Journal:Data to diagnosis in global health: A 3P approach

| Full article title | Data to diagnosis in global health: A 3P approach |

|---|---|

| Journal | BMC Medical Informatics and Decision Making |

| Author(s) | Pathinarupothi, Rahul Krishnan; Durga, P.; Rangan, Ekanath Srihari |

| Author affiliation(s) | Amrita School of Engineering, Amrita Institute of Medical Science |

| Primary contact | Email: rahulkrishnan @ am dot amrita dot edu |

| Year published | 2018 |

| Volume and issue | 18 |

| Page(s) | 78 |

| DOI | 10.1186/s12911-018-0658-y |

| ISSN | 1472-6947 |

| Distribution license | Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International |

| Website | https://bmcmedinformdecismak.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12911-018-0658-y |

| Download | https://bmcmedinformdecismak.biomedcentral.com/track/pdf/10.1186/s12911-018-0658-y (PDF) |

|

|

This article contains rendered mathematical formulae. You may require the TeX All the Things plugin for Chrome or the Native MathML add-on and fonts for Firefox if they don't render properly for you. |

Abstract

Background: With connected medical devices fast becoming ubiquitous in healthcare monitoring, there is a deluge of data coming from multiple body-attached sensors. Transforming this flood of data into effective and efficient diagnosis is a major challenge.

Methods: To address this challenge, we present a "3P" approach: personalized patient monitoring, precision diagnostics, and preventive criticality alerts. In a collaborative work with doctors, we present the design, development, and testing of a healthcare data analytics and communication framework that we call RASPRO (Rapid Active Summarization for effective PROgnosis). The heart of RASPRO is "physician assist filters" (PAF) that 1. transform unwieldy multi-sensor time series data into summarized patient/disease-specific trends in steps of progressive precision as demanded by the doctor for a patient’s personalized condition, and 2. help in identifying and subsequently predictively alerting the onset of critical conditions. The output of PAFs is a clinically useful, yet extremely succinct summary of a patient’s medical condition, represented as a motif, which could be sent to remote doctors even over SMS, reducing the need for data bandwidths. We evaluate the clinical validity of these techniques using support-vector machine (SVM) learning models measuring both the predictive power and its ability to classify disease condition. We used more than 16,000 minutes of patient data (N=70) from the openly available MIMIC II database for conducting these experiments. Furthermore, we also report the clinical utility of the system through doctor feedback from a large super-speciality hospital in India.

Results: The results show that the RASPRO motifs perform as well as (and in many cases better than) raw time series data. In addition, we also see improvement in diagnostic performance using optimized sensor severity threshold ranges set using the personalization PAF severity quantizer.

Conclusion: The RASPRO-PAF system and the associated techniques are found to be useful in many healthcare applications, especially in remote patient monitoring. The personalization, precision, and prevention PAFs presented in the paper successfully shows remarkable performance in satisfying the goals of the 3Ps, thereby providing the advantages of "3As": availability, affordability, and accessibility in the global health scenario.

Keywords: precision medicine, medical informatics, personalized healthcare, motif summarization

Background

Precision medicine and personalized healthcare are quickly gaining wide research interest as well as initial acceptance among the medical community. This is facilitated by the availability of ubiquitous data sources such as wearable sensors, smartphones, and internet of things (IoT) devices, along with machine learning and large-scale data analytics tools, resulting in promising outcomes in some of the niche medical domains. Our research particularly focuses on introducing the three Ps: precision, personalization, and preventive diagnosis in remote healthcare monitoring of patients, especially in a global health scenario. In our system, patients in remote areas use wearable devices to capture their vital parameters such as blood pressure (BP), blood glucose, oxygen saturation (SpO2), electro cardiographs (ECG) etc., and transmit them to doctors in tertiary care hospitals, who in turn are expected to suggest suitably needed timely interventions. While deploying our system in the highly populous region of southern India, we found that although this promises to provide hitherto unavailable healthcare services to a critically ill and aging population, particularly in the developing world, there are significant roadblocks in our expectation that doctors embrace this new paradigm in handling patients. The doctors, who are already overloaded, feel even more overwhelmed by the voluminous data flooding in from remote patients’ sensors. Furthermore, interpreting such incoming multi-parameter data simultaneously from a multitude of remote patients is time-consuming and soon transforms into an unmanageable deluge.

Approach

In this paper, we propose novel approaches to transform data into diagnosis. As a collaborative work between our researchers and clinicians in one of the largest super-specialty hospitals in India (Amrita Institute of Medical Sciences - AIMS), we developed physician assist filters (PAFs) that are designed to transform unwieldy time series sensor data into summarized patient/disease-specific trends in steps of progressive precision as demanded by the doctor for patient’s personalized condition at hand, and help in identifying and subsequently predictively alerting the onset of critical conditions. Together with the communication network and data transmission architecture, this new framework that we have designed, developed, and successfully deployed is called RASPRO (Rapid Active Summarization for effective PROgnosis) and was first introduced in 2016 IEEE Wireless Health.[1]

Related work

We begin by analyzing the existing systems that simply generate alerts every time one or more sensors cross the abnormality thresholds. Due to the sheer volume of such alerts, they are difficult to manage, even in the case of hospital in-patient settings, let alone for a much larger number of remotely monitored patients. Starting from some of the initial attempts reported by Anliker et al.[2], to more recent works from various researchers[3][4][5][6], the severity detection and alert generation is typically based either on predefined thresholds, or based on training of thresholds using machine learning followed by online classification of multi-sensor data. Very similar techniques of machine learning have also been used in fall detection.[7][8] Hristoskova et al.[9] propose another system wherein patient conditions are mapped to medical conditions using ontology-driven methods, and alerts are generated based on corresponding risk stratification.

Even though there has been noticeable success in detection and diagnosis of specific disease conditions, most of these works have not explored the opportunity for personalized and precision diagnosis. In an extensive review of Big Data for Health, Andreu-Perez et al.[10] specifically emphasize the opportunity for stratified patient management and personalized health diagnostics, citing examples of customized blood pressure management.[11] More specifically, Bates et al.[12] discuss the utility of using analytics to predict adverse events, which could reduce the associated morbidity and mortality rates. The authors further argue that patient data analytics based on early information supplied to the hospital prior to admission can result in better management of staffing and other hospital resources.[12] One of the recent works in personalized criticality detection is reported by Sung et al.[13], who propose an analytical unit in which the Improved Particle Swarm Optimization (IPSO) algorithm is used to arrive at patient-specific threat ranges.

To improve precision in diagnosis we also need to arrive at a balance between a completely automated system on one hand, and physician assist systems on the other. Celler et al.[14] propose a balanced approach wherein sophisticated analytics are presented to physicians, who in turn identify the changes and decide on the diagnosis. This is also supported by many results, including those reported by Skubic et al.[6], wherein domain knowledge-based methods performed as well as other trained machine learning models. These arguments and results provide further impetus for personalized, precision, and preventive diagnostic techniques that are amenable to physician interventions.

Methods

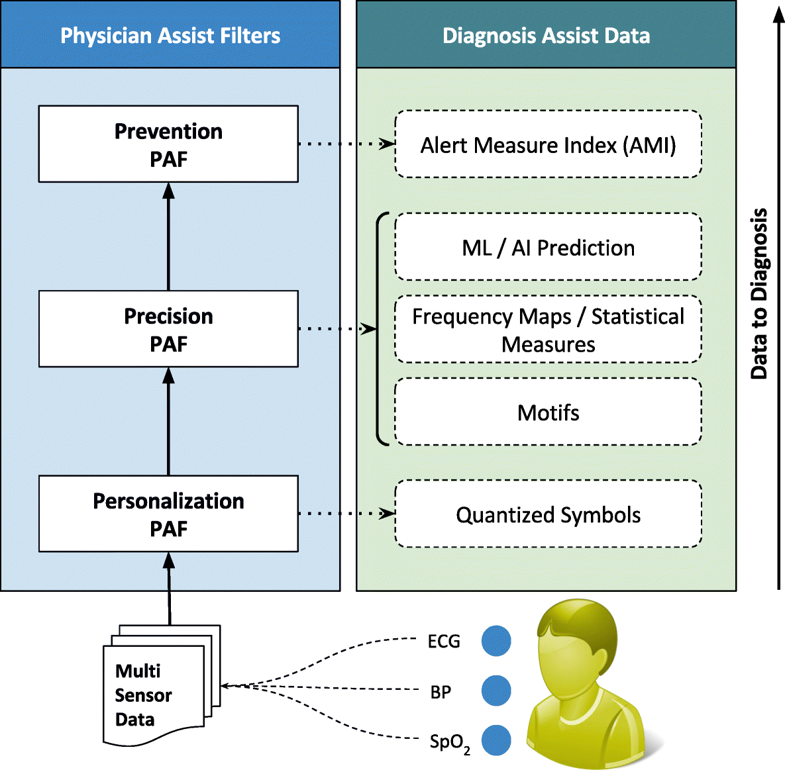

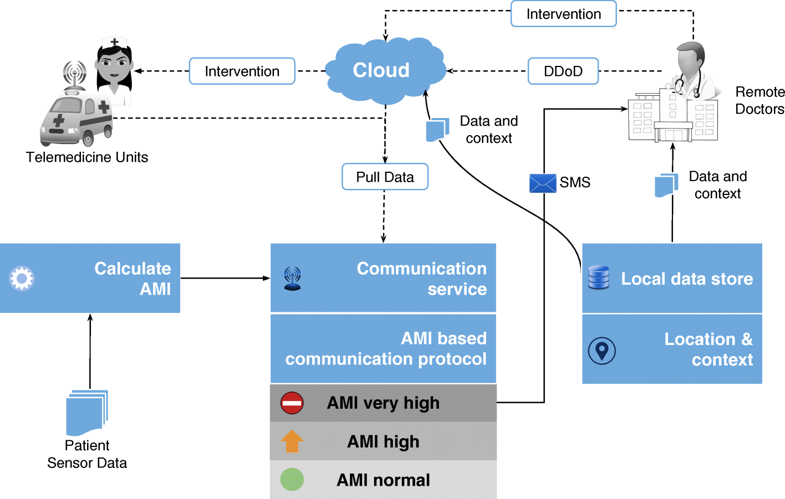

The first significant improvement that we applied is the quantization of every remotely sensed parameter based on its own customized severity boundaries. Sequential time windows of such quantized values are examined for dominant appearances of normal results or abnormalities, as the case may be, and motifs corresponding to them are extracted. Using factors set by doctors, the system then transforms these motifs by generating interventional time alerts as per clinically prescribed protocols. Both the alerts and motifs are amenable to rapid transmission to doctors, even as SMS messages on bare-minimum, bandwidth-starved wide area wireless networks. This results in the generation of more clinically relevant critical information, along with a drastic reduction in reporting every minor aberrational data that may not be indicative of any serious condition, after all. The system does not stop here. The attending doctors, when they view the alerts and/or motifs, have the luxury to request detailed data on demand (dubbed "DD-on-D"), upon which the next level of detail in the data is transmitted. This level of detail could be a straightforward frequency map of normal and abnormal values, or much more intelligent machine learning classifications in the case of proven disease conditions. The heart of our system is a framework called RASPRO (see Fig. 1), consisting of physician assist filters (PAFs) that, in going from data to diagnosis, implement the three Ps: precision, personalization, and prevention. In the following sections we describe each of these three concepts in detail.

|

Personalization PAF

Due to the distributed data gathering and processing architecture, there is an opportunity to enhance personalization in diagnosis and treatment. The first component in the RASPRO framework, the Personalization PAF takes the form of a patient- and disease-condition-specific severity quantizer that converts raw sensor values to a series of clinically relevant severity symbols.

Adaptive qauntization

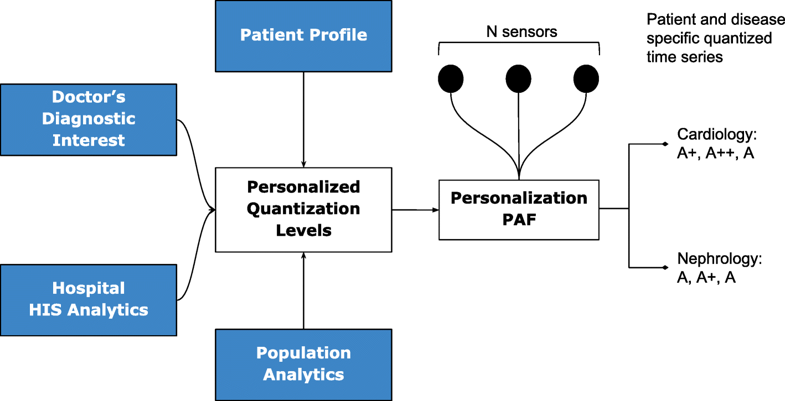

In general, let us consider N body sensors, S1,S2,…,SN with varying sensing frequencies f1,f2,…,fN. The raw time series values from these sensors are converted to discrete severity level symbols by the quantizer. The number of severity levels Li for a sensor Si can be set based on the sensor and many other factors. We assume that different vital parameter sensors have a different number of severity levels, and hence L1, say the number of severity levels for a blood pressure sensor, could be equal to five, whereas, L2 (say oxygen saturation levels) could be equal to seven. In our symbolic notation, the clinically accepted normal values are assigned the symbol "A," while above-normal values are assigned with progressive degrees of severity as "A+," "A++," etc., while that of sub-normal values are assigned "A-," "A−−," etc.; the number of “+” and “-” symbols representing degree of normal and subnormal severity respectively. Figure 2 depicts how various severity levels are arrived at in the Personalization PAF severity quantizer.

|

The quantized severity symbols are arranged into a patient-specific matrix (PSM) of N rows and W columns, where N is the total number of sensors being observed, and W is a time window in which the data is summarized. The value of W can be set by a physician or automatically derived based on the risk perception of that particular patient.

Personalization

The quantization breadth are decided by doctors based on the patient profile (or history), doctor’s diagnostic interest (for instance, a cardiologist may assign severity ranges differently from that of a nephrologist), severity ranges as suggested by using analytics on a local hospital information system (HIS), and also based on population analytics across multiple HIS spanning multiple hospitals or even from publicly available databases such as PhysioNet.[15] Together, this approach gives ample flexibility in achieving customization in inter-patient, inter-disease, intra-patient, inter-specialty diagnosis from multi-sensor data.

Precision PAF

Whereas in most other applications precision directly translates into great detail in data, in remote health monitoring, precision cannot come at a cost of voluminous data presentation to the doctor. Compactness has to be retained. We have developed a step-wise refinement process for precision, which is delivered on-demand to the attending doctor. Step 1 is “Consensus Motifs (CM)”; step 2 is a collection of statistical parameters, including severity frequency maps (SFMs); and step 3 is machine learning (ML). In the first step, motifs corresponding to commonly seen normal results and abnormalities in the severity symbols series are extracted. The outcome of this is two severity summaries: (1) the most frequent trend in sensor data that we call consensus normal motif (CNM), and (2) the most frequently occurring abnormality that we term as consensus abnormality motif (CAM). The construction of this involves the following building blocks:

- Candidate symbol: α[p] is the p-th quantized severity symbol in a row of the PSM, α[1],α[2],…,α[p],…,α[W].

- Normal symbol: αNORM is a candidate symbol that represents the normal level, and its value is equal to “A” for every sensor.

- Now, let the set Cn denote all the candidate symbols in a W-long observation window, corresponding to n-th sensor in the PSM. However, we have dropped the subscript n for better clarity of discussion.

- Let σ[p] denote the sum of hamming distances of α[p] from all other candidate symbols in C such that:

- where, D(α[p],α[i]) is the hamming distance of α[p] from α[i]. Here, we assume that the hamming distance between neighboring severity levels (say, A and A+) is 1. We define a set H of all σ’s such that:

- .

- Consensus normal symbol: αCNS[C] is defined as a candidate symbol among all the symbols in C that satisfies the following two conditions: (1) its hamming distance from the normal symbol, denoted as D(αCNS[C],αNORM), is less than a sensor specific near-normal severity threshold S[n]THRESH, and (2) its sum of hamming distances from all other candidate symbols in C is the minimum. This is formulated as:

- Consensus abnormality symbol: αCAS[C] is defined as a candidate symbol in C that satisfies the following two conditions: its hamming distance from normal symbol D(αCNS[C],αNORM) is greater than or equal to a sensor specific near-normal severity thresholdS[n]THRESH and the sum of hamming distances from all other candidate symbols in C is the minimum. This is formulated as:

- Consensus normal motif: μCNM[P] is an ordered sequence of consensus normal symbols belonging to N rows in the PSM of a patient P, and is represented as <αCNS[C1],αCNS[C2],…,αCNS[CN]>. The n-th consensus normal symbol αCNS[CN] in μCNM[P] can be indexed as μCNM[P][n].

- Consensus abnormality motif: μCAM[P] is an ordered sequence of consensus abnormality symbols belonging to N rows in the PSM of patient P, which is represented as <αCAS[C1],αCAS[C2],…,αCAS[CN]>. The n-th consensus abnormality symbol αCAS[CN] in μCAM[P] can be indexed as μCAM[P][n].

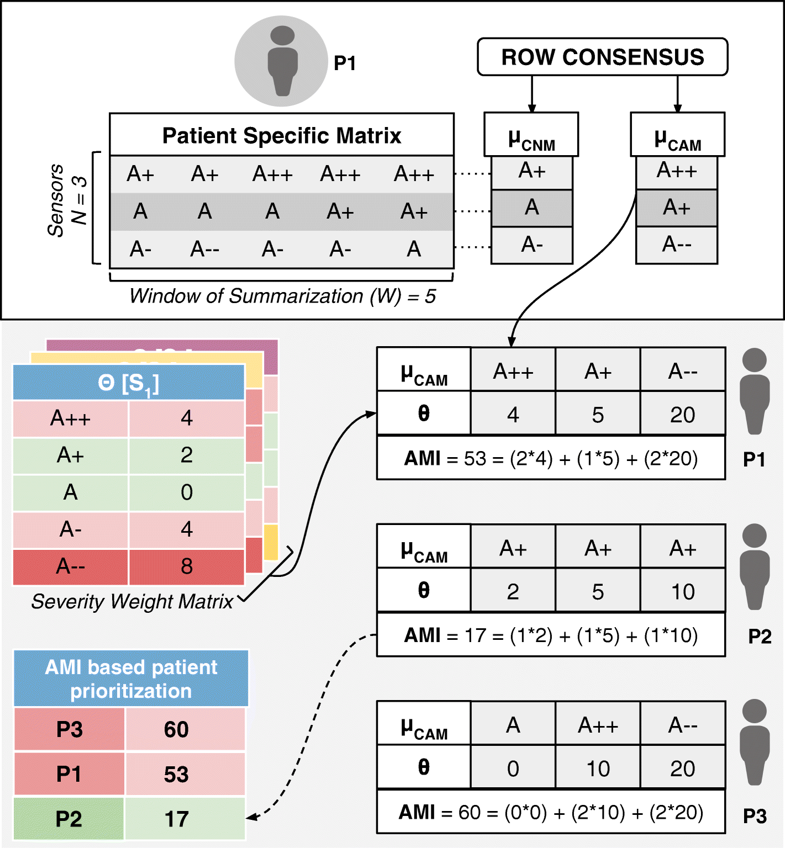

- To reiterate in the above formulation, each row of a PSM is considered as an observation window set C (corresponding to a summarization time window W) to find the corresponding consensus symbols, αCNS[C] and αCAS[C]. The sequence of these symbols over the N rows in a PSM form column vector motifs μCNM[P] and μCAM[P] (refer to Fig. 3).

|

In subsequent steps of Precision PAF, the system generates a frequency map that shows how frequently different multi-sensor parameters have crossed the personalized severity thresholds. Finally, the motif time series is further used as input to proven deep learning (DL) and machine learning (ML) techniques such as long short-term memory (LSTM) recurrent neural networks (RNN)[16] or support vector machines (SVM)[17] that could help the doctors in diagnosis. In the next section, we use the above consensus motifs for alert generation to aid in criticality prevention.

Prevention PAF

Implemented as an alert generation technique that uses simple or complex mathematical models, to calculate the amount of time available to the physicians for effective intervention, the Prevention PAF is amenable to changes based on patient, disease, and physician diagnostic interest. The output of the Prevention PAF is an alert measure index (AMI) that is used to prioritize the patients based on their urgency for physicians’ interventional attention.

Each severity symbol in a motif also communicates how much time is available with the doctor for deciding an intervention (any if needed). Hence, for each sensor S1, S2, …, SN and its corresponding severity symbol α in μCNM[P] and μCAM[P] (where α could be A, A+, A-, etc.) we associate it with a corresponding medically accepted intervention time δ[Sn][α]. Across different sensors Sn for a patient P, let us consider θ[Sn][α] as a sensor and severity symbol indexed matrix of weights derived from interventional time using the following relationship:

In the above equation, the constant KP can be set by the physician considering the context of a patient’s health condition (including historical medical records and specific sensitivities and vulnerabilities documented therein) or derived through machine learning techniques. The above equation may be substituted by more complex equations for progressively complicated disease conditions.

At the end of each observation time-window W, for every patient P, we also define an aggregate criticality alert score, called the Alert Measure Index (AMI), which is calculated as:

wherein, each severity quantized symbol in the μCAM[P] of the n-th sensor is converted into a numerical value (e.g., A± is assigned 1, A++ or A−− is assigned 2) using num(μCAM[P][n]), and scales it up by the sensor-severity specific weight θ[Sn][α] (as defined just prior). The resulting AMI is indicative of the immediacy of patient priority for physician’s consultative attention. The process of motif detection, AMI calculation, and patient prioritization is summarized in Fig. 3. The data used to arrive at the AMI scores could be other statistical parameters (such as frequency maps) or machine learning prediction scores. Also, the technique for calculating the score may also be based on predefined simple mathematical models or complex machine learning algorithms.

Clinical relevance and validation

In October 2016, the RASPRO framework was introduced to doctors in multiple specialties in our super-specialty hospital, wherein they validated its clinical deployment applications. We present some of the specific clinical scenarios that emerged from this pilot study.

Cardiology

The electrocardiogram is a potential indicator of cardiac events and can be exploited for personalized and precision diagnosis by varying the parametric thresholds and summarization window, based on patient profile/disease condition and associated factors. For instance, taking into account the disease condition, a 3mm depression in the ST segment would be graded as A++ for an active patient having exertion related chest pain, indicating cardiac ischemia, whereas the same if occurred in a patient at rest, would be graded as A+++ with limited time of intervention (30 min), indicating cardiac muscle death. To extend the spectrum of diseases that ST segment depression would cover, a chronic hypertensive with left ventricular hypertrophy of the heart (and no chest pain) would also presumably have a continuous 3mm dip in the ST segment which does not require any interventional attention, and hence, would be graded as A/A+ (near normal) by the severity quantizer. Next, taking into account the patient profile, in sedentary workers, aged above 45 having smoking habit, with high cholesterol levels and other associated risks, the thresholds will be low (A+, A++, and A+++ would be assigned to 1–2mm, 2–3mm, and above 3mm ST depression respectively), while in highly active but risk patients with age less than 45, and no previous associated history, the levels will be high (A+, A++, and A+++ would correspondingly be assigned to 2–3mm, 3–3.5mm, and above 3.5mm respectively). Also, in the former case the summarization window W (capturing how long ST depression sustains) would be 3–4 minutes (more critical), whereas in the latter it would be 7–9 minutes.

Pulmonology

Simple but vital parameters such as oxygen saturation levels in the body (SpO2), blood pressure (BP), heart rate variability (HRV), and respiratory rate variability (RRV), present in unique combinations, would facilitate differentiating between benign diseases such as interstitial lung disease/sleep apnea for which the thresholds for alert (set through the interventional time constant KP) will be fairly high, and emergencies such as pulmonary edema/pulmonary embolism (blood clot in an artery in the lung) for which the thresholds will be kept low if any of the predisposing factors such as left heart failure, pulmonary hypertension, prolonged immobilization, pregnancy, etc. are present. Hence, the physician would preset these combinations of vitals to be looked for as sequence of symbols in the CAM. Since the number of parameters that could be picked up to indicate disease are a few, it is pertinent that stepwise precision techniques such as machine learning algorithms be used for distinguishing between closely mimicking conditions. Obstructive sleep apnea and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease provide solid examples, both of which would show similar trends in SpO2, BP, HRV, and RRV. In a trial that was conducted at our hospital, we were able to achieve 99% precision in diagnosing sleep apnea from HRV using a deep learning algorithm called long short-term memory recurrent neural networks (LSTM-RNN) and is reported in one of our previous works.[16] The algorithm evaluation was done using the multi-sensor patient data from the Physionet Challenge 2000[18], which contained annotated data from 35 patients who underwent overnight sleep study.

Neurology

One of the early markers of autonomic neuropathy in epileptic patients is the discrepancy between the BP and the pulse rate of the patients. In this scenario, the severity levels of BP and pulse rate would be set accordingly (as a combination) to alert the practitioner. Suppose S1 is BP and S2 is heart rate sensor respectively. Let us say for the patient P1, μCAM[P1]=<A−−,A>, and for patient P2, μCAM[P]=<A−,A+>. In both cases, the diagnosis, alert level, and treatment vary because P1 has BP decline with no change in heart rate (critical), while P2 has a compensatory increase in heart rate, which indicates good autonomic function.

Though these are representative clinical scenarios, we found wide agreement among the doctors from other specialties too that personalization, step-wise precision, and prevention introduced through the RASPRO framework is of high utility in remote monitoring and critical alert generation.

Results and discussion

In order to quantitatively evaluate the effectiveness of RASPRO, we measure both the diagnostic ability as well as the preventive predictive power of this technique. We formulate three hypotheses and evaluate the effectiveness of RASPRO in satisfying these:

- Precision hypothesis: RASPRO consensus motif time series can replace raw sensor data time series for the task of identification/classification of specific disease conditions.

- Prevention hypothesis: RAPSRO-based consensus motifs can predict future disease condition with as much accuracy as raw sensor data time series.

- Personalization hypothesis: There exists an inter-patient variability in severity levels and summarization frequencies, which if optimized individually can result in better accuracy in predicting/classifying a specific disease condition.

By assessing the validity of the first hypotheses, we aim to evaluate the extent to which RASPRO motifs can provide precision in diagnostics. The second hypothesis evaluates the utility of RASPRO as a tool for predictive analytics in critical conditions, while the third hypothesis helps us understand if there exists a case for personalization in disease discovery and prediction.

Dataset

The first step to evaluate these hypotheses is to identify datasets that are extensive, long-term and critically significant. We used a large time series dataset from the MIMIC II database[19], which contains multiple body sensor values from over 20,000 ICU patients. This dataset consists of ECG, ABP (Arterial Blood Pressure), Heart Rate (HR), Non-obtrusive BP (NBP), SpO2, Mean Arterial BP (MAP), and other vital signs. From this, we selected a curated set of patient and control group data that contained a long time series data followed by a critical event. We selected patients with acute hypotensive episodes (AHE), which is a potentially fatal condition, found quite common in ICUs as well as caused due to postural hypotension. An AHE event is analytically identified as when MAP measurements remain below 60 mmHg for more than 30 minutes. This is a potentially fatal event and requires immediate intervention. We also made sure that the dataset provides uninterrupted MAP signal with a minimum sampling rate of one per minute, over at least three hours for both the event-patients as well as the control group. We selected a group of 35 patients (called group H) who had AHE during some time during their stay in ICU, and another 35 patients (called group G) who did not have AHE during their ICU stay. This dataset was selected from the PhysioNet[15] Challenge 2009.[20] The H dataset also had a time marker t0, after which AHE occurred in that patient within a one-hour window. Since the data was obtained from publicly available sources, we did not require getting prior approval of IRB for this work.

Evaluating precision hypothesis

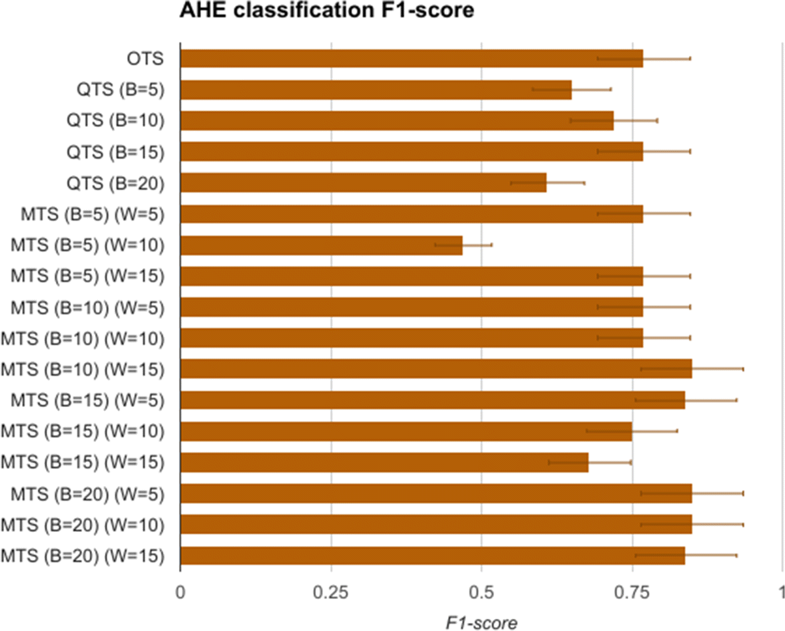

The first task is to measure the replaceability of the original time series data with the quantized symbols and consensus motifs. To evaluate this, the H and G group time series data comprising of mean arterial pressure (MAP), of length 60 minutes after t0 are modeled as feature vectors of length 60. These vectors are called original time series (OTS) and are used for training an SVM model for classifying the data as having AHE or not. The vectors belonging to AHE were labelled as H, and G otherwise. After using OTS, we then generate quantized time series (QTS) vectors with different quantization breadth. The quantization breadth (denoted by B) are varied as 5, 10, 15, and 20. For instance, when B=10, each of the OTS MAP values between 60 mmHg and 50 mmHg are quantized into the same severity symbol, say “A-,” whereas for B=5, the symbol “A-” quantizes all OTS MAP values between 60 mmHg and 55 mmHg. These vectors are used in similar manner to first train and then test the SVM model. Finally, we generate the corresponding motif time series (MTS) for each of the QTS, with varying the summarization time window W as 5, 10, and 15. The value of W corresponds to the time window in which all the severity symbols in the QTS are converted to a single consensus symbol. A comparison of OTS, QTS, and MTS is done using the statistical measure of binary classification, the F-score. An F-score (also called F1-score) is calculated as:

Significant results

The F1-scores for the SVM models are summarized in Fig. 4. It shows that OTS-based SVM model gave an F1-score of 0.76, which is the gold standard that we compare other models with. The QTS- and MTS-based SVM models were able to perform as well as OTS in most of the cases. Furthermore, MTS with (B=10 and W=15) and (B=20 and W=5,10,15) performed better than the OTS in the classification problem. In fact, these MTS models showed more than 12% better F1-score compared to OTS. These results support the precision hypothesis that motif time series can replace original time series data for the task of identification/classification of specific disease conditions, in this case AHE.

|

Evaluating prevention hypothesis

The next evaluation parameter of RASPRO is to identify if a priori motif series could predict future disease condition, and thereby aid in preventive intervention. For this, the H and G group time series data comprising of mean arterial pressure (MAP), of length T minutes prior to t0 is modeled as a T-long feature vector (OTS). These vectors are used for training (using 70% data, with five-fold cross validation) and testing (using 30% data) an SVM model for predicting them as AHE or not, where patients belonging to H group are annotated as having AHE and G group patients are annotated otherwise. In effect, we try to classify sensor data prior to an AHE event as a predictor for ensuing an AHE condition. Since G group data did not have a time marker t0, we selected a random but continuous time series of length T from each of the G group patients. SVM was selected due to its widely accepted performance in classification problems involving multiple features, although we might obtain comparable results using other classification techniques too.

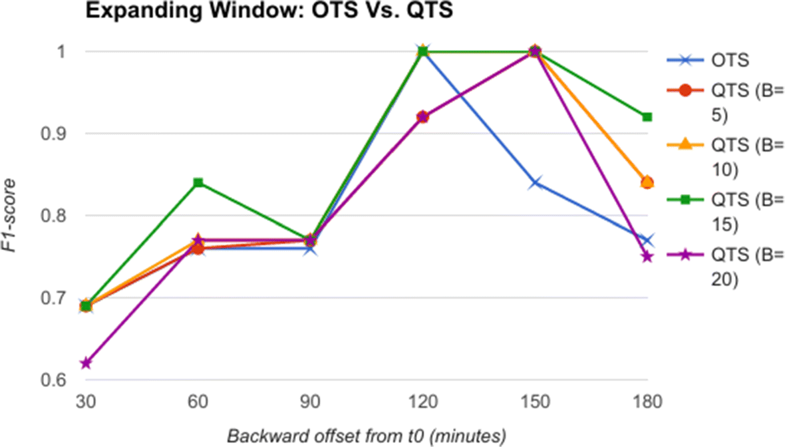

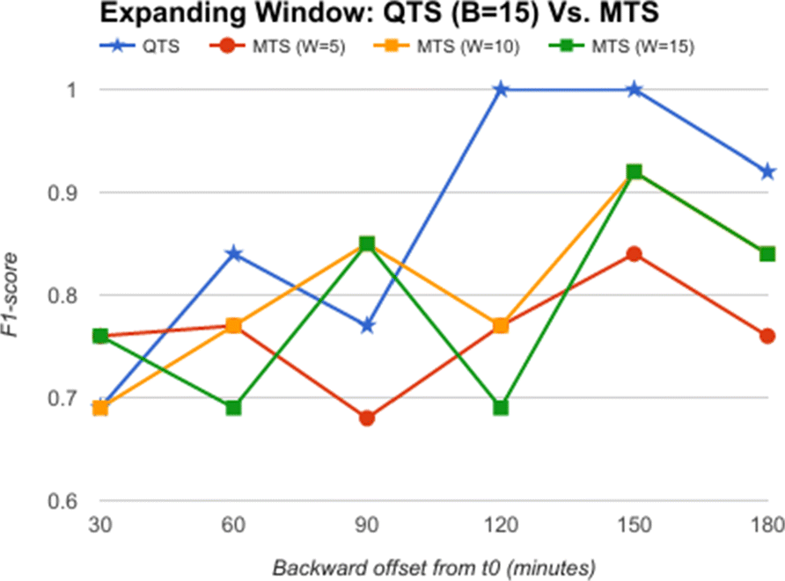

The backward offset time T (from t0) is varied as 30, 60, 90, 120, 150, and 180 minutes as an expanding window. In the next step, the raw feature vectors are quantized using severity quantizer to form a quantized time series (QTS). Once again, the quantization breadth B is varied as 5, 10, 15, and 20. In the third step, the QTS are summarized and motifs extracted to form a RASPRO motif time series (MTS), with varying observation time window sizes W: 5, 10 and 15 minutes. The QTS and MTS are then given as input to train and test the SVM model (one for QTS and another for MTS) for predicting AHE before its onset.

Significant results

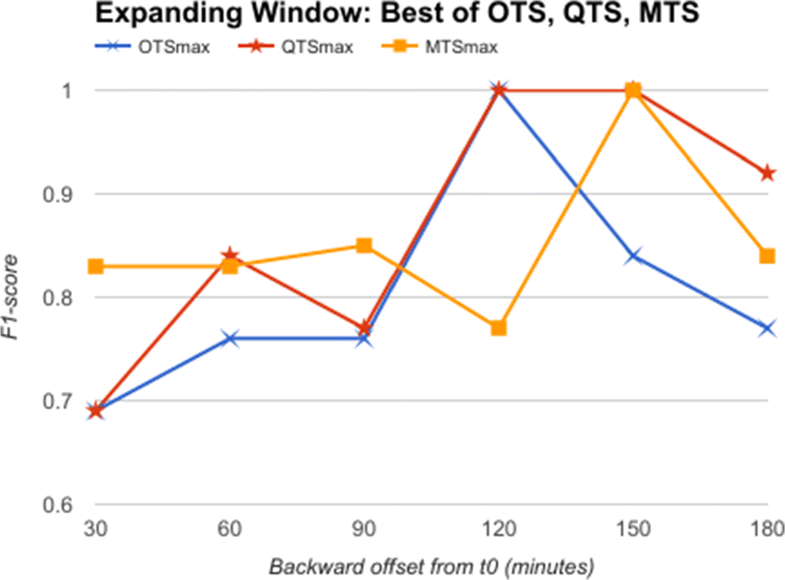

From the comparative analysis of OTS and QTS (Fig. 5), we observe that QTS with B=15 has better F1-score in comparison to OTS in all the time-offsets T, although the root mean square error (RMSE) between these two series is an insignificant 0.001, pointing to the fact that OTS could be replaced with QTS. We select this QTS (B=15) and then compare it with MTS of varying time windows in Fig. 6. We observe from Fig. 6 that QTS has a higher F1-score compared to the best MTS with W=10. However, RMSE between QTS and MTS (W=10 and W=15) is a statistically insignificant value of 0.01, which implies that MTS using W=10 and 15 performs as well as QTS on an average across different time windows. Now, we further compare the OTS against the best performing B and W values corresponding to QTS and MTS respectively, and the results are plotted in Fig. 7. These data points are marked as QTSmax and MTSmax respectively. In Fig. 7, QTSmax and MTSmax show closely similar F1-score with the RMSE as 0.018, which could be considered statistically insignificant.

|

|

|

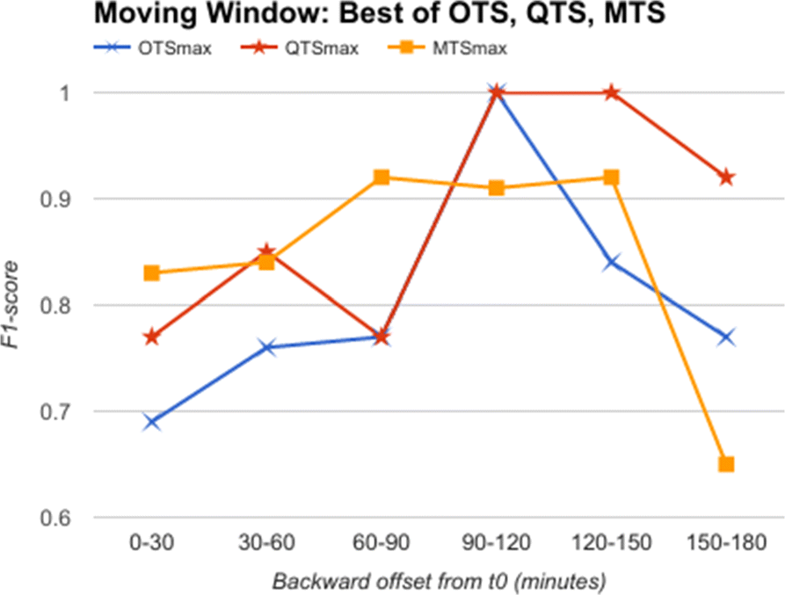

Going further, we used data from a moving time window of 30 minutes each, instead of an expanding window. This simulates the situation when we obtain data for 30 minutes alone and are required to classify it as a predictor for AHE. Here, we do not have the luxury of having data till t0, as the 30 minutes slice of data could be from anywhere up to three hours before t0. We show in Fig. 8 the comparative analysis of OTS against the best B and W values corresponding to QTS and MTS in the moving window experiment. The results plotted in Fig. 8 show that MTS and QTS perform better than OTS in most of the time intervals, while the RMSE between MTS and QTS is 0.018 on an average. The results comparing QTS with different B values against MTS with different W values are given in Additional files 1–5 (at the end of this paper).

|

From these results, we can conclude that quantized symbols, as well as summarized motifs, are as good as (or better in many cases) compared to raw time series in identifying predictors for AHE, both in expanding and moving windows, thereby supporting our prevention hypothesis.

Evaluating personalization hypothesis

The third hypothesis aims to find out if there are patient specific custom severity levels, and summarization frequencies, which if optimized could lead to better accuracy in diagnosis. For this, we further analyze our earlier results. We observe from Figs. 7 and 8 that by selecting different severity quantization breadth (B) and through varying the summarization window size (W), we are able to predict the onset of AHE with a higher F1-score. This supports an argument for using disease and time-specific B and W values for achieving better accuracy in classification problems. We observe very similar results in Fig. 4, which shows that by choosing optimized W and B values, the machine learning models can perform better in classification problems too. These results further support our third hypothesis, that there exists an opportunity for personalization at least at disease specific and time specific level. Though the above experiments using AHE are only representative of how step-wise precision, personalization, and prevention can be achieved using RASPRO, the practitioners as a whole agree that in wide-ranging scenarios patient-sensor-disease-time specific severity levels need to be defined that is both practical to manage alerts as well as effective in identifying emergencies.

Global health deployment

These medical benefits of RASPRO framework would contribute directly to fulfill the primary goals of remote health monitoring in a global health scenario. We call these benefits the "3As": availability, accessibility, and affordability.

- Availability: By enabling the doctors to prioritize their time based on the AMI, we effectively increase the availability of doctors for the neediest of remote patients.

- Accessibility: A patient’s summarized health status represented by the consensus motifs could be sent over even bare-minimum communication networks (for instance, in the form of SMS). The clinically validated RASPRO motifs would then enable the doctors to use it instead of voluminous raw sensor data for arriving at timely diagnosis. In addition, by providing step-wise precision through detailed data-on-demand (DD-on-D), the doctors can choose to get more data if needed. Together, these techniques, as illustrated in Fig. 9, increase the accessibility of patients to quality and critical remote healthcare services.

|

- Affordability: Remote health monitoring combined with timely criticality detection can substantially reduce the healthcare costs, by reducing the number of unnecessary hospital visits and smartly managing the available time of doctors who could focus on the neediest of patients. For instance, in a developing country the patients could be spending anywhere between $4-5 for travelling to the nearest hospital. Combined with the loss of their daily wages due to taking a break from their work, the cost to the patient for a hospital visit could be around $10-20 per day, not including the consultation charges (which ranges between $5-10 per visit). Through an initial survey of the patients visiting the cardiology department in our hospital it was observed that a majority of the patients do not, at the end of examination, have a cardiac disease. These could well have been diagnosed as such using remote monitoring of their vital parameters and hence avoid unnecessary hospital visits. Also, for a majority of revisiting patients, the visits could have been avoided using remote monitoring.

These advantages would help bring quality healthcare to millions of people who are currently under-served in the global health scenario. We are readying for large-scale deployment of the RASPRO framework, including the "3P" RASPRO-PAF analytical tools using a network of more than 45+ telemedicine nodes (as shown in Fig. 10) and remote health centers across the Indian sub-continent, which are connected to the AIMS hospital.

|

Practitioner education is one of the key challenges in global deployment of any new data analytics technique. To ensure usability of the system, we have involved the doctors from the design and conceptual phase of the RASPRO-PAF system. In order to provide hands-on training, acceptability, and experience in the use of the data analytics techniques, we also aim to introduce these to all the practitioners as part of the annual continuing medical education (CME) program.

Challenges and drawbacks

One of the major drawbacks of any severity detection and summarization technique is the risk of missing important data. In the RASPRO technique, we try to mitigate some of these risks by providing a graded information flow from the multiple sensors to the doctors. The alerts are calculated based on patient- and disease-specific quantization and threshold levels. Hence, the chances of generation of unnecessary alerts are low. On the other hand, upon receiving these alerts the doctors can further request for detailed data on demand (DD-on-D), using which the doctors can see actual sensor values, the calculated motifs, the frequency maps, as well as any other machine-learning-based assistive diagnosis. This provides the flexibility to doctors and emergency responders to obtain complete view of the patient condition before deciding upon any intervention. However, any such system is also fraught with the danger of system failures that could jeopardize the patient’s life, though this could be overcome to a large extent by developing robust hardware and fail-safe firmware. We are also aware that a thorough cost-risk-benefit analysis needs to be carried out before any wide scale deployment. Apart from these, in developing countries there are implementation gaps that need to be addressed which include: (a) intermittent and unreliable mobile connectivity in rural regions, (b) capturing and transmission of data while the patient is mobile, (c) power management in edge devices such as mobile phones to ensure timely processing and transmission of data, (d) whether to do the RASPRO-PAF processing at the edge or in the cloud, and (e) efficient management of remote patient monitoring through educating the support staff in hospitals.

Conclusion

In this paper, we have reported on the successful design, development, and deployment of a set of "3P" tools for healthcare data analytics, called RASPRO-PAFs that transform voluminous physiological sensor data into meaningful motifs using personalized disease severity levels. These motifs have been found to be as effective as, or in many cases better than, the raw sensor data in the identification and prediction of critical conditions in patients. Through a step-wise precision process, the doctors can gain further insight into the medical condition of the patient, progressively using quantized symbols, motifs, frequency maps, and machine learning. Furthermore, the criticality of a patient is analyzed from these motifs using a novel interventional time relationship that helps doctors prioritize their time more efficiently. Together, the 3P PAFs helps in personalized, precision, and preventive diagnosis of the patients. We have also clinically validated the efficacy of the system using both doctor feedback from the hospital as well as using machine learning techniques. Given the initial acceptance of this tool among the medical community, we are preparing for testing and evaluation in other medical domains, as well as large-scale field deployment in a global health scenario.

Abbreviations

3P: Precision, personalization, and prevention

ABP: Arterial blood pressure

AHE: Acute hypotensive episode

AIMS: Amrita institute of medical science

AMI: Alert measure index

BP: Blood pressure

CM: Consensus motifs

CAM: Consensus abnormality motif

CNM: Consensus normality motif

DD-on-D: Detailed data on demand

DL: Deep learning

ECG: Electrocardiogram

HIS: Hospital information system

HR: Heart rate

HRV: Heart rate variability

ICU: Intensive care unit

IoT: Internet of things

IPSO: Improved particle swarm optimization

LSTM: Long short term memory

MAP: Mean arterial pressure

MIMIC: Multiparameter intelligent monitoring in intensive care

ML: Machine learning

MTS: Motif time series

NBP: Non-obtrusive blood pressure

OTS: Original time series

PAF: Physician assist filter

PSM: Patient specific matrix

QTS: Quantized time series

RASPRO: Rapid active summarization for effective PROgnosis

RMSE: Root mean squared error

RRV: Respiratory rate variability

SFM: Severity frequency maps

SpO2: Peripheral capillary oxygen saturation

SVM: Support vector machine

Additional files

Additional file 1: Moving Window OTS Vs. QTS. The figure shows the F1-score while using a moving window of size 30 mins with varying backward offset from t0. The results show that QTS is always better than OTS in classifying a given window as predictor for AHE or not. (PNG 28 kb)

Additional file 2: Moving Window QTS (B=5) Vs. MTS. The figure shows the F1-score comparison of QTS with B=5 and MTS while using a moving window of size 30 mins with varying backward offset from t0. The results show that MTS is better than QTS except in two time slots. (PNG 21 kb)

Additional file 3: Moving Window QTS (B=10) Vs. MTS. The figure shows the F1-score comparison of QTS with B=10 and MTS while using a moving window of size 30 mins with varying backward offset from t0. The results show that MTS is better than QTS except in two time slots, and also W=10 and W=15 are better summarization windows. (PNG 22 kb)

Additional file 4: Moving Window QTS (B=15) Vs. MTS. The figure shows the F1-score comparison of QTS with B=15 and MTS while using a moving window of size 30 mins with varying backward offset from t0. The results show that MTS is better than QTS except in two time slots, and also W=10 and W=15 are better summarization windows. (PNG 21 kb)

Additional file 5: Moving Window QTS (B=20) Vs. MTS. The figure shows the F1-score comparison of QTS with B=20 and MTS while using a moving window of size 30 mins with varying backward offset from t0. The results show that QTS is marginally better than MTS in four time slots. (PNG 22 kb)

Declarations

Acknowledgements

We deeply thank the support and inspiration provided by the Chancellor of Amrita University, Mata Amritanandamayi Devi (known as “Amma”). This project has materialized due to her constant guidance. We also thank Dr. P Venkat Rangan, who has contributed to the idea of 3P platform as well as gave important inputs to the manuscript. We thank the doctors at AIMS hospital, who has helped us in initial clinical use case analysis of the system.

Funding

This work was not supported by any funding organization and hence not applicable.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets analysed during the current study are available in the MIMIC II Waveform repository: https://physionet.org/physiobank/database/mimic2db/.

Authors’ contributions

RKP and ESR designed the RASPRO-PAF 3P architecture. RKP analyzed and interpretted the results, and was also a major contributor in writing the manuscript. PD conducted the experiments and analysed the results. ESR interpretted and applied the algorithms on clinical cases, and was also a major contributor in writing the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The data used in this study was obtained from a publicly available anonymized dataset, the MIMIC II Waveform repository, and hence did not require any independent/separate ethics approval or consent to participate from any of the patients.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

References

- ↑ Pathinarupothi, R.K.; Rangan, E.S.; Alangot, B. et al. (2016). "RASPRO: Rapid summarization for effective prognosis in wireless remote health monitoring". 2016 IEEE Wireless Health: 1–6. doi:10.1109/WH.2016.7764566.

- ↑ Anliker, U.; Ward, J.A.; Lukowicz, P. (2004). "AMON: A wearable multiparameter medical monitoring and alert system". IEEE Transactions on Information Technology in Biomedicine 8 (4): 415–27. PMID 15615032.

- ↑ Baig, M.M.; GholamHosseini, H.; Connolly, M.J. et al. (2014). "Real-time vital signs monitoring and interpretation system for early detection of multiple physical signs in older adults". Proceeding from the IEEE-EMBS International Conference on Biomedical and Health Informatics: 355–8. doi:10.1109/BHI.2014.6864376.

- ↑ Rajevenceltha, J.; Kumar, C.S.; Kimar, A.A. (2016). "Improving the performance of multi-parameter patient monitors using feature mapping and decision fusion". Proceedings from the 2016 IEEE Region 10 Conference: 1515–8. doi:10.1109/TENCON.2016.7848268.

- ↑ Sreejith, S.; Rahul, S.; Jisha, R.C. (2016). "A Real Time Patient Monitoring System for Heart Disease Prediction Using Random Forest Algorithm". Advances in Signal Processing and Intelligent Recognition Systems 425: 485–500. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-28658-7_41.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Skubic, M.; Guevara, R.D.; Rantz, M. (2015). "Automated Health Alerts Using In-Home Sensor Data for Embedded Health Assessment". IEEE Journal of Translational Engineering in Health and Medicine 3: 1–11. doi:10.1109/JTEHM.2015.2421499.

- ↑ Lopes. I.C.; Vaidya, B.; Rodrigues, J.J.P.C. (2013). "Towards an autonomous fall detection and alerting system on a mobile and pervasive environment". Telecommunications Systems 52 (4): 2299–310. doi:10.1007/s11235-011-9534-0.

- ↑ Balasubramanian, A.; Wang, J.; Prabhakaran, B. (2016). "Discovering Multidimensional Motifs in Physiological Signals for Personalized Healthcare". EEE Journal of Selected Topics in Signal Processing 10 (5): 832–41. doi:10.1109/JSTSP.2016.2543679.

- ↑ Hristoskova, A.; Sakkalis, V.; Zacharioudakis, G. et al. (2014). "Ontology-driven monitoring of patient's vital signs enabling personalized medical detection and alert". Sensors 14 (1): 1598-628. doi:10.3390/s140101598. PMC PMC3926628. PMID 24445411. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3926628.

- ↑ Andreu-Perez, J.; Poon, C.C.; Merrifield, R.D. et al. (2015). "Big data for health". IEEE Journal of Biomedical and Health Informatics 19 (4): 1193-208. doi:10.1109/JBHI.2015.2450362. PMID 26173222.

- ↑ Liu, Q.; Yan, B.P.; Yu, C.M. et al. (2014). "Attenuation of systolic blood pressure and pulse transit time hysteresis during exercise and recovery in cardiovascular patients". IEEE Transactions on Bio-medical engineering 61 (2): 346–52. doi:10.1109/TBME.2013.2286998. PMID 24158470.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 Bates, D.W.; Saria, S.; Ohno-Machado, L. et al. (2014). "Big data in health care: using analytics to identify and manage high-risk and high-cost patients". Health Affairs 33 (7): 1123-31. doi:10.1377/hlthaff.2014.0041. PMID 25006137.

- ↑ Sung, W.-T.; Chen, J.-H.; Chang, K.-W. (2014). "Mobile Physiological Measurement Platform With Cloud and Analysis Functions Implemented via IPSO". IEEE Sensors Journal 14 (1): 111–23. doi:10.1109/JSEN.2013.2280398.

- ↑ Celler, B.G.; Sparks, R.S. (2015). "Home telemonitoring of vital signs--technical challenges and future directions". IEEE Journal of Biomedical and Health Informatics 19 (1): 82–91. doi:10.1109/JBHI.2014.2351413. PMID 25163076.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 Goldberger, A.L.; Amaral, L.A.; Glass, L. (2000). "PhysioBank, PhysioToolkit, and PhysioNet". Circulation 101 (23): e215–e220. doi:10.1161/01.CIR.101.23.e215.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 Pathinarupothi, R.K.; Vinaykumar, R.; Rangan, E. et al. (2017). "Instantaneous heart rate as a robust feature for sleep apnea severity detection using deep learning". Proceedings from the 2017 IEEE EMBS International Conference on Biomedical & Health Informatics: 293–6. doi:10.1109/BHI.2017.7897263.

- ↑ Arunan, A.; Pathinarupothi, R.K.; Ramesh, M.V. (2016). "A real-time detection and warning of cardiovascular disease LAHB for a wearable wireless ECG device". Proceedings from the 2016 IEEE-EMBS International Conference on Biomedical and Health Informatics: 98–101. doi:10.1109/BHI.2016.7455844.

- ↑ Penzel, T.; Moody, G.B.; Mark, R.G. et al. (2000). "The Apnea-ECG Database". Proceedings from Computers in Cardiology 2000 27: 255–58. doi:10.1109/CIC.2000.898505.

- ↑ Saeed, M.; Villarroel, M.; Reisner, A.T. et al. (2011). "Multiparameter Intelligent Monitoring in Intensive Care II (MIMIC-II): A public-access intensive care unit database". Critical Care Medicine 39 (5): 952–60. doi:10.1097/CCM.0b013e31820a92c6. PMC PMC3124312. PMID 21283005. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3124312.

- ↑ Moody, G.B.; Lehman, L.H. (2009). "Predicting Acute Hypotensive Episodes: The 10th Annual PhysioNet/Computers in Cardiology Challenge". Computers in Cardiology 36 (5445351): 541–544. PMC PMC2937253. PMID 20842209. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2937253.

Notes

This presentation is faithful to the original, with only a few minor changes to presentation. Grammar and punctuation was edited to American English, and in some cases additional context was added to text when necessary. In some cases important information was missing from the references, and that information was added.