Journal:A security review of local government using NIST CSF: A case study

| Full article title | A security review of local government using NIST CSF: A case study |

|---|---|

| Journal | The Journal of Supercomputing |

| Author(s) | Ibrahim, Ahmed; Valli, Craig; McAteer, Ian; Chaudhry, Junaid |

| Author affiliation(s) | Edith Cowan University, Embry-Riddle Aeronautical University |

| Primary contact | Email: ahmed dot ibrahim at ecu dot edu dot au |

| Year published | 2018 |

| Volume and issue | 74(10) |

| Page(s) | 5171–86 |

| DOI | 10.1007/s11227-019-02972-w |

| ISSN | 1573-0484 |

| Distribution license | Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International |

| Website | https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s11227-018-2479-2 |

| Download | https://link.springer.com/content/pdf/10.1007%2Fs11227-018-2479-2.pdf (PDF) |

|

|

This article contains rendered mathematical formulae. You may require the TeX All the Things plugin for Chrome or the Native MathML add-on and fonts for Firefox if they don't render properly for you. |

Abstract

Evaluating cybersecurity risk is a challenging task regardless of an organization’s nature of business or size, yet it remains an essential activity. This paper uses the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) Cybersecurity Framework (CSF) to assess the cybersecurity posture of a local government organization in Western Australia. Our approach enabled the quantification of risks for specific NIST CSF core functions and respective categories and allowed making recommendations to address the gaps discovered to attain the desired level of compliance. This has led the organization to strategically target areas related to their people, processes, and technologies, thus mitigating current and future threats.

Keywords: NIST Cybersecurity Framework, local government, cybersecurity, risk assessment

Introduction

The National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) Cybersecurity Framework (CSF)[1] is a risk-based approach to manage risks organizations face from a cybersecurity perspective. Similarly, several frameworks such as NIST SP 800-53[2], COBIT5[3], ISO/IEC 27001:2013[4], ISA 62443-2-1:2009[5], and ISA 62443-3-3:2013[6] are being used to assess cybersecurity risk from different perspectives, and outcomes are measured using different yardsticks. Often, navigating the various frameworks can be challenging for organizations, especially if such expertise are not present internally. Given the rapidly changing technology and threat landscape, assessing the cybersecurity posture of an organization, regardless of their business or size, is paramount.

The main goals of this paper are:

- detailing the adoption of the NIST CSF as an assessment tool that targets different levels of the organization, depending on their level of expertise and job function to obtain responses to facilitate assessment;

- quantifying the assessment to reflect severity of actual risk, which in turn enables the organization to effectively address the issues to attain the desired level of compliance; and

- reviewing in detail similar frameworks used in the industry and relevant case studies.

The next section provides a background of the NIST CSF and its components. In tandem, we recommend the reader refer to NIST[1] for additional details and strategies for suitable approaches to implement, which would vary from organization to organization. From there, our focus for the paper shifts to demonstrating the application of NIST CSF in a local government organization and providing recommendations based on our findings.

The NIST CSF

The NIST CSF[1] consists of the Framework Core, the Framework Implementation Tiers, and the Framework Profiles. The Framework Core consists of five concurrent and continuous functions: identify, protect, detect, respond, and recover. We designed an assessment tool for our investigation based on these functions, which provided a systematic approach to ascertain the organizations cybersecurity risk management practices and processes.

The Framework Implementation Tiers describe the level that an organization's cybersecurity risk management practices comply with the framework. Tiers provide the context and degree to which cybersecurity risks are managed, as well as the extent to which business needs are considered in cybersecurity risk management. The assessment tool enabled the determination of the organization's Current Tier based on various internal and external factors such as their risk management practices, threat environment, legal and regulatory requirements, business/mission objectives, and organizational constraints. Organizations should also determine the desired tier, provided it is feasible to implement, reduces cybersecurity risks, and meets organizational goals. The following are descriptions of the tier levels[1]:

- Tier-1 (Partial): Risk management practices are not formalized and managed in an ad hoc manner, lack awareness of cybersecurity risks organization-wide, and do not have processes in place to collaborate with external entities.

- Tier-2 (Risk Informed): Risk management practices are formalized but not integrated organization-wide. Cybersecurity activities are prioritized based on risks, with adequate means to perform related duties, and with informal means to communicate cybersecurity information internally and externally.

- Tier-3 (Repeatable): Risk management practices are formalized and policies are in-place and adaptable to cyber threats. An organization-wide approach is required to manage cybersecurity, with skilled and knowledgeable personnel required to rapidly respond, understand dependencies, and understand the role of external partners.

- Tier-4 (Adaptive): Cybersecurity practices are based on lessons learned and predictive indicators, with continuous improvement, adaptability, and timely response. An organization-wide approach is required to manage cybersecurity risks. Cybersecurity is part of the organizational culture, and the organization actively shares with external partners.

The Framework Profile represents the outcomes based on the business needs the organization characterized from the Framework Core and determined using the assessment tool. Consequently, a "current profile" (the “as is” state) and a "target profile" (the “to be” state) can be used to identify opportunities for improving the cybersecurity of the organization.[1] Framework profiles can be determined based on particular implementation scenarios, and therefore, the gap between the current profile and the target profile would vary as per scenario. In this paper, a local government-specific approach to CSF was adapted. However, industry-specific tailoring may be performed for the CSF.

Methodology

The NIST CSF allowed us to design an assessment tool targeted at three levels of participants within the organization: executive, management, and technical. The rationale was to ascertain organization-wide understanding of cybersecurity risks. Hence, the assessment tool comprised of questions addressing the requirements outlined as per the NIST CSF.

The questions were selected based on the nature and relevance to the level of the participant. This is because the NIST CSF comprised of questions that were both technical and non-technical. Therefore, it would have been unrealistic to expect deep knowledge of technical operations or implementation level details from a policy level executive.

In order to assist us determine a baseline (i.e., the desired tier), additional questions were included in the assessment tool to determine the nature of the organization and its business. This was then followed by the remaining requirements comprised in the NIST CSF.

Determining compliance

The compliance for each measure was based on the responses provided by the participants. They were graded as complaint, partially compliant, or non-compliant, and each was assigned scores of either 10, 5, or 0, respectively, for each core function’s subcategory. Any subcategory that was not applicable based on the desired tier level was excluded from the compliance score calculation.

Given the number of security requirements for each core function’s subcategory is N, then the number of applicable requirements in each subcategory given the desired tier level is N′. Therefore, the total compliance score C for each core function’s category can be defined as:

where R is the compliance score for each category of the respective core function.

Additionally, a detailed document audit was conducted on existing policies and procedures. The information technology (IT) infrastructure (internal, remote locations, and cloud) were reviewed, and a detailed internal vulnerability assessment was also conducted during our investigation.

Findings

The responses provided by the executive, management, and technical participants gave insight into the organization’s cybersecurity posture. Table 1 shows the summary of the compliance of NIST CSF assessment. The compliance scores were determined based on the previously presented equation.

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

For the "identify" core function, the organization scored 36%. Their ability to track assets centrally, keep management informed, and understand operational risks from a cybersecurity perspective was limited, while a strategy to manage such risks did not exist. However, the organization understood its business well and was able to set priorities to support risk management decisions.

Access to physical/virtual assets were through authorization and well-defined processes. The staff were trained and informed adequately of information security-related duties and responsibilities. Certain aspects of data security related to confidentiality and availability were done reasonably well; however, assuring integrity of data needed improvement. Similarly, local maintenance and remote maintenance of IT infrastructure were carried out in a manner consistent to policies and procedures. However, relevant policies, processes, and procedures, as well as technology to assist the protection of information systems and relevant assets, were lacking. Therefore, in aggregate, the organization scored 45% compliance for the "protect" core function.

The organization scored weakest in the detection of cybersecurity incidents, with a score of 25%. Although certain monitoring activities were in place to track physical security and malicious code, timely detection of anomalous activities and detection processes were lacking or non-existent.

Despite the lack of a specific response plan to respond to cybersecurity events, the organization had measures in place to report incidents and coordinate activities to respond adequately, which resulted in a 38% compliance score for the "respond" core function. These practices are updated from time to time; however, mechanism to perform post-incident analysis or to mitigate future cybersecurity events has not been implemented presently.

Interestingly, the organization was well prepared to deal with recovery and resumption of core services after a cybersecurity event. The recovery plans in place are tested, updated, and improved periodically, thus receiving full compliance for the "recover" core functionality of the framework.

Recommendations

Based on the findings, the following recommendations were made with respect to each core function of the NIST CSF.

Identify

- (a) Establish a central inventory of assets, including physical devices and systems, software, and external systems, with all required information, and prioritize based on classification, criticality, and business value.

- (b) Identify the organizations role in the supply chain (i.e., producer-consumer model) as it captures and retains public data, collects revenue, and provides services to its stakeholders.

- (c) Establish an information security policy and reference relevant federal and state policies regarding cybersecurity to ensure legal and regulatory requirements are understood and managed.

- (d) Identify and prioritize threats and vulnerabilities, both internal and external, to determine cybersecurity risks to the organization's operations, assets, and individuals.

- (e) Establish risk management processes that are managed and agreed to by stakeholders to support operational risk decisions.

Protect

- (a) Strengthen the access control policy and procedures for organization-wide assets that require both physical and remote access.

- (b) Sensitize and increase awareness about cybersecurity throughout the workforce more comprehensively, and provide adequate cybersecurity training based on roles and responsibilities. In this regard, clearly describe cybersecurity roles and responsibilities for relevant staff and external stakeholders.

- (c) Enforce required provisions for data security in the policy, and implement data-at-rest and data-in-transit security, as well as integrity-checking mechanisms to ensure confidentiality, integrity, and availability of information and data.

- (d) Establish required policies, processes, and procedures to manage protection of information assets. This include the establishment of lacking policies and processes, particularly for configuration management, data destruction, and physical operating environment; identification of security baselines; SDLC for system management; and formulation of vulnerability, response, and recovery plans.

- (e) Strengthen processes that control and log remote access to organizational assets by external maintenance contractors.

- (f) Establish a central log of organization-wide information systems and devices, establish removable media policy, and strengthen network segregation to protect communication and control networks.

Detect

- (a) Determine baselines for network operations and data flows, and implement appropriate activities to detect and analyze events based on event data aggregated from multiple sources and sensors. Determine incident impact and threshold to prepare and allocate resources appropriately.

- (b) Implement tools to monitor cyber and physical environments to detect unauthorized mobile code, external service provider activities, and unauthorized access. Perform organization-wide vulnerabilities regularly.

- (c) Outline detection requirements in information security policy, and continuously improve these processes to ensure timely and adequate awareness of anomalous events.

Respond

- (a) Establish processes and procedures to respond to cybersecurity events in a timely manner.

- (b) Define cybersecurity roles and responsibilities in information security policy to ensure activities are coordinated for internal and external stakeholders, including law enforcement, in response to cybersecurity events.

- (c) Implement required cybersecurity event notification and detection systems to ensure adequate information is available to analyze and understand the impact to support recovery activities.

- (d) Implement required cybersecurity controls to detect, report, and contain incidents to prevent escalation of an incident, mitigate its effect, and eradicate the incidents.

Discussing the recommendations

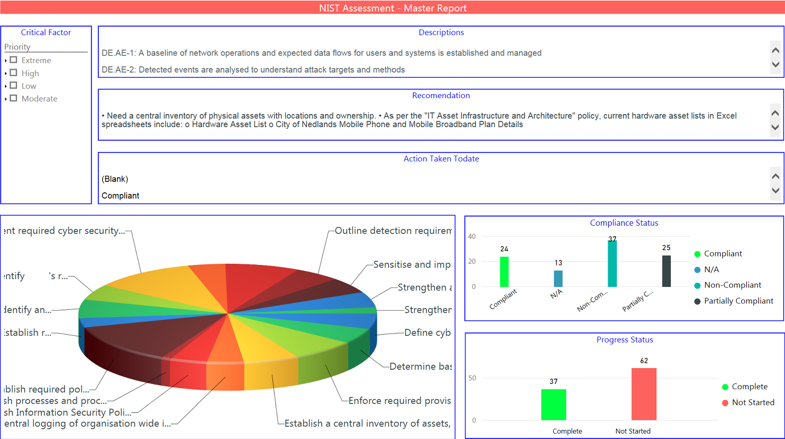

Each of the above recommendations also had specific internal stakeholder(s) identified to indicate ownership and responsibility for addressing the issues associated. Consequently, the organization was then able to develop strategies to address the issues identified and assign specific tasks to individuals. For this purpose, the organization established an internal document using Microsoft Power BI[7] (typically referred to as a Power BI site) to track and visualize the status of the NIST CSF assessment (Fig. 1).

|

The Power BI site facilitated transparency, visibility, and central reporting throughout the organization. Intuitively, this resulted in a rapid and responsive drive for the organization to address and prioritize issues based on severity and cost, with the goal of achieving Tier-2 compliance.

Furthermore, a desire to achieve a higher compliance level such as Tier-3 was expressed. Such aspiration is encouraged, however, with caution. Even though a higher level of compliance will improve the cybersecurity posture of the organization, it will also affect other aspects such as resources and cost. For example, contrast the risk management process between Tier-2 and Tier-3 as defined in the NIST CSF[1]:

- (a) Implementation of risk management practices are not mandatory in Tier-2, whereas these have to be implemented as organization-wide policies in Tier-3. Thus, Tier-3 organizations should have the procedures, processes, technology, and human resources to implement relevant policies.

- (b) The cybersecurity activities’ priorities are updated in a passive nature in Tier-2 as opposed to regular active updates and constant re-evaluation of priorities for Tier-3 compliance. To acquire such capability, an organization requires adequate technology, skilled human resources, and relevant policies that would enable keeping pace with the changes in the technology and threat landscape.

In addition to the two points highlighted above, considering both the integrated risk management program and external participation[1], significant investment in resources and human skills development or acquisition is needed to make the transition from Tier-2 to Tier-3. Moreover, this should only be considered carefully based on the organization’s business requirements, strategic objectives, budget, risk appetite, and current and future threats.

Related frameworks

The diversity and complexity of information technology (IT) system components have increased significantly in recent years. Consequently, in order for businesses to adequately secure these systems, several standards and frameworks have been developed.[8] Such frameworks need to be applicable to all manner of business sectors, be they government or private, enterprise or small-business.

Since NIST CSF can be considered a high-level abstraction of related frameworks, it provides references to other related frameworks for specific implementation guidelines. These referenced frameworks include:

- NIST SP 800-53 Rev. 4

- Control Objectives for Information and Related Technologies (COBIT5)

- ISO/IEC 27001:2013

- ISA 62443-2-1:2009

- ISA 62443-3-3:2013

These are further described below.

NIST SP 800-53 Rev. 4

NIST SP 800-53[2] revisions are made according to changes in responsibilities under the Federal Information Security Management Act (FISMA), Public Law (P.L.) 107-347. Revision 4 of this framework consists of five functions (identify, protect, detect, respond, and recover), 22 categories, and 98 subcategories. This framework utilizes a four-tier security model (partial, risk informed, repeatable, and adaptive) and a seven-step process (prioritize and scope, orient, create a current profile, conduct a risk assessment, create a target profile, determine, analyze and prioritize gaps, and implement action plan). It focuses on assessing the current situation by determining how to assess security, how to consider risk, and how to resolve the security threats.

Table 2 provides a summary of useful examples of how the NIST SP 800-53 framework has been applied in practice.

| ||||||||||||||||

Control Objectives for Information and Related Technologies (COBIT5)

COBIT5[3] is a business CSF designed for the governance and maintenance of enterprise IT systems. It consists of five domains and 37 processes in-line with the responsibility areas of plan, build, run, and monitor. COBIT5 is aligned and coordinated with other recognized IT standards and good practices, such as NIST, ISO 27000, COSO, ITIL, BiSL, CMMI, TOGAF, and PMBOK. It is built around the following considerations:

- meeting stakeholder expectations.

- controlling enterprise process end-to-end

- working as a single integrated framework

- recognizing that “management” and “governance” are two different things

ISO/IEC 27001:2013

ISO/IEC 27001:2013[4] is an international information security standard published by the International Organization for Standardization (ISO) and the International Electrotechnical Commission (IEC), which originated from the British Standard, BS 7799. This framework consists of 114 controls in 14 groups describing the requirements needed to design and implement an information security management system (ISMS). Version 2, released in 2013, replaces the original 2005 version. It is a standard that should be implemented by all businesses where information security is a critical factor, but in particular, applies to software development, managed service providers/hosting services providers, IT, banking and insurance, information management, government agencies and their service providers, and e-commerce merchants.[4]

Table 3 provides a summary of useful examples of how the ISO/IEC 27001:2013 framework has been applied in practice.

| ||||||||||||||||||

ISA 62443-2-1:2009

ISA 62443-2-1:2009[5] is an International Standards on Auditing (ISA) standard covering the elements required to develop an industrial automation control system - security management system (IACS-SMS). It consists of three categories, three element groups, and 22 elements. The framework is the first of four ISA policy and procedure products that identifies the essentials necessary to establish an effective cybersecurity management system (CSMS). However, the step-by-step approach as to how this is achieved is company-specific and according to their own business culture. These essentials addressed by this standard include:

- analyzing risk

- addressing risk with the CSMS

- monitoring and improving the CSMS

ISA 62443-3-3:2013

ISA 62443-3-3:2013[6] is an International Standards on Auditing (ISA) standard covering the elements required for cybersecurity controls of industrial control systems (ICS). It consists of seven foundation requirements and 51 system requirements.

ISA 62443-3-3:2013 is the third of three ISA systems products that outlines system security requirements and security levels.[6]

Other frameworks

In addition to the above, other frameworks used in the industry include the following:

- The Committee of Sponsoring Organizations of the Treadway Commission's (COSO) Enterprise Risk Management standard is designed jointly by five leading associations, with the aim of integrating strategy and performance.[22]

- The Council on CyberSecurity (now Center for Internet Security) CIS Controls consist of a prioritized set of actions, originally developed by the SANS Institute, to protect assets from cyber attack.[23]

- ISF Standard of Good Practice for Information Security is a standard aimed at providing controls and guidance on all aspects of information security.[24]

- ETSI Cyber Security Technical Committee (TC Cyber) was developed to improve standards within the European telecommunications sector.[25]

- The Sherwood Applied Business Security Architecture (SABSA) Enhanced NIST Cybersecurity (SENC) project enhances the five core levels of the NIST CSF into a SABSA model consisting of a six-level security architecture.[26]

- The IASME Consortium's Cyber Essentials is an information assurance standard based on ISO 27000 but aimed at small businesses.[27]

- The IETF's RFC 2196 Site Security Handbook represents a guide on how to develop computer security policies and procedures.[28]

- Health Information Trust Alliance's HITRUST CSF is the first IT security CSF designed specifically for the healthcare sector. It is based on existing NIST standards and is aimed at healthcare and information security professionals.[29]

- North American Electric Reliability Corporation Critical Infrastructure Protection (NERC-CIP), Version 5 is a set of requirements needed to secure the assets of the North American bulk electric system.[30]

- Open Security Architecture (OSA) is a free community-owned resource of advice on the selection, design, and integration of devices required to provide security and control of an IT network.[31]

- Good Practice Guide 13 (GPG13) is a U.K. government CSF related to Code of Connection (CoCo) compliance for businesses to secure IT systems.[32]

Conclusion

In this paper we have used the NIST CSF to evaluate the cybersecurity risks of a local government organization in Western Australia. Our approach can be used to derive measurable metrics for each Framework Core function and respective categories, thus enabling the organization to ascertain the cybersecurity preparedness to actual risk.

Our findings suggest that evaluating the desired tier compliance to the NIST CSF helps identify the specific people, processes, and technology areas that require improvement (i.e., gaps), which directly influence threat mitigation. The application of CSF helped us understand the current security context of the organization while identifying the risks and future growth areas to improve. While higher tier compliance may be desired, we have also recommended that the organization’s business requirements, strategic goals, budget, risk appetite, and current and future threats be considered carefully.

Furthermore, as we have presented several related frameworks, navigating such frameworks for self-assessment can be challenging—often not intended by design—but not impossible. We have observed that the NIST CSF offers an advantage over other frameworks in this regard. However, there is still room for developing additional tools that would simplify the implementation process and speed up adoption.

Therefore, our future work will aim to improve the current assessment tool we have used, with a focus of making it adaptable and accessible to a wider audience and measurable for accurate quantification of cyber preparedness.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the Western Australia local government organization for sharing their case study for this research. We would also like to thank their staff for their support and cooperation during the assessment.

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 1.6 National Institute of Standards and Technology. "Cybersecurity Framework". https://www.nist.gov/cyberframework.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 National Institute of Standards and Technology (December 2014). "Assessing Security and Privacy Controls in Federal Information Systems and Organizations" (PDF). NIST Special Publication 800-53A, Revision 4. https://nvlpubs.nist.gov/nistpubs/SpecialPublications/NIST.SP.800-53Ar4.pdf. Retrieved 01 February 2018.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 ISACA. "COBIT 5". https://cobitonline.isaca.org/. Retrieved 01 February 2018.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 International Standards Organization. "ISO/IEC 27001:2013 - Information technology — Security techniques — Information security management systems — Requirements". https://www.iso.org/standard/54534.html. Retrieved 01 February 2018.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 ISA (13 January 2009). "Security for industrial automation and control systems, Part 2-1: Establishing an industrial automation and control systems security program" (PDF). ANSI/ISA-62443-2-1 (99.02.01)-2009. http://www.icsdefender.ir/files/scadadefender-ir/paygahdanesh/standards/ISA-62443-2-1-Public.pdf. Retrieved 13 March 2018.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 ISA (12 August 2013). "Security for industrial automation and control systems, Part 3-3: System security requirements and security levels" (PDF). ANSI/ISA-62443-3-3 (99.03.03)-2013. http://www.icsdefender.ir/files/scadadefender-ir/paygahdanesh/standards/ISA-62443-3-3-Public.pdf. Retrieved 13 March 2018.

- ↑ Microsoft. "Microsoft Power BI". https://powerbi.microsoft.com/en-us/. Retrieved 12 April 2018.

- ↑ Angelini, M.; Lenti, S.; Santucci, G. (2017). "CRUMBS: A cyber security framework browser". Proceedings from the 2017 IEEE Symposium on Visualization for Cyber Security: 1–8. doi:10.1109/VIZSEC.2017.8062194.

- ↑ Abrams, M.; Weiss, J. (23 July 2008). "Malicious Control System Cyber Security Attack Case Study– Maroochy Water Services, Australia" (PDF). MITRE Corporation. https://www.mitre.org/sites/default/files/pdf/08_1145.pdf. Retrieved 29 January 2018.

- ↑ Casey, T.; Fiftal, K.; Landfield, K. et al. (January 2015). "The Cybersecurity Framework in Action: An Intel Use Case" (PDF). Intel Corporation. https://supplier.intel.com/static/governance/documents/The-cybersecurity-framework-in-action-an-intel-use-case-brief.pdf. Retrieved 30 January 2018.

- ↑ Biological Sciences Division (April 2016). "Applying the Cybersecurity Framework at the University of Chicago – An Education Case Study" (PDF). University of Chicago. http://security.bsd.uchicago.edu/wp-content/uploads/sites/2/2016/04/BSD-Framework-Implementation-Case-Study_final_edition.pdf. Retrieved 31 January 2018.

- ↑ Sweeney, S., Young, L.R. (October 2015). "How the University of Pittsburgh Is Using the NIST Cybersecurity Framework". Carnegie Mellon University. https://resources.sei.cmu.edu/library/asset-view.cfm?assetid=445056. Retrieved 01 february 2018.

- ↑ Montesino, R.; Fenz, S.; Baluja, W. (2012). "SIEM‐based framework for security controls automation". Information Management & Computer Security 20 (4): 248–63. doi:10.1108/09685221211267639.

- ↑ Kim, E.B. (2014). "Recommendations for information security awareness training for college students". Information Management & Computer Security 22 (1): 115-126. doi:10.1108/IMCS-01-2013-0005.

- ↑ BSI (July 2011). "Embedding world-class information security management as the platform for rapid business growth" (PDF). https://www.bsigroup.com/Documents/iso-27001/case-studies/BSI-ISO-IEC-27001-case-study-Thames-Security-UK-EN.pdf?epslanguage=en-MY. Retrieved 15 February 2018.

- ↑ BSI (October 2012). "How Fredrickson has reduced third party scrutiny and protected its reputation with ISO 27001 certification" (PDF). https://www.bsigroup.com/Documents/iso-27001/case-studies/BSI-ISO-IEC-27001-case-study-Fredrickson-International-EN-UK.pdf?epslanguage=en-MY. Retrieved 15 February 2018.

- ↑ BSI (April 2013). "Implementing best practice and improving client confidence with ISO/IEC 27001" (PDF). https://www.bsigroup.com/Documents/iso-27001/case-studies/BSI-ISO-IEC-27001-case-study-Legal-Ombudsman-UK-EN.pdf. Retrieved 15 February 2018.

- ↑ BSI (June 2013). "Supporting business growth with ISO/IEC 27001" (PDF). https://www.bsigroup.com/Documents/iso-27001/case-studies/BSI-ISO-IEC-27001-case-study-SVM-UK-EN.pdf. Retrieved 15 February 2018.

- ↑ BSI (2013). "InfoView Case Study" (PDF). Archived from Studies/BSI Infoview Case Study.pdf the original on 24 April 2016. https://web.archive.org/web/20160424133846/https://www.bsigroup.com/LocalFiles/EN-AU/_Case%20Studies/BSI%20Infoview%20Case%20Study.pdf. Retrieved 15 February 2018.

- ↑ BSI (May 2013). "Using ISO/IEC 27001 certification to increase resilience, reassure clients and gain a competitive edge" (PDF). https://www.bsigroup.com/Documents/iso-27001/case-studies/BSI-ISO-IEC-27001-case-study-Capgemini-UK-EN.pdf. Retrieved 15 February 2018.

- ↑ BSI (June 2013). "Integrating management systems to improve business performance and achieve sustained competitive advantage" (PDF). https://www.bsigroup.com/Documents/iso-22301/case-studies/Costain-case-study-UK-EN.pdf. Retrieved 15 February 2018.

- ↑ Committee of Sponsoring Organizations of the Treadway Commission. "Guidance on Enterprise Risk Management". https://www.coso.org/Pages/erm.aspx. Retrieved 06 March 2018.

- ↑ Center for Internet Security. "CIS Controls". https://www.cisecurity.org/controls/. Retrieved 06 March 2018.

- ↑ Information Security Forum. "The ISF Standard of Good Practice for Information Security 2018". https://www.securityforum.org/tool/the-isf-standard-good-practice-information-security-2018/. Retrieved 08 March 2018.

- ↑ Brookson, C. (September 2017). "Cybersecurity: Overview of Cybersecurity". ETSI. https://www.enisa.europa.eu/events/enisa-cscg-2017/presentations/brookson. Retrieved 07 March 2018.

- ↑ SABSA. "SENC: SABSA Enhanced NIST Cybersecurity Framework". https://sabsa.org/sabsa-nist-framework-project/. Retrieved 21 March 2018.

- ↑ IASME. "About Cyber Essentials". https://iasme.co.uk/cyberessentials/about-cyber-essentials/. Retrieved 07 March 2018.

- ↑ Fraser, B., ed. (September 1997). "RFC 2196 - Site Security Handbook". IETF. https://www.ietf.org/rfc/rfc2196.txt. Retrieved 08 March 2018.

- ↑ HITRUST (September 2017). "Introduction to the HITRUST CSF, Version 9.0" (PDF). https://hitrustalliance.net/documents/csf_rmf_related/v9/CSFv9Introduction.pdf. Retrieved 21 March 2018.

- ↑ Vinson & Elkins (2014). "Summary of CIP Version 5 Standards" (PDF). https://www.velaw.com/uploadedfiles/vesite/resources/summarycipversion5standards2014.pdf. Retrieved 12 February 2018.

- ↑ OSA. "OSA Landscape". http://www.opensecurityarchitecture.org/cms/foundations/osa-landscape. Retrieved 15 March 2018.

- ↑ CYSEC. "GPG13 Executive Summary". http://gpg13.com/executive-summary/. Retrieved 13 March 2018.

Notes

This presentation is faithful to the original, with only a few minor changes to presentation, grammar, and punctuation. In some cases important information was missing from the references, and that information was added. The original article lists references alphabetically, but this version—by design—lists them in order of appearance. Some original references had broken URLs; this version updates them to functional URLs. In one case, an archived version of the article had to be used.