmedical purposes). MAUCRSA amends various sections of the California Business and Professions Code, Health and Safety Code, Food and Agricultural Code, Revenue and Taxation Code, and Water Code, introducing a new statewide structure for the governance of the cannabis industry, as well as a system by which the state may collect licensing and enforcement fees and penalties from cannabis businesses. A significant portion of MAUCRSA is comprised of testing rules that aim to certify cannabis safety.<ref name="BCCCalif18">{{cite web |url=https://www.bcc.ca.gov/law_regs/cannabis_text.pdf |format=PDF |title=California Code of Regulations, Title 15, Division 42, Bureau of Cannabis Control |author=California Bureau of Cannabis Control |date=October 2018 |accessdate=12 November 2018}}</ref> | |||

These rules, however, may increase the production cost and therefore the retail price of tested cannabis, thereby reducing demand for legal cannabis in California. Thus it is important to understand the costs of cannabis testing relative to the value of generating a safer product. This article evaluates the challenges of safety testing regulations for cannabis in California. | |||

We first review maximum allowable tolerance levels—that is, the amount of contaminants permitted in a sample—under the state's cannabis testing regulations and compare them with tolerance levels for other food and agricultural products produced in California. We then briefly compare testing regimes and rejection rates in other states where medical and recreational use is permitted. Finally, we use primary data from California's major cannabis testing laboratories and from several cannabis testing equipment manufacturers, as well as a variety of expert opinions, to estimate the cost per pound of testing under the state's framework for the cannabis business (taking into account the geographical configuration of the industry). We conclude by discussing implications of this research and potential regulatory changes. | |||

==Tests for contaminates and potency== | |||

Since July 1, 2018, all cannabis products have been required to pass several tests before they can be sold legally in California. The specific test for each batch of cannabis depends on product type. Types include (a) dried flowers (sometimes in “pre-rolled,” consumer-ready form); (b) edibles (for example cookies, gummy bears, and beverages); (c) vape-pen cartridges containing cannabis oil; and (d) a wide variety of other processed cannabis goods, including tinctures, topicals (such as lotions, lip balms, and creams), and cannabis in crystallized, wax, or solid hashish form. | |||

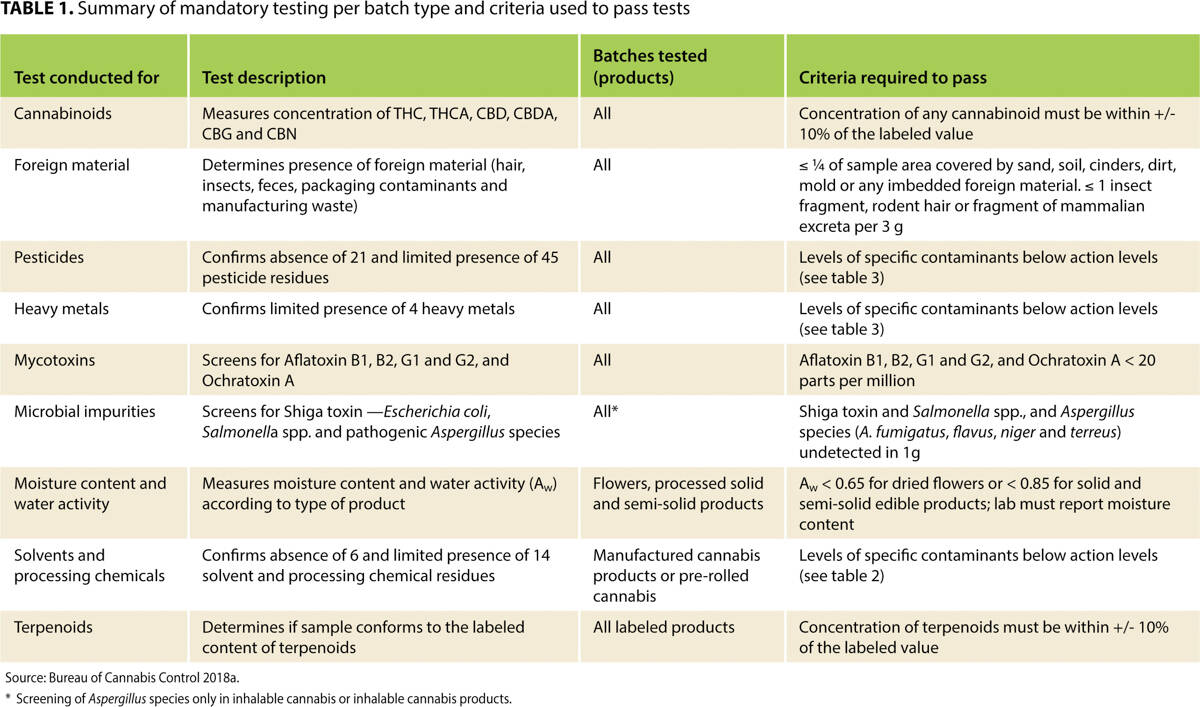

In order to enter the market legally, all these products must be tested for [[wikipedia:Cannabinoid|cannabinoids]] and a large variety of contaminants. Table 1 shows the substances measured in each test (for example, cannabinoids or pesticides), provides a description of each test, and specifies the products to which the test applies and the criteria for passing the test. Most tests—such as those for potency, presence of foreign materials, pesticides, heavy metals, [[wikipedia:Mycotoxin|mycotoxins]], microbial impurities, and [[wikipedia:Terpenoid|terpenoids]]—apply to all batches. Moisture tests, however, apply only to flowers and solid or semi-solid products, while tests for solvents or processing chemicals apply only to processed or “manufactured” products. That is, the specifics of each test depend on which cannabis product is tested. | |||

[[File:Tab1 Valdes-Donoso CaliforniaAg2019 73-3.jpg|1000px]] | |||

{{clear}} | |||

{| | |||

| STYLE="vertical-align:top;"| | |||

{| border="0" cellpadding="5" cellspacing="0" width="1000px" | |||

|- | |||

| style="background-color:white; padding-left:10px; padding-right:10px;"| <blockquote>'''Tab. 1''' Summary of mandatory testing per batch type and criteria used to pass tests</blockquote> | |||

|- | |||

|} | |||

|} | |||

Independent, licensed testing laboratories are responsible for receiving samples for testing from licensed distributors. The laboratories then conduct a full set of analyses, following the criteria established by MAUCRSA and specified by regulations. Laboratories must deliver to distributors a certificate of analysis indicating the results (pass or fail) of each analytical test. A batch must pass all required tests before it can be released to retailers. | |||

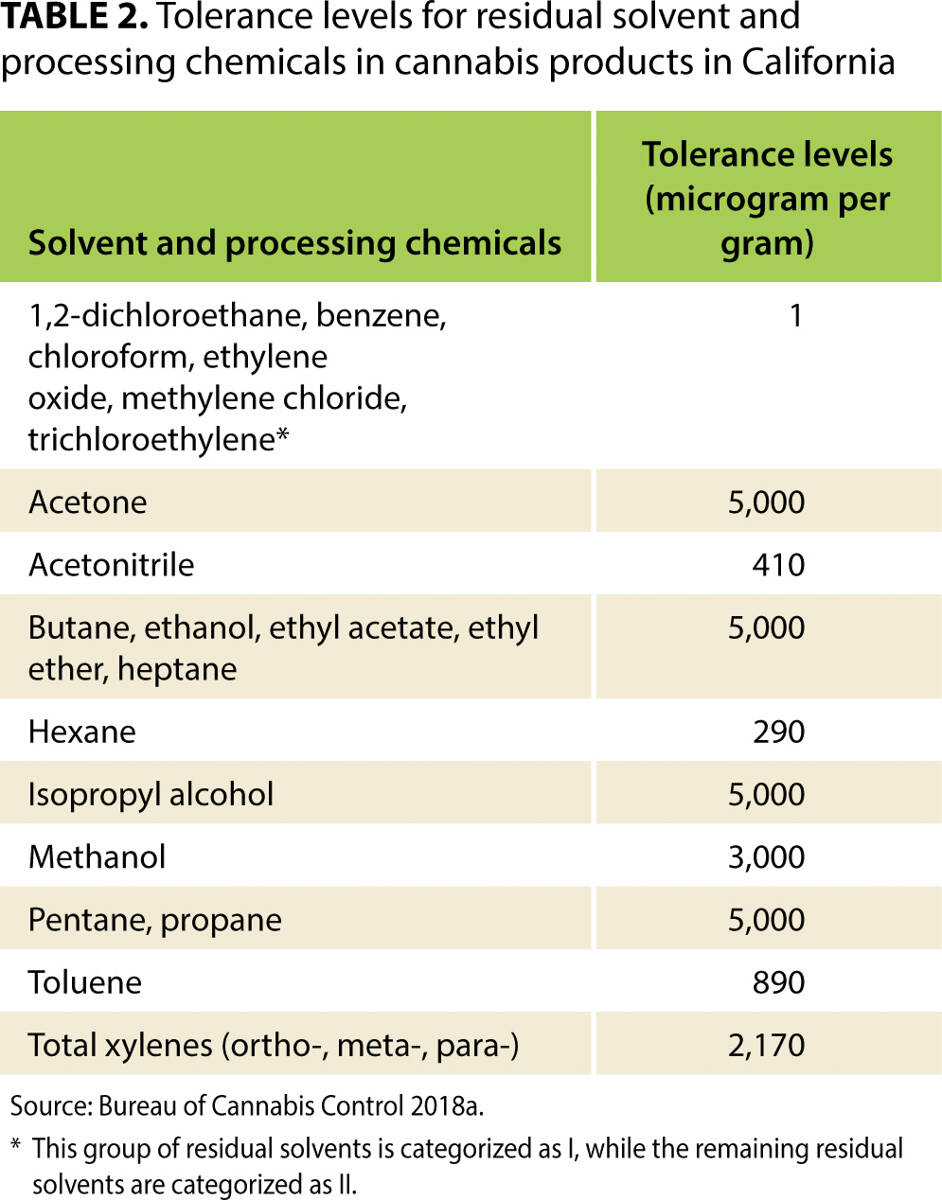

Table 2 shows a list of residual solvents and processing chemicals, with the maximum permitted tolerance (action) levels for legal cannabis. Tests evaluate two groups of solvents and processing chemicals (categories I and II), with a very low tolerance established (1.0 microgram per gram) for those in category I. | |||

[[File:Tab2 Valdes-Donoso CaliforniaAg2019 73-3.jpg|400px|left]] | |||

{{clear}} | |||

{| | |||

| STYLE="vertical-align:top;"| | |||

{| border="0" cellpadding="5" cellspacing="0" width="400px" | |||

|- | |||

| style="background-color:white; padding-left:10px; padding-right:10px;"| <blockquote>'''Tab. 2''' Tolerance levels for residual solvent and processing chemicals in cannabis products in California</blockquote> | |||

|- | |||

|} | |||

|} | |||

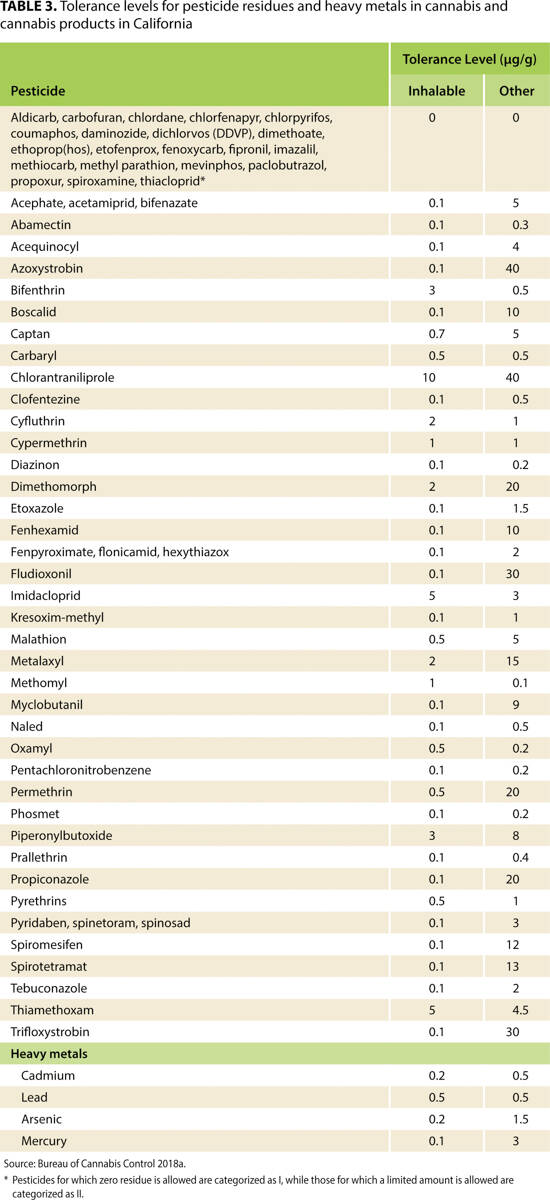

Table 3 shows tolerance levels for pesticide residues and heavy metals. The maximum permitted tolerance levels for pesticide residues are particularly tight when compared with tolerance levels for other agricultural products in California. For many pesticides, the maximum residual level is zero, meaning that very stringent tests are required and that no trace of the chemical may be found. Among pesticides with allowable limits above zero, the tolerance levels for inhalable products are particularly low. In some cases, tolerance levels for inhalable products are one-four-hundredth the levels for other products. | |||

[[File:Tab3 Valdes-Donoso CaliforniaAg2019 73-3.jpg|550px|left]] | |||

{{clear}} | |||

{| | |||

| STYLE="vertical-align:top;"| | |||

{| border="0" cellpadding="5" cellspacing="0" width="550px" | |||

|- | |||

| style="background-color:white; padding-left:10px; padding-right:10px;"| <blockquote>'''Tab. 3''' Tolerance levels for pesticide residues and heavy metals in cannabis and cannabis products in California</blockquote> | |||

|- | |||

|} | |||

|} | |||

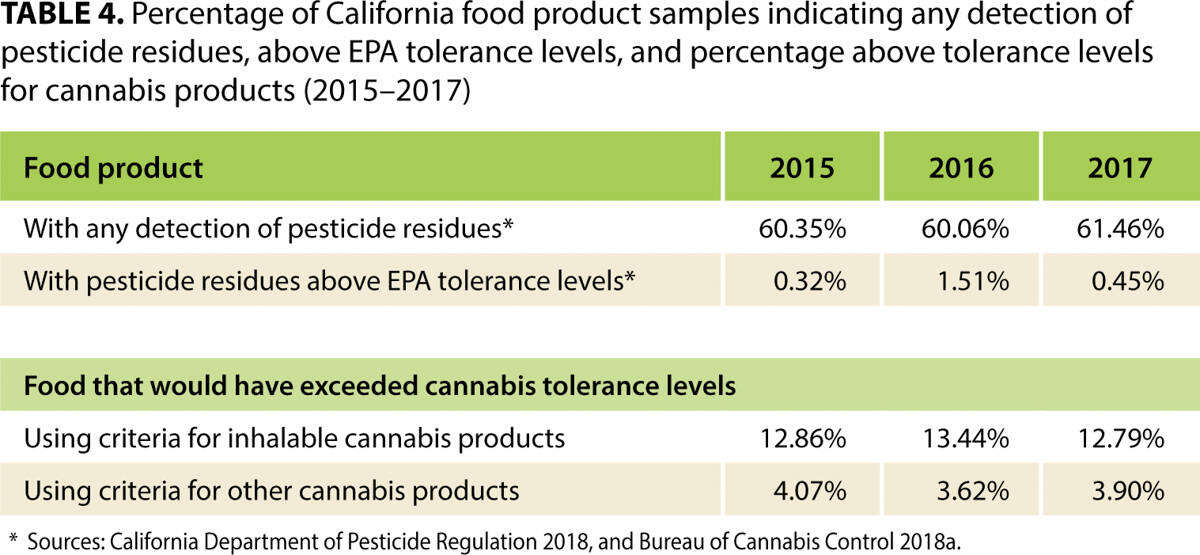

To help interpret the cannabis tolerances, it is helpful to consider them in the context of food safety testing. The top row of Table 4 shows, based on more than 7,000 samples, the percentage of California food products in which, from 2015 to 2017, any pesticide residues were detected (California Department of Pesticide Regulation 2018). These percentages were above 60%. The second row of Table 4 shows that, despite the high share of food products in which some pesticide residue was detectable, only 1.51% of samples in 2016 contained pesticide residue above tolerance levels set by the [[United States Environmental Protection Agency|U.S. Environmental Protection Agency]] (EPA), and only 0.45% exceeded those levels in 2017. The bottom panels of Table 4 show that, of the 7,000 samples tested, more than 12% of 2017 samples would have been above California's product tolerance limits for inhalable cannabis. More than 3% of the 2017 samples would have exceeded even the less stringent tolerance levels established for other (non-inhalable) cannabis products. As shown in Table 4, similar results apply to the samples for the other two years. | |||

[[File:Tab4 Valdes-Donoso CaliforniaAg2019 73-3.jpg|600px|left]] | |||

{{clear}} | |||

{| | |||

| STYLE="vertical-align:top;"| | |||

{| border="0" cellpadding="5" cellspacing="0" width="600px" | |||

|- | |||

| style="background-color:white; padding-left:10px; padding-right:10px;"| <blockquote>'''Tab. 4''' Percentage of California food product samples indicating any detection of pesticide residues, above EPA tolerance levels, and percentage above tolerance levels for cannabis products (2015–2017)</blockquote> | |||

|- | |||

|} | |||

|} | |||

==Costs of cannabis testing== | |||

==References== | ==References== | ||

| Line 30: | Line 101: | ||

==Notes== | ==Notes== | ||

This presentation is faithful to the original, with only a few minor changes to presentation. Some grammar and punctuation was cleaned up to improve readability | This presentation is faithful to the original, with only a few minor changes to presentation. Some grammar and punctuation was cleaned up to improve readability. In the original, references appear alphabetically; here they appear in order of appearance, by wiki design. In the original an image from ShutterStock was included; it was not added here because its not clear if the image can technically be included as Creative Commons content. Otherwise, in accordance with the NoDerivatives portion of the original license, nothing else has been changed. | ||

<!--Place all category tags here--> | <!--Place all category tags here--> | ||

Revision as of 21:21, 16 September 2019

| Full article title | Costs of mandatory cannabis testing in California |

|---|---|

| Journal | California Agriculture |

| Author(s) | Valdes-Donoso, Pablo; Sumner, Daniel A.; Goldstein, Robin |

| Author affiliation(s) | University of California Agricultural Issues Center, UC Davis |

| Primary contact | Email: pvaldesdonoso at ucdavis dot edu |

| Year published | 2019 |

| Volume and issue | 73(3) |

| Page(s) | 154–60 |

| DOI | 10.3733/ca.2019a0014 |

| ISSN | 0008-0845 |

| Distribution license | Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International |

| Website | http://calag.ucanr.edu/archive/?article=ca.2019a0014 |

| Download | http://calag.ucanr.edu/archive/?type=pdf&article=ca.2019a0014 (PDF) |

Abstract

Every batch of cannabis sold legally in California must be tested for more than 100 contaminants. These contaminants include 66 pesticides, for 21 of which the state's tolerance is zero. For many other substances, tolerance levels are much lower than those allowed for food products in California. This article reviews the state's testing [[Regulatory compliance|regulations] in context—including maximum allowable tolerance levels—and uses primary data collected from California's major cannabis testing laboratories and several cannabis testing equipment manufacturers, as well as a variety of expert opinions, to estimate the cost per pound of testing under the state's framework. We also estimate the cost of collecting samples, which depends on the distance between cannabis distributors and laboratories. We find that, if a batch fails mandatory tests, the value of cannabis that must be destroyed accounts for a large share of total testing costs, more than the cost of the tests that laboratories perform. Findings from this article will help readers understand the effects of California's testing regime on the price of legal cannabis in the state, and understand how testing may add value to products that have passed a series of tests that aim to validate their safety.

Introduction

Since California's Compassionate Use Act of 1996, cannabis has been legally available—under state but not federal law—to those with medical permission. Until 2018, however, no statewide regulations governed the production, manufacturing, and sale of cannabis. Prior to development and enforcement of statewide regulations, there were no testing requirements for chemicals used during cannabis cultivation and processing, including pesticides, fertilizers, or solvents.[1][2] Residues were common in the legal cannabis supply; a 2017 investigation found that 93% of 44 samples collected from 15 cannabis retailers in California contained pesticide residues.[3] Some studies of data from the unregulated period suggest a relationship between cannabis consumption and exposure to heavy metals[4][5], while others demonstrate that potentially harmful microorganisms may colonize the flowers of the Cannabis plant.[6][7][8][9] A 2017 study raised concerns that in immunocompromised patients, use of cannabis contaminated with pathogens may directly affect the respiratory system, especially when cannabis products are inhaled.[10]

The currently prevailing statutes governing cannabis testing are contained in California Senate Bill 94, the Medicinal and Adult-Use Cannabis Regulation and Safety Act (MAUCRSA) of 2017, which brought together all of California's previous cannabis legislation, including Proposition 64, the Adult Use of Marijuana Act of 2016 (AUMA). Since MAUCRSA, state agencies have propagated regulations for both medical use and adult use (that is, use for nonmedical purposes). MAUCRSA amends various sections of the California Business and Professions Code, Health and Safety Code, Food and Agricultural Code, Revenue and Taxation Code, and Water Code, introducing a new statewide structure for the governance of the cannabis industry, as well as a system by which the state may collect licensing and enforcement fees and penalties from cannabis businesses. A significant portion of MAUCRSA is comprised of testing rules that aim to certify cannabis safety.[11]

These rules, however, may increase the production cost and therefore the retail price of tested cannabis, thereby reducing demand for legal cannabis in California. Thus it is important to understand the costs of cannabis testing relative to the value of generating a safer product. This article evaluates the challenges of safety testing regulations for cannabis in California.

We first review maximum allowable tolerance levels—that is, the amount of contaminants permitted in a sample—under the state's cannabis testing regulations and compare them with tolerance levels for other food and agricultural products produced in California. We then briefly compare testing regimes and rejection rates in other states where medical and recreational use is permitted. Finally, we use primary data from California's major cannabis testing laboratories and from several cannabis testing equipment manufacturers, as well as a variety of expert opinions, to estimate the cost per pound of testing under the state's framework for the cannabis business (taking into account the geographical configuration of the industry). We conclude by discussing implications of this research and potential regulatory changes.

Tests for contaminates and potency

Since July 1, 2018, all cannabis products have been required to pass several tests before they can be sold legally in California. The specific test for each batch of cannabis depends on product type. Types include (a) dried flowers (sometimes in “pre-rolled,” consumer-ready form); (b) edibles (for example cookies, gummy bears, and beverages); (c) vape-pen cartridges containing cannabis oil; and (d) a wide variety of other processed cannabis goods, including tinctures, topicals (such as lotions, lip balms, and creams), and cannabis in crystallized, wax, or solid hashish form.

In order to enter the market legally, all these products must be tested for cannabinoids and a large variety of contaminants. Table 1 shows the substances measured in each test (for example, cannabinoids or pesticides), provides a description of each test, and specifies the products to which the test applies and the criteria for passing the test. Most tests—such as those for potency, presence of foreign materials, pesticides, heavy metals, mycotoxins, microbial impurities, and terpenoids—apply to all batches. Moisture tests, however, apply only to flowers and solid or semi-solid products, while tests for solvents or processing chemicals apply only to processed or “manufactured” products. That is, the specifics of each test depend on which cannabis product is tested.

|

Independent, licensed testing laboratories are responsible for receiving samples for testing from licensed distributors. The laboratories then conduct a full set of analyses, following the criteria established by MAUCRSA and specified by regulations. Laboratories must deliver to distributors a certificate of analysis indicating the results (pass or fail) of each analytical test. A batch must pass all required tests before it can be released to retailers.

Table 2 shows a list of residual solvents and processing chemicals, with the maximum permitted tolerance (action) levels for legal cannabis. Tests evaluate two groups of solvents and processing chemicals (categories I and II), with a very low tolerance established (1.0 microgram per gram) for those in category I.

|

Table 3 shows tolerance levels for pesticide residues and heavy metals. The maximum permitted tolerance levels for pesticide residues are particularly tight when compared with tolerance levels for other agricultural products in California. For many pesticides, the maximum residual level is zero, meaning that very stringent tests are required and that no trace of the chemical may be found. Among pesticides with allowable limits above zero, the tolerance levels for inhalable products are particularly low. In some cases, tolerance levels for inhalable products are one-four-hundredth the levels for other products.

|

To help interpret the cannabis tolerances, it is helpful to consider them in the context of food safety testing. The top row of Table 4 shows, based on more than 7,000 samples, the percentage of California food products in which, from 2015 to 2017, any pesticide residues were detected (California Department of Pesticide Regulation 2018). These percentages were above 60%. The second row of Table 4 shows that, despite the high share of food products in which some pesticide residue was detectable, only 1.51% of samples in 2016 contained pesticide residue above tolerance levels set by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), and only 0.45% exceeded those levels in 2017. The bottom panels of Table 4 show that, of the 7,000 samples tested, more than 12% of 2017 samples would have been above California's product tolerance limits for inhalable cannabis. More than 3% of the 2017 samples would have exceeded even the less stringent tolerance levels established for other (non-inhalable) cannabis products. As shown in Table 4, similar results apply to the samples for the other two years.

|

Costs of cannabis testing

References

- ↑ Lindsey, T.D. (10 April 2012). "Medical Marijuana Cultivation and Policy Gaps" (PDF). California Research Bureau. https://www.canorml.org/prop/CRB_Pesticides_on_Medical_Marijuana_Report.pdf.

- ↑ Stone, D. (2014). "Cannabis, pesticides and conflicting laws: The dilemma for legalized States and implications for public health". Regulatory Toxicology and Pharmacology 69 (3): 284–8. doi:10.1016/j.yrtph.2014.05.015. PMID 24859075.

- ↑ Grover, J.; Glasser, M. (22 February 2017). "Pesticides and Pot: What's California Smoking?". NBC4 Los Angeles. https://www.nbclosangeles.com/news/local/I-Team-Marijuana-Pot-Pesticide-California-414536763.html.

- ↑ Moir, D.; Rickert, W.S.; Levasseur, G. et al. (2008). "A comparison of mainstream and sidestream marijuana and tobacco cigarette smoke produced under two machine smoking conditions". Chemical Research in Toxicology (2): 494–502. doi:10.1021/tx700275p. PMID 18062674.

- ↑ Singani, A.A.S.; Ahmadi, P. (2012). "Manure Application and Cannabis Cultivation Influence on Speciation of Lead and Cadmium by Selective Sequential Extraction". Soil and Sediment Contamination (3): 305–21. doi:10.1080/15320383.2012.664186.

- ↑ McLaren, J.; Swift, W.; Dillon, P. et al. (2008). "Cannabis potency and contamination: A review of the literature". Addiction 103 (7): 1100–9. doi:10.1111/j.1360-0443.2008.02230.x. PMID 18494838.

- ↑ McPartland, J.M. (2002). "Chapter 30: Contaminants and Adulterants in Herbal Cannabis". In Grotenhermen, F.; Russo, E.. Cannabis and Cannabinoids: Pharmacology, Toxicology, and Therapeutic Potential. The Haworth Press. pp. 337–344. ISBN 9780789015082.

- ↑ McPartland, J.M., McKernan, K.J. (2017). "Contaminants of Concern in Cannabis: Microbes, Heavy Metals and Pesticides". In Chandra, S.; Lata, H.; ElSohly, M.. Cannabis sativa L. - Botany and Biotechnology. Springer. pp. 457–74. ISBN 9783319545646.

- ↑ Ruchlemer, R.; Amit-Kohn, M.; Raveh, D. et al. (2015). "Inhaled medicinal cannabis and the immunocompromised patient". Supportive Care in Cancer 23 (3): 819-22. doi:10.1007/s00520-014-2429-3. PMID 25216851.

- ↑ Thompson, G.R. 3rd; Tuscano, J.M.; Dennis, M. et al. (2017). "A microbiome assessment of medical marijuana". Clinical Microbiology and Infection 23 (4): 269-270. doi:10.1016/j.cmi.2016.12.001. PMID 27956269.

- ↑ California Bureau of Cannabis Control (October 2018). "California Code of Regulations, Title 15, Division 42, Bureau of Cannabis Control" (PDF). https://www.bcc.ca.gov/law_regs/cannabis_text.pdf. Retrieved 12 November 2018.

Notes

This presentation is faithful to the original, with only a few minor changes to presentation. Some grammar and punctuation was cleaned up to improve readability. In the original, references appear alphabetically; here they appear in order of appearance, by wiki design. In the original an image from ShutterStock was included; it was not added here because its not clear if the image can technically be included as Creative Commons content. Otherwise, in accordance with the NoDerivatives portion of the original license, nothing else has been changed.