Journal:Definitions, components and processes of data harmonization in healthcare: A scoping review

| Full article title | Definitions, components and processes of data harmonization in healthcare: A scoping review |

|---|---|

| Journal | BMC Medical Informatics and Decision Making |

| Author(s) | Schmidt, Bey-Marrié; Colvin, Christopher J.; Hohlfeld, Ameer; Leon, Natalie |

| Author affiliation(s) | South African Medical Research Council, University of Cape Town, University of Virginia, Brown University |

| Primary contact | Online contact form |

| Year published | 2020 |

| Volume and issue | 20 |

| Page(s) | 222 |

| DOI | 10.1186/s12911-020-01218-7 |

| ISSN | 1472-6947 |

| Distribution license | Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International |

| Website | https://bmcmedinformdecismak.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12911-020-01218-7 |

| Download | https://bmcmedinformdecismak.biomedcentral.com/track/pdf/10.1186/s12911-020-01218-7 (PDF) |

Abstract

Background: Data harmonization (DH) has is increasingly being used by health managers, information technology specialists, and researchers as an important intervention for routine health information systems (RHISs). It is important to understand what DH is, how it is defined and conceptualized, and how it can lead to better health management decision-making. This scoping review identifies a range of definitions for DH, its characteristics (in terms of key components and processes), and common explanations of the relationship between DH and health management decision-making.

Methods: This scoping review identified more than 2,000 relevant studies (date filter) written in English and published in PubMed, Web of Science, and CINAHL. Two reviewers independently screened records for potential inclusion for the abstract and full-text screening stages. One reviewer did the data extraction, analysis, and synthesis, with built-in reliability checks from the rest of the team. We developed a narrative synthesis of definitions and explanations of the relationship between DH and health management decision-making.

Results: Of the 181 studies ultimately included in this scoping review, 61 included synthesis definitions and concepts of DH in detail. From these, we identified six common terms for data harmonization: "record linkage," "data linkage," "data warehousing," "data sharing," "data interoperability," and "health information exchange." We also identified nine key components or characteristics of data harmonization: it involves (a) multi-step processes; (b) integration and harmonization of different databases; (c) the use of two or more databases; (d) the use of electronic data; (e) pooling of data using unique patient identifiers; (f) different types of data; (g) data found within and across different departments and institutions at facility, district, regional, and national levels; (h) different types of technical activities; and (i) a specific scope. The relationship between DH and health management decision-making is not well-described in the literature. Several studies mentioned health providers’ concerns about data completeness, data quality, terminology, and coding of data elements as barriers to data use for clinical decision-making.

Conclusion: To our knowledge, this scoping review was the first to synthesize definitions and concepts of DH and address the causal relationship between DH and health management decision-making. Future research is required to assess the effectiveness of data harmonization on health management decision-making.

Keywords: data harmonization, health information exchange, health information system, scoping review

Background

Data harmonization (DH) in healthcare is a digital, technology-based innovation that can potentially help routine health information systems (RHISs) function at their best. It can help organize and integrate large databases containing routine health information.[1] Designing, developing, and implementing DH interventions has the potential to strengthen aspects of the health system, by enhancing RHISs to a state of high-quality and relevant information that can support decisions, actions, and changes across all components and levels of the health system.[2][3] When RHISs are functioning properly, they can help health practitioners and managers identify and close gaps in health service delivery, as well as inform their planning, implementation, and monitoring of interventions.[4][5] They can also help address problems related to using different variables and indicators for collecting, analyzing, and reporting health information across healthcare administration and management programs[6], which is common in low-and-middle-income (LMIC) settings. Other challenges to effective RHIS functioning include the production of poor-quality data that cannot easily be exchanged, as well as programmatic fragmentation across levels of the health system, which can result in the duplication and excessive production of data.[7]

Lack of standardized data production processes, fragmentation of databases, and errors and duplication in data production are only some of the challenges of RHISs, which may, at first glance be categorized as technical challenges.[3][8] Solutions to such apparently technical challenges include introducing new data forms, setting up warning systems to detect potential errors, and developing algorithms for integrating different databases.

However, DH interventions for RHISs may not be used effectively if data production and utilization processes are viewed as merely technical. Given that RHISs are embedded in complex health systems, DH interventions to improve RHIS functions are also influenced by the broader setting, in which dynamic and complex social and technical factors interact.[9][10][11] There is a need to consider the influence of social factors as well. These may include people’s competencies in dealing with new data production processes, institutional values about data utilization, and existing relationships between data producers and decision-makers.[8][12][13]

There is growing recognition that the development and implementation of DH interventions occurs in multiple technical and social contexts, and that DH interventions may differ in definition, purpose, and intended outcomes.[14] As such, various terms are used to describe interventions with similar aims and activities to data harmonization. For example, terms such as "record linkage," "data warehousing," "data sharing," and "health information exchange" are all used to describe data harmonization-type activities[15][16][17]; it is not always clear to which extent these interventions are similar in practice, scope, and relevance. The use of multiple terms may not be a problem in itself, but a common understanding of the components and processes will bring more clarity about what actually constitutes "data harmonization," and it will make it easier to compare and appraise the relevance and usefulness of DH interventions across settings.

Although DH has the potential to enhance RHISs, it is still unclear whether or how it affects health management decision-making. In some cases, DH interventions may not directly improve management decision-making, especially when interventions are more focused on the technical aspects of data production and less on the organizational and behavioral aspects of data use for decision-making.[18] The scope of this review is to therefore understand the different ways in which DH is defined, to identify its components and processes, and to describe whether or how DH can affect health management decision-making. Greater clarity about the range of definitions, components, and processes of DH interventions, as well as its intended outcomes, can help to better evaluate DH's relevance, usefulness, and impact.[12]

Methods

This scoping review was conducted according to the methods outlined by Arksey and O’Malley.[19] They recommend a process that is “not linear but, requiring researchers to engage with each stage in a reflexive way” to achieve both "in-depth and broad" results. This review followed the standard steps for systematic reviews: identifying the research question, identifying relevant studies, selecting studies for inclusion, extracting data, and synthesizing data. These are detailed in our published study protocol.[20]

Study objectives

This scoping review appraised the definitions, components, and processes of data harmonization activities, and it provided a broad explanation of the relationship between data harmonization interventions and health management decision-making. The specific objectives are:

- 1. to identify and provide an overview of the key components and processes of data harmonization studies;

- 2. to identify and synthesize the various definitions of data harmonization in healthcare; and

- 3. to describe the relationship between data harmonization interventions and health management decision-making.

We took a stepped approach in addressing these objectives. All included studies were used to address the first objective. To address the second objective, we sampled studies that were using alternative terms for DH interventions and used those to identify, synthesize, and compare similarities and differences in definitions. While executing these two objectives, we identified a smaller number of studies that contributed to the third objective.

Identifying relevant studies

Eligibility criteria

Peer-reviewed studies and gray literature were considered eligible for inclusion into the scoping review if they provided a definition or description of DH, and or, a more detailed conceptual explanation (in the form of a model, framework, or process) of a DH intervention. Additionally, studies were eligible if they provided an explanation of the causal relationship between DH and health management decision-making (such as through improved quality and accessibility of harmonized information for management and/or the use of harmonized health information for management decision-making). We considered any studies concerned with different technical activities of DH (such as linking, merging, cleaning and transferring). After screening, only studies for which we could access full-text articles were eligible for inclusion in the review.

Search strategy

A systematic literature search was conducted in PubMed, CINAHL, and Web of Science for eligible studies from January 1, 2000 to September 30, 2018. We limited our search to as far back as 2000, as digital technology-based innovations began during this period (such as health information exchange) in high-income countries (predominantly in the United States of America), and researchers and health system managers in LMICs became more interested in the integration of large digital databases.[21] We present the search strategy in the study protocol.[20] Based on preliminary searches, we anticipated that these databases would yield the highest results. The search strategies included a combination of keywords and Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) related to data harmonization (concept A) and health information systems (concept B). There were no geographic restrictions, but for logistical reasons of time and resources, we only searched for English studies.

Selecting studies for inclusion

Screening records

The first reviewer (BS) conducted all the searches with the help of a librarian and collated the records in the EndNote reference management program, where duplicates were removed. Two reviewers, (BS) and second reviewer (AH), then independently screened the records (titles and abstracts) to assess eligibility for full-text review. BS and AH resolved conflicts that emerged at this stage by talking through the inclusion criteria and arriving at a joint decision.

The full-texts of potentially eligible studies were retrieved and assessed by the two reviewers (BS and AH). Final inclusion into the review was based on whether at a minimum the study had a definition or description of a DH intervention or referred to its relationship with health management decision-making. The first reviewer read all full-texts and the second reviewer only read a sample (roughly a third) of the full-texts to verify the first reviewer’s decision about inclusion. BS and AH disagreed on four studies, and after discussion, agreed to exclude the studies.

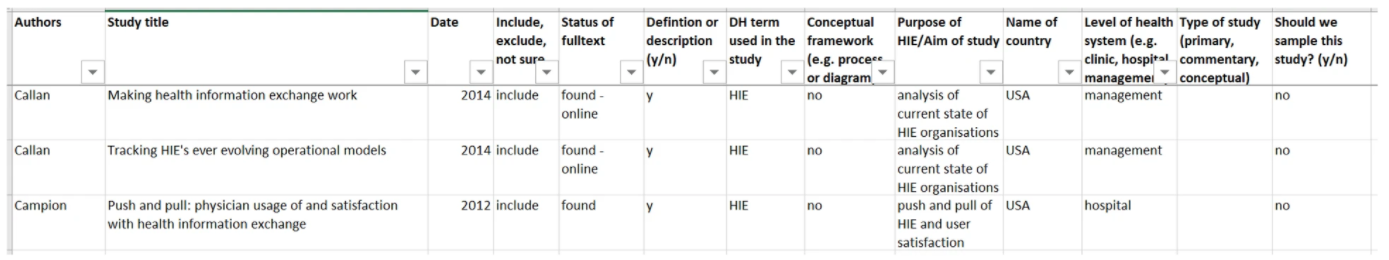

After finalizing screening, the two reviewers then mapped out the characteristics of included studies in an Excel spreadsheet. They recorded the name of the first author; the date; the type of study (primary, review, conceptual, commentary); the term used for the intervention they described (DH or alternative); the country in which the study took place; the level at which the intervention was implemented (frontline, management, research); and indicated whether or not there was a conceptual model, framework, diagram, or process description of DH and health management decision-making. This detailed mapping of study characteristics was useful for informing sampling options for the second and third objectives.

Sampling of studies

A scoping review aims to map the literature on a particular topic rather than to provide an exhaustive explanation of a particular phenomenon of interest.[19][22] Thus, the number of included studies was expected to be high in the scoping reviews. To manage the high numbers for a scoping review such as this one (where the aim was to provide definitions and concepts), it was necessary to make use of a qualitative sampling approach. A qualitative sampling approach for this review aimed for variation and depth rather than an exhaustive sample; reviewing too large a number of studies can impair the quality of the analysis and synthesis.[23] We used two types of purposive sampling techniques called maximum variation sampling and theoretical sampling.[24] These techniques were used to identify both the range, variation, and similarities or differences in definitions and concepts and intervention descriptions (as per the second objective), and to provide a rich synthesis of explanations of causal relationships between DH and health management decision-making (as per the third objective). For the first objective, we did not apply a sampling strategy. Thus, we included all the studies that at a minimum provided a definition or description of a DH intervention.

Data extraction

BS extracted data for the first objective from all the included studies (n = 181). AH independently extracted data from 81 (45%) of included studies to verify data extraction done by the first reviewer. We used an MS Excel spreadsheet for data extraction, as presented in Figure 1. AH and BS extracted a few studies before clarifying the items in the spreadsheet. Once data extraction was complete, the reviewers were able to filter according to the individual items extracted in order to synthesize and compare the studies. Given the objectives of the scoping review, we did not extract any information relevant to conducting risk of bias or quality assessment. Not conducting risk of bias or quality assessment is consistent with scoping reviews of similar aims and methodological approaches.[19][22][25]

|

Data synthesis: Collating, summarizing, and reporting findings

The first reviewer (BS) conducted data analysis using manual coding and the filter option in MS Excel. Another reviewer (NL) reviewed the data analysis work on an ongoing basis as an additional quality check. For the first objective, we conducted a numerical analysis to provide an overview of the characteristics of all the included studies. For the second objective, we conducted a qualitative analysis to provide a narrative synthesis of the different DH definitions and concepts, and to identify different components or activities that are considered part of the DH processes. For the third objective, we reviewed data related to intentions, suggestions, and/or explanations of how DH may lead to improved health management decision-making. We extracted and analyzed data relevant to the second and third objectives at the same time. We first created a list of all the different terms used to describe DH interventions and then compared definitions across alternative terms by looking for similarities or differences in the definitions or descriptions of DH interventions. We then coded key components, processes, and outcomes of DH interventions and the factors reported as important in the relationship between DH and health management decision-making.

The findings are structured according to three themes matching the three study objectives: an overview of the key characteristics of included studies, alternative terms and definitions of DH, and a narrative synthesis of the relationship between DH and health management decision-making.

Reflexivity

Throughout the review, the authors were aware of their own positions and reflected on how these could influence the study design, search strategy, inclusion decisions, data extraction, and analysis, as well as the synthesis and interpretation of the findings.[23] The review authors are trained in anthropology, epidemiology, health systems, and evidence synthesis research. The first author was involved in participant observation of an innovative DH project in the Western Cape Department of Health in South Africa as part of her doctoral research, where she grappled with questions that informed the objectives of this review. Three of the authors (BS, AH, and NL) were involved in a Cochrane Collaboration systematic review on RHIS interventions when this scoping review was conceptualized, so they were familiar with some of the health information systems (HIS) literature and had some appreciation for the conceptual and methodological complexities of studying the field of health information management. This experience informed the way the first author developed the search strategy. She used an iterative approach to narrow down the search as much as possible because of her prior knowledge that it was difficult to balance sensitivity and specificity when developing a search strategy for HIS literature that is often multi-disciplinary in nature.

Results

Results of the search

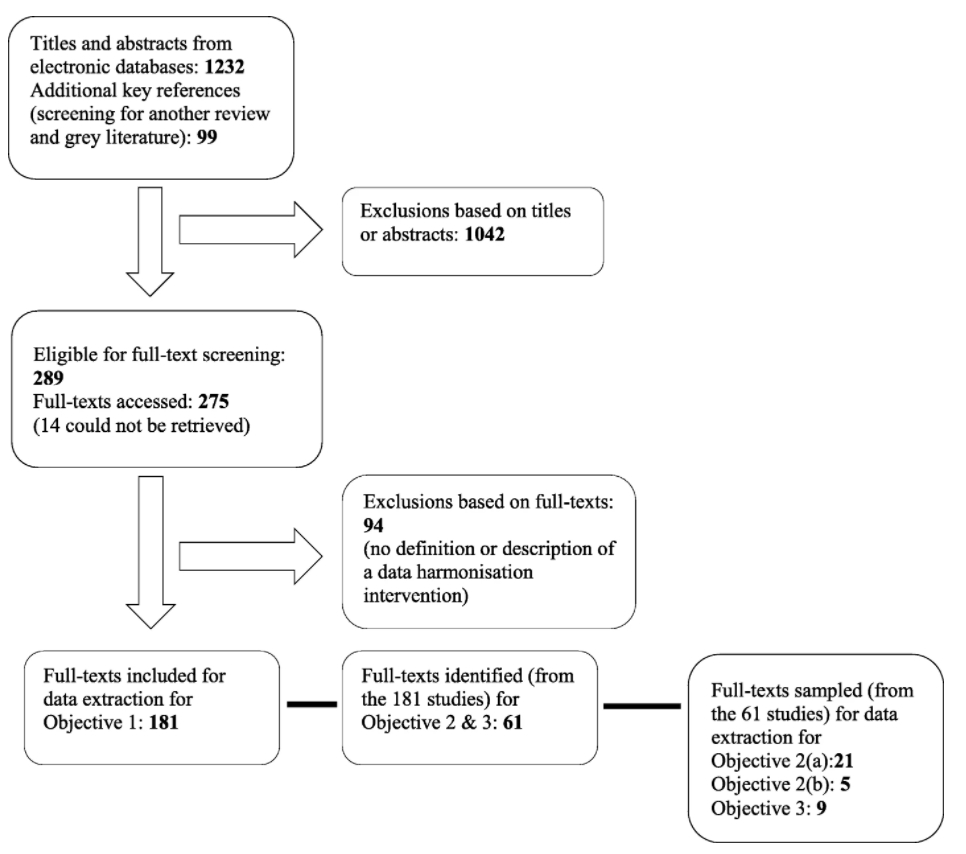

Figure 2 shows a PRISMA diagram of the search results. We screened a total of 1,331 records: 1,232 titles and abstracts identified from searching three electronic databases, and 99 from screening for a Cochrane Collaboration systematic review assessing the effectiveness of RHIS interventions on health systems management[26], as well as gray literature. Almost a quarter (289 of 1,331) were deemed potentially eligible for full-text screening. We accessed full-texts for 275 studies, and of those, 181 were included in the scoping review for the first objective. We excluded 94 full-text articles because they did not meet the minimum criteria; that is, they did not provide a definition or description of a DH intervention or activity. We sampled 61 studies from the 181 for the second and third objectives. We arrived at 61 studies by including all reviews (systematic or literature reviews) and all studies (irrespective of the type of study) that also had a process description, conceptual framework, or a theory of a DH intervention (that is, in addition to the minimum criteria for the first objective).

|

An overview of key characteristics of data harmonization studies

A total of 181 studies were included into this scoping review for the first objective (see Table 1). Given the high number of included studies, we decided to only map the following key characteristics of those studies: first author, date, type of study, intervention term (DH or alternative), country, and level of the health care system. Most included studies (126 of 181) were either primary studies assessing various aspects of developing and implementing DH interventions (quantitative studies n = 86), or patient, providers, or stakeholders’ perspectives (qualitative studies n = 34), or a combination of both (mixed methods studies n = 6).

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Of the 181 included studies, nine were not country-specific (these were global reviews), 151 were from the USA, and the rest were from other countries (specifically Australia, Brazil, Canada, China, Finland, Germany, Israel, Japan, Jordan, Korea, Malaysia, Netherlands, South Africa, and South Korea). In terms of the level of the health care system, 128 studies were on a DH intervention or activity that was concerned with the frontline level (health service providers), 48 studies were concerned with health system factors or policy-related activities at the managerial level, and five studies focused on DH interventions specifically for research purposes. Most studies (92%) used the term health information exchange (HIE), while the remaining studies (8%) used a variety of terms to describe various DH interventions and activities, specifically, record linkage, data mining, data linkage, data warehousing, data sharing, and data harmonization.

Definitions, components, and processes of data harmonization

In this subsection, we first discuss the alternative terms and definitions of DH, and then we summarize key components and processes of DH using studies sampled from the 61 studies identified for the second and third objectives. Table 2 presents identifying details of the 61 studies, including the type of study design, the intervention terms, the country, the level of the health care system, and the purpose of the study. These studies were concerned with the challenges and opportunities of DH, the barriers and facilitators of DH, the various factors affecting DH (such as technical and financial factors), the outcomes of DH (such as patient safety and quality of care), and the privacy and security issues of patient information.

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Alternative terms and definitions of data harmonization

For the second objective, we describe alternative terms and definitions of DH. We sampled 21 studies from the 61 studies identified for objectives two and three. The alternative terms and definitions are summarized in Table 3. During data analysis we realized that most studies (53 of 61) used the term "health information exchange," with similar definitions. We sampled 13 of the 53 studies to contribute to the composite HIE definition. These 13 studies were chosen to represent the term HIE because they were review studies, and we assumed that reviews provided synthesized definitions of interventions. Using maximum variation sampling, we included eight more studies (21 studies in total; see Table 3), because they provided a range of different terms for DH activities, besides the term HIE.

| ||||||||||||||||||

There is overlap between the terms and definitions. Definitions for data harmonization, record linkage, and data warehousing explicitly state that these interventions involve a process of having to integrate different or "homogeneous" databases or information systems. Data linkage and record linkage both focus on "linkage" as a core activity in combining different databases using a unique patient identifier. HIE is described as a key outcome of data interoperability, that is, where the focus is on technical linkage of different electronic databases. Data sharing, where the focus is on data accessibility and use, is described as a key outcome of HIE.

Based on the literature, we identified elements found in the various definitions of data harmonization. DH is considered a multi-step process with a range of activities (such as identifying, reviewing, matching, redefining, and standardizing information). Data harmonization interventions rely on interoperability between databases and systems, which means copying standardized patient-level data into a separate repository. Data linkage and record linkage are activities of a broader intervention (data harmonization), using mechanisms (such as unique patient identifiers) for integrating large datasets. Data warehousing is concerned with extracting, transforming, and loading large datasets using information technology (IT) platforms, application systems, and data displays (data marts or data dashboards). Data sharing (through the accessing and exchanging of electronic health information), can be considered an outcome of HIE interventions. The aim of these interventions is to integrate and make data accessible across different platforms (such as clinical and financial systems), and to allow for the sharing of this data across the patient care trajectory. The ultimate aim of DH, it would seem, is to improve patient outcomes, the coordination of health services, quality of care, and efficiency while facilitating public health interventions.

In reviewing the definitions, we identified nine characteristics of DH. No single study included all these characteristics, and there are no specific factors such as study design, country, or level of the health care system associated with the definitions. DH is characterized by the following characteristics:

- Any type of DH intervention or activity is a process of multiple steps involving both technical and social processes.

- The goal of a DH intervention or activity is to integrate, harmonize, and bring together different electronic databases into useable formats.

- There are at least two or more databases involved in any DH intervention or activity.

- A data harmonization intervention or activity involves electronic data (no reference is made to data found in paper-based sources).

- Data harmonization occurs when there is an increasing availability of electronic data that can be pooled together using unique patient identifiers.

- Different types of data can be linked and shared, such as individual patient clinical, pharmacy, and laboratory data; health care utilization and cost data; and personnel-related data.

- Electronic data required for DH processes can be found within and across different departments and institutions at facility, district, regional, and national levels.

- A data harmonization process consists of different types of technical activities such as identifying, reviewing, matching, defining, redefining, standardizing, merging, linking, merging, and formatting data.

- DH interventions or activities are defined according to a specific scope and purpose such as disease surveillance, monitoring of long-term outcomes, screening for adverse events, geographic area, secondary data use, and data display mechanisms (data marts or dashboards).

Components and processes of data harmonization

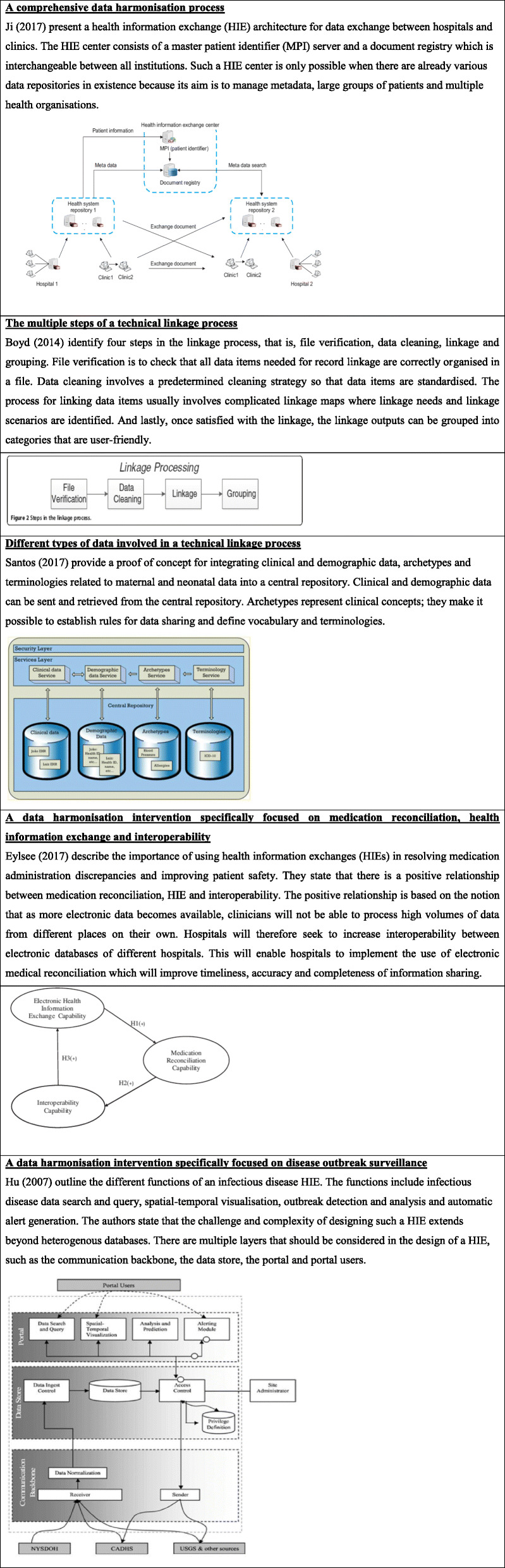

To synthesize key components and processes of DH interventions (second objective) we sampled five from the 61 studies identified for the second and third objectives. We selected five studies[16][17][28][41][42] based on the conceptual descriptions and visual illustrations of their DH interventions (see Figure 3).

|

The conceptual description by Ji et al.[41] comes closest to a comprehensive conceptual model of a DH intervention, illustrating different types of data, different levels of the health care system (e.g., clinics and hospitals), the multiple processes of exchanging data, the multiple directions in data exchange, and the key role of the unique patient identifier in enabling the DH process.[41] In the next model, Boyd et al.[16] and Santos et al.[42] both lay out the technical processes involved in the linkage of different databases, but Santos et al. specifically focuses on linking data required for individual patient clinical management into a central repository. Lastly, Elysee et al.[28] and Hu et al.[17] describe DH interventions with different purposes, that is, medication reconciliation and disease outbreak surveillance, respectively.

These conceptual models of DH interventions and activities highlight that there are various steps involved in the integration of databases and in the transformation of data into useable formats. Integrating databases means bringing together data of the same individual from within and between different electronic databases, through various activities involving identifying, reviewing, matching, redefining and standardizing data.[1][16] Once data is harmonized, it can be categorized by various criteria of interest, such as geographic area, disease, or patient population, and transformed into different formats such as graphs, tables, or dashboards to make it easier for users to access and use the information.[27] There may be different ways that the data is harmonized; in some studies, DH was described as a linear and one-directional process, while other studies described it as an iterative and multi-directional process.

The relationship between data harmonization and health management decision-making

We sampled nine studies from the 61 studies (identified for the second and third objectives) that provide an explanation of the relationship between DH and health management decision-making. These nine studies were selected because they referred to the intended benefit, or directly referred to the relationship between DH and health management decision-making. We present extracts of explanations of the relationship in Table 4.

| ||||||||||||||||||||||

According to Eylsee et al.[28] (the study providing the most detail), there is a positive relationship between increased availability of electronic data sets and the ability of clinicians to deal with high volumes of data. This necessitates interoperability between electronic databases at different hospitals in order to improve timeliness, accuracy, and completeness of information sharing. According to Ji et al.[41], Boyd et al.[16], Santos et al.[42], and Hu et al.[17], the main benefit of DH is health management decision-making, including clinical decision-making. Across the studies, there is agreement that DH interventions make it possible for health providers to use data over time and across organizations to support clinical management decision-making. There is acknowledgement that DH interventions were sometimes unable to deal effectively with inconsistencies, incompleteness, and poor quality of data.

From the nine studies in Table 4, we identified three types of health management decision-making that DH contributed to. These are:

- clinical decision-making for individual patient clinical management or clinical support and quality improvement tools;

- pperational and strategic decision-making for health system managers and policy-makers; and

- population-level decision-making for disease surveillance and outbreak management.

The first level involves frontline clinicians being able to access their patients’ medical information, treatment data, and timelines (datasets of longitudinal, clinically relevant individual-level data) through DH interventions. In these situations, DH can make it easier for frontline clinicians to develop tools for reminding them about patients’ performance in treatment and care services, as well as help them improve the quality of health care services. At the operational and strategic decision-making level, DH interventions have the potential to support high-level health managers in decision-making involving a wide network of stakeholders (consumers, patients, and professionals). Lastly, disease surveillance and outbreak management decision-making rely on harmonized data to plan, monitor, and evaluate population-level interventions.

Discussion

Synthesis of findings

This scoping review aimed to provide an overview of the key characteristics of DH studies; identify definitions, alternative terms, components, and processes of DH interventions; and provide explanations of the relationship between DH and health management decision-making. Of the 181 studies that at a minimum provided a definition or description of a DH intervention or activity, 86 were primary quantitative studies, 151 were studies conducted in the USA, and 128 were aimed at improving frontline-level health services.

A key finding is that the term "health information exchange" or HIE was the most frequently used in the literature, especially for studies for the USA. Other terms used were "data harmonization," "record linkage," "data linkage," "data warehousing," "data sharing," and "data interoperability." Terms like "data harmonization" and "data warehousing" seem to describe a more comprehensive approach to DH interventions (involving both data production and data utilization aspects), whereas terms like "record linkage" and "data linkage" described specific activities within health information exchange. The term "data interoperability" focuses on the technical aspects that allow for different electronic databases to be linked and for data to be integrated, which then allow for synthesis and analysis of health information. Even though different studies used different terms, there was consensus that DH is a useful tool for health management decision making and can support improvements in patient and health system outcomes.

We identified nine characteristics of DH interventions and activities. Using these nine characteristics, DH can be summarized as a process that aims to integrate two or more electronic databases involving different types of data captured within and across various institutions at different health care system levels, with varying activities required to pool together data using unique patient identifiers for the purpose of providing information support for health management decision-making. The review identified three types of health management decision-making that DH contributes to: (a) clinical decision-making for individual patient management, clinical support, and quality improvement tools; (b) operational and strategic decision-making for health system managers and policy-makers; and (c) population-level decision-making for disease surveillance and outbreak management.

Drawing on the definitions and the conceptual models of DH identified in this review, we developed a concept map (see Figure 4) to explain how different aspects of DH interventions and activities work together to support health management decision-making. The concept map consists of different types of databases (1 to 5) containing different types of data such as demographic, clinical, pharmacy, laboratory, administrative, financial, and terminology data. A technical process involving different types of activities (such as matching, merging, and linking) takes place to integrate the different types of data using a unique patient identifier. The central repository, where the data is harmonized, is defined according to specific criteria such as a geographic area or disease outcomes. The data kept in the repository should be accessible to data users, who can then use this harmonized data as an information and analytic tool to support health management decision-making for clinical, operational, strategic, and or population-level decision-making.

|

Study limitations

There are two main differences between the published protocol and this scoping review. We did not search the Global Health database as planned; we realized too late that none of the reviewers had permissions to access the database, and gaining access was not affordable. We did however manage to search at least three electronic databases, as is the convention in reviews.[23] Due to the large volume of studies included for full-text screening, it was not feasible to conduct the full text screening in duplicate as planned. The first reviewer (BS) assessed all full-texts, and then the second reviewer (AH) verified the decisions of the first reviewer in a third of the included studies, which allowed for additional quality checks.

There are two main limitations of the review. Firstly, we restricted our literature search to English. We did not have the resources required for reviewing non-English studies. Most studies identified were from the USA, but it is possible that studies from other non-English speaking, high-income countries with extensive electronic health systems (such as France) may have been missed. Secondly, although sampling aimed to identify variety, comprehensiveness, and meaningfulness of the definitions and explanations, there is a possibility that due to sampling, we may have missed relevant studies for the second and third objectives.

Implications for research and practice

There is a need to understand what DH interventions and activities are comprised of in diverse settings and contexts, especially in LMICs. There were fewer studies from LMICs, which may be due to a lower prevalence of electronic health information systems in those settings. Nevertheless, DH interventions hold promise for improving the informational support in LMICs; studies in these contexts could usefully expand the evidence base.

The review highlights the importance of providing detailed descriptions of DH interventions, to allow for better comparisons and to improve the transferability of study results. Additionally, many resources are spent on the technical development of DH projects, with the implicit assumption that this will provide the informational and analytic support for health management decision-making, but this assumption is seldom tested in the research. There is a need for qualitative research on the health system factors of implementing DH and for formative work to inform design of DH interventions. Finally, primary research and evidence synthesis of the experiences of key stakeholders involved (implementers and users of harmonized data) would improve our understanding of the causal mechanisms between data harmonization and health systems strengthening.

Conclusion

This review aimed to widen our understanding about the range of definitions, components, and processes of DH interventions, and how it can contribute to health management decision-making. Most studies of DH interventions and activities were conducted in high-income settings and used the term "health information exchange." The review described the processes, technical activities, types of data, mechanisms for integrating data, and purpose of the DH interventions. DH interventions contributed to three types of health management decision-making, that is, clinical decision-making, operational and strategic decision-making, and population-level surveillance decision-making. We have provided a concept map of the components of DH and have made recommendations for future research.

Abbreviations

CDE: clinical data exchange

CIE: clinical information exchange

DH: data harmonization

DL: data linkage

DS: data sharing

DW: data warehouse

EHR: electronic health record

HDE: health data exchange

HIE: health information exchange

HIS: health information system

IE: information exchange

IO: interoperability

IT: information technology

LMICs: low-to-middle-income countries

MeSH: Medical Subject Headings

RHISs: routine health information systems

RL: record linkage

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Ms. Gill Morgan, University of Cape Town, who assisted with developing the search strategy.

Contributions

BS was involved in all the tasks of conducting the scoping review. She drafted the manuscript with help from CC and NL. AH contributed to searching, screening, and data extraction processes. All authors reviewed and approved the final manuscript before final submission for peer review.

Funding

Time to write this paper was supported by the U.S. National Institute of Mental Health [grant number 1R01 MH106600] and the South African Medical Research Council (SAMRC). The content of this paper is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the U.S. National Institutes of Health or the SAMRC.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 Liu, D.; Wang, X.; Pan, F. et al. (2010). "Harmonization of health data at national level: a pilot study in China". International Journal of Medical Informatics 79 (6): 450–8. doi:10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2010.03.002. PMID 20399139.

- ↑ Nutley, T.; Reynolds, H.W. (2013). "Improving the use of health data for health system strengthening". Global Health Action 6: 20001. doi:10.3402/gha.v6i0.20001. PMC PMC3573178. PMID 23406921. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3573178.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Lippeveld, T. (2001). "Routine health information systems: The glue of a unified health system". Keynote address at the Workshop on Issues and Innovation in Routine Health Information in Developing Countries. https://docplayer.net/3034875-Routine-health-information-systems-the-glue-of-a-unified-health-system.html.

- ↑ World Health Organization (2007). "Everybody's Business: Strengthening Health Systems to Improve Health Outcomes" (PDF). World Health Organization. pp. 44. ISBN 9789241596077. https://www.who.int/healthsystems/strategy/everybodys_business.pdf?ua=1.

- ↑ Health Metrics Network, World Health Organization (November 2012). "Country Health Information Systems Assessments: Overview and Lessons Learned - Working Paper 3" (PDF). World Health Organization. Archived from the original on 21 October 2014. https://web.archive.org/web/20141021202640/http://www.who.int/healthmetrics/resources/Working_Paper_3_HMN_Lessons_Learned.pdf.

- ↑ Heywood, A.; Boone, D. (February 2015). "Guidelines for Data Management Standards in Routine Health Information Systems". Measure Evaluation. pp. 93. https://www.measureevaluation.org/resources/publications/ms-15-99.

- ↑ Karuri, J.; Waiganjo, P.; Orwa, D. et al. (2014). "DHIS2: The Tool to Improve Health Data Demand and Use in Kenya". Journal of Health Informatics in Developing Countries 8 (1): 113. https://jhidc.org/index.php/jhidc/article/view/113.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Harrison, M.I.; Koppel, R.; Bar-Lev, S. (2007). "Unintended consequences of information technologies in health care--an interactive sociotechnical analysis". JAMIA 14 (5): 542–9. doi:10.1197/jamia.M2384. PMC PMC1975796. PMID 17600093. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1975796.

- ↑ van Olmen, J.; Criel, B.; Bhojani, U. et al. (2012). "The Health System Dynamics Framework: The introduction of an analytical model for health system analysis and its application to two case-studies". Health, Culture and Society 2 (1): 1–21. doi:10.5195/hcs.2012.71.

- ↑ Sittig, D.F.; Singh, H. (2010). "A new sociotechnical model for studying health information technology in complex adaptive healthcare systems". Quality & Safety in Healthcare 19 (Suppl. 3): i68–74. doi:10.1136/qshc.2010.042085. PMC PMC3120130. PMID 20959322. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3120130.

- ↑ Plsek, P. (27 January 2003). "Complexity and the Adoption of Innovation in Health Care" (PDF). Accelerating Quality Improvement in Health Care Strategies to Speed the Diffusion of Evidence-Based Innovations. https://www.nihcm.org/pdf/Plsek.pdf.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 Cresswell, K.M.; Sheikh, A. (2014). "Undertaking sociotechnical evaluations of health information technologies". Informatics in Primary Care 21 (2): 78–83. doi:10.14236/jhi.v21i2.54. PMID 24841408.

- ↑ Cresswell, K.M.; Bates, D.W.; Sheikh, A. (2017). "Ten key considerations for the successful optimization of large-scale health information technology". JAMIA 24 (1): 182–7. doi:10.1093/jamia/ocw037. PMID 27107441.

- ↑ Fichtinger, A.; Rix, J.; Schäffler, U. et al. (2011). "Data Harmonisation Put into Practice by the HUMBOLDT Project". International Journal of Spatial Data Infrastructures Research 6: 234–60. doi:10.2902/1725-0463.2011.06.art11.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 Akhlaq, A.; McKinstry, B.; Muhammad, K.B.; Sheikh, A. (2016). "Barriers and facilitators to health information exchange in low- and middle-income country settings: A systematic review". Health Policy and Planning 31 (9): 1310–25. doi:10.1093/heapol/czw056. PMID 27185528.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 16.2 16.3 16.4 16.5 Boyd, J.H.; Randall, S.M.; Ferrante, A.M. et al. (2014). "Technical challenges of providing record linkage services for research". BMC Medical Informatics and Decision Making 14: 23. doi:10.1186/1472-6947-14-23. PMC PMC3996173. PMID 24678656. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3996173.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 17.2 17.3 17.4 Hu, P.J.; Zeng, D.; Chen, H. et al. (2007). "System for infectious disease information sharing and analysis: Design and evaluation". IEEE Transactions on Information Technology in Biomedicine 11 (4): 483–92. doi:10.1109/titb.2007.893286. PMC PMC7186032. PMID 17674631. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7186032.

- ↑ Aqil, A.; Lippeveld, T.; Hozumi, D. (2009). "PRISM framework: A paradigm shift for designing, strengthening and evaluating routine health information systems". Health Policy and Planning 24 (3): 217–28. doi:10.1093/heapol/czp010. PMC PMC2670976. PMID 19304786. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2670976.

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 19.2 Arksey, H.; O'Malley, L. (2005). "Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework". International Journal of Social Research Methodology 8 (1): 19–32. doi:10.1080/1364557032000119616.

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 Schmidt, B.-M.; Colvin, C.J.; Hohlfeld, A. et al. (2009). "Defining and conceptualising data harmonisation: A scoping review protocol". Health Policy and Planning 7 (1): 226. doi:10.1186/s13643-018-0890-7. PMC PMC6284298. PMID 30522527. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6284298.

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 Cimino, J.J.; Frisse, M.E.; Halamka, J. et al. (2014). "Consumer-mediated health information exchanges: The 2012 ACMI debate". Journal of Biomedical Informatics 48: 5–15. doi:10.1016/j.jbi.2014.02.009. PMC PMC5514840. PMID 24561078. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5514840.

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 Tricco, A.C.; Lillie, E.; Zarin, W. et al. (2016). "A scoping review on the conduct and reporting of scoping reviews". BMC Medical Research Methodology 16: 15. doi:10.1186/s12874-016-0116-4. PMC PMC4746911. PMID 26857112. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4746911.

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 23.2 Glenton, C.; Paulsen, L.; Bohren, M. et al. (2017). "Qualitative Evidence Synthesis template". Effective Practice and Organisation of Care. The Cochrane Collaboration. https://epoc.cochrane.org/news/qualitative-evidence-synthesis-template.

- ↑ Suri, H. (2011). "Purposeful Sampling in Qualitative Research Synthesis". Qualitative Research Journal 11 (2): 63–75. doi:10.3316/QRJ1102063.

- ↑ Popay, J.; Roberts, H.; Sowden, A. et al. (April 2006). "Guidance on the Conduct of Narrative Synthesis in Systematic Reviews: A Product from the ESRC Methods Programme". Lancaster University. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/233866356_Guidance_on_the_conduct_of_narrative_synthesis_in_systematic_reviews_A_product_from_the_ESRC_Methods_Programme.

- ↑ Leon, N.; Brady, L.; Kwamie, A. et al. (2015). "Routine Health Information System (RHIS) interventions to improve health systems management". Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2015 (12): CD012012. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD012012.

- ↑ 27.0 27.1 Haarbrandt, B.; Tute, E.; Marschollek, M. (2016). "Automated population of an i2b2 clinical data warehouse from an openEHR-based data repository". Journal of Biomedical Informatics 63: 277-294. doi:10.1016/j.jbi.2016.08.007. PMID 27507090.

- ↑ 28.0 28.1 28.2 28.3 28.4 Elysee, G.; Herrin, J.; Horwitz, L.I. (2017). "An observational study of the relationship between meaningful use-based electronic health information exchange, interoperability, and medication reconciliation capabilities". Medicine 96 (41): e8274. doi:10.1097/MD.0000000000008274. PMID PMC5662321.

- ↑ Dixon, B.E.; Zafar, A.; Overhage, J.M. (2010). "A Framework for evaluating the costs, effort, and value of nationwide health information exchange". JAMIA 17 (3): 295–301. doi:10.1136/jamia.2009.000570. PMC PMC2995720. PMID 20442147. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2995720.

- ↑ Esmaeilzadeh, P.; Sambasivan, M. (2016). "Health Information Exchange (HIE): A literature review, assimilation pattern and a proposed classification for a new policy approach". Journal of Biomedical Informatics 64: 74–86. doi:10.1016/j.jbi.2016.09.011. PMID 27645322.

- ↑ Esmaeilzadeh, P.; Sambasivan, M. (2017). "Patients' support for health information exchange: A literature review and classification of key factors". BMC Medical Informatics and Decision Making 17 (1): 33. doi:10.1186/s12911-017-0436-2. PMC PMC5379518. PMID 28376785. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5379518.

- ↑ Fontaine, P.; Ross, S.E.; Zink, T. et al. (2010). "Systematic review of health information exchange in primary care practices". Journal of the American Board of Family Medicine 23 (5): 655–70. doi:10.3122/jabfm.2010.05.090192. PMID 20823361.

- ↑ Hopf, Y.M.; Bond, C.; Francis, J. et al. (2014). "Views of healthcare professionals to linkage of routinely collected healthcare data: A systematic literature review". JAMIA 21 (e1): e6–10. doi:10.1136/amiajnl-2012-001575. PMC PMC3957379. PMID 23715802. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3957379.

- ↑ Kash, B.A.; Baek, J.; Davis, E. et al. (2017). "Review of successful hospital readmission reduction strategies and the role of health information exchange". International Journal of Medical Informatics 104: 97–104. doi:10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2017.05.012. PMID 28599821.

- ↑ Mastebroek, M.; Naaldenberg, J.; Lagro-Janssen, A.L. et al. (2014). "Health information exchange in general practice care for people with intellectual disabilities--a qualitative review of the literature". Research in Developmental Disabilities 35 (9): 1978–87. doi:10.1016/j.ridd.2014.04.029. PMID 24864050.

- ↑ Parker, C.; Winer, M.; Reeves, M. et al. (2016). "Health information exchanges--Unfulfilled promise as a data source for clinical research". International Journal of Medical Informatics 87: 1–9. doi:10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2015.12.005. PMID 26806706.

- ↑ Rahurkar, S.; Vest, J.R.; Menachemi, N. (2015). "Despite the spread of health information exchange, there is little evidence of its impact on cost, use, and quality of care". Health Affairs 34 (3): 477–83. doi:10.1377/hlthaff.2014.0729. PMID 25732499.

- ↑ Rudin, R.S.; Motala, A.; Goldzweig, C.L. et al. (2014). "Usage and effect of health information exchange: A systematic review". Annals of Internal Medicine 161 (11): 803–11. doi:10.7326/M14-0877. PMID 25437408.

- ↑ Sadoughi, F.; Nasiri, S.; Ahmadi, H. (2018). "The impact of health information exchange on healthcare quality and cost-effectiveness: A systematic literature review". Computer Methods and Programs in Biomedicine 161: 209–32. doi:10.1016/j.cmpb.2018.04.023. PMID 29852963.

- ↑ Vest, J.R.; Jasperson, J.S. (2012). "How are health professionals using health information exchange systems? Measuring usage for evaluation and system improvement". Journal of Medical Systems 36 (5): 3195–204. doi:10.1007/s10916-011-9810-2. PMC PMC3402621. PMID 22127521. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3402621.

- ↑ 41.0 41.1 41.2 41.3 Ji, H.; Yoo, S.; Heo, E.-Y. et al. (2017). "Technology and Policy Challenges in the Adoption and Operation of Health Information Exchange Systems". Healthcare Informatics Research 23 (4): 314-321. doi:10.4258/hir.2017.23.4.314. PMC PMC5688031. PMID 29181241. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5688031.

- ↑ 42.0 42.1 42.2 Santos, M.R.; de Sá, T.Q.V.; da Silve, F.E. et al. (2017). "Health Information Exchange for Continuity of Maternal and Neonatal Care Supporting: A Proof-of-Concept Based on ISO Standard". Applied Clinical Informatics 8 (4): 1082-1094. doi:10.4338/ACI-2017-06-RA-0106. PMC PMC5802311. PMID 29241246. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5802311.

- ↑ Downs, S.M.; van Dyck, P.C.; Rinaldo, P. et al. (2010). "Improving newborn screening laboratory test ordering and result reporting using health information exchange". JAMIA 17 (1): 13–8. doi:10.1197/jamia.M3295. PMC PMC2995628. PMID 2006479. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2995628.

- ↑ Grossman, J.M.; Kushner, K.L.; November, E.A. (2008). "Creating sustainable local health information exchanges: Can barriers to stakeholder participation be overcome?". Research Brief (2): 1–12. PMID 18496926.

- ↑ Kuperman, G.J.; McGowan, J.J. (2013). "Potential unintended consequences of health information exchange". Journal of General Internal Medicine 28 (12): 1663–6. doi:10.1007/s11606-012-2313-0. PMC PMC3832705. PMID 23690236. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3832705.

- ↑ Politi, L.; Codish, S.; Sagy, I. et al. (2014). "Use patterns of health information exchange through a multidimensional lens: Conceptual framework and empirical validation". Journal of Biomedical Informatics 52: 212–21. doi:10.1016/j.jbi.2014.07.003. PMID 25034041.

- ↑ Vest, J.R.; Gamm, L.D. (2010). "Health information exchange: Persistent challenges and new strategies". JAMIA 17 (3): 288–94. doi:10.1136/jamia.2010.003673. PMC PMC2995716. PMID 20442146. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2995716.

- ↑ Shapiro, J.S.; Kannry, J.; Lipton, M. et al. (2006). "Approaches to patient health information exchange and their impact on emergency medicine". Annals of Emergency Medicine 48 (4): 426–32. doi:10.1016/j.annemergmed.2006.03.032. PMID 16997679.

- ↑ Vest, J.R.; Abramson, E. (2015). "Organizational Uses of Health Information Exchange to Change Cost and Utilization Outcomes: A Typology from a Multi-Site Qualitative Analysis". AMIA Annual Symposium Proceedings 2015: 1260–8. PMC PMC4765592. PMID 26958266. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4765592.

- ↑ Zaidan, B.B.; Haiqi, A.; Zaidan, A.A. et al. (2015). "A security framework for nationwide health information exchange based on telehealth strategy". Journal of Medical Systems 39 (5): 51. doi:10.1007/s10916-015-0235-1. PMID 25732083.

Notes

This presentation is faithful to the original, with only a few minor changes to presentation. In some cases important information was missing from the references, and that information was added. The "Study objectives" section in the original only states two objectives, leading to confusion when encountering references to three objectives; the intended three objectives were inferred from the rest of the text and restated for this version. The original tables didn't include an abbreviation key; the meaning of the abbreviations was inferred from the rest of the text (and the cited papers) and added for this version. Additionally, the author has been contacted asking for clarification. The original Table 4 was converted into Figure 3, bumping the existing Figure 3 to Figure 4 and making the original Table 5 into Table 4.