Journal:The impact of extraction protocol on the chemical profile of cannabis extracts from a single cultivar

| Full article title | The impact of extraction protocol on the chemical profile of cannabis extracts from a single cultivar |

|---|---|

| Journal | Scientific Reports |

| Author(s) | Bowen, Janina K.; Chaparro, Jacqueline M.; McCorkle, Alexander M.; Palumbo, Edward; Prenni, Jessica E. |

| Author affiliation(s) | Colorado State University, Charlotte’s Web Inc. |

| Primary contact | jprenni at colostate dot edu |

| Year published | 2021 |

| Volume and issue | 11 |

| Article # | 21801 |

| DOI | 10.1038/s41598-021-01378-0 |

| ISSN | 2045-2322 |

| Distribution license | Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International |

| Website | https://www.nature.com/articles/s41598-021-01378-0 |

| Download | https://www.nature.com/articles/s41598-021-01378-0.pdf (PDF) |

|

|

This article should be considered a work in progress and incomplete. Consider this article incomplete until this notice is removed. |

Abstract

The last two decades have seen a dramatic shift in cannabis legislation around the world. Cannabis products are now widely available, and commercial production and use of phytocannabinoid products is rapidly growing. However, this growth is outpacing the research needed to elucidate the therapeutic efficacy of the myriad of chemical compounds found primarily in the flower of the female Cannabis plant. This lack of research and corresponding regulation has resulted in processing methods, products, and terminology that are variable and confusing for consumers. Importantly, the impact of processing methods on the resulting chemical profile of full spectrum cannabis extracts is not well understood. As a first step in addressing this knowledge gap, we have utilized a combination of analytical approaches to characterize the broad chemical composition of a single cannabis cultivar that was processed using previously optimized and commonly used commercial extraction protocols, including alcoholic solvents and supercritical carbon dioxide. Significant variation in the bioactive chemical profile was observed in the extracts resulting from the different protocols, demonstrating the need for further research regarding the influence of processing on therapeutic efficacy, as well as the importance of labeling in the marketing of multi-component cannabis products.

Keywords: Cannabis, processing methods, extract, cultivar, chemical analysis

Introduction

Cannabis sativa L. is a pharmacologically important annual plant that produces bioactive phytocannabinoids and other secondary metabolites that have demonstrated therapeutic potential for a wide variety of human health conditions.[1][2][3][4][5] Cannabis sativa L. can be broadly divided into three categories based on genomic diversity and chemical composition.[6] Specifically, based on the analysis of 340 cannabis varieties—including grain hemp, fiber hemp, CBD hemp, marijuana, and feral populations—the distinct groups were described as:

- fiber/grain hemp with low cannabinoid content;

- cannabis with narrow leaflets (colloquially described as sativa) and high cannabinoid content (i.e., CBD hemp and marijuana); and

- cannabis with broad leaflets (colloquially described as indica) and high cannabinoid content (i.e., CBD hemp and marijuana).

Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) and cannabidiol (CBD) are the most extensively studied Cannabis sativa L.-derived phytocannabinoids and are the only compounds currently available by prescription in the United States.[7] In addition to these two major neutral phytocannabinoids, acidic versions such as tetrahydrocannabinolic acid (THCA), cannabidiolic acid (CBDA), cannabigerolic acid (CBGA), and cannabichromenic acid (CBCA); minor versions such as cannabigerol (CBG), cannabinol (CBN), and cannabichromene (CBC) ; and varinic versions such as tetrahydrocannabivarin (THCV), cannabidivarin (CBDV), and cannabigerovarin (CBGV) have also exhibited promising in vitro and in vivo results for treatment of various human health conditions.[4] For example, as reviewed by Franco et al.[4], there is preliminary evidence that these understudied bioactive compounds have anti-inflammatory, anti-microbial, anti-proliferative, anti-convulsive, and neuroprotective properties. Furthermore, these minor phytocannabinoids are emerging as potential treatment strategies for anxiety, nausea, diabetes, acne, metabolic syndrome, obesity, pain, colorectal cancer, breast cancer, and more. Finally, in addition to phytocannabinoid compounds, there are a multitude of other bioactive compounds found in cannabis, including terpenes and terpenoids[8][9][10][11][12], flavonoids[13][14], bibenzyl[15], stilbenoids[16][17], and hydroxycinnamic acids.[18][19]

There is a growing body of work exploring cannabis polypharmacy in terms of potential synergistic effects, commonly referred to as the entourage effect, that may contribute to or modulate the therapeutic properties of cannabis extracts. Synergistic effects have been proposed in research exploring combinations of phytocannabinoids[20][21], as well as other bioactive secondary metabolites such as terpenes and/or terpenoids.[22][23] This has also been shown with human endocannabinoids in vitro, though in vivo studies are notably lacking. For example, it has been demonstrated that the endocannabinoid 2-arachidonoylglycerol shows enhanced activity in the presence of 2-acylglycerol esters, which alone are inactive.[24] This effect has also been noted for organisms other than cannabis. Combining multiple terpenes from a tropical Amazonian plant was demonstrated to have a synergistic effect that was more toxic to a parasite than the terpenes alone[12], and combining multiple terpenes was more effective at inhibiting growth of a protozoa than the terpenes alone.[25] Conversely, there is also some evidence suggesting that cannabis polypharmacy could results in negative interactions or potential toxicity.[26]

Many distillate and isolate products are readily available to consumers, including those containing CBD, CBDV, CBC, CBG, CBGA, CBN, Δ8-THC, Δ9-THC, and THCV. All but Δ9-THC products can be purchased online and shipped anywhere in the United States. There has also been a surge in marketing of so called "full spectrum" products which capitalize on the idea of the synergistic entourage effect. However, because these products are not regulated by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) as dietary supplements, there is not a clear definition of what denotes a high-quality cannabis product, and phrases such as "whole plant," "full spectrum," and "broad spectrum" further muddy the waters for consumers.

The composition of a commercial cannabis extract will in large part be determined by the genetics of the starting plant material.[27] While previous work has evaluated extraction parameters with the goal of optimizing recovery of the major phytocannabinoids[28][29][30] (28,29,30), the impact of processing methodology on the comprehensive composition of full spectrum extracts is not well understood. Commonly utilized commercial extraction approaches include the use of alcoholic solvents (e.g., ethanol and isopropanol) to more advanced technologies using supercritical carbon dioxide (CO2). Solvent extraction represents the lowest cost option; however, this method runs the risk of leaving behind trace organic solvent contamination. This is more of a concern with hydrocarbon solvents such as methanol, acetone, and butane, which are toxic for human consumption. Extraction with supercritical CO2 requires investment in specialized equipment but has multiple advantages, including “tunability” by modifying temperature and pressure conditions for more precise extraction, the potential reuse of CO2[31], and the lack of any residual solvents.

Given the lack of research into the therapeutic effects of phytocannabinoids and other bioactive secondary metabolites in humans, coupled with the potential for synergistic effects and variability in commercial processing methods, there is a critical need for additional research to characterize the numerous chemical compounds found in cannabis extracts and how this chemical profile is impacted by production choices. As a first step, we have conducted a comprehensive qualitative chemical analysis of cannabis extracts from a single high-CBD cultivar generated using three previously optimized commercial extraction protocols. The results of this study lay the groundwork for evaluation of the impact of processing method on chemical variation in full-spectrum consumer products and represent an important step towards enabling industry standardization.

Results and discussion

Cannabis extracts were generated from a single proprietary cultivar using previously optimized and commonly used commercial extraction procedures, including alcoholic extraction with ethanol and isopropanol and extraction with supercritical CO2. For the latter, two fractions were generated for analysis, S1 and S2, corresponding to different pressure settings during the extraction. Each extract was analyzed using a combination of complementary analytical approaches to ensure broad chemical coverage. Overall, 41 compounds were detected and annotated by gas chromatography–mass spectrometry (GC–MS) using a non-targeted profiling approach, 15 phytocannabinoids were evaluated by ultra-high-performance liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry (UHPLC-MS/MS) using a qualitative targeted assay, and 24 elements were quantified by inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry (ICP-MS).

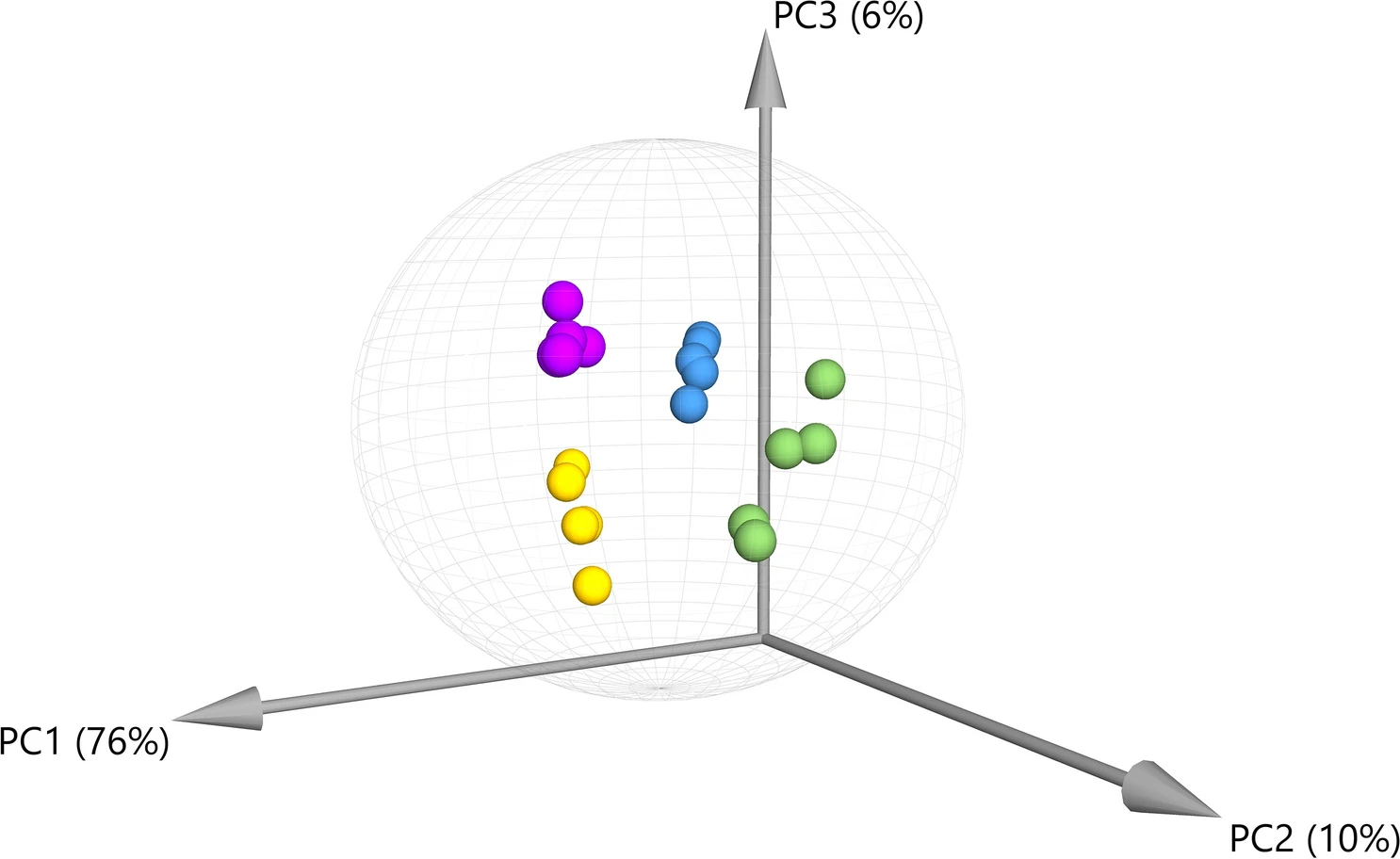

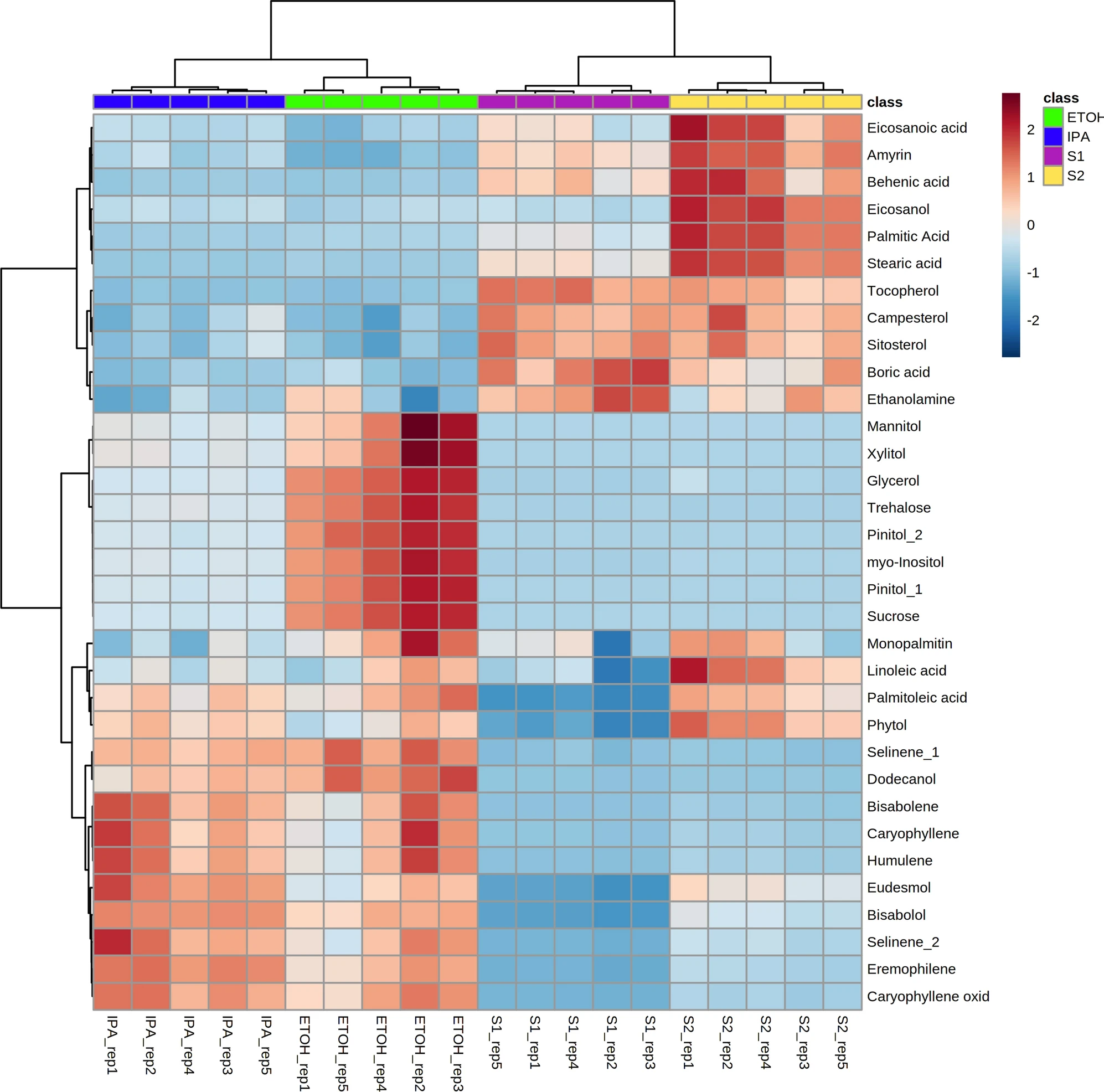

Principal component analysis (PCA) was performed for the compounds detected by GC–MS, demonstrating that there is significant variation in the overall chemical profiles between samples based on extraction method (Figure 1). Of the 41 annotated compounds detected by GC–MS, 33 were significantly different between at least two of the extracts (Supplementary Information 1, Table S1; Figure 2) (p < 0.05 after Tukey post-hoc testing for multiple comparison). These compounds include multiple long chain fatty acids, polyols and carbohydrates, and sesqui-, tri-, and diterpenoids (Supplementary Information 1, Table S2). Compound annotations were determined based on searching against spectral databases rather than comparison to authentic standards. Thus, when structural isomers could not be distinguished, annotations are denoted with a number (e.g., pinitol in Figure 2). The data reveal significant differences that could result in variation of therapeutic potential of the product (Figure 2). For example, sitosterol was significantly enriched in the S1 and S2 fractions as compared to IPA and EtOH. This compound has multiple known health benefits and is used as a potential prevention and therapy for treatment of cancer and as an anticholesteremic drug.[32] Bisabolol was significantly enriched in the IPA and EtOH extracts as compared to S1 and S2. This compound has known anti-inflammatory and anti-microbial properties.[33] Palmitoleic acid is a carboxylesterase inhibitor that has anti-inflammatory effects[34] that was enriched in the IPA, EtOH, and S2 extracts. Campesterol was enriched in the S1 and S2 extracts compared to IPA and EtOH. Plant sterols such as campesterol are cholesterol-lowering compounds[35] that may act in cancer prevention.[36]

|

|

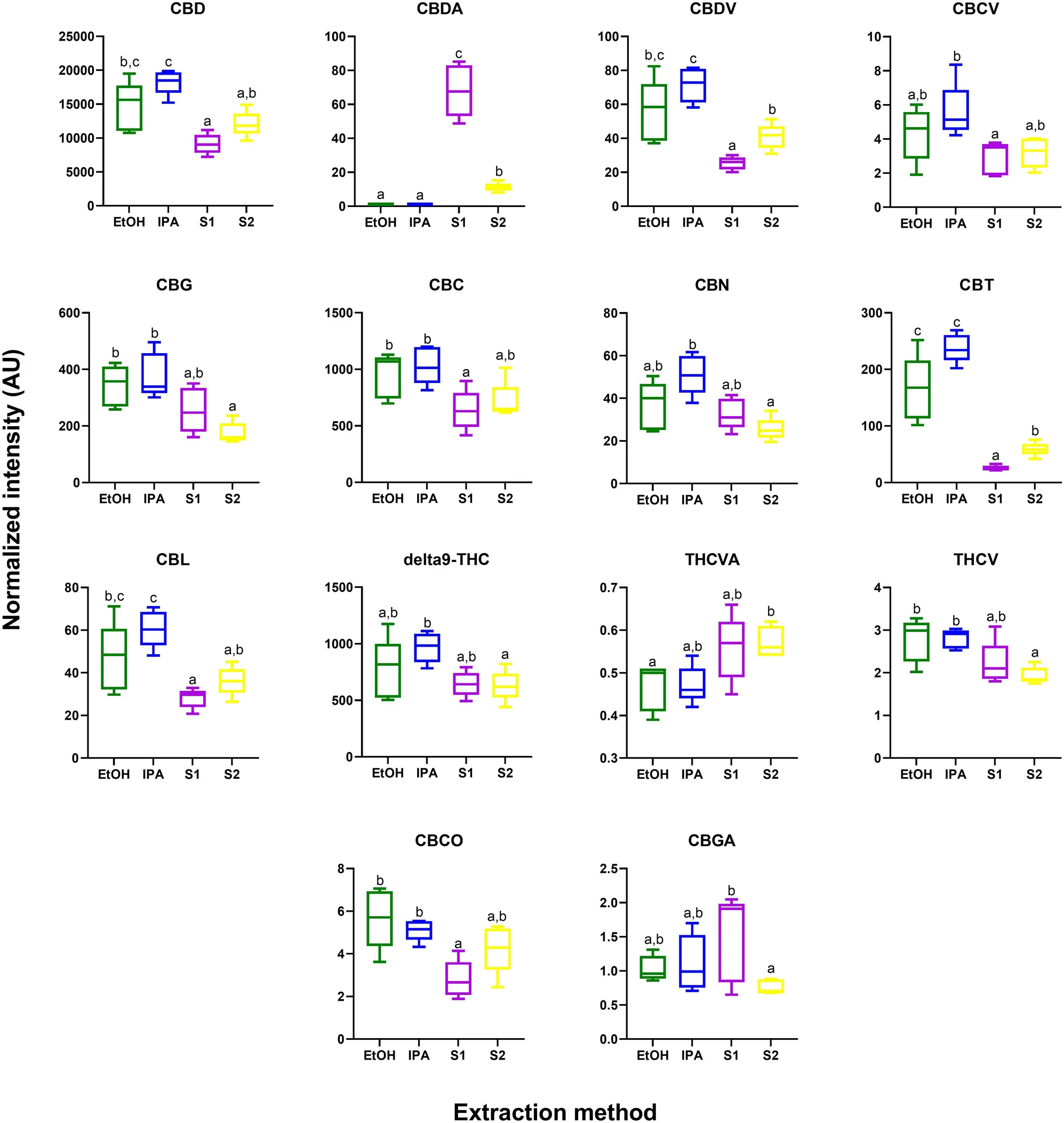

While cannabinoids were detected by GC–MS (Supplementary Information 1, Table S1), the unregulated decarboxylation that occurs in the ionization source complicates interpretation; thus, a complementary analysis was performed using a targeted UPLC-MS/MS assay. From this analysis, 14 of the 15 detected phytocannabinoids were significantly different across the extracts (Supplementary Information 1, Table S3; Figure 3) (p < 0.05 after Tukey post-hoc testing for multiple comparison).

|

In general, there is a trend of higher abundance of phytocannabinoids (including CBD and Δ9-THC) in the EtOH and IPA extracts compared to the supercritical CO2 fractions (S1 and S2). A notable break in this trend was observed for CBDA, which was observed to be in highest abundances in the supercritical CO2 S1 extract. This result could reflect incomplete decarboxylation of CBDA to CBD, which was performed by heating the dried plant material prior to extraction with supercritical CO2. This is in contrast to the process used when extracting by EtOH and IPA, where decarboxylation was performed in the liquid phase post extraction.

Interestingly, in addition to differences in the major phytocannabinoids, significant differences were observed for multiple under-researched minor phytocannabinoids. For example, CBC was observed to be significantly more abundant in the IPA and EtOH fractions as compared to S1. CBC acts as a CB2 receptor agonist that has anti-nociceptive and anti-inflammatory effects.[37][38] CBC has been implicated as a potential anti-depressant in previous in vivo studies.[39] Furthermore, CBC can act as an agonist for TRPA1 channels, as demonstrated in an ex vivo study using isolated nerves from rats.[40] It has also been implicated as an analgesic for pain localized on efferent neural pathways.[41]

The largest differences in abundance (higher in EtOH and IPA as compared to both S1 and S2) were observed for CBT, a minor phytocannabinoid found in cannabis varieties at trace levels. Intriguingly, this compound is also found in one species of rhododendron, the specific type used in traditional Chinese medicine to treat bronchitis and other respiratory ailments.[42] In one of the only in vivo studies to date, CBT was found to decrease the intraocular pressure in rabbits, suggesting CBT as a potential therapeutic for glacuoma.[43]

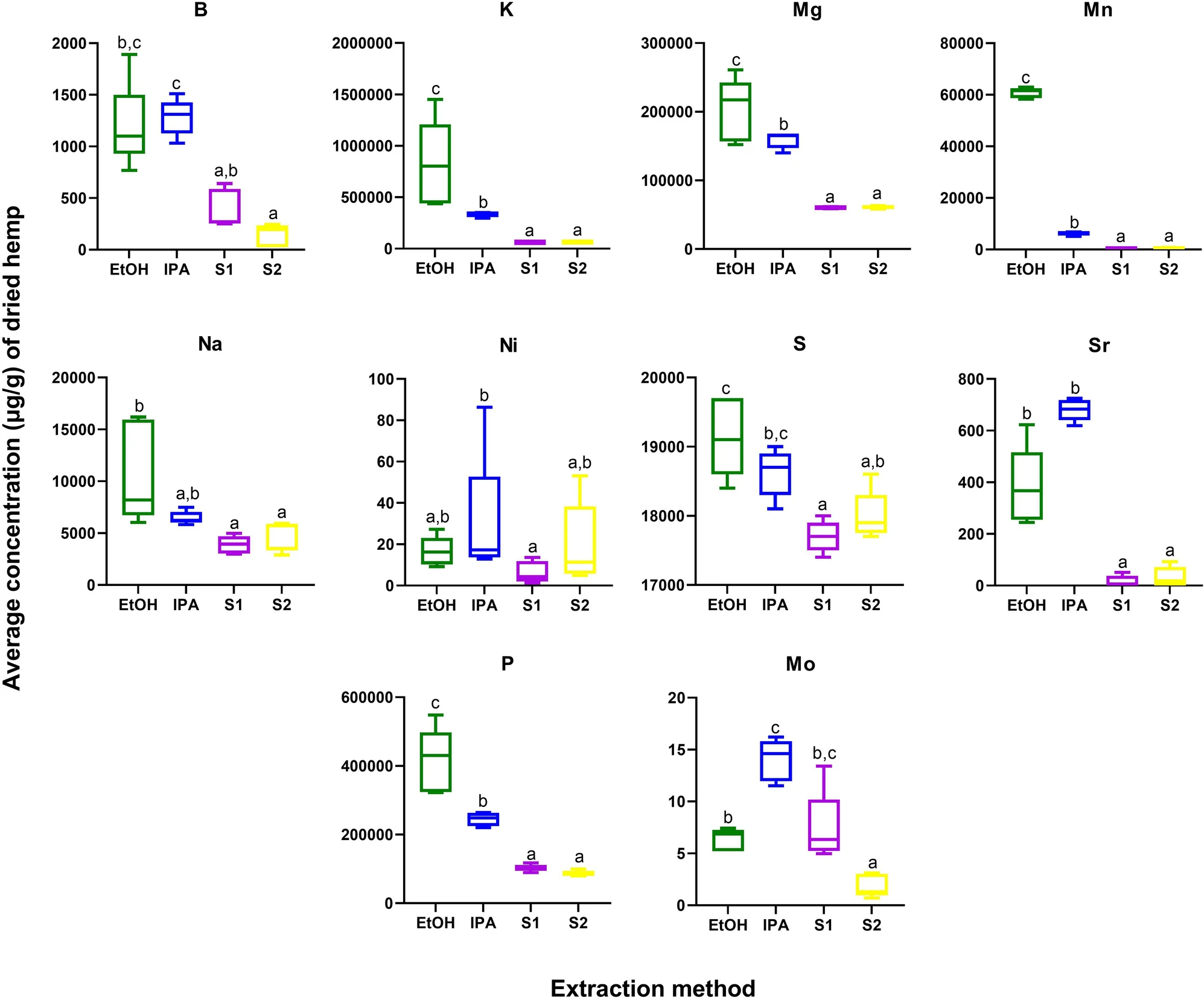

Cannabis plants have a wide root system, which can facilitate efficient uptake of elements from the soil. Cannabis products, in particular seed extracts, have been shown to be a good source of both micro- and macro-elements, including phosphorus (P), potassium (K), magnesium (Mg), calcium (Ca), iron (Fe), zinc (Zn), copper (Cu), and manganese (Mn). In addition to the absorption of beneficial nutrients, cannabis plants can also be exploited for the intentional phytoremediation of toxic heavy metals from soil.[44] Here, we performed ionomics profiling of 24 elements, including nutrients, minerals, and toxic heavy metals. Ten elements—boron (B), K, Mg, Mn, sodium (Na), nickel (Ni), sulfur (S), strontium (Sr), P, and molybdenum (Mo)—were significantly different across the four extracts, and all of these were higher in abundance in EtOH and/or IPA as compared to the supercritical CO2 fractions (Supplementary Information 1, Table S4; Figure 4). Importantly, none of the toxic heavy metals—cadmium (Cd), lead (Pb), and arsenic (As)—were significantly impacted by extraction method, and none were detected above regulatory levels set by the state of California.

|

Taken together, the results presented here highlight the importance of the extraction process in the overall chemical profile of the resulting extract, which will determine the potential bioactivity of the product. This is particularly important in the generation of so called “full spectrum,” “whole plant,” and/or “broad spectrum” extracts, which are becoming increasingly popular as consumer products but are not supported by research related to therapeutic efficacy. While comprehensive detection and characterization of all potential molecular components in a complex matrix remains a grand challenge[45], the approaches used in this study represent a relevant snapshot of the major chemical components of these extracts and lay the groundwork for future studies to explore the influence of extraction method on therapeutic potential of full spectrum products. Importantly, these results demonstrate the need for improved transparency and regulation regarding how full spectrum cannabis products are labeled to protect consumers and enable accurate interpretation and comparison of multi-component products.

Materials and methods

The use of plants in the present study complies with international, national, and institutional guidelines. Cannabis material was grown and extracted by a commercial supplier certified by the state of Colorado Department of Agriculture (Industrial Hemp Registration #102,273). All plant material (mixture of inflorescence, stem, and fan leaves) used in the three extraction methods was from a single cultivar and the same production lot. Five unique sampling replicates were used for each extraction method. The cannabis plants were air dried under ambient conditions. The dried plants (< 5% water [w/w]) were stored in the dark at 25°C prior to homogenization and extraction. Seeds, stems, and larger petioles were removed from the dried flower using a combine prior to homogenization. Material was homogenized with a hammer mill until a particle size of approximately 2–3 mm was accomplished.

Alcohol extraction

For each replicate, 7 g of dried plant material was weighed into a 100 mL media bottle. The bottle was wrapped and fully covered with aluminum foil to limit UV light exposure to the plant material inside. 75 mL of the appropriate extraction solvent—ethanol (EtOH; food-grade) or isopropyl alcohol (IPA; food-grade)—was added to each flask, followed by shaking (via flask shaker) at 150 rpm for 30 minutes at room temperature. The miscella was decanted into a tared 250 mL round bottom flask wrapped in aluminum foil. Remaining plant material was subjected to vacuum filtration (25 µm pore size). The plant material was rinsed with several 5 mL aliquots of solvent until the filtered liquid turned visibly clear. The filtrate was combined with the decanted liquid in the round bottom flask and subjected to reduced pressure evaporation at 50°C using a rotary evaporator. When the extracts were largely evaporated yet moderately viscous (as determined by visual inspection) they were transferred to 40 mL amber-colored scintillation vials incubated at 135 °C for 40 minutes for decarboxylation. After cooling to room temperature, samples were diluted with ethanol and stored at − 20°C until analysis.

Supercritical fluid extraction (SFE-CO2)

Dried plant material was heated in a 122°C conventional convection oven for 20 minutes. 1.5 kg of milled, homogenized plant biomass was placed in a supercritical CO2) extractor (Hightech Dual P-12, Biddeford, ME). The supercritical fluid was heated to 53°C and subjected to a pressure of 250 bar. The first separator (S1) was set to a pressure of 170 bar, while the second separator (S2) was set to a pressure of 70 bar; both separators were set to 53°C. The third separator pressure depended on the settings of the first two and was used as a trap for unwanted carryover substances (water) before returning back to the CO2) tank (food-grade). The flow rate was set to 45 kg CO2/hour, and the extraction cycle lasted 60 minutes. After the 60-minute cycle, two fractions were obtained through sequential depressurization from 170 Bar (S1) to system pressure (S2, 70 bar). The S1 and S2 separators were emptied of their contents and placed in several 40 mL amber scintillation vials. Extracts were homogenized, diluted with isopropyl alcohol, and stored at − 20 °C until analysis.

Extract weights from all protocols ranged from 0.31–0.80 g and were diluted to 0.05 (+ /- 0.02) g/mL in either ethanol or isopropyl alcohol prior to sample preparation as described below.

Materials for analysis

Pyridine, methoxyamine hydrochloride, N-methyl-N-trimethylsilyltrifluoroacetamide with 1% trimethylchlorosilane (MSTFA + 1% TMCS), water (LC–MS-grade), methanol (LC–MS-grade), formic acid (Pierce LC–MS-grade), and acetonitrile (LC–MS-grade) were purchased from Thermo Fisher Scientific (Waltham, MA). Twenty phytocannabinoid standards—including CBD, CBC, CBCA, CBCO, CBCV, CBDA, CBDV, CBDVA, CBG, CBGA, CBL, CBLA, CBN, CBNA, CBT, Δ9-THC, Δ8-THC, Δ9-THCA, Δ9-THCV, and Δ9-THCVA—were purchased from Cerilliant (Round Rock, TX). Single element standards for ICP-MS analysis—including aluminum (Al), As, B, barium (Ba), Ca, Cd, cobalt (Co), chromium (Cr), Cu, Fe, indium (In), iridium (Ir), K, lithium (Li), Mg, Mn, Mo, Na, Ni, P, Pb, rhodium (Rh), S, Sr, vanadium (V), tungsten (W), and Zn—were purchased from Inorganic Ventures (Christiansburg, VA).

GC-MS analysis

Non-targeted GC–MS profiling was performed using established methods as previously described by Anthony et al.[46] Briefly, 100 μL of each extract was dried under nitrogen. The dried sample was re-suspended in 90 µL of 4:4:1 MeOH:ACN:H2O, vortexed for one hour at 4°C, and then centrifuged at 12700xg for 15 minutes at 4°C. Ten microliters of the supernatant was transferred to a new vial and dried under nitrogen. The dried sample was re-suspended in 50 µL of pyridine containing 25 mg/mL of methoxyamine hydrochloride, incubated at 60˚C for one hour, sonicated for 10 minutes, and incubated for an additional one hour at 60°C. Next, 50 µL of MSTFA + 1% TMCS was added, and samples were incubated at 60°C for 45 minutes, briefly centrifuged, cooled to room temperature, and 80 µL of the supernatant was transferred to a 150 µL glass insert in a GC–MS autosampler vial. Metabolites were detected using a Trace 1310 GC coupled to a Thermo ISQ mass spectrometer (Thermo Scientific). Derivatized samples (1 µL) were injected in a 1:10 split ratio. Separation occurred using a 30 m TG-5MS column (Thermo Scientific, 0.25 mm i.d., 0.25 mm film thickness) with a 1.2 mL/min helium gas flow rate, and the program consisted of 80ºC for 30 seconds, a ramp of 15°C per min to 330°C, and an eight-minute hold. Masses between 50–650 m/z were scanned at five scans/sec after electron impact ionization.

UPLC-MS/MS analysis

Ten microliters of each extract were diluted in 990 µL of LC–MS-grade methanol. Subsequently, 10 µL of the methanol solution was diluted again to a total volume of 200 µL of LC–MS-grade MeOH. Five microliters of the final diluted extract were injected onto an LX50 UHPLC system equipped with a LX50 solvent delivery pump (20 µL sample loop, partial loop injection mode; PerkinElmer, Shelton, CT, USA). An ACQUITY UPLC HSS T3 column (1 × 100 mm, 1.8 µM; Waters Corporation, Milford, MA, USA) was used for chromatographic separation. The column was maintained at 50°C, mobile phase A consisted of LC–MS-grade water with 0.1% formic acid and mobile phase B was 100% acetonitrile. Elution gradient was initially at 59% B for 11.5 minutes, which was increased to 99% B at 16.50 minutes, then decreased to 59% B at 21.5 minutes. The column was re-equilibrated for four minutes, for a total run time of 25.50 minutes. The flow rate was set to 200 µL/min. Detection was performed on a PerkinElmer QSight 220 triple quadrupole mass spectrometer (MS) with an electrospray ionization source operated in selected reaction monitoring (SRM) switching from negative and positive mode ionization. SRM transitions for each compound were optimized through analysis of authentic standards (Supplementary Information 1, Table S5). The MS had a drying gas 120 (arbitrary units), a hot-surface induced desolvation (HSID) temperature of 250°C, electrospray voltage was kept at − 4500 eV or 4500 eV, and a nebulizer gas flow at 350 (arbitrary units). The MS acquisition was scheduled by retention time with 1.5 minute windows.

GC–MS data analysis

The GC–MS dataset was processed using the R statistics software, as described previously by Yao et al.[47] Briefly, the following processing steps were performed: (1) XCMS was used to defined a matrix of molecular features[48]; (2) data in each sample were normalized to total ion current; (3) RAMClustR package for R clustered co-varying and co-eluting features into spectra[49]; (4) RAMSearch software[50] allowed annotation by searching spectra against internal and external databases. Databases used for annotations included in-house libraries, golm, NISTv14, and MassBank. Principal component analysis (PCA) was performed using unit variance scaling in SIMCA v15.0.2 (Umetrics, Umea, Sweden). The MetaboAnalyst was used to perform hierarchical clustering using thehclustfunction in the R package stat (euclidean distance measure, ward clustering algorithm) and to generate heatmap visualization.[51] Univariate statistical analysis was performed in Prism (Version 8.2.1, GraphPad). Data was log transformed and then analyzed using a one way ANOVA with a Tukey’s multiple comparisons test.

References

- ↑ Whiting, Penny F.; Wolff, Robert F.; Deshpande, Sohan; Di Nisio, Marcello; Duffy, Steven; Hernandez, Adrian V.; Keurentjes, J. Christiaan; Lang, Shona et al. (23 June 2015). "Cannabinoids for Medical Use: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis" (in en). JAMA 313 (24): 2456–73. doi:10.1001/jama.2015.6358. ISSN 0098-7484. http://jama.jamanetwork.com/article.aspx?doi=10.1001/jama.2015.6358.

- ↑ Larsen, Christian; Shahinas, Jorida (2020). "Dosage, Efficacy and Safety of Cannabidiol Administration in Adults: A Systematic Review of Human Trials" (in en). Journal of Clinical Medicine Research 12 (3): 129–141. doi:10.14740/jocmr4090. ISSN 1918-3003. PMC PMC7092763. PMID 32231748. http://www.jocmr.org/index.php/JOCMR/article/view/4090.

- ↑ Ferber, Sari Goldstein; Namdar, Dvora; Hen-Shoval, Danielle; Eger, Gilad; Koltai, Hinanit; Shoval, Gal; Shbiro, Liat; Weller, Aron (23 January 2020). "The “Entourage Effect”: Terpenes Coupled with Cannabinoids for the Treatment of Mood Disorders and Anxiety Disorders" (in en). Current Neuropharmacology 18 (2): 87–96. doi:10.2174/1570159X17666190903103923. PMC PMC7324885. PMID 31481004. http://www.eurekaselect.com/174648/article.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 Franco, Rafael; Rivas-Santisteban, Rafael; Reyes-Resina, Irene; Casanovas, Mireia; Pérez-Olives, Catalina; Ferreiro-Vera, Carlos; Navarro, Gemma; Sánchez de Medina, Verónica et al. (1 August 2020). "Pharmacological potential of varinic-, minor-, and acidic phytocannabinoids" (in en). Pharmacological Research 158: 104801. doi:10.1016/j.phrs.2020.104801. https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S1043661820311099.

- ↑ Gonçalves, Joana; Rosado, Tiago; Soares, Sofia; Simão, Ana; Caramelo, Débora; Luís, Ângelo; Fernández, Nicolás; Barroso, Mário et al. (23 February 2019). "Cannabis and Its Secondary Metabolites: Their Use as Therapeutic Drugs, Toxicological Aspects, and Analytical Determination" (in en). Medicines 6 (1): 31. doi:10.3390/medicines6010031. ISSN 2305-6320. PMC PMC6473697. PMID 30813390. http://www.mdpi.com/2305-6320/6/1/31.

- ↑ Lynch, Ryan C.; Vergara, Daniela; Tittes, Silas; White, Kristin; Schwartz, C. J.; Gibbs, Matthew J.; Ruthenburg, Travis C.; deCesare, Kymron et al. (1 November 2016). "Genomic and Chemical Diversity in Cannabis" (in en). Critical Reviews in Plant Sciences 35 (5-6): 349–363. doi:10.1080/07352689.2016.1265363. ISSN 0735-2689. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/07352689.2016.1265363.

- ↑ National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health (November 2019). "Cannabis (Marijuana) and Cannabinoids: What You Need To Know". U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. https://www.nccih.nih.gov/health/cannabis-marijuana-and-cannabinoids-what-you-need-to-know.

- ↑ Andrade-Ochoa, S.; Correa-Basurto, J.; Rodríguez-Valdez, L. M.; Sánchez-Torres, L. E.; Nogueda-Torres, B.; Nevárez-Moorillón, G. V. (1 December 2018). "In vitro and in silico studies of terpenes, terpenoids and related compounds with larvicidal and pupaecidal activity against Culex quinquefasciatus Say (Diptera: Culicidae)" (in en). Chemistry Central Journal 12 (1): 53. doi:10.1186/s13065-018-0425-2. ISSN 1752-153X. PMC PMC5945571. PMID 29748726. https://bmcchem.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s13065-018-0425-2.

- ↑ Campos-Xolalpa, Nimsi; Pérez-Gutiérrez, Salud; Pérez-González, Cuauhtémoc; Mendoza-Pérez, Julia; Alonso-Castro, Angel Josabad (2018), Akhtar, Mohd Sayeed; Swamy, Mallappa Kumara, eds., "Terpenes of the Genus Salvia: Cytotoxicity and Antitumoral Effects" (in en), Anticancer Plants: Natural Products and Biotechnological Implements (Singapore: Springer Singapore): 163–205, doi:10.1007/978-981-10-8064-7_8, ISBN 978-981-10-8063-0, http://link.springer.com/10.1007/978-981-10-8064-7_8

- ↑ Angelini, Paola; Tirillini, Bruno; Akhtar, Mohd Sayeed; Dimitriu, Luminita; Bricchi, Emma; Bertuzzi, Gianluigi; Venanzoni, Roberto (2018), Akhtar, Mohd Sayeed; Swamy, Mallappa Kumara, eds., "Essential Oil with Anticancer Activity: An Overview" (in en), Anticancer Plants: Natural Products and Biotechnological Implements (Singapore: Springer Singapore): 207–231, doi:10.1007/978-981-10-8064-7_9, ISBN 978-981-10-8063-0, http://link.springer.com/10.1007/978-981-10-8064-7_9

- ↑ Marques, Franciane Martins; Figueira, Mariana Moreira; Schmitt, Elisângela Flávia Pimentel; Kondratyuk, Tamara P.; Endringer, Denise Coutinho; Scherer, Rodrigo; Fronza, Marcio (1 April 2019). "In vitro anti-inflammatory activity of terpenes via suppression of superoxide and nitric oxide generation and the NF-κB signalling pathway" (in en). Inflammopharmacology 27 (2): 281–289. doi:10.1007/s10787-018-0483-z. ISSN 0925-4692. http://link.springer.com/10.1007/s10787-018-0483-z.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 Izumi, Erika; Ueda-Nakamura, Tânia; Veiga, Valdir F.; Pinto, Angelo C.; Nakamura, Celso Vataru (12 April 2012). "Terpenes from Copaifera Demonstrated in Vitro Antiparasitic and Synergic Activity" (in en). Journal of Medicinal Chemistry 55 (7): 2994–3001. doi:10.1021/jm201451h. ISSN 0022-2623. https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/jm201451h.

- ↑ Eggers, Carly; Fujitani, Masaya; Kato, Ryuji; Smid, Scott (1 November 2019). "Novel cannabis flavonoid, cannflavin A displays both a hormetic and neuroprotective profile against amyloid β-mediated neurotoxicity in PC12 cells: Comparison with geranylated flavonoids, mimulone and diplacone" (in en). Biochemical Pharmacology 169: 113609. doi:10.1016/j.bcp.2019.08.011. https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0006295219302990.

- ↑ Barrett, M.L.; Gordon, D.; Evans, F.J. (1 June 1985). "Isolation from cannabis sativa L. of cannflavin—a novel inhibitor of prostaglandin production" (in en). Biochemical Pharmacology 34 (11): 2019–2024. doi:10.1016/0006-2952(85)90325-9. https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/0006295285903259.

- ↑ Allegrone, Gianna; Pollastro, Federica; Magagnini, Gianmaria; Taglialatela-Scafati, Orazio; Seegers, Julia; Koeberle, Andreas; Werz, Oliver; Appendino, Giovanni (24 March 2017). "The Bibenzyl Canniprene Inhibits the Production of Pro-Inflammatory Eicosanoids and Selectively Accumulates in Some Cannabis sativa Strains" (in en). Journal of Natural Products 80 (3): 731–734. doi:10.1021/acs.jnatprod.6b01126. ISSN 0163-3864. https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acs.jnatprod.6b01126.

- ↑ Guo, Tiantian; Liu, Qingchao; Hou, Pengbo; Li, Fahui; Guo, Shoudong; Song, Weiguo; Zhang, Hai; Liu, Xueying et al. (2018). "Stilbenoids and cannabinoids from the leaves of Cannabis sativa f. sativa with potential reverse cholesterol transport activity" (in en). Food & Function 9 (12): 6608–6617. doi:10.1039/C8FO01896K. ISSN 2042-6496. http://xlink.rsc.org/?DOI=C8FO01896K.

- ↑ Andre, Christelle; Larondelle, Yvan; Evers, Daniele (1 February 2010). "Dietary Antioxidants and Oxidative Stress from a Human and Plant Perspective: A Review" (in en). Current Nutrition & Food Science 6 (1): 2–12. doi:10.2174/157340110790909563. http://www.eurekaselect.com/openurl/content.php?genre=article&issn=1573-4013&volume=6&issue=1&spage=2.

- ↑ Taofiq, Oludemi; González-Paramás, Ana; Barreiro, Maria; Ferreira, Isabel (13 February 2017). "Hydroxycinnamic Acids and Their Derivatives: Cosmeceutical Significance, Challenges and Future Perspectives, a Review" (in en). Molecules 22 (2): 281. doi:10.3390/molecules22020281. ISSN 1420-3049. PMC PMC6155946. PMID 28208818. http://www.mdpi.com/1420-3049/22/2/281.

- ↑ Candy, Laure; Bassil, Sabina; Rigal, Luc; Simon, Valerie; Raynaud, Christine (1 December 2017). "Thermo-mechano-chemical extraction of hydroxycinnamic acids from industrial hemp by-products using a twin-screw extruder" (in en). Industrial Crops and Products 109: 335–345. doi:10.1016/j.indcrop.2017.08.044. https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0926669017305551.

- ↑ Russo, Ethan B. (9 January 2019). "The Case for the Entourage Effect and Conventional Breeding of Clinical Cannabis: No “Strain,” No Gain". Frontiers in Plant Science 9: 1969. doi:10.3389/fpls.2018.01969. ISSN 1664-462X. PMC PMC6334252. PMID 30687364. https://www.frontiersin.org/article/10.3389/fpls.2018.01969/full.

- ↑ Nallathambi, Rameshprabu; Mazuz, Moran; Namdar, Dvory; Shik, Michal; Namintzer, Diana; Vinayaka, Ajjampura C.; Ion, Aurel; Faigenboim, Adi et al. (1 June 2018). "Identification of Synergistic Interaction Between Cannabis-Derived Compounds for Cytotoxic Activity in Colorectal Cancer Cell Lines and Colon Polyps That Induces Apoptosis-Related Cell Death and Distinct Gene Expression" (in en). Cannabis and Cannabinoid Research 3 (1): 120–135. doi:10.1089/can.2018.0010. ISSN 2378-8763. PMC PMC6038055. PMID 29992185. http://www.liebertpub.com/doi/10.1089/can.2018.0010.

- ↑ Russo, Ethan B (1 August 2011). "Taming THC: potential cannabis synergy and phytocannabinoid-terpenoid entourage effects: Phytocannabinoid-terpenoid entourage effects" (in en). British Journal of Pharmacology 163 (7): 1344–1364. doi:10.1111/j.1476-5381.2011.01238.x. PMC PMC3165946. PMID 21749363. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1476-5381.2011.01238.x.

- ↑ Koltai, Hinanit; Poulin, Patrick; Namdar, Dvory (1 April 2019). "Promoting cannabis products to pharmaceutical drugs" (in en). European Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences 132: 118–120. doi:10.1016/j.ejps.2019.02.027. https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0928098719300880.

- ↑ Ben-Shabat, Shimon; Fride, Ester; Sheskin, Tzviel; Tamiri, Tsippy; Rhee, Man-Hee; Vogel, Zvi; Bisogno, Tiziana; De Petrocellis, Luciano et al. (1 July 1998). "An entourage effect: inactive endogenous fatty acid glycerol esters enhance 2-arachidonoyl-glycerol cannabinoid activity" (in en). European Journal of Pharmacology 353 (1): 23–31. doi:10.1016/S0014-2999(98)00392-6. https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0014299998003926.

- ↑ Azeredo, Camila M.O.; Soares, Maurilio J. (1 September 2013). "Combination of the essential oil constituents citral, eugenol and thymol enhance their inhibitory effect on Crithidia fasciculata and Trypanosoma cruzi growth" (in en). Revista Brasileira de Farmacognosia 23 (5): 762–768. doi:10.1590/S0102-695X2013000500007. https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0102695X13701029.

- ↑ Cogan, Peter S. (2 August 2020). "The ‘entourage effect’ or ‘hodge-podge hashish’: the questionable rebranding, marketing, and expectations of cannabis polypharmacy" (in en). Expert Review of Clinical Pharmacology 13 (8): 835–845. doi:10.1080/17512433.2020.1721281. ISSN 1751-2433. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/17512433.2020.1721281.

- ↑ Campbell, Brian J.; Berrada, Abdel F.; Hudalla, Chris; Amaducci, Stefano; McKay, John K. (1 January 2019). "Genotype × Environment Interactions of Industrial Hemp Cultivars Highlight Diverse Responses to Environmental Factors" (in en). Agrosystems, Geosciences & Environment 2 (1): 1–11. doi:10.2134/age2018.11.0057. ISSN 2639-6696. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.2134/age2018.11.0057.

- ↑ Grijó, Daniel Ribeiro; Vieitez Osorio, Ignacio Alberto; Cardozo-Filho, Lúcio (1 December 2018). "Supercritical extraction strategies using CO2 and ethanol to obtain cannabinoid compounds from Cannabis hybrid flowers" (in en). Journal of CO2 Utilization 28: 174–180. doi:10.1016/j.jcou.2018.09.022. https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S2212982018304220.

- ↑ Ribeiro Grijó, Daniel; Lazarin Bidoia, Danielle; Vataru Nakamura, Celso; Vieitez Osorio, Ignacio; Cardozo-Filho, Lúcio (1 July 2019). "Analysis of the antitumor activity of bioactive compounds of Cannabis flowers extracted by green solvents" (in en). The Journal of Supercritical Fluids 149: 20–25. doi:10.1016/j.supflu.2019.03.012. https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0896844618307812.

- ↑ Rochfort, Simone; Isbel, Ashley; Ezernieks, Vilnis; Elkins, Aaron; Vincent, Delphine; Deseo, Myrna A.; Spangenberg, German C. (1 December 2020). "Utilisation of Design of Experiments Approach to Optimise Supercritical Fluid Extraction of Medicinal Cannabis" (in en). Scientific Reports 10 (1): 9124. doi:10.1038/s41598-020-66119-1. ISSN 2045-2322. PMC PMC7272408. PMID 32499550. http://www.nature.com/articles/s41598-020-66119-1.

- ↑ Perrotin-Brunel, Helene; Kroon, Maaike C.; van Roosmalen, Maaike J.E.; van Spronsen, Jaap; Peters, Cor J.; Witkamp, Geert-Jan (1 December 2010). "Solubility of non-psychoactive cannabinoids in supercritical carbon dioxide and comparison with psychoactive cannabinoids" (in en). The Journal of Supercritical Fluids 55 (2): 603–608. doi:10.1016/j.supflu.2010.09.011. https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0896844610003013.

- ↑ Rudkowska, Iwona; AbuMweis, Suhad S.; Nicolle, Catherine; Jones, Peter J.H. (1 October 2008). "Cholesterol-Lowering Efficacy of Plant Sterols in Low-Fat Yogurt Consumed as a Snack or with a Meal" (in en). Journal of the American College of Nutrition 27 (5): 588–595. doi:10.1080/07315724.2008.10719742. ISSN 0731-5724. http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/07315724.2008.10719742.

- ↑ Kamatou, Guy P. P.; Viljoen, Alvaro M. (1 January 2010). "A Review of the Application and Pharmacological Properties of α-Bisabolol and α-Bisabolol-Rich Oils" (in en). Journal of the American Oil Chemists' Society 87 (1): 1–7. doi:10.1007/s11746-009-1483-3. ISSN 0003-021X. http://doi.wiley.com/10.1007/s11746-009-1483-3.

- ↑ de Souza, Camila Oliveira; Valenzuela, Carina A.; Baker, Ella J.; Miles, Elizabeth A.; Rosa Neto, José C.; Calder, Philip C. (1 October 2018). "Palmitoleic Acid has Stronger Anti-Inflammatory Potential in Human Endothelial Cells Compared to Oleic and Palmitic Acids" (in en). Molecular Nutrition & Food Research 62 (20): 1800322. doi:10.1002/mnfr.201800322. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/mnfr.201800322.

- ↑ Heggen, E.; Granlund, L.; Pedersen, J.I.; Holme, I.; Ceglarek, U.; Thiery, J.; Kirkhus, B.; Tonstad, S. (1 May 2010). "Plant sterols from rapeseed and tall oils: Effects on lipids, fat-soluble vitamins and plant sterol concentrations" (in en). Nutrition, Metabolism and Cardiovascular Diseases 20 (4): 258–265. doi:10.1016/j.numecd.2009.04.001. https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0939475309000957.

- ↑ Shahzad, Naiyer; Khan, Wajahatullah; Md, Shadab; Ali, Asgar; Saluja, Sundeep Singh; Sharma, Sadhana; Al-Allaf, Faisal A.; Abduljaleel, Zainularifeen et al. (1 April 2017). "Phytosterols as a natural anticancer agent: Current status and future perspective" (in en). Biomedicine & Pharmacotherapy 88: 786–794. doi:10.1016/j.biopha.2017.01.068. https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0753332216324052.

- ↑ Udoh, Michael; Santiago, Marina; Devenish, Steven; McGregor, Iain S.; Connor, Mark (1 December 2019). "Cannabichromene is a cannabinoid CB 2 receptor agonist" (in en). British Journal of Pharmacology 176 (23): 4537–4547. doi:10.1111/bph.14815. ISSN 0007-1188. PMC PMC6932936. PMID 31368508. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/bph.14815.

- ↑ Zurier, Robert B.; Burstein, Sumner H. (1 November 2016). "Cannabinoids, inflammation, and fibrosis" (in en). The FASEB Journal 30 (11): 3682–3689. doi:10.1096/fj.201600646R. ISSN 0892-6638. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1096/fj.201600646R.

- ↑ Broeckling, Corey D.; Ganna, Andrea; Layer, Mark; Brown, Kevin; Sutton, Ben; Ingelsson, Erik; Peers, Graham; Prenni, Jessica E. (20 September 2016). "Enabling Efficient and Confident Annotation of LC−MS Metabolomics Data through MS1 Spectrum and Time Prediction" (in en). Analytical Chemistry 88 (18): 9226–9234. doi:10.1021/acs.analchem.6b02479. ISSN 0003-2700. https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acs.analchem.6b02479.

- ↑ Chong, Jasmine; Wishart, David S.; Xia, Jianguo (1 December 2019). "Using MetaboAnalyst 4.0 for Comprehensive and Integrative Metabolomics Data Analysis" (in en). Current Protocols in Bioinformatics 68 (1). doi:10.1002/cpbi.86. ISSN 1934-3396. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/cpbi.86.

- ↑ Xiong, Wei; Cui, Tanxing; Cheng, Kejun; Yang, Fei; Chen, Shao-Rui; Willenbring, Dan; Guan, Yun; Pan, Hui-Lin et al. (4 June 2012). "Cannabinoids suppress inflammatory and neuropathic pain by targeting α3 glycine receptors" (in en). Journal of Experimental Medicine 209 (6): 1121–1134. doi:10.1084/jem.20120242. ISSN 1540-9538. PMC PMC3371734. PMID 22585736. https://rupress.org/jem/article/209/6/1121/41297/Cannabinoids-suppress-inflammatory-and-neuropathic.

- ↑ Johnson, Sarah A; Prenni, Jessica E; Heuberger, Adam L; Isweiri, Hanan; Chaparro, Jacqueline M; Newman, Steven E; Uchanski, Mark E; Omerigic, Heather M et al. (20 February 2021). "Comprehensive Evaluation of Metabolites and Minerals in 6 Microgreen Species and the Influence of Maturity" (in en). Current Developments in Nutrition 5 (2): nzaa180. doi:10.1093/cdn/nzaa180. ISSN 2475-2991. PMC PMC7897203. PMID 33644632. https://academic.oup.com/cdn/article/doi/10.1093/cdn/nzaa180/6041711.

- ↑ Haugen, John-Erik; Tomic, Oliver; Kvaal, Knut (1 February 2000). "A calibration method for handling the temporal drift of solid state gas-sensors" (in en). Analytica Chimica Acta 407 (1-2): 23–39. doi:10.1016/S0003-2670(99)00784-9. https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0003267099007849.

- ↑ Adesina, Ifeoluwa; Bhowmik, Arnab; Sharma, Harmandeep; Shahbazi, Abolghasem (14 April 2020). "A Review on the Current State of Knowledge of Growing Conditions, Agronomic Soil Health Practices and Utilities of Hemp in the United States" (in en). Agriculture 10 (4): 129. doi:10.3390/agriculture10040129. ISSN 2077-0472. https://www.mdpi.com/2077-0472/10/4/129.

- ↑ Rampler, Evelyn; Abiead, Yasin El; Schoeny, Harald; Rusz, Mate; Hildebrand, Felina; Fitz, Veronika; Koellensperger, Gunda (12 January 2021). "Recurrent Topics in Mass Spectrometry-Based Metabolomics and Lipidomics—Standardization, Coverage, and Throughput" (in en). Analytical Chemistry 93 (1): 519–545. doi:10.1021/acs.analchem.0c04698. ISSN 0003-2700. PMC PMC7807424. PMID 33249827. https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acs.analchem.0c04698.

- ↑ Anthony, Brendon M.; Chaparro, Jacqueline M.; Prenni, Jessica E.; Minas, Ioannis S. (1 December 2020). "Early metabolic priming under differing carbon sufficiency conditions influences peach fruit quality development" (in en). Plant Physiology and Biochemistry 157: 416–431. doi:10.1016/j.plaphy.2020.11.004. https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0981942820305556.

- ↑ Yao, Linxing; Sheflin, Amy M.; Broeckling, Corey D.; Prenni, Jessica E. (2019), D'Alessandro, Angelo, ed., "Data Processing for GC-MS- and LC-MS-Based Untargeted Metabolomics" (in en), High-Throughput Metabolomics (New York, NY: Springer New York) 1978: 287–299, doi:10.1007/978-1-4939-9236-2_18, ISBN 978-1-4939-9235-5, http://link.springer.com/10.1007/978-1-4939-9236-2_18

- ↑ Smith, Colin A.; Want, Elizabeth J.; O'Maille, Grace; Abagyan, Ruben; Siuzdak, Gary (1 February 2006). "XCMS: Processing Mass Spectrometry Data for Metabolite Profiling Using Nonlinear Peak Alignment, Matching, and Identification" (in en). Analytical Chemistry 78 (3): 779–787. doi:10.1021/ac051437y. ISSN 0003-2700. https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/ac051437y.

- ↑ Broeckling, C. D.; Afsar, F. A.; Neumann, S.; Ben-Hur, A.; Prenni, J. E. (15 July 2014). "RAMClust: A Novel Feature Clustering Method Enables Spectral-Matching-Based Annotation for Metabolomics Data" (in en). Analytical Chemistry 86 (14): 6812–6817. doi:10.1021/ac501530d. ISSN 0003-2700. https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/ac501530d.

- ↑ Broeckling, Corey D.; Ganna, Andrea; Layer, Mark; Brown, Kevin; Sutton, Ben; Ingelsson, Erik; Peers, Graham; Prenni, Jessica E. (20 September 2016). "Enabling Efficient and Confident Annotation of LC−MS Metabolomics Data through MS1 Spectrum and Time Prediction" (in en). Analytical Chemistry 88 (18): 9226–9234. doi:10.1021/acs.analchem.6b02479. ISSN 0003-2700. https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acs.analchem.6b02479.

- ↑ Chong, Jasmine; Wishart, David S.; Xia, Jianguo (1 December 2019). "Using MetaboAnalyst 4.0 for Comprehensive and Integrative Metabolomics Data Analysis" (in en). Current Protocols in Bioinformatics 68 (1). doi:10.1002/cpbi.86. ISSN 1934-3396. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/cpbi.86.

Notes

This presentation is faithful to the original, with only a few minor changes to presentation. Some grammar and punctuation was cleaned up to improve readability. In some cases important information was missing from the references, and that information was added.