Journal:Pathogens and molds affecting production and quality of Cannabis sativa L.

| Full article title | Pathogens and molds affecting production and quality of Cannabis sativa L. |

|---|---|

| Journal | Frontiers in Plant Science |

| Author(s) | Punja, Zamir K.; Collyer, Danielle; Scott, Cameron; Lung, Samantha; Holmes, Janesse; Sutton, Darren |

| Author affiliation(s) | Simon Fraser University |

| Primary contact | Email: punja at sfu dot ca |

| Editors | Smith, Donald L. |

| Year published | 2019 |

| Volume and issue | 10 |

| Article # | 1120 |

| DOI | 10.3389/fpls.2019.01120 |

| ISSN | 1664-462X |

| Distribution license | Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International |

| Website | https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpls.2019.01120/full |

| Download | https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpls.2019.01120/pdf (PDF) |

Abstract

Plant pathogens infecting marijuana (Cannabis sativa L.) plants reduce growth of the crop by affecting the roots, crown, and foliage. In addition, fungi (molds) that colonize the inflorescences (buds) during development or after harvest, and which colonize internal tissues as endophytes, can reduce product quality. The pathogens and molds that affect C. sativa grown hydroponically indoors (in environmentally controlled growth rooms and greenhouses) and field-grown plants were studied over multiple years of sampling. A polymerase chain reaction (PCR) assay using primers for the internal transcribed spacer region (ITS) of ribosomal DNA confirmed identity of the cultures. Root-infecting pathogens included those from the Fusarium genus (Fusarium oxysporum, Fusarium solani, and Fusarium brachygibbosum) and the Pythium genus (Pythium dissotocum, Pythium myriotylum, and Pythium aphanidermatum), which caused root browning, discoloration of the crown and pith tissues, stunting and yellowing of plants, and in some instances, plant death. On the foliage, powdery mildew, caused by Golovinomyces cichoracearum, was the major pathogen observed. On inflorescences, Penicillium bud rot (caused by Penicillium olsonii and Penicillium copticola), Botrytis bud rot (Botrytis cinerea), and Fusarium bud rot (F. solani, F. oxysporum) were present to varying extents. Endophytic fungi present in crown, stem, and petiole tissues included soil-colonizing and cellulolytic fungi, such as species of Chaetomium, Trametes, Trichoderma, Penicillium, and Fusarium. Analysis of air samples in indoor growing environments revealed that species of Penicillium, Cladosporium, Aspergillus, Fusarium, Beauveria, and Trichoderma were present. The latter two species were the result of the application of biocontrol products for control of insects and diseases, respectively. Fungal communities present in unpasteurized coconut (coco) fiber growing medium are potential sources of mold contamination on Cannabis plants. Swabs taken from greenhouse-grown and indoor buds pre- and post-harvest revealed the presence of Cladosporium and up to five species of Penicillium, as well as low levels of Alternaria species. Mechanical trimming of buds caused an increase in the frequency of Penicillium species, presumably by providing entry points through wounds or spreading endophytes from pith tissues. Aerial distribution of pathogen inoculum and mold spores and dissemination through vegetative propagation are important methods of spread, and entry through wound sites on roots, stems, and bud tissues facilitates pathogen establishment on Cannabis plants.

Keywords: diseases, plant pathogens, epidemiology, post-harvest molds, fungi, root infection, endophytes

Introduction

Cannabis sativa L., a member of the family Cannabaceae, is cultivated worldwide as hemp (for fiber, seed, and oil) and marijuana (referred to hereon as cannabis) for medicinal and psychotropic effects. The pathogens affecting production of hemp have been described and include fungal, bacterial, viral, and nematode species.[1][2] In contrast, the pathogens affecting Cannabis have not been extensively studied, and the different growing environments, cultivation methods, as well as differences among the strains or genetic selections of hemp and Cannabis can influence disease development. This requires that studies on the pathogens potentially affecting Cannabis plants be conducted so that methods to manage emerging diseases and molds can be developed. Cannabis plants are propagated from cuttings that are rooted and grown vegetatively, following which they are transferred to conditions of specific reduced lighting regimes (photoperiod) to induce flowering.[3] Flower buds are harvested, dried, and stored in vacuum-sealed bags or sealed plastic or glass containers prior to distribution. Fungal infection of roots can occur at any time during the production cycle, while colonization of flower buds generally occurs during the later stages of flower development and can be manifested as a pre-harvest or post-harvest bud rot. In addition, foliar pathogens may infect the plant at any stage during its production.

The objectives of this research were to determine the prevalence of root-infecting, foliar-infecting, and flower-infecting fungi affecting Cannabis plants grown in indoor environments, in greenhouses, and under field conditions to obtain a better understanding of the diseases affecting this plant. In addition, the incidence of molds in the growing environments, and on pre-harvest and post-harvest inflorescences, was assessed. Cultural methods for isolation, and morphological and molecular methods for identification, were used in this study. More than 22 different fungal and oomycete species and their associated effects on Cannabis plants grown indoors and outdoors are presented.

Materials and methods

Isolation of pathogens and molds from cannabis tissue

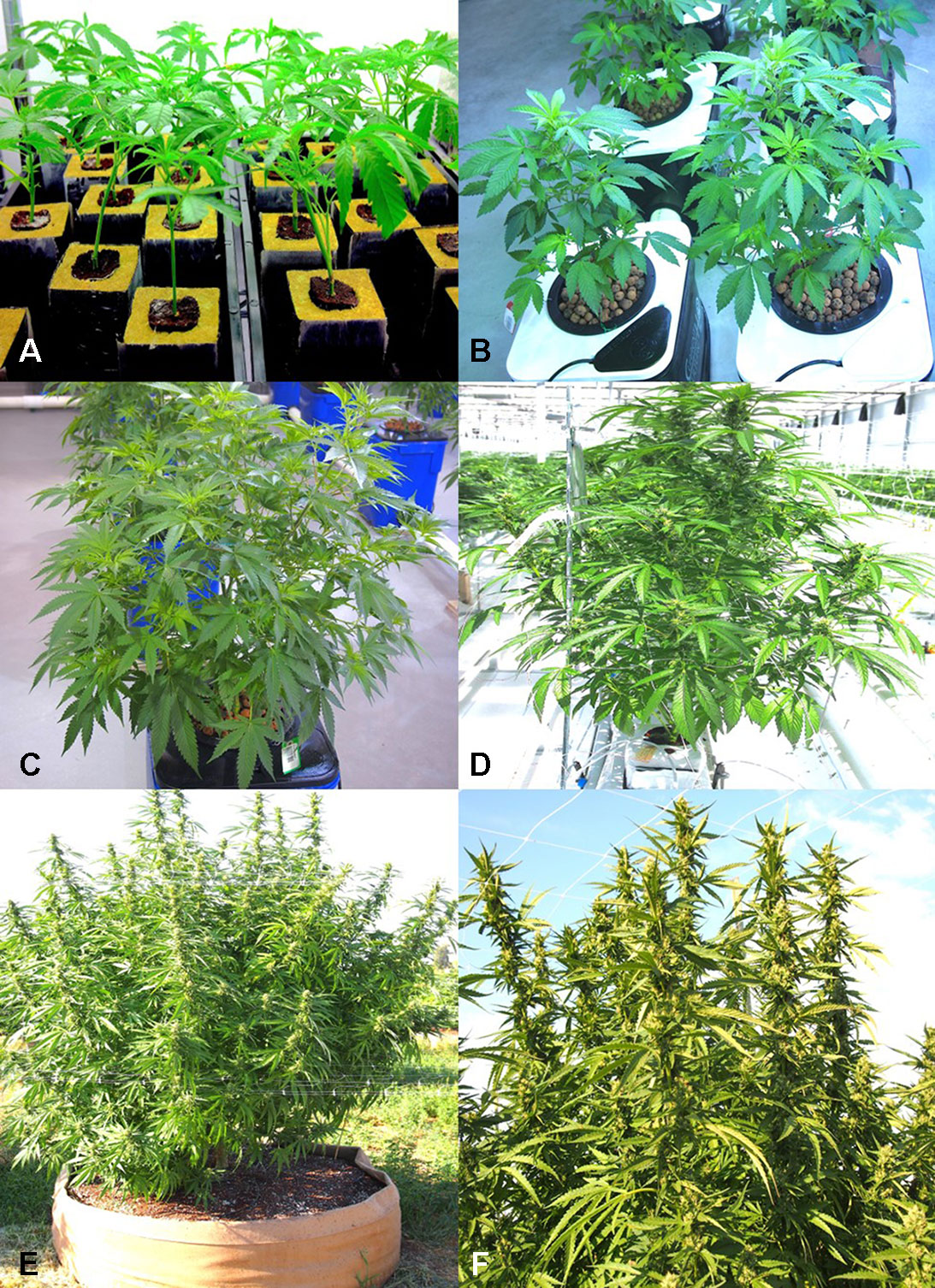

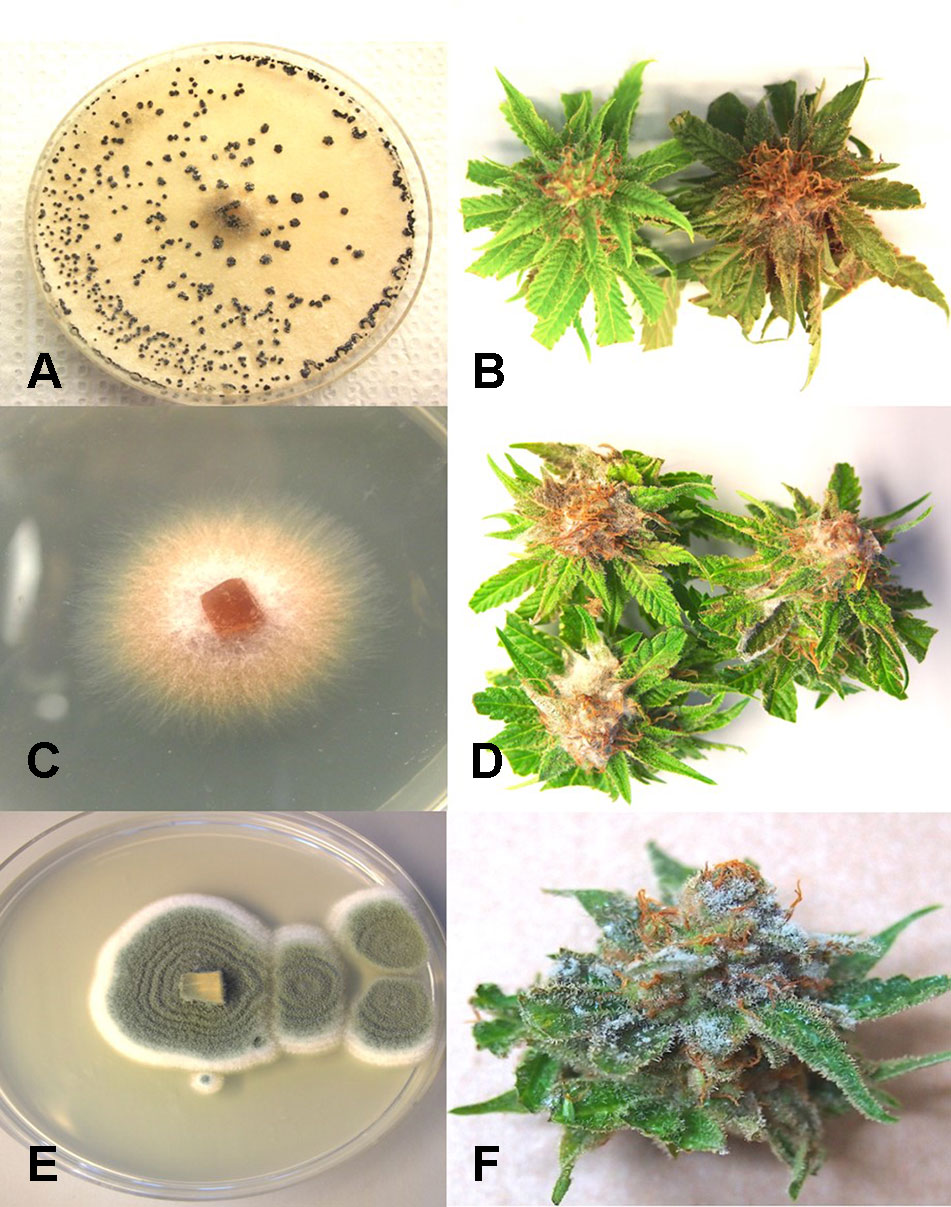

A range of tissue samples were obtained from Cannabis plants grown in indoor controlled environments (two locations) and greenhouse-grown plants (one location) of various Cannabis strains (e.g., Moby Dick, Hash Plant, Pink Kush, Pennywise, Girl Scout Cookies) under licensed commercial production, as well as from field-grown plants (one location) (Figure 1). They included roots, crown tissues, leaves, and flower buds. Samples either displayed symptoms of browning and were presumed to be infected by pathogens or were symptomless. Tissues were sampled at various times during growth of the plants, ranging from early stages of propagation (1–3 weeks old) (Figures 1A, B), to advanced vegetative growth (3–6 weeks of age) (Figures 1C, D), and then to plants that were in full flower (7–14 weeks of age) (Figures 1E, F). Samples were also obtained of harvested buds before and after they were dried, from indoor and field productions. These tissue samples were obtained over a duration of three years, from 2016 to 2018. They were taken at multiple times during the production cycle, and at varying time periods, depending on the pathogen of interest. Each sampling time had a minimum of five replicate samples. All plants were grown indoors and in greenhouses using either Rockwool blocks as a substrate or in coco fiber (coco coir) derived from different commercial suppliers. Plants were watered through an automated irrigation system with individual emitters for each plant. They were provided with the appropriate nutrient regimes and lighting conditions as required for commercial production.

|

A total of around 220 plants were sampled in the study. Among these, around 90 originated from the two indoor production facilities and 120 from the greenhouse facility, all located in British Columbia. In 2019, an additional five samples of diseased tissues were received from one production facility in Ontario, showing symptoms of root browning and stem discoloration, and five samples of bud tissues originated from a field production site in British Columbia in 2018. Plants with visible symptoms of disease were photographed.

Small tissue pieces of approximately 0.5 cm in length for roots or 0.2–0.4 cm2 for leaves or flower buds were surface-disinfected by dipping them in a 0.5% NaOCl solution for 30 seconds, followed by 20 seconds in 70% EtOH, rinsed thrice in sterile water, blotted on sterile paper towels, and plated onto Potato Dextrose Agar (PDA, Sigma Chemicals, St. Louis, MO) amended with 100 mg/L of streptomycin sulfate (PDA+S). Dishes containing the tissues were incubated under ambient laboratory conditions (temperature range of 21–24°C with 10–14-hours/day fluorescent lighting) for 5–10 days. Emerging colonies were recorded and transferred to fresh PDA+S dishes for subsequent identification to the genus level using morphological criteria, including colony color and size, as well as microscopic examination of spores. Species-level identification was done by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) using the primers ITS1F-ITS4 (ITS1-F 5’-CTTGGTCATTTAGAGGAAGTAA-3’ and ITS4 5’-TCCTCCGCTTATTGATATGC-3’). The resulting sequences were compared to the corresponding ITS1-5.8S-ITS2 sequences from the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) GenBank database to confirm species identity using only sequence identity values above 99%. These sequences have been deposited in GenBank. Pathogenicity tests were conducted for representative isolates (a minimum of two) of Fusarium oxysporum and Fusarium solani recovered from roots, as well as two isolates each of Botrytis cinerea and Penicillium olsonii recovered from flower buds, following the methods described by Punja and Rodriguez[5] and Punja.[6]

Scanning electron microscopy

Powdery mildew infection of leaves, and infection of buds by P. olsonii and F. oxysporum following artificial inoculation with spores, as well as stem segments showing pith tissues, was prepared for scanning electron microscopy (SEM) as follows. Tissue segments of approximately 0.5 cm2 were adhered to a stub using a graphite-water colloidal mixture (G303 Colloidal Graphite, Agar Scientific, UK) and Tissue-Tek (O.C.T. Compound, Sakura Finetek, NL). The sample was submerged in a nitrogen slush for 10–20 seconds to rapidly freeze it. After freezing, the sample was placed in the preparation chamber of a Quorum PP3010T cryosystem attached to a FEI Helios NanoLab 650 scanning electron microscope (Dept. of Chemistry, 4D Labs, Simon Fraser University). The frozen sample was sublimed for five minutes at −80°C, after which a thin layer of platinum (10-nm thickness) was sputter-coated onto the sample for 30 seconds at a current of 10 mA. The sample was moved into the SEM chamber, and the electron beam was set to a current of 50 pA at 3 kV. Images were captured at a working distance of 4 mm, at a scanning resolution of 3072 x 2207 collected over 128 low-dose scanning passes with drift correction.

Mold sampling in different growing environments

To assess the potential for airborne dispersal of mold and pathogen spores within different growing environments, 9-cm diameter petri dishes containing PDA+S were placed with the lids removed on benches in areas between rows of plants, at approximately one-meter intervals, in both indoor growing environments and in the greenhouse during 2018. Field sampling was not conducted. The dishes were left for 60 minutes and then lids replaced and brought back to the laboratory. All air sampling was done during the period of 11:00 to 13:00 hours. A minimum of 12 replicate dishes was included at each sampling location. Control dishes were placed in similar locations with the petri dish lids left on. Fungal colonies that developed after five to seven days were counted, and representative ones were subcultured for identification. The sampling was repeated in two different indoor environments at various time periods (March–September) during 2018 and repeated three times within one greenhouse facility. In the indoor facilities, the sampling was conducted weekly in the same growing room over six sequential weeks (June–July 2018) to assess changes in the mold populations over time. In the greenhouse facility, the sampling was repeated weekly over four weeks (June–September 2018). The sampling time was kept the same in all studies. Fungal colonies were identified to genus level using morphological criteria. Specific colonies were subcultured onto fresh medium and used for DNA extraction. Molecular identification to genus and species level was conducted as described previously. Mean colony-forming units of each fungal genus per petri dish was determined, and standard error of the means was calculated from the replications and repetitions.

Isolation of fungi from coco fiber substrates

Samples consisting of approximately 5–10 g of coco fiber (coco coir) substrate used for growing plants were obtained at multiple times during the production cycle in five indoor and greenhouse facilities to assess the diversity and total populations of fungi present. In addition, samples were taken from previously unopened and unused bags. The brand names included Mo’KoKo, Royal Gold (Humboldt County, CA), Canna Coco (Toronto, Canada), Forteco, and Rio (Irving, TX). A subsample of 0.5 g was suspended in 10 ml of sterile distilled water and vortexed for 20 seconds. A 1-ml suspension was transferred to 9 ml of water, shaken, and a further dilution was made in 9 ml of water. Aliquots (0.5 ml) of each suspension were streaked onto two replicate PDA+S plates and repeated three times for each sample. The plates were incubated for 5–7 days under ambient laboratory conditions and then examined for diversity and numbers of microbes present. Fungal colonies were identified to genus level where possible using morphological criteria. Specific colonies were subcultured onto fresh medium and used for DNA extraction and molecular identification as described previously.

Isolation of fungi from internal tissues of plants

The presence of naturally occurring endophytic fungi within stem tissues of the “Moby Dick” strain of C. sativa was determined through dissection of a mature indoor-grown plant grown using coco fiber (Canna Coco) as a substrate. Plants were provided with 24 hours of light through an Agrobrite T5H0 Fixture (Hydrofarm Inc., Petaluma, CA) containing four 6,400K spectrum bulbs, with a light intensity of 9,400 lumens to maintain vegetative growth. The temperature range was 23–28°C. Fertilization was achieved through a mixture of Advanced Nutrients: pH Perfect Sensi Grow A and B and CALiMAGic by General Hydroponics (Sebastopol, CA), each at a rate of 1 ml/L (pH 5.8). Plants were watered approximately once a day until runoff. The main stem of the plant was sectioned into 5-cm long segments, beginning at the crown and proceeding to the top of the plant through two lateral branches on each side, a distance of around 75 cm. The stem pieces were surface-sterilized in a 10% bleach solution (Javex, containing 6.25% NaOCl) for 20 seconds followed by 70% EtOH for 20 seconds and rinsed with sterile distilled water for one minute. The segments were transferred to a sterile petri dish, where they were cut lengthwise with a scalpel and small tissue pieces, measuring approximately 0.5 cm2 were cut to represent the cortex/vascular tissues and the pith, which were plated separately. Thinner stem pieces included just the vascular and cortical tissues without the pith. A total of four tissue pieces of each type were placed onto each of two petri dishes containing PDA+S and incubated under ambient laboratory conditions for one week before microbial presence was assessed.

In the next series of experiments, three additional strains of C. sativa were used to establish the extent of internal colonization by microbes. These strains were “Pennywise,” “Space Queen,” and “Cheesequake.” Tissue segments representing stem pieces, petioles, and nodal segments (approx. 0.5 mm in length) were excised from plants grown as described above and surface-sterilized in a 10% bleach solution for one minute, followed by 70% EtOH for 30 seconds and then rinsed in sterile distilled water for one minute and plated onto PDA+S dishes. The number of fungal colonies emerging from the tissue pieces was recorded, and the genera were identified by morphological examination of the colony or spore type. Molecular confirmation was conducted as described previously for selected cultures. Bacteria and yeasts were excluded from the total counts of microbial presence. The experiment was conducted twice using different plants of the same strains.

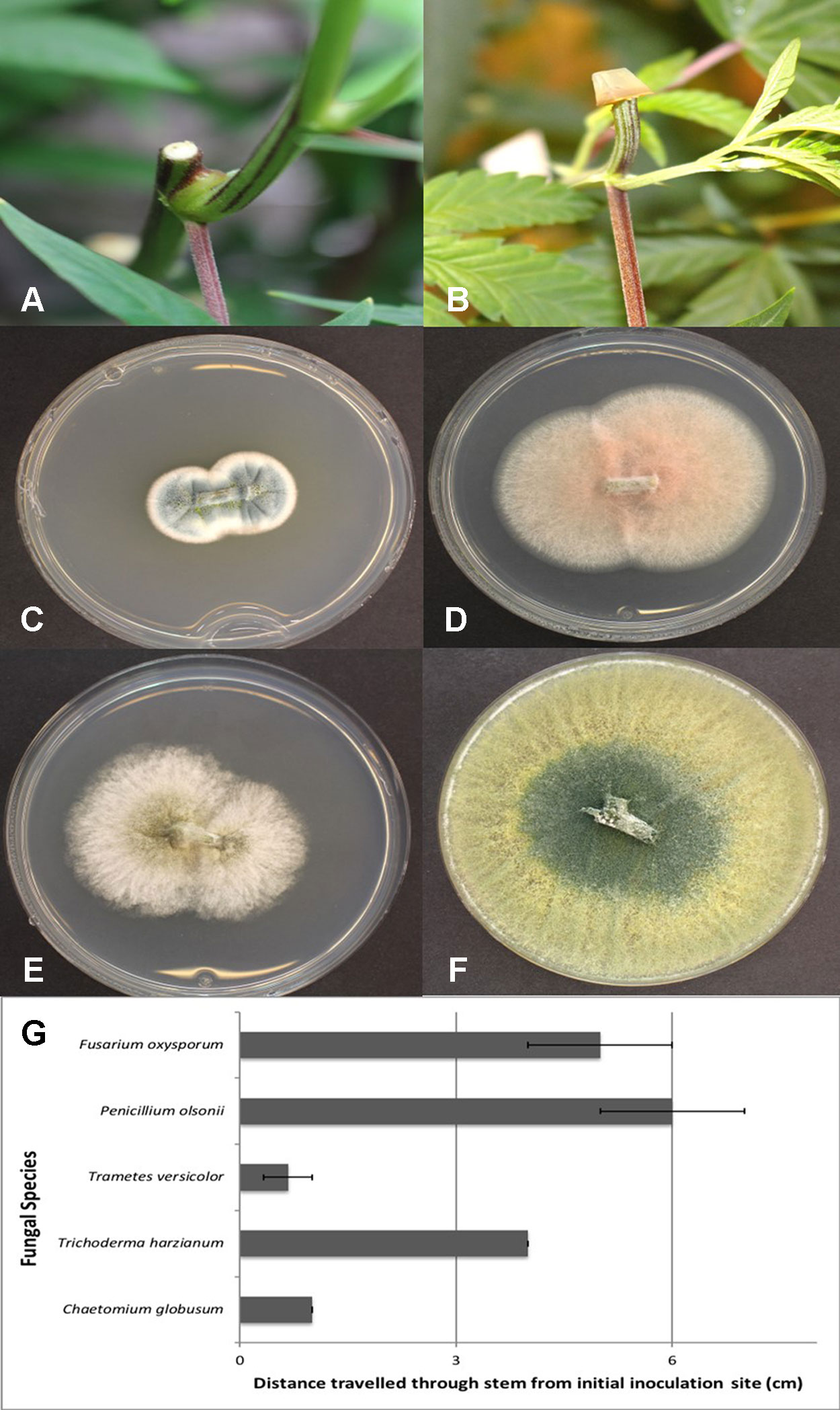

Endophytic colonization of stem tissues

Plants of C. sativa L. were grown in coco fiber as a substrate under a 200-watt Sunblaster CFL light and fertilized as described previously. The uppermost 2 cm growing region of the plant (at 65-cm distance from the crown) were cut; 1-cm long segments were removed from just below the cut end and then surface-sterilized in 10% bleach for one minute, followed by 70% EtOH for 30 seconds and then rinsed in sterile distilled water for one minute. Pieces measuring 0.5 cm in length were placed on PDA+S (300 mg/L). This procedure was conducted to check for presence of background endophytes. The wounded exposed stem surfaces on the plant (with eight replicates) were then inoculated by placing a mycelial plug (approx. 1 cm2) on the surface of the cut stem (mycelial side down) and left in place for seven days. Controls received a PDA plug or were left uninoculated. Cultures of the fungi used were grown on PDA+S for two weeks before being used. The fungi tested were recovered from internal tissues of Cannabis plants as described in the preceding section. They were identified as Chaetomium globosum, F. oxysporum, P. olsonii, Trametes (Polyporus) versicolor, and Trichoderma harzianum. After seven days, the plug was removed, and stem segments were excised at distances of 1, 3, and 6 cm below the initial cut site that was inoculated with the plug. These segments were surface-sterilized as described previously and plated on PDA+S (300 mg/L). The colonization of each stem segment by each of the respective fungi at each distance was rated after seven days. The experiment was conducted twice. The data was expressed as means +/− standard deviations.

Mold sampling on bud tissues

Mold assessments on pre-harvest and post-harvest flower buds were made using a cotton swab procedure during 2017–2018. Sterile cotton swabs were gently wiped across the surface of buds on plants either prior to harvest or following harvest, as well as at various stages of a mechanized trim operation that removed bract and leaf tissues surrounding the inflorescence. This was repeated from replicate samples at multiple time periods in two different facilities. The swabs were streaked across a PDA+S dish, which was then brought back to the laboratory and incubated under ambient conditions as described previously. The swab method was also used to assess the presence of fungi on freshly cut and healed stems on Cannabis plants following regular pruning of shoots in both an indoor and greenhouse growing facility. For harvested dried buds, small segments of approximately 2 mm were taken from replicate samples (total of 50) at multiple time periods (up to eight) and were placed directly onto PDA+S dishes, or following a 20 second dip in 70% EtOH. Following incubation for seven days under ambient laboratory conditions, enumeration of fungal colonies on the dishes (bacterial colonies were excluded) was conducted; representative morphologically unique colonies were subcultured onto fresh PDA+S dishes and used for DNA extraction and PCR-ITS identification to species level as described previously.

Results

Isolation of pathogens and molds from Cannabis tissues

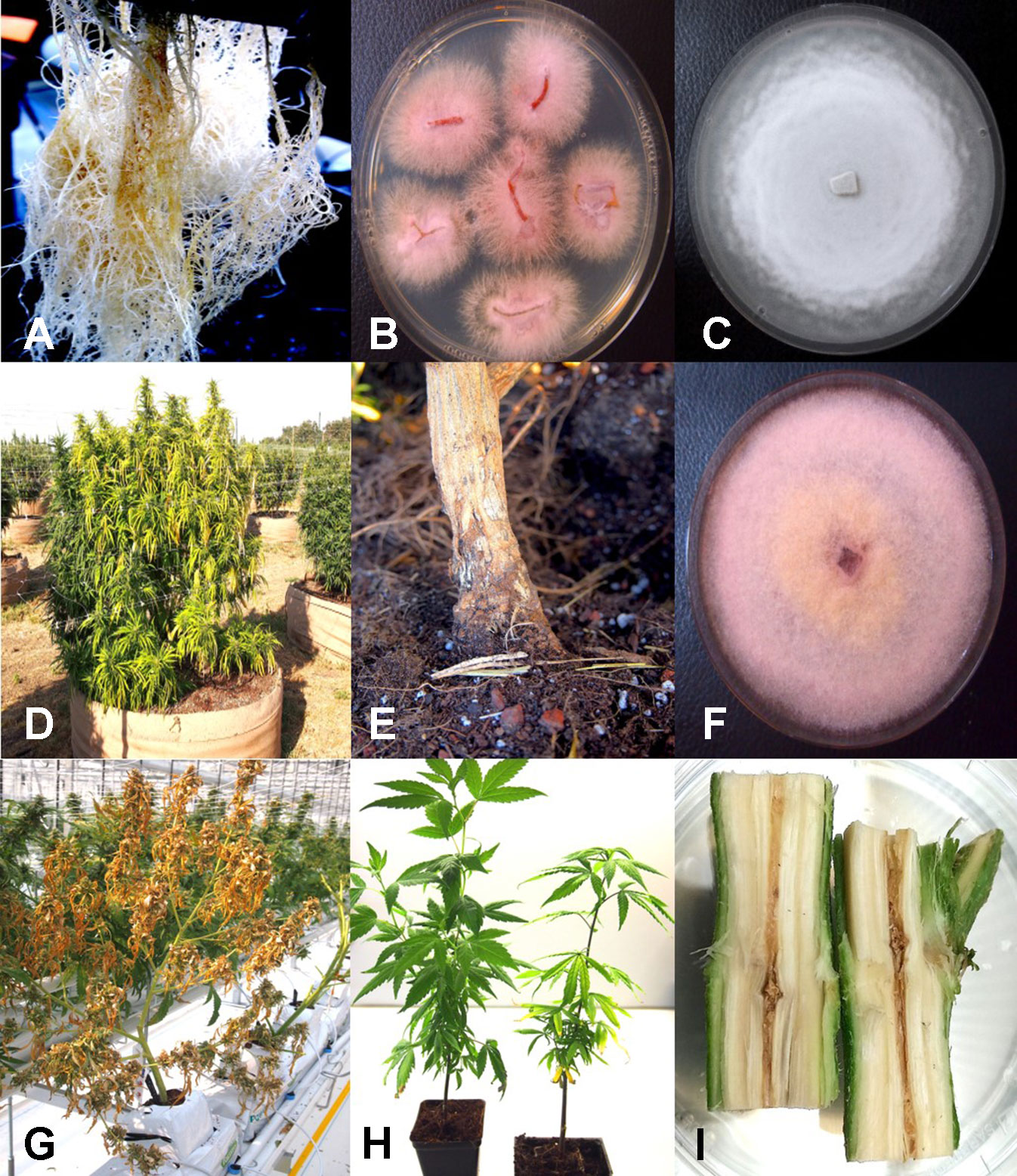

From Cannabis plants grown in an indoor hydroponic production system in which brown roots were visible (Figure 2A) and from a greenhouse production system in which coco fiber was used as a growing substrate and with visible brown roots, samples were collected and used for isolation. Colonies of F. oxysporum (Figure 2B) and Pythium species that included Pythium dissotocum, Pythium myriotylum, Pythium aphanidermatum, Pythium ultimum, and Pythium catenulatum (Figure 2C) were recovered and identified based on ITS 1-ITS2 rDNA sequence comparisons to GenBank. Additional species of Fusarium that have been recovered from diseased Cannabis root and crown tissues include F. solani and Fusarium proliferatum. From tissue samples originating from Ontario, F. oxysporum, P. myriotylum, and P. dissotocum were recovered from symptomatic crown and root tissues. From field-grown plants with symptoms of yellowing foliage (Figure 2D) and sunken lesions present on the crown of affected plants (Figure 2E), F. oxysporum, P. aphanidermatum, and Fusarium brachygibbosum (Figure 2F) were isolated and identified. From a greenhouse-grown plant close to harvest and displaying symptoms of browning and plant collapse (Figure 2G), P. aphanidermatum was isolated. The pathogenicity of two isolates of F. oxysporum and F. solani originating from Cannabis plants was confirmed by re-inoculation of rooted Cannabis cuttings. The results from inoculation with F. oxysporum are shown in Figure 2H, in which symptoms of stunting and yellowing were apparent after 3–4 weeks. The pith tissues of these plants exhibited browning (Figure 2I), and the pathogen was reisolated. For the F. solani isolates tested, similar symptoms were observed, except that root and pith browning were more extensive. Therefore, individual root pathogens as well as combinations of pathogens may be recovered from symptomatic Cannabis plants grown indoors and under field conditions.

|

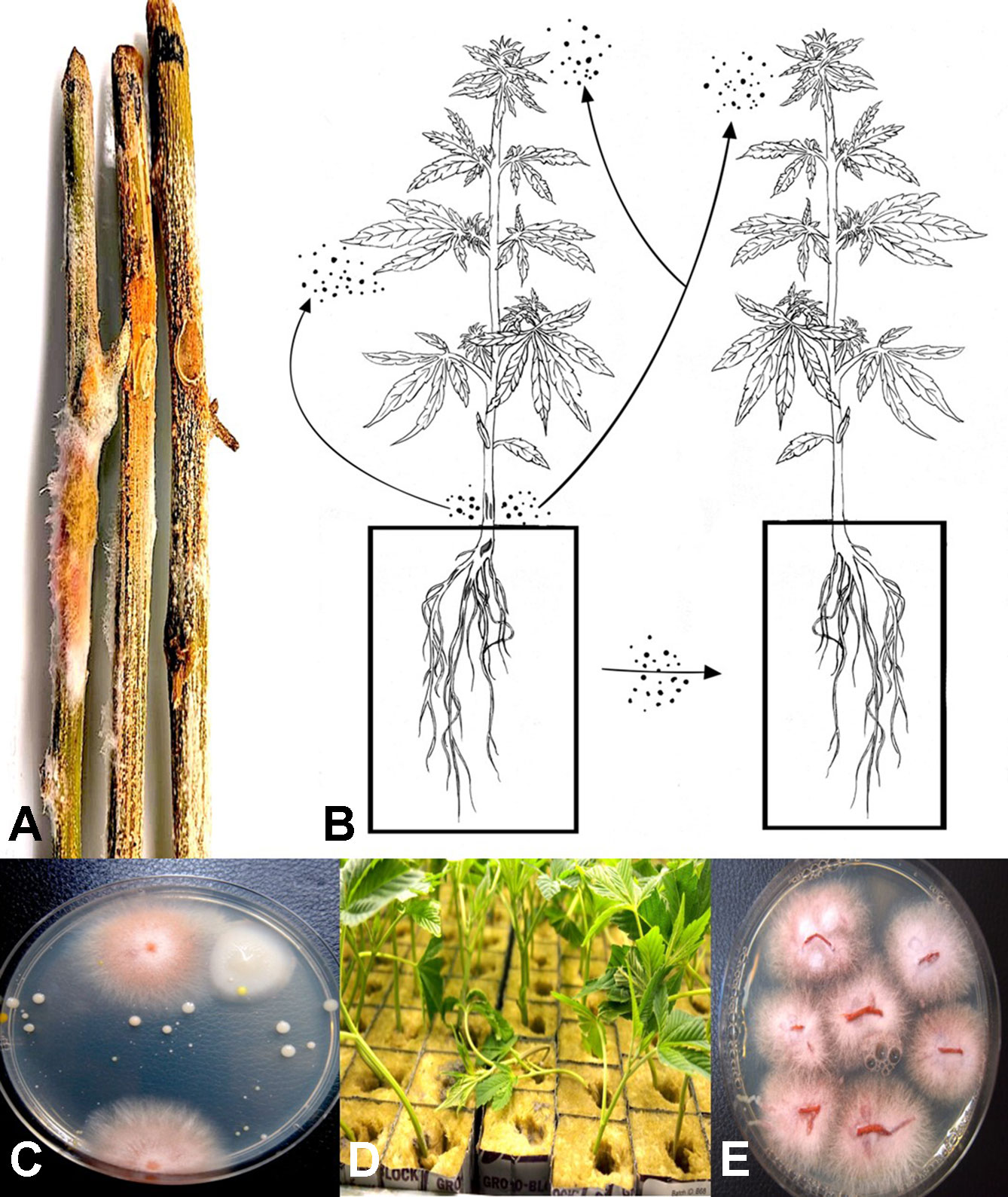

The potential for production of spores of Fusarium species on stem tissues of Cannabis plants was demonstrated by inoculating mycelial plugs onto harvested stem segments and incubating them under high humidity conditions for five days. Prolific spore production, which can result in spread of inoculum into the air, can potentially result in foliar or flower bud infection on the same or adjacent plants (Figure 3A). In addition, spores of F. oxysporum may be spread though water or hydroponic nutrient solution as demonstrated by recovery on PDA (Figure 3B), and if recirculated without treatment to destroy pathogen spores (Figure 3C), it can introduce inoculum into propagation rooms where cuttings are being rooted, causing mortality (Figure 3D) and crown and root infection from which F. oxysporum was readily isolated (Figure 3E). Therefore, F. oxysporum is capable of infecting at multiple locations within a production facility.

|

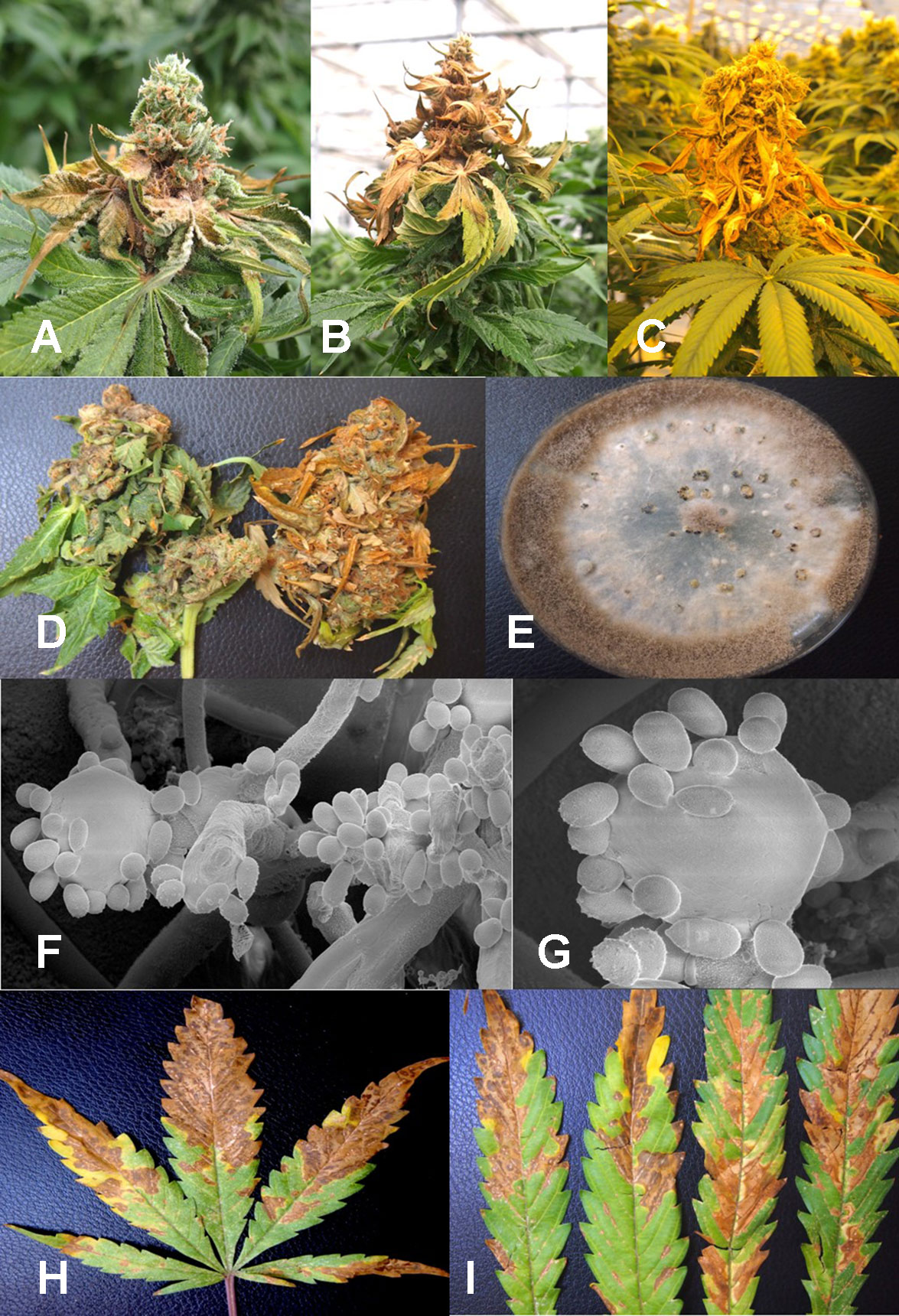

From flower buds with symptoms of brown discoloration, blighting of bracts and leaves and decay of the tissues (Figures 4A–C), grayish-brown mycelium was observed when the tissues were incubated in a plastic bag for 48 hours (Figure 4D), and colonies recovered with gray sporulation were identified as B. cinerea causing bud rot (Figure 4E). Spores were formed on conidiophores and borne in clusters (Figures 4F, G). In severe cases of disease incidence (up to 50% of plants affected), leaves on Cannabis plants with bud rot also displayed leaf lesions (Figures 4H, I). The lesions developed as small circular spots which enlarged to coalesce into necrotic areas that were sometimes surrounded by yellow margins and in many cases delimited by the leaf veins. Surface-sterilized tissue pieces plated onto PDA+S yielded colonies similar to those shown in Figure 4E. These foliar infections due to B. cinerea have not been previously reported on Cannabis plants and appear to occur only under conditions of high inoculum levels and on plants approaching harvest.

|

From samples of 50 harvested flower buds that were fresh or had previously been dried, three fungal species were identified: B. cinerea (Figure 5A), F. oxysporum (Figure 5C), and P. olsonii (Figure 5E). The overall frequencies of recovery were 2, 2.7, and 7.4%, respectively. When these fungi were inoculated onto fresh flower buds and incubated under conditions of high humidity, all of them were capable of causing browning of the tissues and decay to varying extents (Figures 5B, D, F).

|

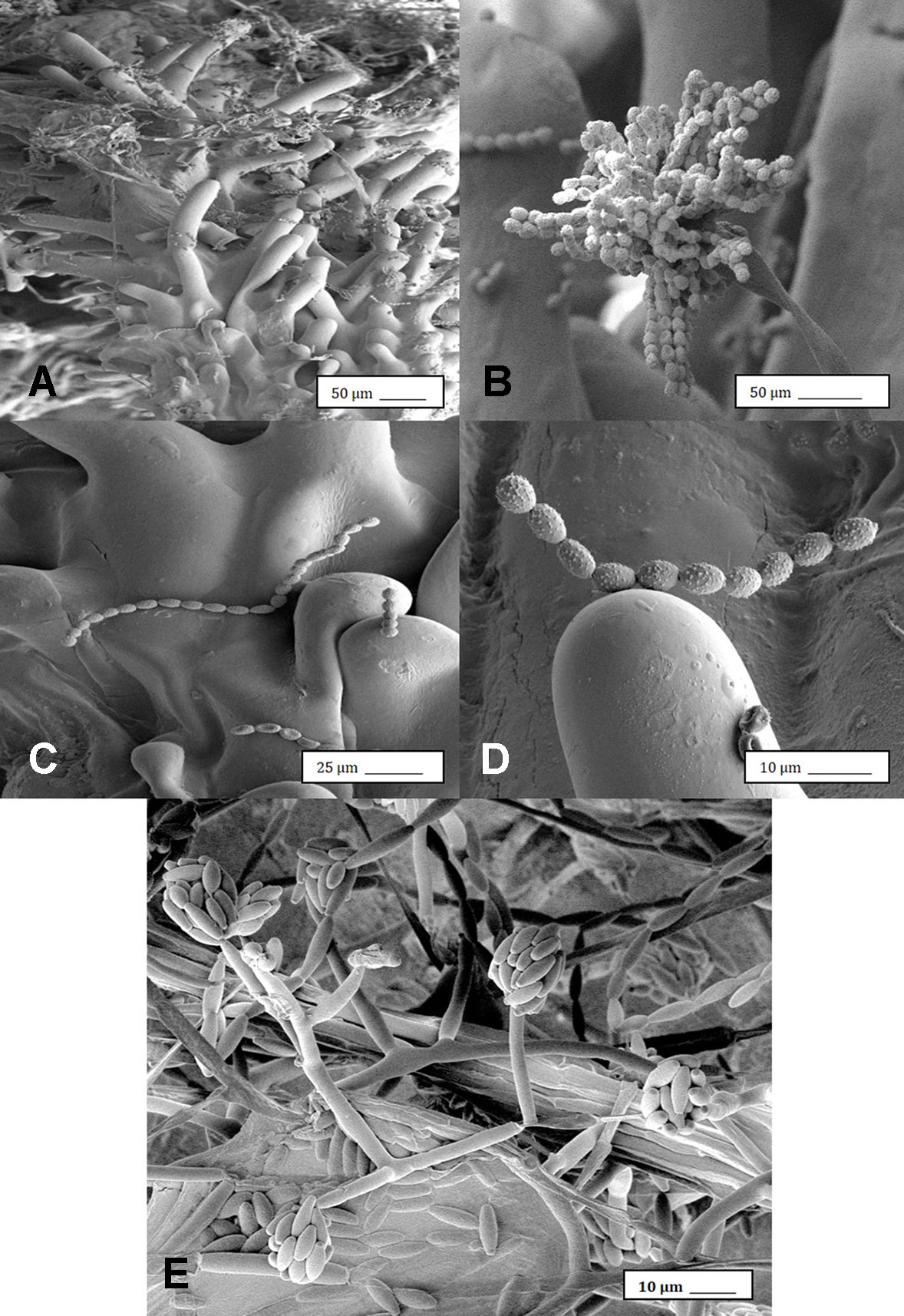

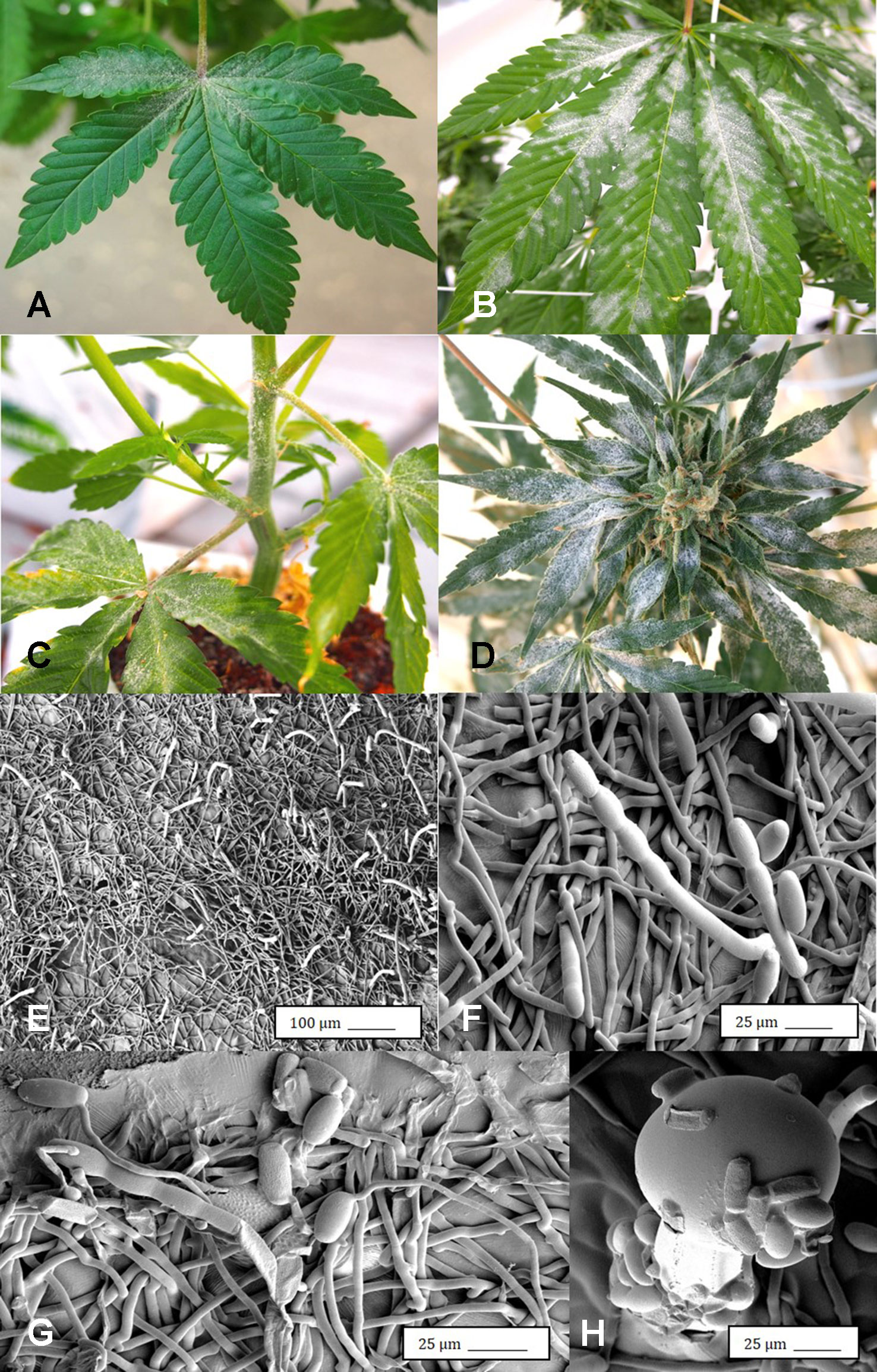

Scanning electron microscopy

Under the scanning electron microscope, Cannabis flower buds that had been inoculated with a spore suspension of P. olsonii showed the presence of abundant mycelial growth and sporulation on the stigmatic surface (Figures 6A, B), and chains of spores were formed that were stuck to the stigmatic hairs (papillae) (Figures 6C, D). Similarly, flower buds inoculated with a spore suspension of F. oxysporum also showed abundant pathogen sporulation (Figure 6E). Leaves with natural infection by powdery mildew initially showed white mycelial growth, followed by abundant sporulation of the pathogen, which caused the leaves to develop a white powdery appearance (Figures 7A, B). In addition, infection was observed on stems (Figure 7C) and on inflorescences (Figure 7D). Under the scanning electron microscope, abundant mycelial growth on the leaf surface was accompanied by spores that were produced on conidiophores and were borne in chains (Figures 7E–G). Spores were also observed to germinate on the leaf surface (Figure 7H), and they were found adhered to the surface of glandular trichomes (Figure 7I). The pathogen was identified by ITS1-ITS2 rDNA sequence comparisons available in GenBank as Golovinomyces cichoracearum. However, isolates from Cannabis could not be distinguished using the ITS region from Golovinomyces ambrosiae reported to infect sunflower and giant ragweed and Golovinomyces spadiceus from dahlia.[4] Therefore, the species of powdery mildew affecting Cannabis is provisionally named G. cichoracearum sensu lato and will require additional sequence comparisons of gene regions other than the ITS to confirm the species identity.

|

|

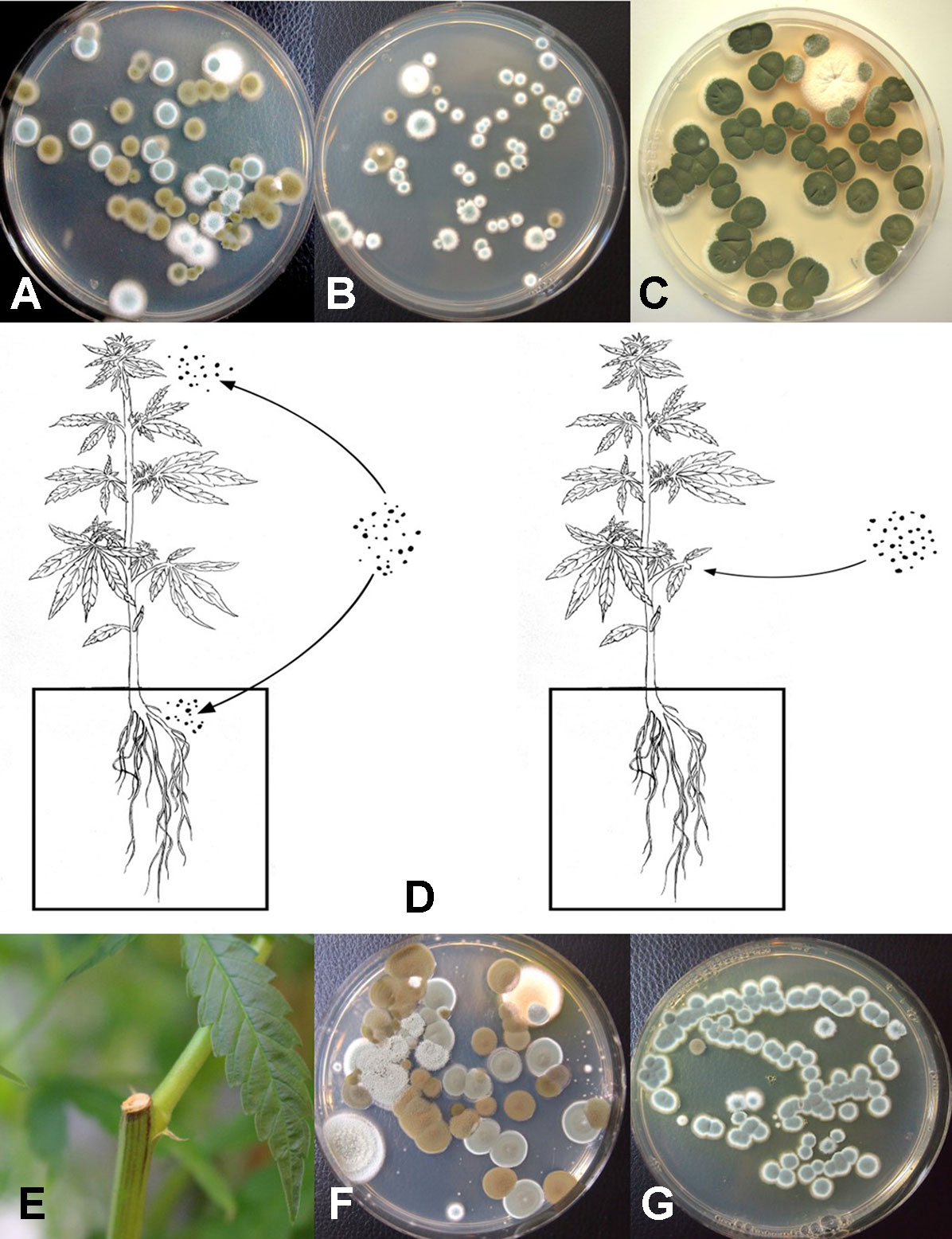

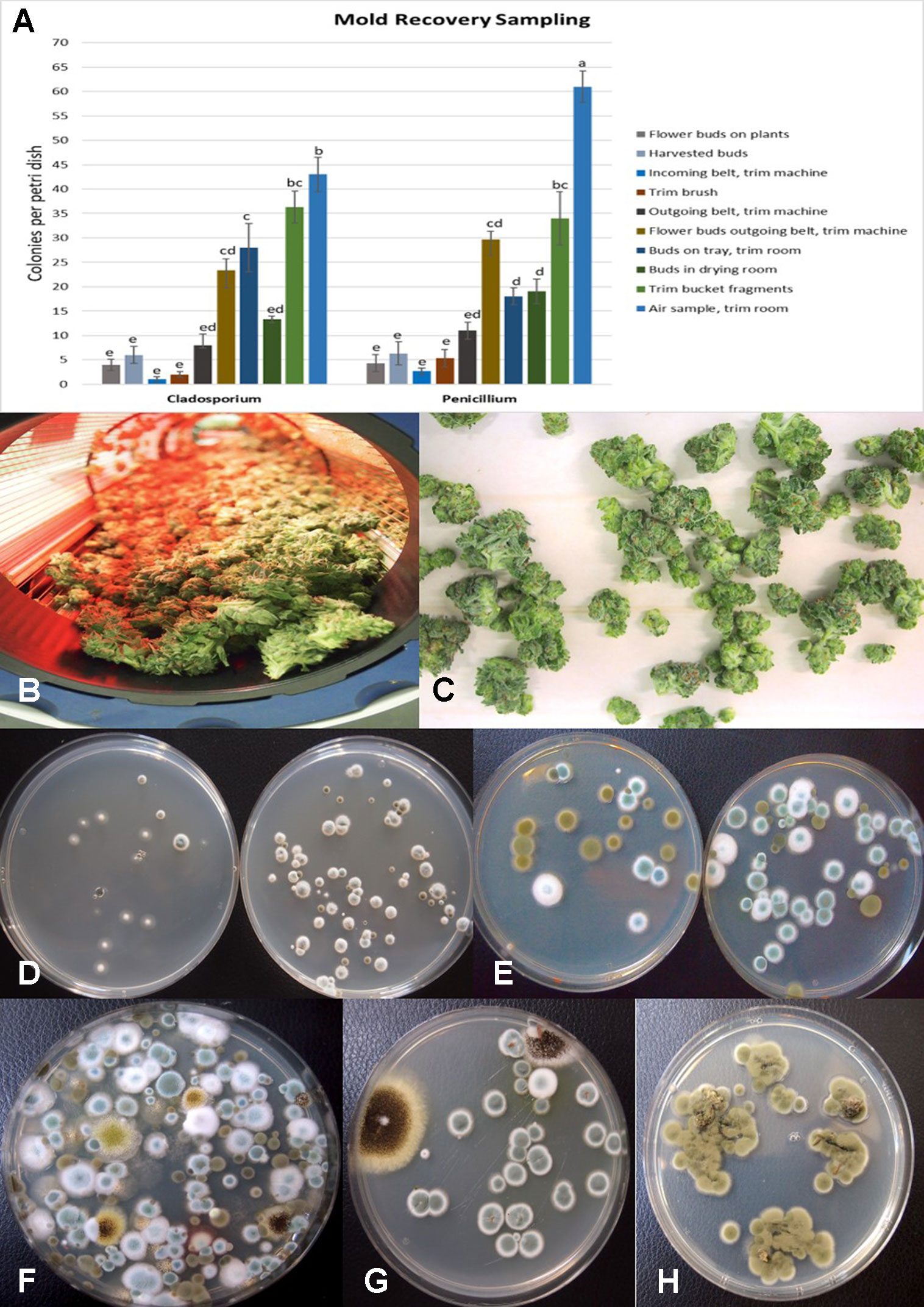

Mold sampling in different growing environments

The placement of petri dishes containing potato dextrose agar plus 100 mg/L of streptomycin sulfate with the lids removed for periods of up to one hour in greenhouses and indoor controlled environment growing facilities of Cannabis provided an indication of the types of molds that were present within each growing environment. Under greenhouse conditions, the principal mold genera recovered were Cladosporium and Penicillium (Figure 8A). In indoor growing environments, Penicillium species were most prevalent (Figure 8B). The potential sources of these fungi are from decaying plant material, growing substrates used such as coco fiber, as well as indoor structures and equipment. By comparison, petri dishes placed in greenhouse environments showed a high level of Cladosporium (Figure 8C). Once airborne, the spores can land on leaves, flower buds, cut exposed stems, or growing substrates such as Rockwool and colonize the substrate (Figure 8D). The cut surfaces of stems that had been pruned (Figure 8E) and were forming wound response tissue yielded both Cladosporium and Penicillium species from a greenhouse environment (Figure 8F), similar to those found in air samples (Figure 8A). On indoor plants where cut stems were sampled, Penicillium species, as well as F. oxysporum, were recovered (Figure 8G).

|

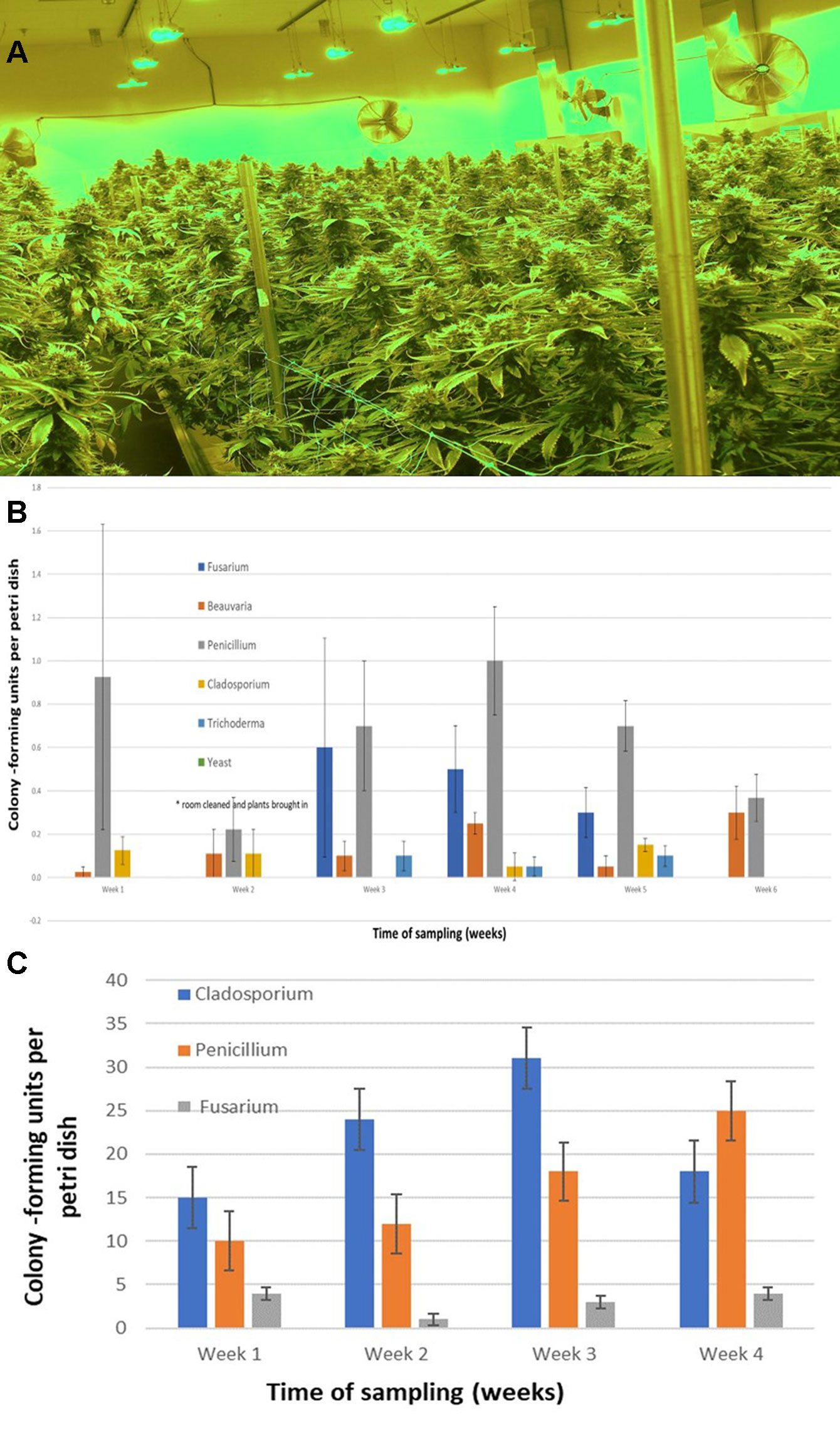

The air sampling procedure using exposed petri dishes was conducted over a six-week period in an indoor controlled environment growing facility (Figures 9A, B) as well as over a four-week period in a greenhouse facility (Figure 9C). The results showed several relevant findings:

- 1. Following a thorough cleaning of the indoor facility, which showed high levels of Penicillium species (in week one), mold levels were initially very low in week two when plants were introduced (with Beauveria bassiana, P. olsonii, and Cladosporium westerdijkieae present at low background levels).

- 2. Fusarium oxysporum and Penicillium population levels increased following the introduction of Cannabis plants in week three, and T. harzianum was detected (Figure 9B).

- 3. The population levels of the fungal species were variable in weeks four through six, with Penicillium representing the most frequently detected mold. The presence of B. bassiana and T. harzianum, both of which are registered as biological control agents (BotaniGard and RootShield, respectively) and had been applied within the facility for control of thrips and Fusarium root rot in the week preceding sampling, was interesting to see as a component of the air-borne mold population.

- 4. In the final week of sampling (week six), the predominant fungi found were Beauveria and Penicillium, and no Fusarium was detected. In the greenhouse facility, a similar air sampling study conducted over a four-week period showed that the predominant fungi found were Cladosporium, Penicillium, and low levels of Fusarium (Figure 9C); however, the total colony-forming units were higher in the greenhouse facility (maximum of 30 cfu/petri dish) compared to those found in the indoor growing environment (maximum of 1 cfu/petri dish).

|

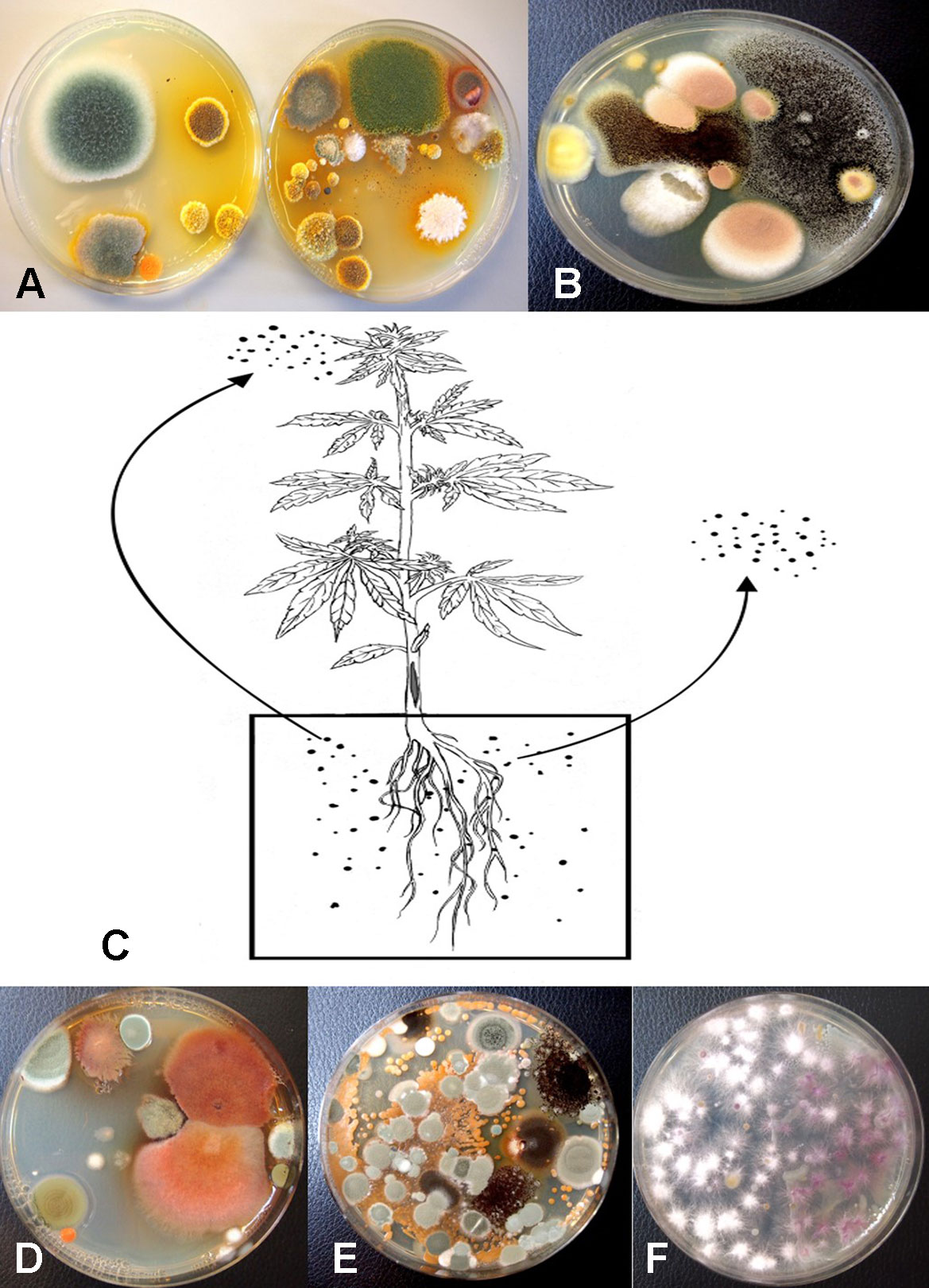

Isolation of fungi from coco fiber substrates

Following serial dilution and plating of samples of coco fiber onto PDA+S Petri dishes, a large and diverse number of fungi, yeast, and bacteria were observed growing after five days of incubation (Figures 10A, B). The range of fungi identified included P. olsonii and Penicillium chrysogenum, Aspergillus niger, Aspergillus ochraceus, Aspergillus terreus, Rhizopus stolonifer, T. harzianum, B. bassiana, F. oxysporum, and other unidentified species. All of these, especially A. niger and Penicillium species, were present in unopened bags originating from different sources. The potential for spread of spores of these fungi as air-borne propagules during cultivation of plants to leaves and flower buds of Cannabis plants is possible (Figure 10C). Not all coco fiber substrates tested were contaminated to a similar level with these fungi, and some products (which had been sterilized) were mostly found to contain only Penicillium species (data not shown). The extent to which coco fiber substrates harbored total microbial populations increased over time of usage for plant growth, and at the end of the cropping cycle, the populations of bacteria and yeast were considerably higher than fungal populations (Figure 10D compared to Figure 10E). In some samples, F. oxysporum was the most predominant microbe in the end-of-cycle coco fiber samples (Figure 10F).

|

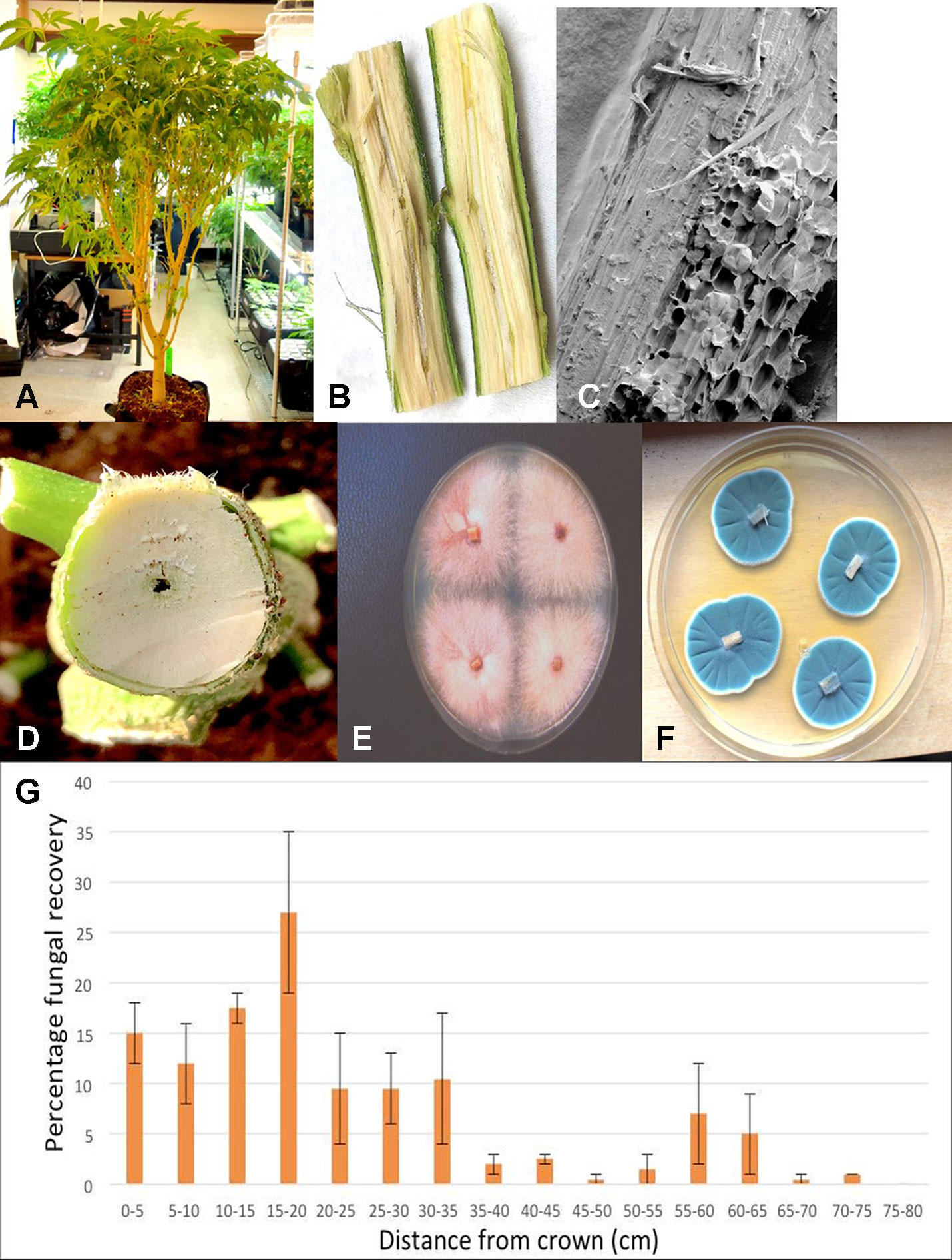

Isolation of fungi from internal tissues of plants

Plants grown in coco fiber substrate and sampled for presence of fungi in the pith and cortical/vascular tissues, as well as petiole and nodal segments, showed the presence of many fungal species, including C. globosum, T. (Polyporus) versicolor, T. harzianum (Figure 14A), F. oxysporum (Figure 11F), and P. chrysogenum (Figure 11G). In addition, a low frequency of Lecanicillium lanosoniveum and a Simplicillium sp. were recovered from nodal segments (Figure 14A). The overall frequency of isolation of these endophytic fungi was greater in tissues sampled near the crown of the plant and was reduced progressing upward to a distance of 30–35 cm; following that, the incidence of recovery of these fungi was sporadic (Figure 11H). From surface-sterilized stem, petiole, and nodal segments, recovery of Penicillium species (identified as P. olsonii and Penicillium griseofulvum) was high and was seen to be emerging from the cut ends (Figure 14B), and spore production was observed internally within pith tissues and adjacent to pith cells (Figures 14C, D).

|

Endophytic colonization of stem tissues

Mycelial plugs of five of the endophytic fungi recovered from Cannabis stem tissues, when placed on freshly exposed stem surfaces (Figures 12A, B), demonstrated the ability of these fungi to colonize internally for distances of up to 6 cm within seven days. The growth of F. oxysporum and P. olsonii was the greatest, followed by T. harzianum, and then C. globosum and P. versicolor (Figure 12G). Since the tissues were surface-sterilized before plating, the fungi recovered (Figures 12C–F) originated from inside the stem tissues, while control tissues yielded no fungi except for occasional (less than 5%) contamination by Penicillium species.

|

Mold sampling on bud tissues

The results from mold sampling on greenhouse-grown Cannabis buds of pre- and post-harvests are shown in Figure 13. A low incidence (5–10 colony-forming units [cfu] per petri dish) of Cladosporium and Penicillium were found on these buds (Figure 13A). Following a mechanized trim operation (Figures 13B, C), the frequency of mold colonies increased to 25-30 cfu. The fragments of leaves and bracts that were removed from the buds after the trim and collected in a trim bucket were found to have a high mold count of up to 38 cfu present (Figure 13A). There was a large increase in the recovery of mold colonies, particularly those of Penicillium, from bud tissues before and after the trim operations (see Figure 13A, “harvested buds” versus “buds on tray”). A comparison of the colonies developing on PDA+S before and after the bud trimming operation (right petri dish in both photos) in two growing facilities is shown in Figures 13D and 13E. Petri dishes left exposed in the room where the trimming operation was being conducted showed a diverse population of mold colonies in the air, representing mostly Penicillium species, though a few Aspergillus colonies were also recovered (Figure 13F). Swabs of buds in the drying room showed the presence of Penicillium, Aspergillus, and Cladosporium on tissues from two different production facilities (Figure 13G). Selected colonies were transferred to fresh PDA+S dishes for subsequent molecular confirmation of species identification using ITS1-ITS2. In sampling conducted of field-grown, harvested, and dried buds of Cannabis, the primary mold found to be present was C. westerdijkieae (75% frequency of total fungi isolated) (Figure 13H), and a low population of Alternaria alternata was also present (20% frequency), as well as some colonies of P. olsonii (5% frequency).

|

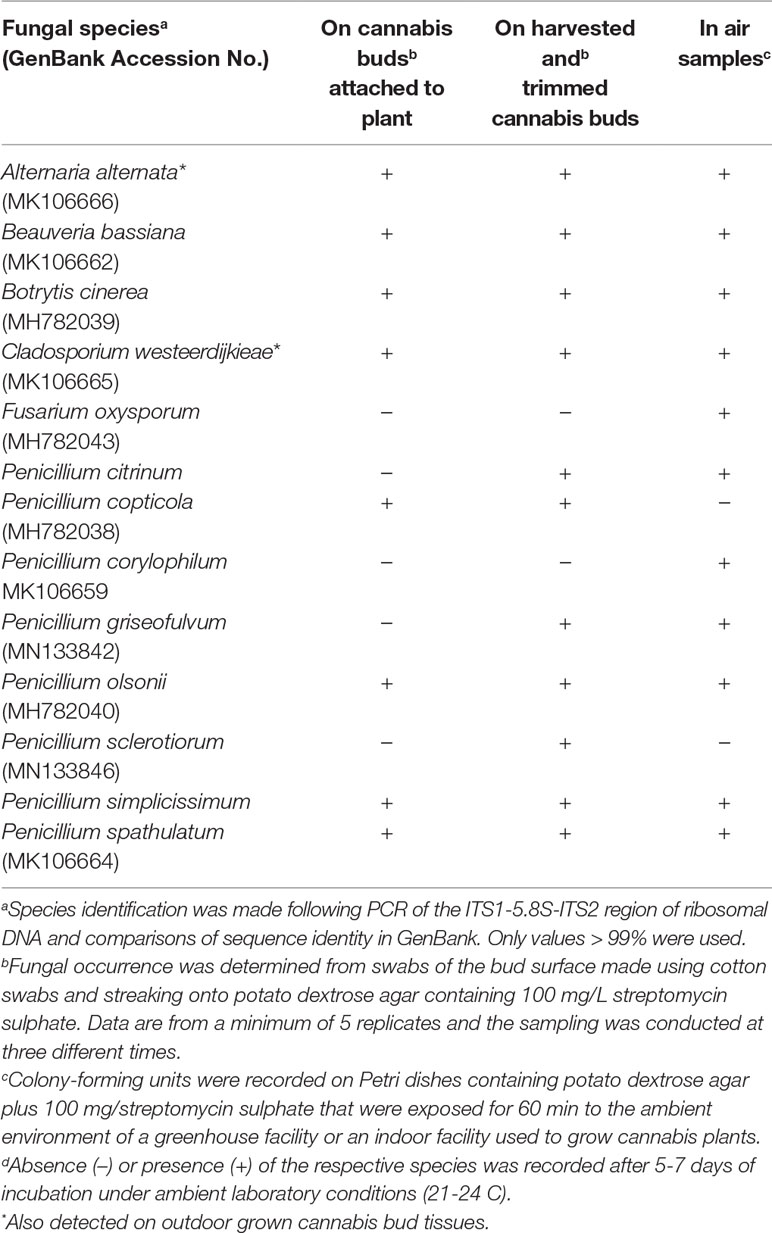

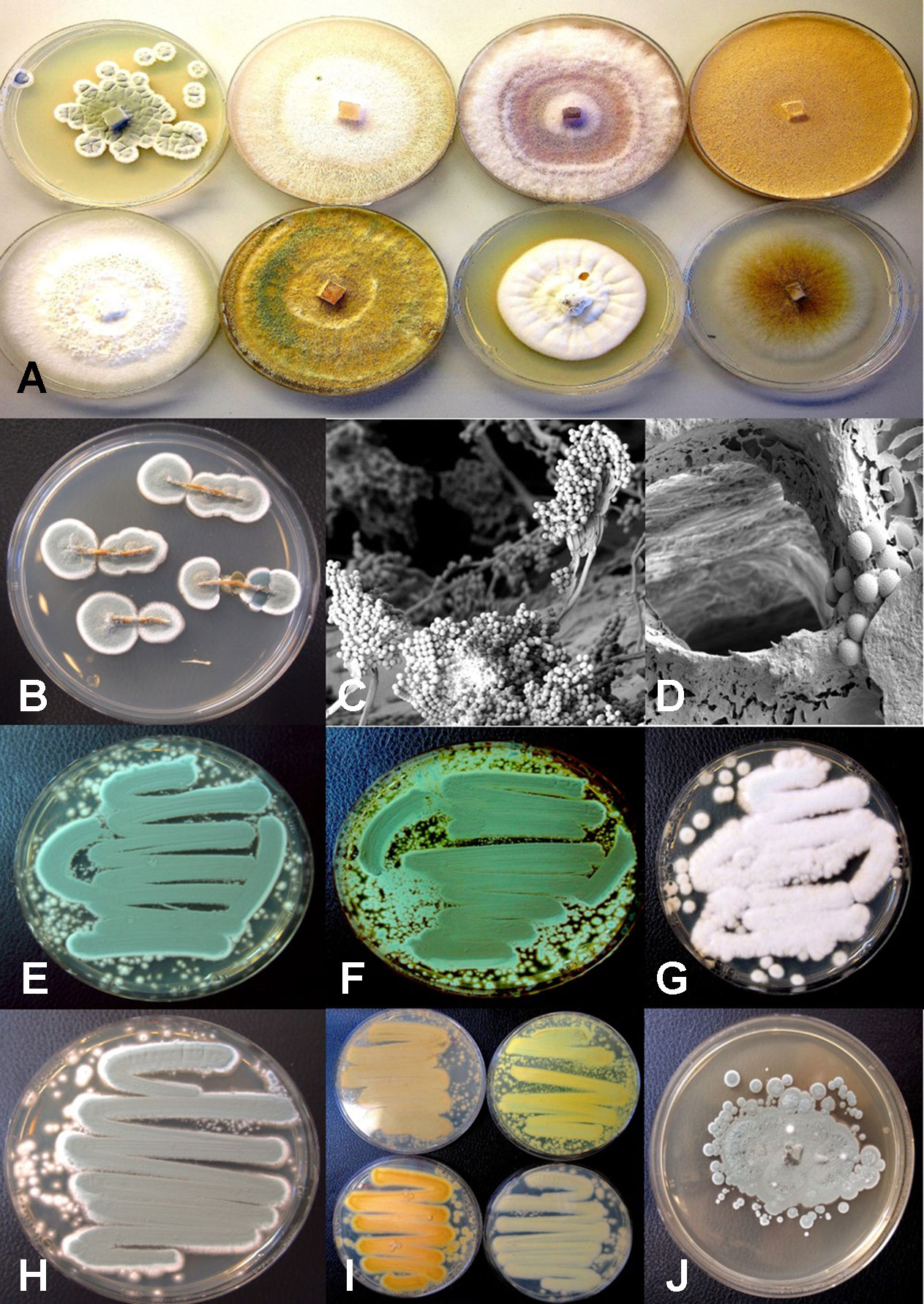

Using ITS1-ITS2 rDNA sequence comparisons, up to six species of Penicillium were identified in the collection of isolates made from indoor air samples or those originating from Cannabis bud tissues (Table 1). These were Penicillium spathulatum (Figure 14E), Penicillium citrinum (Figure 14F), Penicillium simplicissimum (Figure 14G), P. olsonii (Figure 14H), and P. griseofulvum. These colonies were subcultured by streaking a spore mass collected using a cotton swab onto PDA+S dishes where they grew and sporulated within 96 hours. The individual species produced distinct pigments in culture when viewed from below, ranging from dark gray to yellow, tan brown, and beige that facilitated identification (Figure 14I). To obtain an estimate of the overall frequency of recovery, from a total of 124 isolates of Penicillium species subcultured in this study, 48 (38%) was P. spathulatum, 22 (17%) was P. citrinum, while P. simplicissimum and P. olsonii were recovered at 20 and 21% each, respectively. A low recovery of P. griseofulvum and Penicillium sclerotiorum was also recorded (2% each).

|

|

Discussion

Pathogenic fungi that cause diseases, as well as molds that affect cannabis growth and quality, are documented in this study. Molds are defined as fungi present on living or dead plant materials that are not associated with disease symptoms and may be present as incidental contaminants in the air or on growing substrates, or be part of the succession of microbes that decompose plant materials. These pathogens and molds were found to occur on cannabis plants during cultivation in greenhouse- and indoor-controlled environment growing facilities in British Columbia and Ontario, as well as in outdoor field environments. There is a scarcity of previous research on this topic, and many of the fungi and molds described here are previously unreported from cannabis. In addition, we describe the presence of endophytic fungi (those that occur internally within plant tissues without causing any apparent symptoms). No apparent disease symptoms that could be ascribed to bacterial or viral infections were noted in this study.

McPartland[1][2][7] has identified a range of plant pathogens and molds that affect cannabis during production, and recent research has described the use of molecular-based culture-independent approaches to detect molds that occur on dried cannabis products.[8][9][10] Additional research has described the occurrence of a range of culturable fungal and bacterial species that inhabit cannabis and hemp tissues internally.[11][12][13] These previous studies demonstrate the broad diversity of microbes that can be present on or associated with cannabis tissues, with some of those microbes being beneficial and others detrimental to plant growth. Our results confirm the occurrence of a range of pathogens and molds on cannabis plants and furthermore identify the potential origins and spread of these microbes within different growing environments.

On root systems of Cannabis plants, pathogens that included species of Fusarium and Pythium caused browning and decay on roots that resulted in stunted growth, yellowing, and sometimes death of the affected plants. Up to four species of Pythium and three of Fusarium were identified. One new species reported here (P. catenulatum) was recovered at a low frequency (4% of total isolates). While this species has been shown to cause root rot on soybean and corn seedlings[14], its pathogenicity on Cannabis plants awaits confirmation. Potential sources of inoculum of these pathogens include contaminated growing substrates, diseased cuttings, and airborne or waterborne propagules, as well as residual inoculum from previous crops. Reproduction of these pathogens on diseased tissues can further add to the inoculum load and lead to further spread within a Cannabis growing facility. Sanitization methods are needed to ensure that introduction and spread of pathogens within a Cannabis growing facility are minimized. Foliar pathogens such as powdery mildew and Botrytis bud rot can similarly spread as air-borne inoculum or through vegetative propagation. Both of these pathogens are known to reduce growth and quality of Cannabis plants, and disease management is difficult. In the case of Botrytis, infection of inflorescences during production can lead to significant post-harvest losses during storage. A recent review study by AbuQamar et al. describes approaches to management of diseases caused by B. cinerea.[15] Monitoring studies on pathogen and mold spore levels within Cannabis growing facilities would provide useful insights into the diversity and changes that occur in these populations.

In the present study, repeated monitoring studies were conducted in an indoor growing environment and a greenhouse environment over a six-week and four-week period, respectively. We observed that indoor growing facilities harbor a range of airborne Penicillium species, as well as Cladosporium (identified as C. westerdijkieae, formerly Cladosporium cladosporioides)[16], and overall population levels were lower compared to a greenhouse growing environment, which had higher levels of Cladosporium. The populations of the different fungi detected in the indoor growing facility varied over time, and there was no consistent trend observed. Applications of the biocontrol products RootShield (containing T. harzianum) and BotaniGard (containing B. bassiana) was shown to result in airborne spread as detected on the PDA+S dishes in the weeks following application. From field-grown bud samples, the primary mold identified was Cladosporium, followed by Alternaria, which are molds predominantly found outdoors during the summer.[17][18]

There are likely to be seasonal differences in the occurrence of these airborne contaminants.[18][19][20] On industrial hemp plants grown under field conditions, higher frequencies of fungi have been found during the month of July compared to June or August.[13] The highest proportions of fungi have been recovered from hemp leaf tissues, compared to petioles and seeds, and have included Alternaria and Cladosporium, in addition to other genera.[13] In contrast to the findings of previous researchers[11][12] and those reported in the present study, however, no species of Penicillium have been recovered from field-grown hemp tissues.[13] This could potentially reflect a difference between indoor and outdoor growing environments with regard to microbial communities, or differences between marijuana and hemp plants in their endophytic composition. Thompson et al.[10] reported the following genera, in decreasing intensity of detection, to be present on cannabis buds obtained from dispensaries in Northern California (growing environments were not specified): Penicillium, Cladosporium, Golovinomyces, Aspergillus, Alternaria, Botryotinia, Chaetomium, and a low frequency of Fusarium.[10] Most of these fungi are common constituents of outdoor and indoor air samples[21], and all of them were identified in the present study to occur on cannabis tissues to varying extents. Other studies have confirmed the presence of Penicillium and Aspergillus species as contaminants on cannabis buds[7][8][9], as well as low detection of F. oxysporum.[9] These molds are present in soil and on plant materials[22][23] and can also be found in the greenhouse environment[24][25][26] and in residential homes.[17][18][19] Surprisingly, the overall recovery of Aspergillus species on potato dextrose agar in the present study was low (less than 1% of the total fungi quantified). This could reflect their lower overall numbers or the difficulty in recovery of this genus, which has been reported to grow slowly on many culture media.[8] Two species were recovered in this study—Aspergillus sydowii and A. terreus—which grew slowly in culture on PDA (Figure 14J). Both species can be found in soil and can contaminate food products, though A. terreus has been reported to be an endophyte.[27]

The occurrence of a broad diversity of fungi, some of which are potential plant pathogens, in unsterilized coco fiber commonly used as a substrate for growing Cannabis plants, was demonstrated in this study. Coco is produced from the processing of coconut husks that are grown primarily in tropical climates and then dried and bagged for export. Methods for sterilization of coco products (if used) are not always stated, and if conducted, may be ineffective at eliminating the vast diversity of fungi that are naturally associated with the progressive celluloytic decomposition of this plant material. Fungi present in coco fiber, and consequently that could end up colonizing Cannabis plant tissues, include C. globosum, P. chrysogenum and P. olsonii, A. niger, T. harzianum, T. versicolor, and B. bassiana, as well as species of Simplicillium and Lecanicillium (Akanthomyces). Gautam et al.[11] recovered P. chrysogenum and A. niger from Cannabis leaf, stem, and petiole tissues from field-grown plants. Both B. bassiana and T. harzianum are known to have endophytic activity.[28][29][30][31] Trametes versicolor is a widely distributed wood-decomposing Basidiomycete and a secondary plant pathogen, while Simplicillium and Lecanicillium are both entomopathogens and endophytes.[31][32][33] Chaetomium globosum is commonly found in indoor environments.[34] The recovery of such a broad range of fungi from Cannabis plants grown in coco fiber in an indoor environment indicates propagules of these fungi that were likely to have been present in the coco growing medium.

Endophytic colonization of Cannabis stem tissues, and the progression of internal colonization from the crown region to upper portions of the plant by some of the fungi recovered from surface-sterilized leaf, petiole, and axillary buds, was demonstrated in this study. The occurrence of endophytic fungi, as well as a broad range of bacterial species, has been previously reported in Cannabis and industrial hemp tissues[11][12][13], as well as in many other plant species.[35] Our findings indicate that the growing substrate can harbor fungi (as well as a wide range of bacteria, which were not quantified), and movement through the plant from the roots and crown tissues into the pith tissues can distribute the microbes. The pith of plants consists of loosely organized spongy parenchyma cells which store and transport water and nutrients.[36] In Cannabis plants, the pith also disintegrates to produce a hollow central core (see Figure 11E) that can allow for movement of mycelium and spores, as well as bacterial cells, readily up through the plant. Spores of Penicillium were observed to be present in the pith tissues. As well, the potential for colonization of exposed stem surfaces following pruning, followed by internal colonization of the stem, presumably also through the pith tissues into the plant, was demonstrated. Whether this mode of infection can result in transmission of pathogens through vegetative cuttings used for propagation or not remains to be confirmed. The occurrence of damping off symptoms (see Figures 3D, E) associated with F. oxysporum on stem cuttings suggests that spread from the pith tissues may have taken place.

Epiphytic colonization from spores of common aerially dispersed fungi such as Cladosporium and Penicillium onto Cannabis tissues is also an important source of mold contamination. In particular, mature inflorescences that secrete resinous compounds from glandular trichomes (Andre et al., 2016) are exposed to pre- and post-harvest contamination by airborne spores that are deposited and adhere to the sticky surface, as demonstrated through scanning electron microscopic observations in this study. Furthermore, colonization of cut and exposed stem surfaces during pruning practices can allow entry of these fungi and their potential establishment as endophytes in Cannabis plants, as previously discussed. Previous studies have associated endophytic colonization of Cannabis tissues by bacteria and fungi with potentially beneficial effects on the plant, such as protection against diseases, enhancement of plant growth, increased uptake of nutrients, etc.[11][12][13] However, there are no studies confirming the in situ benefits to Cannabis plants attributable to these endophytes. The proposed antagonism to pathogens has been based solely on in vitro antagonism experiments[11][12][13] and their ability to produce anti-fungal compounds[13] or zones of inhibition on agar media.[11][12] As stated by Schulz and Boyle[37], “endophytes represent, both as individuals and collectively, a continuum of mostly variable associations: mutualism, commensalism, latent pathogenicity, and exploitation.” This includes saprophytes growing on dead or senescent tissues after an endophytic growth phase in the plant, avirulent microorganisms, latent pathogens, and virulent pathogens in the early stages of infection, as well as beneficial microbes.[37] Additional studies are required to confirm at which point in the spectrum of these interactions the endophytes reported in Cannabis plants may exert beneficial/detrimental effects on growth and quality of the plants.

In forest tree species, endophytic fungal species are commonly present and can remain latent until environmental conditions cause them to become pathogens.[38][39] Therefore, their beneficial or mutualistic roles can remain inconclusive. Not all endophytes can be assumed to be beneficial through their association with, and recovery from, internal tissues of Cannabis plants or because they produce anti-microbial compounds in vitro. Our findings suggest that a large proportion of fungal endophytes of Cannabis arise as contaminants originating from the growing medium or the external environment. Many of the fungi can impart negative consequences to the plant; they can inhabit the pith tissues and cause discoloration, they can end up on the inflorescences and result in higher mold counts, or they can interfere with vegetative propagation of the plant through cuttings or using tissue culture micropropagation (authors' unpublished observations). Some of the genera reported to be endophytic, e.g., Penicillium and Aspergillus[11][12], are also mycotoxin producers.[8][10][40][41] They have also been associated with asthmatic and allergic conditions when present in high numbers in indoor environments.[17][18] Cladosporium—commonly found on plant materials and in indoor environments—may also produce mycotoxins[42] and contribute to the indoor mycoflora associated with asthmatic conditions.[16] Therefore, a detailed analysis of the potential negative effects of endophytic fungi on growth and quality of Cannabis plants is required.

The most prevalent Penicillium species recovered in the present study from Cannabis bud tissues and indoor air samples was P. spathulatum, followed by P. simplicissimum and P. citrinum. In a previous study, Penicillium copticola was isolated at a high frequency from the twigs, leaves, and apical and lateral buds of Cannabis plants[12], and P. olsonii was isolated from Cannabis stems and buds.[6] These species of Penicillium are reported to occur as indoor molds (P. spathulatum, P. citrinum), are found on decaying vegetation (P. simplicissimum, P. olsonii), and occur as contaminants of food and feedstuff (P. spathulatum, P. simplicissimum, P. citrinum). Penicillium spathulatum is present in indoor environments and is also found in soil, as well as on food and feedstuff, and occurs as an endophyte. It has been reported to produce the anticancer compound asperphenamate.[43] Penicillium simplicissimum occurs as a contaminant in food and is commonly found in decaying vegetation and produces a range of mycotoxins in culture. It is also reported to occur as an endophyte and promotes plant growth.[44] Penicillium citrinum has a worldwide distribution and has been isolated from various substrates such as tropical soil, cereals, spices, and indoor environments[45]; it is reported to be an endophyte and promotes plant growth.[22][27][46] Citrinin, a nephrotoxin mycotoxin named after P. citrinum, is produced by P. citrinum. Penicillium olsonii is found in decaying vegetation and soil, as well as on foods, and causes a post-harvest fruit rot of tomato[47][48]; it was the main Penicillium species recovered from field-grown dried Cannabis buds in this study. Penicillium chrysogenum was isolated from pith tissues in the current study and has a worldwide distribution, but is commonly found in indoor environments, especially in damp locations.[49][50] The species is most well known for its production of the antibiotic penicillin.[51] Penicillium griseofulvum (syn. Penicillium patulum) has been shown to cause blue mold disease on apples[52] and has been isolated from other fruit species and various environments such as desert soil, cereal grains, and animal feed. Penicillium griseofulvum is able to produce the mycotoxins patulin and roquefortine C. Considering that P. griseofulvum is frequently isolated from apple, corn, wheat, barley, flour, walnuts, and from meat products, it could be a potential source of roquefortine C in food.[53] Penicillium griseofulvum is known to also produce a useful secondary metabolite, griseofulvin. Besides its recognized antifungal properties against a wide variety of plant pathogens, griseofulvin has been used for many years in medical and veterinary applications. Finally, Penicillium corylophilum was present in air samples but was not detected on Cannabis tissues. It is not known to what extent that, if any, various secondary metabolites (extrolites) produced by these Penicillium species in culture are also produced in harvested Cannabis buds, stems, and leaves harboring these fungi. The longevity of spores of Penicillium and Cladosporium species following deposition on Cannabis bud tissues is unknown.

The process of mechanical trimming of Cannabis buds after harvest (wet trim) and the associated wounding of the tissues caused an observable increase in the recovery of Penicillium and Cladosporium colonies, compared to untrimmed harvested buds, indicating their populations on the surface of tissues were increased. Wounding is known to increase the colonization of a range of fruits by Penicillium after harvest.[54][55] Exudation of nutrients from cut tissues would have enhanced the proliferation of these opportunistic molds. In addition, internally borne mold spores, e.g., in the pith, could have been released through wounding of tissues and become airborne. Cladosporium is commonly found in indoor environments[16] and is one of the most commonly identified molds, especially in the summer.[17][18] It was found on field-grown Cannabis buds in this study, together with Alternaria. Internal growth and sporulation of Penicillium species within Cannabis stem tissues and damage during harvest could also release spores that could subsequently contaminate bud tissues. Management of these molds on Cannabis buds would require careful handling, drying, and storage under conditions that discourage their further proliferation. The fact that they are so ubiquitous outdoors and indoors, and are prolific spore producers, as well as are harbored internally, provides additional challenges to producers aiming to achieve a high-quality, minimally contaminated product.

Conclusion

The results from this study illustrate the challenges facing Cannabis producers with regard to management of diseases and molds found on plants grown in different production environments. Airborne saprophytic molds that end up on Cannabis inflorescences as contaminants primarily include Cladosporium and several different Penicillium species. In addition, Botrytis bud rot can pose challenges to producers during production and also as a post-harvest problem. Most of the root-infecting pathogens are not visibly detrimental to plant growth unless infection occurs early; however, destruction of roots can result in as-yet undetermined reductions in yield and quality. Powdery mildew infection is commonly present in most production facilities and requires proactive management and identification methods, including the consideration of disease-resistant genetic selections. The identification of diseases and molds of Cannabis in the present study should foster additional research into their epidemiology and management. The response of different Cannabis strains (genotypes) to the various pathogens identified in the current study is an important aspect of disease management, but at present, there is no published information on this topic, which will require additional research to be conducted in order to provide Cannabis producers with additional approaches to pathogen reduction.

Acknowledgements

We thank S. Chen for providing technical assistance in the work.

Author contributions

ZP formulated the concept of the project and designed the experiments, supervised the project and wrote the manuscript and prepared the figures. DC, CS, SL and JH performed the experiments and data analysis. DS performed the scanning electron microscopy. All authors discussed the results and edited the manuscript.

Funding

Funding was provided through an industrial financial contribution from Agrima Botanicals and a Collaborative Research and Development (CRD) Grant from the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada (NSERC). Additional funding was provided from the B.C. Ministry of Agriculture and Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada through the Canadian Agricultural Partnership (CAP) Program.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 McPartland, S.M. (1991). "Common names for diseases of Cannabis sativa L.". Plant Disease 75: 226–7.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 McPartland, J.M. (1996). "A review of Cannabis diseases". Journal of International Hemp Association 3 (1): 19–23. http://www.internationalhempassociation.org/jiha/iha03111.html.

- ↑ Small, E. (2017). Cannabis: A Complete Guide. CRC Press. ISBN 9781498761635.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 Punja, Z.K.; Scott, C.; Chen, S. (2018). "Root and crown rot pathogens causing wilt symptoms on field-grown marijuana (Cannabis sativa L.) plants". Canadian Journal of Plant Pathology 40 (4): 528–41. doi:10.1080/07060661.2018.1535470.

- ↑ Punja, Z.K.; Rodriguez, G. (2018). "Fusarium and Pythium species infecting roots of hydroponically grown marijuana (Cannabis sativa L.) plants". Canadian Journal of Plant Pathology 40 (4): 498–513. doi:10.1080/07060661.2018.1535466.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Punja, Z.K. (2018). "Flower and foliage-infecting pathogens of marijuana (Cannabis sativa L.) plants". Canadian Journal of Plant Pathology 40 (4): 514–27. doi:10.1080/07060661.2018.1535467.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 McPartland, J.M. (1994). "Microbiological contaminants of marijuana". Journal of the International Hemp Association 1 (2): 41–44. http://www.internationalhempassociation.org/jiha/iha01205.html.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 8.3 McKernan, K.; Spangler, J.; Helbert, Y. et al. (2016). "Metagenomic analysis of medicinal Cannabis samples; pathogenic bacteria, toxigenic fungi, and beneficial microbes grow in culture-based yeast and mold tests". F1000Research 5: 2471. doi:10.12688/f1000research.9662.1. PMC PMC5089129. PMID 27853518. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5089129.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 McKernan, K.; Spangler, J.; Zhang, L. et al. (2015). "Cannabis microbiome sequencing reveals several mycotoxic fungi native to dispensary grade Cannabis flowers". F1000Research 4: 1422. doi:10.12688/f1000research.7507.2. PMC PMC4897766. PMID 27303623. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4897766.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 10.3 Thompson 3rd, G.R.; Tuscano, J.M.; Dennis, M. et al. (2017). "A microbiome assessment of medical marijuana". Clinical Microbiology and Infection 23 (4): 269–70. doi:10.1016/j.cmi.2016.12.001. PMID 27956269.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 11.3 11.4 11.5 11.6 11.7 Gautam, A.K.; Kant, M.; Thakur, Y. (2012). "Isolation of endophytic fungi from Cannabis sativa and study their antifungal potential". Archives of Phytopathology and Plant Protection 46 (6): 627–35. doi:10.1080/03235408.2012.749696.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 12.2 12.3 12.4 12.5 12.6 12.7 Kusari, P.; Kusari, S.; Spiteller, M. et al. (2013). "Endophytic fungi harbored in Cannabis sativa L.: Diversity and potential as biocontrol agents against host plant-specific phytopathogens". Fungal Diversity 60: 137–51. doi:10.1007/s13225-012-0216-3.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 13.2 13.3 13.4 13.5 13.6 13.7 Scott, M.; Rani, M.; Samsatly, J. et al. (2018). "Endophytes of industrial hemp (Cannabis sativa L.) cultivars: identification of culturable bacteria and fungi in leaves, petioles, and seeds". Canadian Journal of Microbiology 64 (10): 664-80. doi:10.1139/cjm-2018-0108. PMID 29911410.

- ↑ Dorrance, A.E.; Berry, S.A.; Lipps, P.E. (2004). "Characterization of Pythium spp. from Three Ohio Fields for Pathogenicity on Corn and Soybean and Metalaxyl Sensitivity". Plant Health Progress 5 (1). doi:10.1094/PHP-2004-0202-01-RS.

- ↑ AbuQamar, S.; Moustafa, K.; Tran, L.S. (2017). "Mechanisms and strategies of plant defense against Botrytis cinerea". Critical Reviews in Biotechnology 37 (2): 262-274. doi:10.1080/07388551.2016.1271767. PMID 28056558.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 16.2 Bensch, K.; Groenwald, J.Z.; Meijer, M. et al. (2018). "Cladosporium species in indoor environments". Studies in Mycology 89: 177–301. doi:10.1016/j.simyco.2018.03.002. PMC PMC5909081. PMID 29681671. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5909081.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 17.2 17.3 Ren, P.; Jankun, T.M.; Leaderer, B.P. (1999). "Comparisons of seasonal fungal prevalence in indoor and outdoor air and in house dusts of dwellings in one Northeast American county". Journal of Exposure Analysis and Environmental Epidemiology 9 (6): 560–8. doi:10.1038/sj.jea.7500061. PMID 10638841.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 18.2 18.3 18.4 de Ana, S.G.; Torres-Rodríguez, J.M.; Ramírez, E.A. et al. (2006). "Seasonal distribution of Alternaria, Aspergillus, Cladosporium and Penicillium species isolated in homes of fungal allergic patients". Journal of Investigational Allergology & Clinical Immunology 16 (6): 357–63. PMID 17153883.

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 Kuo, Y.-M.; Li, C.-S. (1994). "Seasonal fungus prevalence inside and outside of domestic environments in the subtropical climate". Atmospheric Environment 28 (19): 3125–30.

- ↑ Khan, N.N.; Wilson, B.L. (2003). "An environmental assessment of mold concentrations and potential mycotoxin exposures in the greater Southeast Texas area". Journal of Environmental Science and Health, Part A 38 (12): 2759–72. doi:10.1081/ese-120025829. PMID 14672314.

- ↑ Meklin, T.; Reponen, T.; McKinstry, C. et al. (2007). "Comparison of mold concentrations quantified by MSQPCR in indoor and outdoor air sampled simultaneously". Science of the Total Environment 382 (1): 130–4. doi:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2007.03.031. PMC PMC2233941. PMID 17467772. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2233941.

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 Houbraken, J.A.M.P.; Frisvad, J.C.; Samson, R.A. (2010). "Taxonomy of Penicillium citrinum and related species". Fungal Diversity 44: 117–33. doi:10.1007/s13225-010-0047-z.

- ↑ Garba, M.H.; Makun, H.A.; Jigam, A.A. et al. (2017). "Incidence and toxigenicity of fungi contaminating sorghum from Nigeria". World Journal of Microbiology 3 (1): 105–14. https://premierpublishers.org/wjm/220320177210.

- ↑ Gamliel, A.; Katan, T.; Yunis, H. et al. (1996). "Fusarium Wilt and Crown Rot of Sweet Basil: Involvement of Soilborne and Airborne Inoculum". Phytopathology 86: 56–62. doi:10.1094/Phyto-86-56.

- ↑ Katan, T.; Shlevin, E.; Katan, J. (1997). "Sporulation of Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. lycopersici on Stem Surfaces of Tomato Plants and Aerial Dissemination of Inoculum". Phytopathology 87 (7): 712–19. doi:10.1094/PHYTO.1997.87.7.712. PMID 18945093.

- ↑ Punja, Z.K.; Rogriguez, G.; Tirajoh, A. et al. (2016). "Role of fruit surface mycoflora, wounding and storage conditions on post-harvest disease development on greenhouse tomatoes". Canadian Journal of Plant Pathology 38 (4): 448–59. doi:10.1080/07060661.2016.1245914.

- ↑ 27.0 27.1 Waqas, M.; Khan, A.L.; Hamayun, M. et al. (2015). "Endophytic fungi promote plant growth and mitigate the adverse effects of stem rot: An example of Penicillium citrinum and Aspergillus terreus". Journal of Plant Interactions 10 (1): 280–87. doi:10.1080/17429145.2015.1079743.

- ↑ Ownley, B.H.; Griffin, M.R.; Klingeman, W.E. et al. (2008). "Beauveria bassiana: Endophytic colonization and plant disease control". Journal of Invertebrate Pathology 98 (3): 267-70. doi:10.1016/j.jip.2008.01.010. PMID 18442830.

- ↑ Ownley, B.H.; Gwinn, K.D.; Vega, F.E. (2010). "Endophytic fungal entomopathogens with activity against plant pathogens: Ecology and evolution". BioControl 55: 113–28. doi:10.1007/s10526-009-9241-x.

- ↑ Taribuka, J.; Wibowo, A.; Widyastuti, S.M. et al. (2017). "Potency of six isolates of biocontrol agents endophytic Trichoderma against fusarium wilt on banana". Journal of Degraded and Mining Lands Management 4 (2): 723–31. doi:10.15243/jdmlm.2017.042.723.

- ↑ 31.0 31.1 Vega, F.E. (2018). "The use of fungal entomopathogens as endophytes in biological control: A review". Mycologia 110 (1): 4–30. doi:10.1080/00275514.2017.1418578.

- ↑ Gurulingappa, P.; McGee, P.A.; Sword, G. (2011). "Endophytic Lecanicillium lecanii and Beauveria bassiana reduce the survival and fecundity of Aphis gossypii following contact with conidia and secondary metabolites". Crop Protection 30 (3): 349–53. doi:10.1016/j.cropro.2010.11.017.

- ↑ Lim, S.Y.; Lee, S.; Kong, H.G. et al. (2014). "Entomopathogenicity of Simplicillium lanosoniveum Isolated in Korea". Mycobiology 42 (4): 317–21. doi:10.5941/MYCO.2014.42.4.317. PMC PMC4298834. PMID 25606002. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4298834.

- ↑ Wang, X.W.; Houbraken, J.; Groenewald, J.Z. et al. (2016). "Diversity and taxonomy of Chaetomium and chaetomium-like fungi from indoor environments". Studies in Mycology 84: 145–224. doi:10.1016/j.simyco.2016.11.005. PMC PMC5226397. PMID 28082757. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5226397.

- ↑ Bamisile, B.S.; Dash, C.K.; Akutse, K.S. et al. (2018). "Fungal Endophytes: Beyond Herbivore Management". Frontiers in Microbiology 9: 544. doi:10.3389/fmicb.2018.00544. PMC PMC5876286. PMID 29628919. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5876286.

- ↑ Fujimoto, M.; Sazuka, T.; Oda, Y. et al. (2018). "Transcriptional switch for programmed cell death in pith parenchyma of sorghum stems". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 115 (37): E8783-E8792. doi:10.1073/pnas.1807501115. PMC PMC6140496. PMID 30150370. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6140496.

- ↑ 37.0 37.1 Schulz, B.; Boyle, C. (2006). "What are endophytes?". In Schulz, B.; Boyle, C.; Sieber, T.. Microbial Root Endophytes. Springer. pp. 1–13. doi:10.1007/3-540-33526-9_1. ISBN 9783540335252.

- ↑ Arnold, A.E. (2007). "Understanding the diversity of foliar endophytic fungi: Progress, challenges, and frontiers". Fungal Biology Reviews 21 (2–3): 51–66. doi:10.1016/j.fbr.2007.05.003.

- ↑ Sieber, T.N. (2007). "Endophytic fungi in forest trees: Are they mutualists?". Fungal Biology Reviews 21 (2–3): 75–89. doi:10.1016/j.fbr.2007.05.004.

- ↑ Abbott, S.P. (2002). "Mycotoxins and Indoor Molds". Indoor Environment CONNECTIONS 3 (4): 14–24. http://nlmlab.com/sites/default/files/PDFs/NLML-Mycotoxins.pdf.

- ↑ Perrone, G.; Susca, A. (2017). "Penicillium Species and Their Associated Mycotoxins". Methods in Molecular Biology 1542: 107–19. doi:10.1007/978-1-4939-6707-0_5. PMID 27924532.

- ↑ Alwatban, M.A.; Hadi, S.; Moslem, M.A. (2014). "Mycotoxin Production in Cladosporium Species Influenced by Temperature Regimes". Journal of Pure and Applied Microbiology 8 (5): 4061-4069. https://microbiologyjournal.org/archive_mg/jmabsread.php?snoid=2222.

- ↑ Fisban, J.C.; Houbraken, J.; Popma, S. et al. (2013). "Two new Penicillium species Penicillium buchwaldii and Penicillium spathulatum, producing the anticancer compound asperphenamate". FEMS Microbiology Letters 339 (2): 77–92. doi:10.1111/1574-6968.12054. PMID 23173673.

- ↑ Hossain, M.M.; Sultana, F.; Kubota, M. et al. (2007). "The plant growth-promoting fungus Penicillium simplicissimum GP17-2 induces resistance in Arabidopsis thaliana by activation of multiple defense signals". Plant & Cell Physiology 48 (12): 1724–36. doi:10.1093/pcp/pcm144. PMID 17956859.

- ↑ Samson, R.A.; Hoekstra, E.S.; Frisvad, J.C. (2004). Introduction to food- and airborne fungi (7th ed.). Utrecht: Centraalbureau voor Schimmelcultures. ISBN 9789070351526.

- ↑ Khan, S.A.; Hamayun, M.; Yoon, H. et al. (2008). "Plant growth promotion and Penicillium citrinum". BMC Microbiology 8: 231. doi:10.1186/1471-2180-8-231. PMC PMC2631606. PMID 19099608. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2631606.

- ↑ Chatteron, S.; Wylie, A.C.; Punja, Z.K. (2012). "Fruit infection and postharvest decay of greenhouse tomatoes caused by Penicillium species in British Columbia". Canadian Journal of Plant Pathology 34 (4): 524–35. doi:10.1080/07060661.2012.710069.

- ↑ Anjum, N.; Shahid, A.A.; Iftikhar, S. et al. (2017). "First Report of Postharvest Fruit Rot of Tomato (Lycopersicum esculentum Mill.) Caused by Penicillium olsonii in Pakistan". Plant Disease 102 (2): 451. doi:10.1094/PDIS-08-17-1257-PDN.

- ↑ Samson, R.A.; Houbraken, J.; Thrane, U. et al. (2010). Food and Indoor Fungi (1st ed.). Utrecht, the Netherland : CBS-KNAW Fungal Biodiversity Centre. ISBN 9789070351823.

- ↑ Andersen, B.; Frisvad, J.C.; Søndergaard, I. et al. (2011). "Associations between fungal species and water-damaged building materials". Applied and Environmental Microbiology 77 (12): 4180–8. doi:10.1128/AEM.02513-10. PMC PMC3131638. PMID 21531835. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3131638.

- ↑ Samson, R.A.; Hadlok, R.; Stolk, A.C. (1977). "A taxonomic study of the Penicillium chrysogenum series". Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek 43 (2): 169–75. doi:10.1007/BF00395671. PMID 413477.

- ↑ Spadaro, D.; Lorè, A.; Amatulli, M.T. et al. (2011). "First Report of Penicillium griseofulvum Causing Blue Mold on Stored Apples in Italy (Piedmont)". Plant Disease 95 (1): 76. doi:10.1094/PDIS-08-10-0568. PMID 30743679.

- ↑ Samson, R.A.; Frisvad, J.C. (2004). "Polyphasic taxonomy of Penicillium subgenus Penicillium: A guide to identification of food and air-borne terverticillate Penicillia and their mycotoxins". Studies in Mycology 49: 1–174. https://www.studiesinmycology.org/index.php/issue/51-studies-in-mycology-no-49.

- ↑ Kavanagh, J.A.; Wood, R.K.S. (1967). "The role of wounds in the infection of oranges by Penicillium digitatum Sacc". Annals of Applied Biology 60 (3): 375–83. doi:10.1111/j.1744-7348.1967.tb04490.x.

- ↑ Vilanova, L.; Viñas, I.; Torres, R. et al. (2014). "Increasing maturity reduces wound response and lignification processes against Penicillium expansum (pathogen) and Penicillium digitatum (non-host pathogen) infection in apples". Postharvest Biology and Technology 88: 54–60. doi:10.1016/j.postharvbio.2013.09.009.

Notes

This presentation is faithful to the original, with only a few minor changes to presentation. Some grammar and punctuation was cleaned up to improve readability. In some cases important information was missing from the references, and that information was added. The original article lists references in alphabetical order; this version lists them by order of appearance, by design.