Journal:Delta-8-THC: Delta-9-THC’s nicer younger sibling?

| Full article title | Delta-8-THC: Delta-9-THC’s nicer younger sibling? |

|---|---|

| Journal | Journal of Cannabis Research |

| Author(s) | Kruger, Jessica S.; Kruger, Daniel J. |

| Author affiliation(s) | State University of New York at Buffalo, University of Michigan |

| Primary contact | Email: jskruger at buffalo dot edu |

| Year published | 2022 |

| Volume and issue | 24 |

| Article # | 4 |

| DOI | 10.1186/s42238-021-00115-8 |

| ISSN | 2522-5782 |

| Distribution license | Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International |

| Website | https://jcannabisresearch.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s42238-021-00115-8 |

| Download | https://jcannabisresearch.biomedcentral.com/track/pdf/10.1186/s42238-021-00115-8.pdf (PDF) |

Abstract

Background: Products containing delta-8-tetrahydrocannabinol (Δ8-THC) became widely available in most of the United States following the 2018 Farm Bill, and by late 2020, those products were core products of hemp processing companies, especially where delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol (Δ9-THC) use remained illegal or required medical authorization. Research on experiences with Δ8-THC is scarce, and some state governments have prohibited it because of this lack of knowledge.

Objective: We conducted an exploratory study addressing a broad range of issues regarding Δ8-THC to inform policy discussions and provide directions for future systematic research.

Methods: We developed an online survey for Δ8-THC consumers, including qualities of Δ8-THC experiences, comparisons with Δ9-THC, and open-ended feedback. The survey included quantitative and qualitative aspects to provide a rich description and content for future hypothesis testing. Invitations to participate were distributed by a manufacturer of Δ8-THC products via social media accounts, email contact list, and the Delta8 Reddit.com discussion board. Participants (n = 521) mostly identified as White/European American (90%) and male (57%). Pairwise t tests compared Δ8-THC effect rating items; one-sample t tests examined responses to Δ9-THC comparison items.

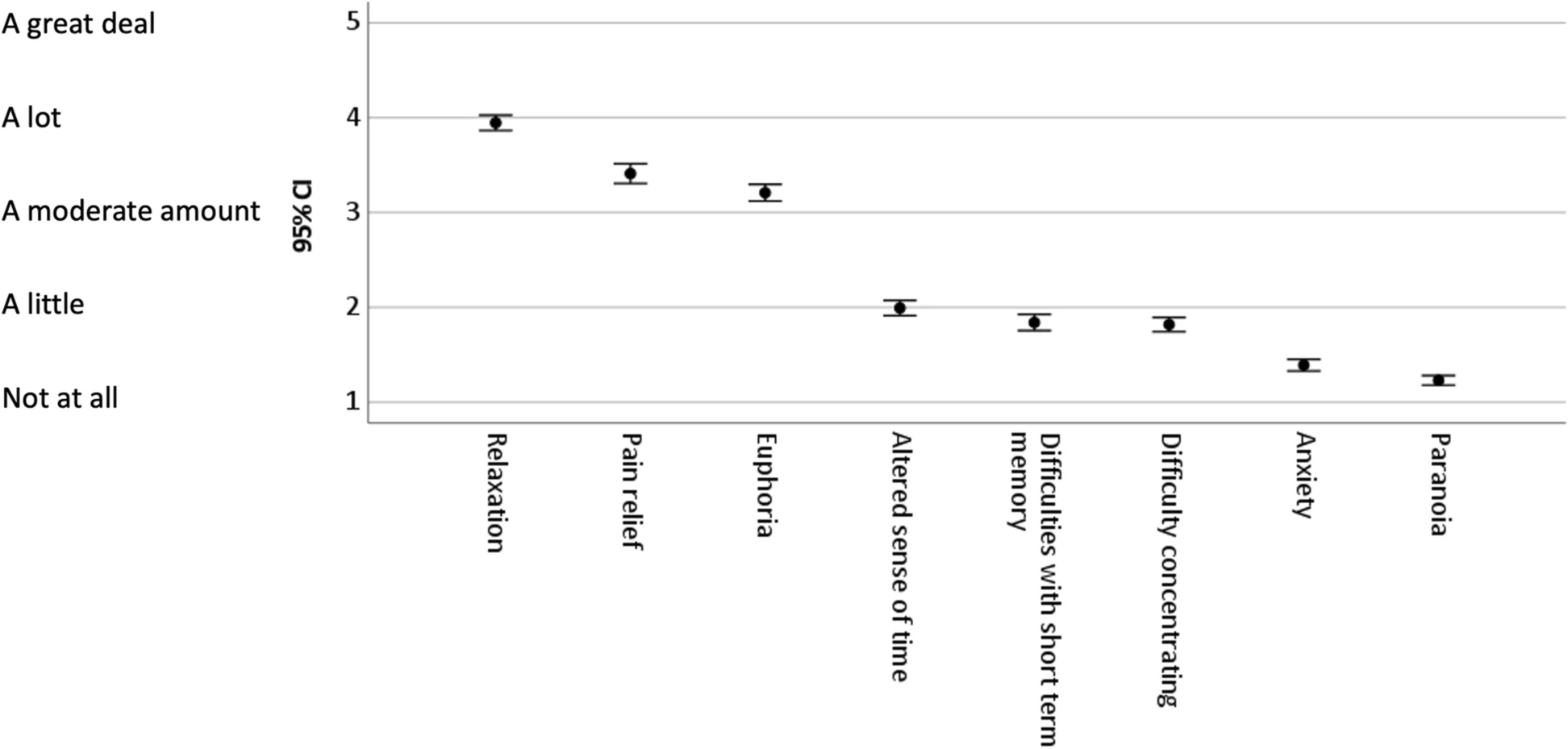

Results: Most Δ8-THC users experienced a lot or a great deal of relaxation (71%); euphoria (68%) and pain relief (55%); and a moderate amount or a lot of cognitive distortions such as difficulty concentrating (81%), difficulties with short-term memory (80%), and alerted sense of time (74%). Many did not experience anxiety (74%) or paranoia (83%). Participants generally compared Δ8-THC favorably with both Δ9-THC and pharmaceutical drugs, with most participants reporting substitution for Δ8-THC (57%) and pharmaceutical drugs (59%). Participant concerns regarding Δ8-THC were generally focused on continued legal access.

Conclusions: Δ8-THC may provide much of the experiential benefits of Δ9-THC with fewer adverse effects. Future systematic research is needed to confirm participant reports, although these studies are hindered by the legal statuses of both Δ8-THC and Δ9-THC. Cross-sector collaborations among academics, government officials, and representatives from the cannabis industry may accelerate the generation of knowledge regarding Δ8-THC and other cannabinoids. A strength of this study is that it is the first large survey of Δ8-THC users; limitations include self-reported data from a self-selected convenience sample.

Keywords: medical cannabis, cannabis, cannabinoid, delta-8-THC, subjective effects

Background

Among hundreds of cannabinoids, delta-8-tetrahydrocannabinol (Δ8-THC or delta-8-THC) has rapidly risen in popularity among consumers of cannabis products. Δ8-THC is an isomer or a chemical analog of delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol (Δ9-THC or delta-9-THC), the molecule that produces the experience of being high when ingesting cannabis.[1] Δ8-THC differs in the molecular structure from Δ9-THC in the location of a double bond between carbon atoms 8 and 9 rather than carbon atoms 9 and 10.[2] Due to its altered structure, Δ8-THC has a lower affinity for the CB1 receptor and therefore has a lower psychotropic potency than Δ9-THC.[2][3] Δ8-THC is found naturally in the Cannabis plant, though at substantially lower concentrations than Δ9-THC.[4] It can also be synthesized from other cannabinoids.[5]

The 2018 Farm Bill did not specifically address Δ8-THC, but it effectively legalized the sale of hemp-derived Δ8-THC products with no oversight. Its popularity grew dramatically in late 2020, gaining the attention of cannabis consumers and processors throughout the United States. As of early 2021, Δ8-THC is considered one of the fastest-growing segments of hemp derived products, with most states having access.[6] However, little is known about experiences with Δ8-THC or its effects in medical or recreational users.[2][3]

In 1973, Δ8-THC and Δ9-THC were administrated to six research participants. Despite the small sample size, researchers concluded that Δ8-THC was about two-thirds as potent as Δ9-THC and was qualitatively similar in experiential effects.[2][3] In 1995, researchers gave Δ8-THC to eight pediatric cancer patients two hours before each chemotherapy session. Over the course of eight months, none of these patients vomited following their cancer treatment. The researchers concluded that Δ8-THC was a more stable compound than the more well-studied Δ9-THC[7], consistent with other findings[8], suggesting that Δ8-THC could be a better candidate than Δ9-THC for new therapeutics.

In recent months, 14 U.S. states have blocked the sale of Δ8-THC due to the lack of research into the compound’s psychoactive effects.[9] However, all policies and practices, including those related to substance use and public health, should be informed by empirical evidence. The current study seeks to better understand the experiences of people who use Δ8-TH to inform policy discussions and provide directions for future systematic research. Because this is the first large survey of Δ8-THC consumers, we take an exploratory approach to describe experiences with Δ8-THC. We combine quantitative rating items with open-ended qualitative items, enabling participants to provide feedback which is rich in content.

Methods

Procedures

We developed an anonymous Qualtrics online survey to assess experiences with Δ8-THC. Bison Botanics, a manufacturer of Δ8-THC and cannabidiol (CBD) products in New York State, distributed invitations to participate in the study via their social media accounts (Facebook, Instagram), via their email contact list, and via the Delta8 online discussion board (Subreddit) on Reddit.com. The invitation read: “Are you a Delta-8-THC consumer? We’ve partnered with researchers at the University at Buffalo and the University of Michigan to learn more about experiences with delta-8-THC and its impact on public health and safety.” Screening questions verified that participants were 18 years of age or older, were currently in the USA, and used or consumed products containing Δ8-THC. Surveys were completed between June 12 and August 2, 2021. Δ8-THC products were sold legally in New York State until July 19, 2021.

Participants

Completed surveys (n = 521) were included for analyses, with a completion rate of 74%. Participants were men (57%), women (41%), and individuals who reported another gender identity (2%). The mean age was 34 years old (SD = 11; range: 18–76). Participants had completed 15 years of education on average (SD = 2; range: 8–20) and 17% were currently students. Participants identified (inclusively) as White/European American (90%), Hispanic/Latino (5%), Black/African American (3%), American Indian or Alaska Native (3%), Asian (3%), Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander (1%), and Other (3%). Most (59%) participants provided zip codes, which ranged across 38 U.S. states. The largest portion was from New York State (29%), with all other states representing below 10% of the total. Nearly all these participants (90%) were in states where Δ9-THC cannabis products were not yet commercially available for adult (i.e., “recreational”) use.

Measures

Participants reported on the content of their experiences with Δ8-THC by rating its effects. The question stem read: “Please indicate how much you experience the following when you use delta-8-THC.” Specific experiential aspects included altered sense of time; anxiety (unpleasant feelings, nervousness, worry); difficulty concentrating; difficulties with short-term memory; euphoria (pleasure, excitement, happiness); pain relief; paranoia (thinking that other people are out to get you, etc.); and relaxation. Response options were "not at all," "a little," "a moderate amount," "a lot," and "a great deal."

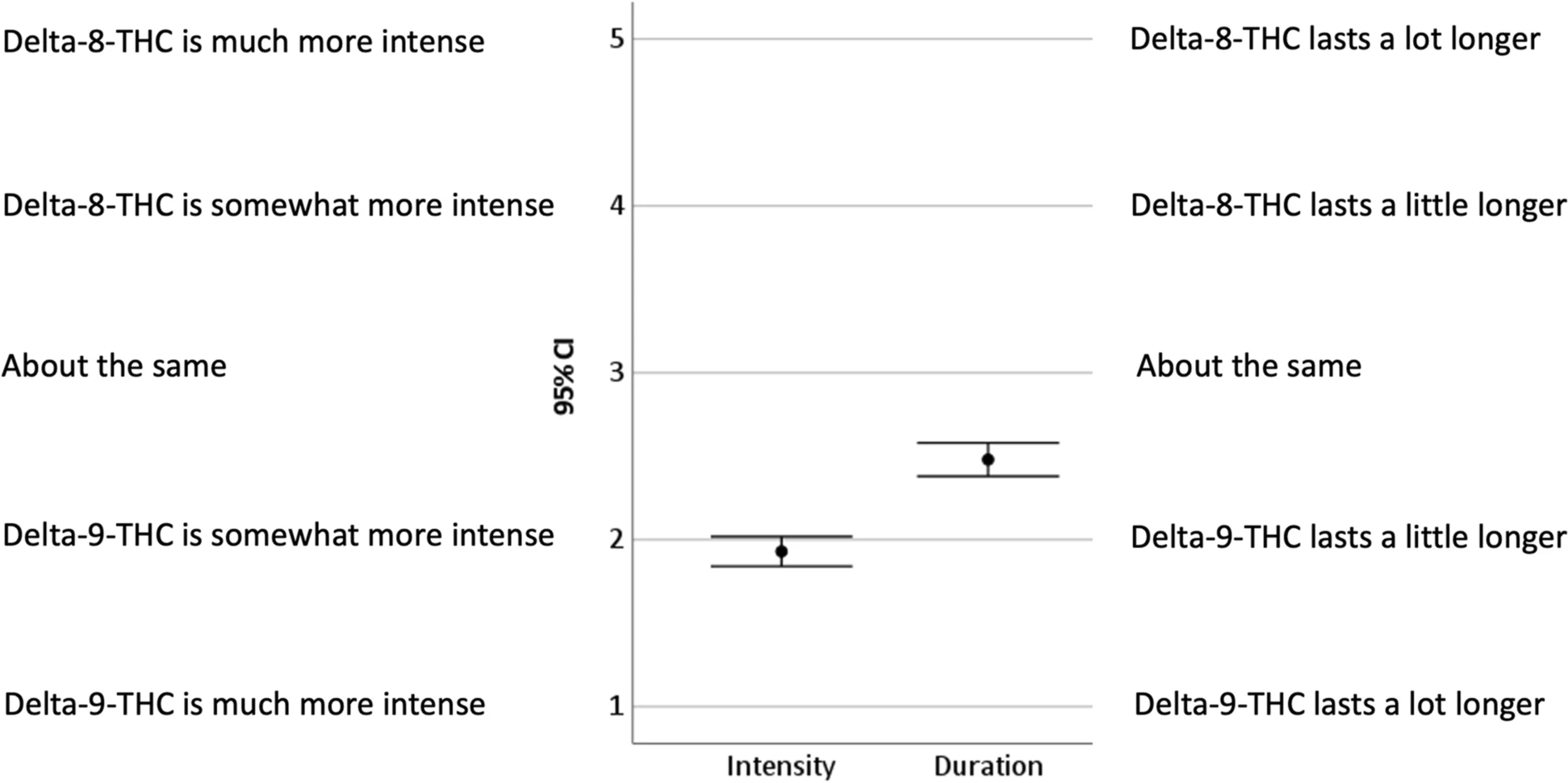

Two items assessed participants’ comparisons of experiences with Δ8-THC and Δ9-THC. The first question read: “How does Delta-8-THC compare to Delta-9-THC in the intensity or strength of effects?” [emphasis in original]. Response options were: "Delta-8-THC is much more intense," "Delta-8-THC is somewhat more intense," "about the same," "Delta-9-THC is somewhat more intense," "Delta-9-THC is much more intense," and "do not know." The second question read: “How does Delta-8-THC compare to Delta-9-THC in the duration or length of effects?” [emphasis in original]. Response options were: "Delta-8-THC lasts a lot longer," "Delta-8-THC lasts a little longer," "about the same," "Delta-9-THC lasts a little longer," "Delta-9-THC lasts a lot longer," and "do not know."

Participants were also asked the open-ended question, “Do you have any comments about how Delta-8-THC compares to Delta-9-THC?” after the rating items. This item was followed by a brief demographic section assessing age, gender identity, education, ethnicity, and zip code. At the end of the survey, participants were asked, “Do you have any comments about these topics or this survey?” There were no restrictions on participants’ responses.

Analysis

Pairwise t tests compared ratings on Δ8-THC effect items; descriptive statistics, 95% confidence intervals, and effect sizes were calculated (see Table 1 and Fig. 1). Responses to items comparing Δ8-THC to Δ9-THC intensity and duration were examined by one-sample t tests with a comparison value of 3 (“About the same”), effect sizes and 95% confidence intervals were calculated (see Fig. 2). Demographic comparisons were made for participants’ gender with between-subjects t tests, participants’ age with Pearson correlations, and participants’ educational levels with partial correlations controlling for age. Responses to open-ended questions were coded as a set to avoid the duplication of codes for the same participant (see Table 2). The coders had been trained in qualitative methods, and an inductive coding method was used to create a codebook. After the first coder assigned the codes, a line-by-line coding was used to then categorize codes. To establish inter-rater reliability, two coders independently read participant responses and identified overall themes. Once general themes were established, the responses were coded for theme categories and subcategories. Coding discrepancies were resolved and coding omissions were eliminated by adding codes, although no previously identified themes were deleted. Instances of themes and subthemes were calculated across participants. Individual participants could express more than one subtheme within a thematic category.

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Results

Participants mostly consumed Δ8-THC through edibles (64%; brownies, gummies, etc.), vaped concentrates (48%; hash, wax, dabs, oil, etc.), and tinctures (32%). Some participants consumed Δ8-THC through smoking concentrates (23%; hash, wax, dabs, oil, etc.), smoking bud or flower (18%), vaping bud or flower (9%), topical products (9%; lotion, cream, oil, patch on skin), capsules (6%), suppositories (1%), and other methods (1%). Most participants (83%) also reported consuming Δ9-THC cannabis and products and reported substitution for Δ9-THC (57%) and pharmaceutical drugs (59%).

Experiences with Δ8-THC were most prominently characterized by relaxation, pain relief, and euphoria (see Table 1 and Fig. 1). Participants reported modest levels of cognitive distortions such as an altered sense of time, difficulties with short-term memory, and difficulty concentrating. Participants reported low levels of distressing mental states (anxiety and paranoia). There were large statistical effect sizes in differences between items in the first set of experiences (relaxation, pain relief, and euphoria) and items in the second set (cognitive distortions), and medium statistical effect sizes in differences between cognitive distortions and anxiety and paranoia.

On average participants reported that the effects of Δ8-THC were less intense—t(433) = 23.86, p < .001, d = 1.15—and had a shorter duration—t(421) = 10.08, p < .001, d = 0.49—than the effects of Δ9-THC (see Fig. 2). Proportionally, participants reported the intensity of effect as much more with Δ9-THC (36%), somewhat more with Δ9-THC (44%), about the same (15%), somewhat more with Δ8-THC (4%), and much more with Δ8-THC (2%). Proportionally, participants reported the duration of effect as much more with Δ9-THC (20%), somewhat more with Δ9-THC (27%), about the same (41%), somewhat more with Δ8-THC (8%), and much more with Δ8-THC (5%).

Demographic analyses indicated that women perceived Δ8-THC effects to be somewhat more intense—t(420) = 3.55, p < .001, d = 0.36—and longer lasting—t(408) = 3.45, p < .001, d = 0.36—compared to Δ9-THC than did men. Older individuals perceived Δ8-THC effects to be somewhat more intense—r(429) = .141, p = .003—and longer lasting— r(418) = .293 p < .001—compared to Δ9-THC than younger individuals. Controlling for age, those completing more years of education perceived Δ8-THC effects to be somewhat more intense—r(383) = .158, p = .003—and longer lasting—r(383) = .139, p = .006—compared to Δ8-THC than those with less education.

Participants (n = 204) provided text responses in one or both open-ended questions (see Table 2 and S1). The most common theme was comparisons between Δ8-THC and Δ9-THC. Examples of participants’ responses containing this theme included:

- “Delta 8 feels like Delta 9’s nicer younger sibling.”

- “It has all the positives and many fewer drawbacks/side effects. It is less impairing and much less likely to cause anxiety or paranoia. It has much milder to nonexistent aftereffects.”

- “Delta 8 is not as heavy as Delta 9. With Delta 8, I am able to perform my normal day to day activities, i.e., no couch lock, paranoia, munchies. I am able to function well at work under the influence of Delta 8 whereas under the influence on Delta 9 at work, I am paranoid and feel less motivated to do work activities. Delta 8 has more of just a euphoria feeling than any other feeling for me. I want to do activities and I want to have a pleasurable time. Whereas if I have too much of Delta 9, all I want to do is watch TV, eat snacks, distance myself from the outside world. Delta 9 is better for sleep.”

The second most common theme was the therapeutic effect or benefit from Δ8-THC. Examples of participants’ responses containing this theme included:

- “It is like 'lite' Delta 9. I can focus and work more with Delta 8 than Delta 9. It helps my pains and relaxation and I feel more able. Depending on the strain it has taken the place of melatonin for sleep.”

- “As with any newer drug with limited study, care should be taken with its use. But I’ve personally found it immensely useful and therapeutic, with management of anxiety and sleep issues. Which nothing but far more addictive drugs (regarding anxiolytics), have helped with in the past. I hope lots more studies will be able to be done.”

- “Delta-9 I pretty regularly experience panic attacks. Delta-8 I do not and it relieves symptoms of PTSD and anxiety pretty quickly.”

The third most common theme was comments on the study or researchers. Some examples of this praise include:

- “I'm glad that there's more academic research being done on the subject, thank you for doing it!”

- “Keep up the good work. Need more studies and information on cannabinoids.”

The fourth most common theme was expressions of concern, particularly for continued legal access to Δ8-THC. Examples of participants’ responses containing this theme included:

- “D8 is Great for daytime relief when you need to get stuff done. It has helped me a lot! I HOPE THEY DON’T BAN IT!”

- “I feel that delta-8-THC is a very effective alternative to delta-9-THC with less side effects. I primarily consume it in combination with high CBD or CBG hemp. I do wish there was regulation purely for safety concerns; more reliable lab testing, testing specifically for solvents and reagents used in delta-8-THC production, etc. But I do fear that harsh regulation may get in the way of a wonderful substance that could improve the lives of many people. I hope against hope that a fear mongering campaign doesn't put an end to the golden age of D8 that we are currently experiencing.”

The fifth most common theme was general expressions of praise for Δ8-THC. Many participants had similar statements such as, “Delta 8 is a great thing. It needs to stay accessible and affordable for the people that can really benefit.”

The sixth most common theme was substitution of Δ8-THC for other substances. One participant stated: “The therapeutic and medicinal effects of Delta 8 have significantly improved my life, treating pain and sleeplessness while not making me feel the high I get from Delta 9. I have stopped taking pharmaceutical drugs and my health and wellbeing has improved.”

The seventh most common theme was the dual use of Δ8-THC and Δ9-THC. One representative comment was: “It seems a lot more of a ‘functional’ high, at my job we call it work-weed. I get too much anxiety to effectively deal with customers on Delta 9, Delta 8 is just about perfect for when you gotta actually do things. I still do prefer Delta-9 after a long day though.”

The eighth most common theme was adverse effects of Δ8-THC. One example: “I love Delta 8 because I do not need to take it daily. I’ve never had withdrawals when I did not take it. What I dislike about Delta 8 is the feeling of always being cold. I did read the dosage had something to do with this but unfortunately even reducing the dosage gave me the same result.”

Participants also made comments that did not fit into the major themes. The most frequent of these comments was that Δ8-THC edibles or tinctures were more powerful than when Δ8-THC was inhaled as a vape. A representative comment was, “How Delta 8 is consumed plays a large role in the effects, when eaten or taken in a tincture it feels much closer to Delta 9 in effects compared to when vaping/dabbing Delta 8.”

Discussion

Participants’ reports were overall supportive of the use of Δ8-THC. Comparisons reveal that Δ8-THC experiences are primarily characterized by beneficial effects and are low in potentially adverse effects associated with cannabis use. Experiences of relaxation, pain relief, and euphoria were the most prominent, characterized as between “a moderate amount” and “a lot” on average. Participants reported “a little” of the cognitive distortions associated with Δ9-THC and cannabis use in general. Experiences such as an alerted sense of time, difficulties with short-term memory, and difficulty concentrating may not be problematic for consumers in certain contexts (e.g., relaxation and socialization); however they may in in others (e.g., operating a motor vehicle). Paranoia and anxiety are distressing mental states that may result from Δ9-THC ingestion.[10] On average, participants’ experiences of paranoia and anxiety were between “not at all” and “a little.” Experiences with Δ8-THC were characterized as less intense and with somewhat shorter duration than those with Δ8-THC.

Participant reports included a wealth of other information that can inform hypothesis testing and research questions in future studies. For example, it would be valuable to conduct systematic studies comparing experiences of Δ8-THC with Δ9-THC and pharmaceutical drugs. Participants viewed Δ8-THC experiences favorably in comparison, and most participants reported substitution of Δ8-THC for both Δ9-THC and pharmaceutical drugs, consistent with comparisons and substitutions of pharmaceuticals with cannabis products in general.[11][12][13] Participants reported being more active and productive with Δ8-THC than with Δ9-THC, and some suggested that Δ8-THC was more purely therapeutic than Δ9-THC. Participants also reported notable adverse experiences with Δ8-THC, most commonly that Δ8-THC is harsher on the lungs than Δ9-THC when inhaled.

Some of the variation in experiences across individuals is likely due to inconsistencies in the products consumed, particularly in dosage, administration method, and impurities. Manufacturers have adjusted for the lower potency of Δ8-THC by increasing the dosage (e.g., 25 mg in edibles) relative to similar Δ9-THC products (where one dose has been defined as 10 mg).[14][15] The US Cannabis Council tested 16 samples of non-cannabis-based products featuring Δ8-THC in April 2021 and found Δ9-THC levels ranging from 1.3 to 5.3% (well above the 0.3% level allowed in the 2018 Farm Bill), as well as heavy metals and unknown compounds in some of the samples.[16] It is possible that substances other than Δ8-THC contributed to both beneficial and adverse experiences in user reports.

Policy considerations

The 2018 Farm Bill (U.S. Agriculture Improvement Act of 2018) created a legal loophole for the sale of hemp-derived Δ8-THC products in areas without legal adult use (i.e., recreational) and where the medical use of cannabis and cannabis products containing Δ9-THC requires medical authorization. Manufacturing and sales of Δ8-THC products skyrocketed due to greater accessibility to fulfill market demand. Yet, some states have made Δ8-THC sales illegal. Paradoxically, of these 14 states, six allow recreational Δ9-THC cannabis, 10 allow for medical Δ9-THC cannabis, and three have decriminalized recreational use of Δ9-THC cannabis.

The current study provides empirical evidence to inform discussions of Δ8-THC-related policies and practices. More research is needed to isolate the psychoactive effects of Δ8-THC and its possible therapeutic benefits and make valid comparisons with pharmaceutical drugs and other cannabinoids, as well as their risks and adverse effects. Such studies currently face considerable legal barriers, such as the Schedule I status of Δ9-THC. Banning Δ8-THC products while allowing the sale of Δ9-THC products seems inconsistent both in cannabis policy and in relation to our study results. Current results suggest that Δ8-THC products have therapeutic benefits, and typical administration routes (consumption as an edible, tincture, or by vaping) may produce less harm than smoking cannabis flower. Vaping is considered a harm reduction solution.[17]

Harm reduction is a set of practical strategies and ideas aimed at reducing negative consequences associated with drug use.[18] It is also a movement for social justice built on a belief in, and respect for, the rights of people who use drugs. Harm reduction has been widely used with various other substances, such as opioids[19], alcohol[18], and tobacco.[20] Interventions based on harm reduction principles have been successful in reducing risk behaviors related to cannabis use, such as driving while under the influence of cannabis.[21] Although our results are largely descriptive, we provide an initial encouraging assessment of the suitability of the use of Δ8-THC as a possible harm reduction practice.

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has recommended collaborative research partnerships among academic researchers, government officials, and representatives from the cannabis industry to inform public health decisions related to CBD, another cannabinoid with rapidly growing use.[22] Similar research collaborations may accelerate the generation of knowledge regarding Δ8-THC and other cannabinoids.

Limitations

This study compiled the self-reported experiences of Δ8-THC consumers. The patterns of experiences reported here require verification with carefully controlled studies, such as double-blind and randomized studies for comparisons of Δ8-THC with Δ9-THC and pharmaceutical drugs. The current study assessed participants’ naturalistic experiences, rather than experiences with a specific Δ8-THC product. Participants were recruited through the social networks of a Δ8-THC and CBD product manufacturer and a Δ8-THC social media interest group. Participant reports may be more enthusiastic than those of a randomly selected population-representative sample.

Conclusions

Δ8-THC products may provide much of the experiential and therapeutic benefits of Δ9-THC with lower risks and fewer adverse effects. Substitution of Δ8-THC for Δ9-THC may be consistent with harm reduction, one of the core principles of public health. The current study provided a broad descriptive assessment of self-reported experiences with Δ8-THC. Further systematic research will be critical in verifying the favorable reports of Δ8-THC consumers.

Supplementary information

- Table S1: Unique themes in responses to open-ended questions

Abbreviations

CBD: Cannabidiol

NASEM: National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine

PTSD: Post-traumatic stress disorder

SD : Standard deviation

THC: Tetrahydrocannabinol

Acknowledgements

We thank Bison Botanics and survey participants for their assistance with this project.

Author contributions

All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

Not applicable.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board for Health Sciences and Behavioral Sciences at the University of Michigan prior to data collection. Participants indicated their consent by completing the survey after viewing the informed consent form.

Availability of data and materials

The dataset used and analyzed for the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

References

- ↑ Qamar, Sadia; Manrique, Yady J.; Parekh, Harendra S.; Falconer, James R. (28 May 2021). "Development and Optimization of Supercritical Fluid Extraction Setup Leading to Quantification of 11 Cannabinoids Derived from Medicinal Cannabis" (in en). Biology 10 (6): 481. doi:10.3390/biology10060481. ISSN 2079-7737. PMC PMC8227983. PMID 34071473. https://www.mdpi.com/2079-7737/10/6/481.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 Razdan, Raj K. (1984), Agurell, S.; Dewey, W.L.; Willette, R.E., ed., "CHEMISTRY AND STRUCTURE-ACTIVITY RELATIONSHIPS OF CANNABINOIDS: AN OVERVIEW" (in en), The Cannabinoids: Chemical, Pharmacologic, and Therapeutic Aspects (Elsevier): 63–78, doi:10.1016/b978-0-12-044620-9.50009-9, ISBN 978-0-12-044620-9, https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/B9780120446209500099

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 Hollister, Leo E.; Gillespie, H. K. (1 May 1973). "Delta-8- and delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol; Comparison in man by oral and intravenous administration" (in en). Clinical Pharmacology & Therapeutics 14 (3): 353–357. doi:10.1002/cpt1973143353. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/cpt1973143353.

- ↑ Hively, Richard L.; Mosher, William A.; Hoffmann, Friedrich W. (1 April 1966). "Isolation of trans-Δ 6 -Tetrahydrocannabinol from Marijuana" (in en). Journal of the American Chemical Society 88 (8): 1832–1833. doi:10.1021/ja00960a056. ISSN 0002-7863. https://pubs.acs.org/doi/abs/10.1021/ja00960a056.

- ↑ Hanus, L.; Krejci, Z. (1975). "Isolation of two new Cannabinoid acids from Cannabis Sativa L. of Czechoslovak origin". Acta Universitatis Palackianae Olomucensis Facultatis Medicae 74: 161–66. https://unov.tind.io/record/16345?ln=en.

- ↑ Richtel, M. (27 February 2021). "This Drug Gets You High, and Is Legal (Maybe) Across the Country". The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2021/02/27/health/marijuana-hemp-delta-8-thc.html. Retrieved 01 July 2021.

- ↑ Abrahamov, Aya; Abrahamov, Avraham; Mechoulam, R. (1 May 1995). "An efficient new cannabinoid antiemetic in pediatric oncology" (in en). Life Sciences 56 (23-24): 2097–2102. doi:10.1016/0024-3205(95)00194-B. https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/002432059500194B.

- ↑ Zias, J.; Stark, H.; Sellgman, J.; Levy, R.; Werker, E.; Breuer, A.; Mechoulam, R. (20 May 1993). "Early medical use of cannabis". Nature 363 (6426): 215. doi:10.1038/363215a0. ISSN 0028-0836. PMID 8387642. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/8387642.

- ↑ Sullivan, K. (28 June 2021). "Delta-8 THC is legal in many states, but some want to ban it". NBC News. https://www.nbcnews.com/health/health-news/delta-8-thc-legal-many-states-some-want-ban-it-n1272270. Retrieved 01 July 2021.

- ↑ Freeman, Daniel; Dunn, Graham; Murray, Robin M.; Evans, Nicole; Lister, Rachel; Antley, Angus; Slater, Mel; Godlewska, Beata et al. (1 March 2015). "How Cannabis Causes Paranoia: Using the Intravenous Administration of ∆ 9 -Tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) to Identify Key Cognitive Mechanisms Leading to Paranoia" (in en). Schizophrenia Bulletin 41 (2): 391–399. doi:10.1093/schbul/sbu098. ISSN 1745-1701. PMC PMC4332941. PMID 25031222. https://academic.oup.com/schizophreniabulletin/article-lookup/doi/10.1093/schbul/sbu098.

- ↑ Kruger, Daniel J.; Kruger, Jessica S. (1 January 2019). "Medical Cannabis Users’ Comparisons between Medical Cannabis and Mainstream Medicine" (in en). Journal of Psychoactive Drugs 51 (1): 31–36. doi:10.1080/02791072.2018.1563314. ISSN 0279-1072. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/02791072.2018.1563314.

- ↑ Lucas, Philippe; Walsh, Zach; Crosby, Kim; Callaway, Robert; Belle-Isle, Lynne; Kay, Robert; Capler, Rielle; Holtzman, Susan (1 May 2016). "Substituting cannabis for prescription drugs, alcohol and other substances among medical cannabis patients: The impact of contextual factors: Cannabis substitution" (in en). Drug and Alcohol Review 35 (3): 326–333. doi:10.1111/dar.12323. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/dar.12323.

- ↑ Reiman, Amanda; Welty, Mark; Solomon, Perry (1 January 2017). "Cannabis as a Substitute for Opioid-Based Pain Medication: Patient Self-Report" (in en). Cannabis and Cannabinoid Research 2 (1): 160–166. doi:10.1089/can.2017.0012. ISSN 2378-8763. PMC PMC5569620. PMID 28861516. http://www.liebertpub.com/doi/10.1089/can.2017.0012.

- ↑ Sideris, Alexandra; Khan, Fahad; Boltunova, Alina; Cuff, Germaine; Gharibo, Christopher; Doan, Lisa V. (1 May 2018). "New York Physicians' Perspectives and Knowledge of the State Medical Marijuana Program" (in en). Cannabis and Cannabinoid Research 3 (1): 74–84. doi:10.1089/can.2017.0046. ISSN 2378-8763. PMC PMC5899285. PMID 29662957. http://www.liebertpub.com/doi/10.1089/can.2017.0046.

- ↑ State of California Senate (27 June 2017). "SB-94 Cannabis: medicinal and adult use". California Legislative Information. https://leginfo.legislature.ca.gov/faces/billTextClient.xhtml?bill_id=201720180SB94. Retrieved 01 July 2021.

- ↑ U.S. Cannabis Council (2021). "The Unregulated Distribution And Sale Of Consumer Products Marketed As Delta-8 THC" (PDF). U.S. Cannabis Council. https://irp.cdn-website.com/6531d7ca/files/uploaded/USCC%20Delta-8%20Kit.pdf. Retrieved 01 July 2021.

- ↑ Fischer, Benedikt; Russell, Cayley; Sabioni, Pamela; van den Brink, Wim; Le Foll, Bernard; Hall, Wayne; Rehm, Jürgen; Room, Robin (1 August 2017). "Lower-Risk Cannabis Use Guidelines: A Comprehensive Update of Evidence and Recommendations" (in en). American Journal of Public Health 107 (8): e1–e12. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2017.303818. ISSN 0090-0036. PMC PMC5508136. PMID 28644037. http://ajph.aphapublications.org/doi/10.2105/AJPH.2017.303818.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 Marlatt, G. Alan; Larimer, Mary E.; Witkiewitz, Katie, eds. (2012). Harm reduction: pragmatic strategies for managing high-risk behaviors (2nd ed ed.). New York: Guilford Press. ISBN 978-1-4625-0256-1. OCLC 730404388. https://www.worldcat.org/title/mediawiki/oclc/730404388.

- ↑ Rouhani, Saba; Park, Ju Nyeong; Morales, Kenneth B.; Green, Traci C.; Sherman, Susan G. (1 December 2019). "Harm reduction measures employed by people using opioids with suspected fentanyl exposure in Boston, Baltimore, and Providence" (in en). Harm Reduction Journal 16 (1): 39. doi:10.1186/s12954-019-0311-9. ISSN 1477-7517. PMC PMC6591810. PMID 31234942. https://harmreductionjournal.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12954-019-0311-9.

- ↑ Parascandola, Mark (1 April 2011). "Tobacco Harm Reduction and the Evolution of Nicotine Dependence" (in en). American Journal of Public Health 101 (4): 632–641. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2009.189274. ISSN 0090-0036. PMC PMC3052352. PMID 21330596. http://ajph.aphapublications.org/doi/10.2105/AJPH.2009.189274.

- ↑ Poulin, Christiane; Nicholson, Jocelyn (1 December 2005). "Should harm minimization as an approach to adolescent substance use be embraced by junior and senior high schools?" (in en). International Journal of Drug Policy 16 (6): 403–414. doi:10.1016/j.drugpo.2005.11.001. https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S095539590500143X.

- ↑ Hahn, S.M. (8 January 2021). "Better Data for a Better Understanding of the Use and Safety Profile of Cannabidiol (CBD) Products". FDA Voices. U.S. Food and Drug Administration. https://www.fda.gov/news-events/fda-voices/better-data-better-understanding-use-and-safety-profile-cannabidiol-cbd-products. Retrieved 01 July 2021.

Notes

This presentation is faithful to the original, with only a few minor changes to presentation. Some grammar and punctuation was cleaned up to improve readability. In some cases important information was missing from the references, and that information was added.