Journal:Enzyme immunoassay for measuring aflatoxin B1 in legal cannabis

| Full article title | Enzyme immunoassay for measuring aflatoxin B1 in legal cannabis |

|---|---|

| Journal | Toxins |

| Author(s) | Di Nardo, Fabio; Cavalera, Simone; Baggiani, Claudio; Ciarello, Matteo; Pazzi, Marco; Anfossi, Laura |

| Author affiliation(s) | University of Turin |

| Primary contact | Email: laura dot anfossi at unito dot it |

| Year published | 2020 |

| Volume and issue | 12(4) |

| Article # | 265 |

| DOI | 10.3390/toxins12040265 |

| ISSN | 2072-6651 |

| Distribution license | Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International |

| Website | https://www.mdpi.com/2072-6651/12/4/265/htm |

| Download | https://www.mdpi.com/2072-6651/12/4/265/pdf (PDF) |

|

|

This article should be considered a work in progress and incomplete. Consider this article incomplete until this notice is removed. |

Abstract

The diffusion of the legalization of cannabis for recreational, medicinal, and nutraceutical uses requires the development of adequate analytical methods to assure the safety and security of such products. In particular, aflatoxins are considered to pose a major risk for the health of cannabis consumers. Among analytical methods that allow for adequate monitoring of food safety, immunoassays play a major role thanks to their cost-effectiveness, high-throughput capacity, simplicity, and limited requirement for equipment and skilled operators. Therefore, a rapid and sensitive enzyme immunoassay has been adapted to measure the most hazardous aflatoxin B1 in cannabis products. The assay was acceptably accurate (recovery rate: 78–136%), reproducible (intra- and inter-assay means coefficients of variation 11.8% and 13.8%, respectively), and sensitive (limit of detection and range of quantification: 0.35 ng mL−1 and 0.4–2 ng mL−1, respectively corresponding to 7 ng g−1 and 8–40 ng g−1 in the plant), while providing results which agreed with a high-performance liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry (HPLC-MS/MS) method for the direct analysis of aflatoxin B1 in cannabis inflorescence and leaves. In addition, the carcinogenic aflatoxin B1 was detected in 50% of the cannabis products analyzed (14 samples collected from small retails) at levels exceeding those admitted by the European Union in commodities intended for direct human consumption, thus envisaging the need for effective surveillance of aflatoxin contamination in legal cannabis.

Keywords: mycotoxins, food safety, medicinal herbs, competitive immunoassay

Introduction

Cannabis sativa is a plant of the Cannabaceae family and is well-known for its content of biologically active chemical compounds, among which are the major compounds Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol (Δ9-THC) and cannabidiol (CBD). The flowering or fruiting tops of the Cannabis plant have been controlled in the United States under the Controlled Substances Act since 1970 under the drug class “Marihuana.”[1]

Cannabis products can be used for medicinal purposes (whether using the psychoactive constituent THC or the non-psychoactive constituent CBD, generally referred to as "medical cannabis"), in manufacturing ("industrial hemp"), and for non-medical intoxication ("recreational or psychoactive cannabis").[2] The number of active constituents found in cannabis and the variety of their effects have also suggested cannabis' potential use as a dietary supplement and nutraceutical.[1][3] According to the World Health Organization (WHO), recreational cannabis is the most widely used illicit drug and the most largely cultivated and trafficked worldwide.[4]

The therapeutic application of cannabis is increasing around the world.[5] For example, a medicine based on cannabis extract has been approved by the European Medicines Agency.[6] THC can be medically administered as capsules, mouth spray, or as flowers for making tea. And the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has approved one cannabis-derived and three cannabis-related drug products.[7]

The cultivation and supply of cannabis for industrial use has been legal in the European Union since 2013, provided the cannabis' THC content does not exceed 0.2%.[8] In 2018, the U.S. legalized the production and marketing of hemp, provided that its THC content is below 0.3% on a dry weight basis.[1]

As cannabis increasingly becomes legalized for recreational purposes, dietary supplements, and various medical applications, growth of the global legal market of such products looks favorable in the coming years. However, the toxicity of common cannabis contaminants to humans is largely unknown. Due to the ambiguity between legal and illicit production and supply of cannabis products, there is a significant lacking in the literature regarding the prevalence of cannabis contaminants and of their harmfulness to humans. Contemporarily, the expanded use of cannabis products demands further research in this area, especially for therapeutic uses.[9]

Several classes of contaminants can be present in cannabis, including heavy metals, which are able to bioaccumulate in Cannabis plants[10]; pesticides, (including illegal pesticides; given how long cannabis has been illegal, pesticide guidelines or maximal limits for pesticide residues have not been set for this substrate); microbiological contaminants; and toxins from microbial overloads, such as ochratoxins and aflatoxins.[11][12]

McKernan et al. showed that toxigenic fungi grow on cannabis (especially those producing ochratoxin and aflatoxin) and highlighted the need to investigate the presence of the corresponding mycotoxins in these kinds of samples.[13] Among mycotoxins that can affect cannabis, aflatoxins (AFs) are of utmost concern because of their toxicity and their widespread distribution. AFs are carcinogens, genotoxic, and immunosuppressive agents.[14] In particular, aflatoxin B1 (AFB1) is the most recurrent and carcinogenic of the aflatoxins, and it is well documented to be a causative agent of hepatocellular carcinoma as well as growth suppression, immune system modulation, and malnutrition.[15][16] AFB1 is produced by fungi of the Aspergillus genus, namely Aspergillus flavus and Aspergillus parasiticus.

A. flavus is ubiquitously found in soil and contaminates a wide range of the world’s crops. After establishing the plant as a host, the fungus produces aflatoxins, including AFB1. Fungal growth can occur on crops at any point in the pre- or post-harvest stage. Additionally, high temperatures and humidity favor fungal growth, so carelessness of storage conditions favors a large amount of AFB1 contamination occurring during storage.[17]

The lack of regulations and the prevailing illegal production, storage, and consumption of cannabis have meant a general unavailability of controls on its safety, including the absence of methods to monitor contamination. In this work, a rapid and sensitive enzyme immunoassay for measuring AFB1—primarily developed to monitor the presence of the toxin in eggs[18]—was adapted for detecting AFB1 in cannabis products. Although several accurate and sensitive immunoenzymatic kits for AFB1 detection are available on the market, the indiscriminate use of immunoassay kits originally developed and validated for application in specific matrices (to monitor AFB1 in very different materials) should be carefully evaluated. Therefore, samples of cannabis derivatives (inflorescence and leaves) legally sold under the requirement of THC content lower than 0.2% were collected in small retail outlets in Torino (Italy). The enzyme immunoassay was modified in order to comply with the effect of the herbaceous matrix and the modified assay was in-house validated. A chromatographic tandem mass spectrometry method was also developed to confirm accuracy of the enzyme immunoassay. Finally, the sensitive enzyme immunoassay was used to measure AFB1 contamination in 14 samples of cannabis products.

Results

Enzyme immunoassay adaptation to AFB1 detection in cannabis products

Extraction of aflatoxin B1 from cannabis leaves and seeds was carried out by partitioning in 80% methanol, as previously reported by other researchers for AFB1 extraction from several kinds of medical plants.[19][20]

The enzyme immunoassay used in this work was initially developed for measuring aflatoxins in eggs[18] and consisted of a direct competitive immunoassay, in which a polyclonal antibody raised against aflatoxin M1 linked to bovine serum albumin (BSA) (antiM1-pAb) was adsorbed onto the polystyrene of microplate wells. The target compound (AFB1) and the enzyme probe (AFB1 linked to horse radish peroxidase, AFB1-HRP) competed for binding to the anchored antibody. After removing unbound fractions by washing the plate, the signal generated by the enzyme was developed and measured. The time required to complete the analysis was 30 minutes. In previous work, we also produced a second polyclonal antibody using AFB1 linked to BSA as the immunogen (antiB1-pAb). The antiB1-pAb showed higher selectivity towards AFB1 compared to the antiM1-pAb and was used in this work. Therefore, optimal AFB1-HRP and antiB1-pAb concentrations were defined ex-novo through the checkerboard titration approach. Other assay parameters were also re-evaluated. In particular, AFB1-HRP and antiB1-pAb concentrations and time of reactions were decided upon, providing a signal of the blank of approximately 1.5 UA and an IC50 of the calibration curve below 1 ng mL−1. Other parameters were defined based on minimizing matrix effect. Hence, extracts were fortified with known concentrations of AFB1 and the relative matrix effect (ME%) was calculated as follows:

ME% = (AFB1 measured in the fortified extract − AFB1 measured in the non-fortified extract) / AFB1 added × 100[21]

As the scope of the re-optimization of the enzyme immunoassay was intended for coping with new interference in AFB1 quantification due to the specific composition of the cannabis matrix, recovery was measured by fortifying the extract, which included potential interfering substances deriving from the sample.

A modification of the pristine protocol was considered for statistically significant improvement of the obtained ME% rate.

Two samples (representative of leaves and inflorescence) collected in a small local retail outlet were extracted and, using the methanolic extracts fortified with AFB1, the following parameters were studied: (1) dilution of the methanolic extract with water; (2) volume of the diluted extract to be added to the reaction well; (3) time for the immuno- and enzymatic reactions; (4) nature of the buffer for AFB1-HRP dilution; and (5) composition of the washing solution.

In particular, we observed that a precipitate formed when the methanolic extracts were diluted with water; however, filtration and centrifugation to remove the particulate matter caused a dramatic loss of the toxin, measured by recovery values below 50%. Then, the raw suspension was diluted 1 + 1 and added directly to the wells. Higher dilution rate (1 + 3) decreased the sensitivity of the assay (because of sample dilution) without increasing recovery rates, while using the undiluted extract produced a strong matrix effect evidenced by a large overestimation of the AFB1. For avoiding excessive matrix interference, the sample volume was reduced to one half (further reducing sample volume was ineffective for increasing recovery and halved the sensitivity). The pH of the buffer used for the immunoreaction and of the washing solutions was also modified in order to obtain satisfying recovery rates. Specifically, lowering the pH of both solutions to 5.0 allowed us to suppress most of the matrix interference. On the contrary, modification of composition (salts and additives) of buffers did not allow us to significantly improve recovery rates (see Supplementary materials, Figure S1). Finally, the time of reactions was defined to limit the overall time required for completing the analysis while providing a signal of the blank that was measured with acceptable precision (>1 UA). The total time for the analysis was 40 minutes, which is quite low for microplate-based immunoassays and acceptable for the intended use as a first-level screening analysis.

The experimental conditions considered in the study and the protocol optimized for AFB1 detection in cannabis are shown in Table 1. Several parameters of the pristine protocol needed to be modified to achieve acceptable recovery rates in the detection of AFB1 in cannabis products instead of in egg yolk. This finding pointed out that the use of commercial kits originally intended for specific applications to different commodities without modifications can lead to inaccuracy and should be discouraged.

| |||||||||||||||||||||

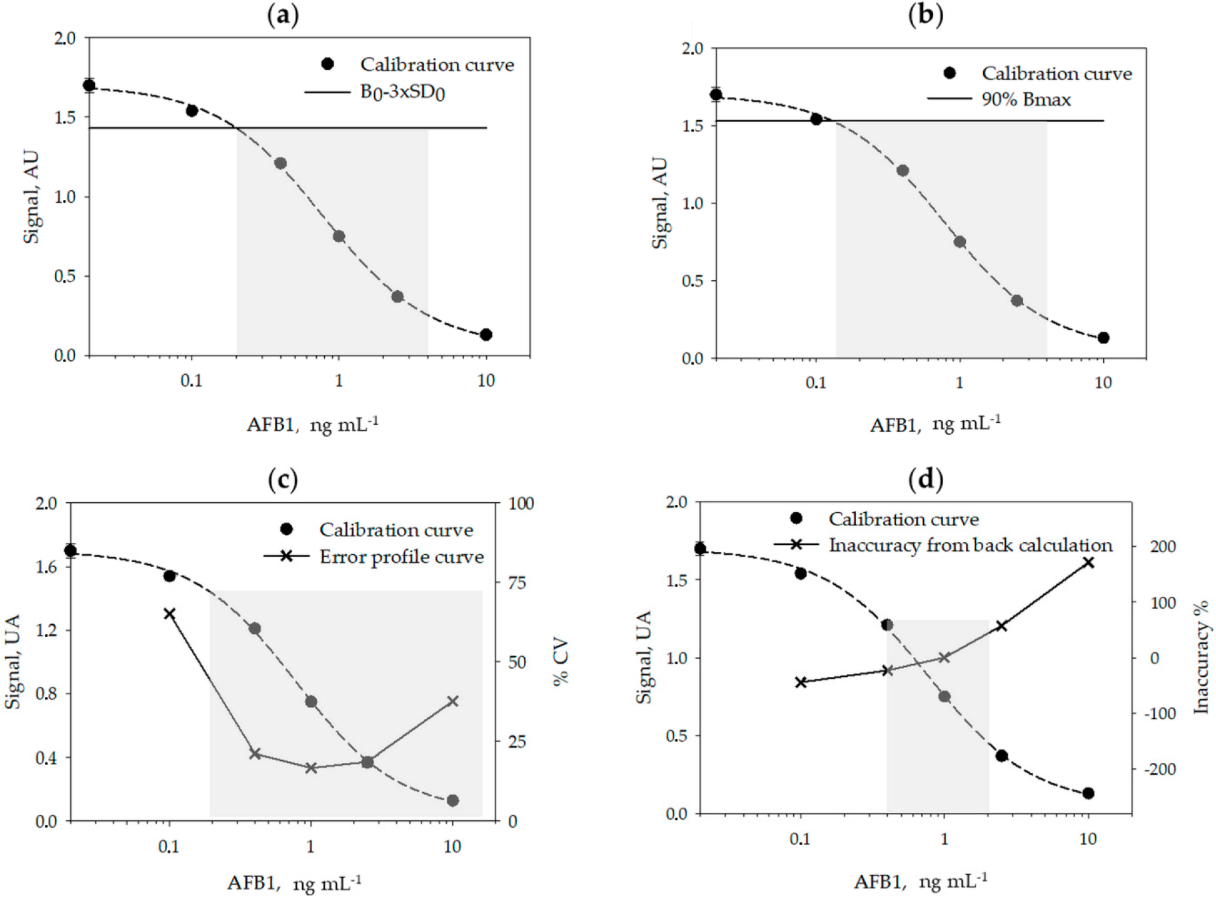

A typical calibration curve for measuring AFB1 obtained in the optimized conditions is shown in Figure 1.

|

Analytical figures of merits of the enzyme immunoassay

Using six calibration curves, generated on different days, and by using six calibrators measured in duplicate on each day, we studied the reproducibility of the calibration (Table 2) and calculated the limit of detection (LOD) and the range of quantification (ROQ) of the assay (Table 3 and Figure 1, above). Signals recorded on each day were normalized by the signal of the calibrator containing no AFB1 (B0). The LOQ and ROQ were estimated according to four methods, variously applied to competitive immunoassays: the signal-to-noise method[21][22], the IC10/20–80 method[23][24][25][26], the error profile method[27], and the back-calculation method.[28]

| ||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The calibration parameters were acceptably repeatable within different analytical sessions and days. The limit of detection varied depending on the method used for its estimation between 0.12 ng mL−1 (Bmax inhibition) and 0.35 ng mL−1 (back-calculation method). The quantification range also varied depending upon the method used to calculate it. Especially, the back-calculation method gave the narrower interval (0.4–2 ng mL−1) while according to the error profile method, the quantification range spanned from 0.2 to 14 ng mL−1 (Figure 1). The LOD varied among methods by a factor of three and the ROQ approximately by one order of magnitude. Whatever the method, the enzyme immunoassay showed high sensitivity.

Selectivity towards other mycotoxins was measured by calculating the cross-reactivity (CR), defined as follows: CR% = IC50 AFB1/IC50 mycotoxin × 100 (see Supplementary materials, Table S1). The selectivity trend was similar to the one observed previously for the same antibody.[15] In details, other compounds in the class of aflatoxins showed a certain degree of cross-reactivity, which ranged from 2.0% (AFM1) to 25.3% (AFG1). Other mycotoxins with unrelated structures (i.e., ochratoxin A, zearalenone, and fumonisins) did not interfere at all.

Measuring AFB1 in cannabis products by the enzyme immunoassay

The trueness of the assay was studied by recovery experiments. Two cannabis samples (#JA, made of leaves, and #DI comprising inflorescence) were analyzed directly and after fortification of the raw sample (10 and 20 ng/g of AFB1). Apparently, sample #DI contained AFB1 (9.6 ng g−1), while sample #JA showed an apparent AFB1 content of 2.8 ng g−1(corresponding to 0.28 ng mL−1 in the extract). This value was below the LOD estimated by the back-calculation method, while exceeding those calculated by the other methods. Sample #JA was then diluted 1 + 1, 1 + 3, and 1 + 7 with the extraction solvent and analyzed again. We expected that sample dilution would produce a proportional signal increase. On the contrary, signals were randomly scattered. We conclude that AFB1 content of sample #JA was below the detection limit of the assay; therefore, we assumed the LOD calculated by the back-calculation method as the most reliable for determining AFB1 in cannabis samples. According to the assignment of sample #JA as containing undetectable amounts of AFB1, satisfactory recovery rates (83–113%; see Supplementary materials, Table S2) were obtained for both samples.

The reproducibility of the enzyme assay was evaluated by measuring one sample in six replicates within the same day (intra-assay repeatability) and five samples in duplicates on two different days (inter-assay variability). The intra-assay relative standard deviation (RSD %) and the mean of inter-assay RSD% were 11.8% and 13.8%, respectively.

Determination of AFB1 in cannabis products using high-performance liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry (HPLC–MS/MS)

To validate the enzyme immunoassay, an HPLC-MS/MS method for measuring AFB1 in cannabis products was developed in-house by adapting the method of Zheng et al., previously reported for the detection of major aflatoxins in medicinal herbs.[29] The method of Zheng et al. involved the analysis of the crude herbal extract without purification or pre-concentration and allowed the differentiation of various aflatoxins. The separation was obtained by a gradient elution in reverse phase liquid chromatography, and the detection was in the single reaction monitoring (SRM) mode. To comply with matrix interference, AFM1 was used as the internal standard, provided that AFM1 forms from the animal metabolism and then its presence in herbal extract could be excluded. The linearity of the calibration was confirmed between 5–40 ng mL−1 (y = 0.56x − 0.67, r2 = 0.992; see Supplementary materials, Figure S2) and the LOD and LOQ were calculated as 1.8 and 5.8 ng mL−1 (corresponding to 18 and 58 ng g−1 in the sample), respectively. The limit of detection of the HPLC-MS/MS method was five to ten times higher than the one calculated for the enzyme immunoassay (depending on the method used to calculate this last). The poor sensitivity compared to chromatography coupled to mass spectrometry[30] was due to the fact that we analyzed the crude extracts without applying any clean-up or pre-concentration and that we did not optimize the method. To evaluate matrix interference, four samples were analyzed by the HPLC-MS/MS method. All samples contained AFB1 below the limit of detection of the method. The extracts from four samples (two extracts for each sample) were then fortified with 10 ng mL−1 of AFB1. Relative matrix effect values for fortified samples ranged from 81 to 123%, with a certain variability also among duplicate samples (Table 4).

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Method comparison: Enzyme immunoassay and HPLC-MS/MS

To further confirm that the enzyme immunoassay was not affected by the interference of the matrix and by its intrinsic variability (leaf, flowers, seeds and other parts of the cannabis plant were occasionally present in the samples collected in small retail outlets), four samples were divided into sub-samples (two sub-samples were generated for each sample) and extracted and analyzed on different days. As observed for the HPLC-MS/MS validation, again certain variability between sub-samples was observed (Table 4, above).

In parallel, a further total of 10 samples was extracted and analyzed directly after fortifying the extracts with 10 ng mL-1 of AFB1 by the in-house-developed HPLC-MS/MS method and by the enzyme immunoassay (fortified extracts were analyzed by the enzyme immunoassay after a 1:10 dilution in the extraction solvent to comply with the ROQ). The results showed all samples contained AFB1 below the limit of detection of the HPLC-MS/MS method, while according to the enzyme immunoassay 50% of samples were contaminated above the LOD. The mean AFB1 content was measured to be 12.3 ng g-1 and the contamination level varied between 8.6 and 17.7 ng g-1 (Table 4, above).

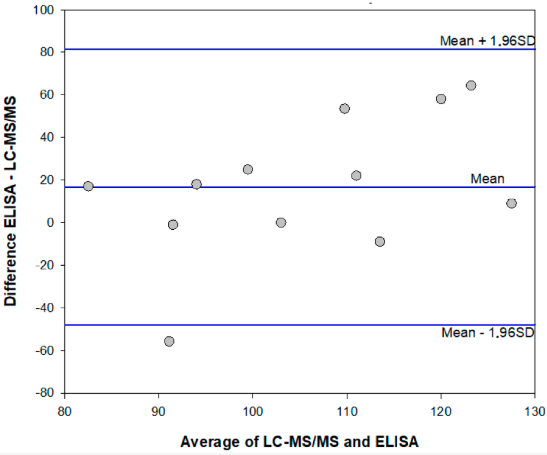

The mean ME% calculated for fortified extracts were 108% (78–136%) and 99% (74–123%) for the enzyme immunoassay and the HPLC-MS/MS method, respectively. Results which agreed were obtained in the two analytical methods, although the enzyme immunoassay showed a tendency to overestimate AFB1 contamination in comparison to the HPLC-MS/MS method. (Figure 2 and Table 4, above).

|

Discussion

A rapid, accurate, and sensitive enzyme immunoassay was established for the measurements of AFB1 in cannabis products, based on previously developed bioreagents. The re-evaluation of assay parameters and particularly of the pH of the buffers and the washing solution allowed us to adapt the assay to the novel matrix and to mitigate the influence of the large variability in the composition of extracts from different part of the cannabis plant. To comply with possible variability of the matrix, a prudential limit of detection was decided, which was calculated from the inaccuracy of repeated calibration curves[28] and validated by dilution and recovery experiments on two cannabis samples. Actually, the limit of detection (LOD) and the range of quantification (ROQ) are variously defined for immunological-based assays, in particular for competitive immunoassays, where the signal is inversely (and not linearly) correlated to the concentration of the target. Sometimes, the signal-to-noise ratio method[21][22] is used to calculate the LOD, which is then assumed as the concentration of the analyte that corresponds to the signal of the standard 0 (B0) minus two or three standard deviation of the standard 0. However, this method has some limitations when applied to non-linear curve fitting. As an alternative, especially suitable for competitive immunoassays in which data are fitted by the four parameter logistic model (4-PL), a certain level of inhibition of the maximum binding (Bmax) is considered to estimate the LOD and ROQ.[23][24][25][26][31][32] The inhibition levels most frequently considered for the purpose are 90% for estimating the LOD, and 85%–15%[31][32] or 80–20%[23][24][25][26] for the ROQ, respectively. The rationale beyond this approach is represented by the fact that the typical standard curve of competitive immunoassays has a sigmoidal shape, and the upper and lower parts of the curve are strongly imprecise. However, the inhibition levels are, in some way, arbitrarily defined.

A more robust identification of significant inhibition levels is based on the use of the error profile curve (also called precision profile). In this method, the relative standard deviation (RSD %) of repeated experiments is calculated for various concentrations of the analyte (typically for calibrators) and plotted towards the calibrators’ concentrations. The ROQ and LOD are defined as the interval of concentrations that can be measured with a certain precision.[27][33] However, the level of acceptable imprecision is debated. Some authors have 30% and 10% for estimating the LOD and ROQ, respectively[29], while others considered 50% as the maximum acceptable imprecision.[31] In addition, modelling precision profile is complicated and discourages the application of this criterion. A concept similar to using the precision profile is the back-calculation method, in which the concentration of the calibrators is estimated by the fit of the curve and the interval of quantification is defined as the concentrations estimated with an acceptable accuracy (±20%).[28][33] The limit of detection is calculated as the lower concentration that provides inaccuracy below 25%.[28]

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 U.S. Food and Drug Administration. "FDA Regulation of Cannabis and Cannabis-Derived Products, Including Cannabidiol (CBD)". U.S. Food and Drug Administration. https://www.fda.gov/news-events/public-health-focus/fda-regulation-cannabis-and-cannabis-derived-products-including-cannabidiol-cbd. Retrieved 10 July 2019.

- ↑ Mead, A. (2019). "Legal and Regulatory Issues Governing Cannabis and Cannabis-Derived Products in the United States". Frontiers in Plant Science 10: 697. doi:10.3389/fpls.2019.00697. PMC PMC6590107. PMID 31263468. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6590107.

- ↑ Hartsel, J.A.; Eades, J.; Hickory, B.; Makriyannis, A. (2016). "Chapter 53: Cannabis sativa and Hemp". In Gupta, R.C.. Nutraceuticals: Efficacy, Safety and Toxicity. Academic Press. pp. 735–754. ISBN 9780128021477.

- ↑ World Health Organization. "Cannabis". Management of substance abuse. World Health Organization. https://www.who.int/substance_abuse/facts/cannabis/en/. Retrieved 20 April 2020.

- ↑ Bridgeman, M.B.; Abazia, D.T. (2017). "Medicinal Cannabis: History, Pharmacology, And Implications for the Acute Care Setting". P & T 42 (3): 180–88. PMC PMC5312634. PMID 28250701. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5312634.

- ↑ European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction (December 2018). "Medical use of cannabis and cannabinoids: Questions and answers for policymaking". EMCDDA. doi:0.2810/979004. https://www.emcdda.europa.eu/publications/rapid-communications/medical-use-of-cannabis-and-cannabinoids-questions-and-answers-for-policymaking_en. Retrieved 04 November 2019.

- ↑ Corroon, J.; Kight, R. (2018). "Regulatory Status of Cannabidiol in the United States: A Perspective". Cannabis and Cannabinoid Research 3 (1): 190-194. doi:10.1089/can.2018.0030. PMC PMC6154432. PMID 30283822. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6154432.

- ↑ "Regulation (EU) No 1307/2013 of the European Parliament and of the Council". Official Journal of the European Union. 20 December 2013. pp. 608–70. https://eur-lex.europa.eu/LexUriServ/LexUriServ.do?uri=OJ:L:2013:347:0608:0670:EN:PDF.

- ↑ Dryburgh, L.M.; Bolan, N.S.; Grof, C.P.L. et al. (2018). "Cannabis Contaminants: Sources, Distribution, Human Toxicity and Pharmacologic Effects". British Journal of Clinical Pharmacology 84 (11): 2468-2476. doi:10.1111/bcp.13695. PMC PMC6177718. PMID 29953631. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6177718.

- ↑ Zerihun, A. Chandravanshi, B.S.; Debebe, A. et al. (2015). "Levels of Selected Metals in Leaves of Cannabis Sativa L. Cultivated in Ethiopia". SpringerPlus 4: 359. doi:10.1186/s40064-015-1145-x. PMC PMC4503701. PMID 26191486. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4503701.

- ↑ Llewellyn, G.C.; O'Rear, C.E. (1977). "Examination of Fungal Growth and Aflatoxin Production on Marihuana". Mycopathologia 62 (2): 109–12. doi:10.1007/BF01259400. PMID 414138.

- ↑ Wilcox, J.; Pazdanska, M.; Milligan, C. (2020). "Analysis of Aflatoxins and Ochratoxin A in Cannabis and Cannabis Products by LC-Fluorescence Detection Using Cleanup With Either Multiantibody Immunoaffinity Columns or an Automated System With In-Line Reusable Immunoaffinity Cartridges". Journal of AOAC International 103 (2): 494–503. doi:10.5740/jaoacint.19-0176. PMID 31558181.

- ↑ McKernan, K.; Spangler, J.; Zhang, L. et al. (2015). "Cannabis Microbiome Sequencing Reveals Several Mycotoxic Fungi Native to Dispensary Grade Cannabis Flowers". F1000Research 4: 1422. doi:10.12688/f1000research.7507.2. PMC PMC4897766. PMID 27303623. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4897766.

- ↑ European Food Safety Authority. "Aflatoxins in food". https://www.efsa.europa.eu/en/topics/topic/aflatoxins-food. Retrieved 10 July 2019.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 Marchese, S.; Polo, A.; Ariano, A. et al. (2018). "Aflatoxin B1 and M1: Biological Properties and Their Involvement in Cancer Development". Toxins 10 (6): 214. doi:10.3390/toxins10060214. PMC PMC6024316. PMID 29794965. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6024316.

- ↑ International Agency for Research on Cancer (2002). Some Traditional Herbal Medicines, Some Mycotoxins, Naphthalene and Styrene. IARC Monographs on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risks to Humans. 82. pp. 171–274. doi:10.3390/toxins10060214. PMC PMC6024316. PMID 29794965.

- ↑ Rushing, B.R.; Selim, M.I. (2019). "Aflatoxin B1: A Review on Metabolism, Toxicity, Occurrence in Food, Occupational Exposure, and Detoxification Methods". Food and Chemical Toxicology 124: 81–100. doi:10.1016/j.fct.2018.11.047. PMID 30468841.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 18.2 Anfossi, L.; Di Nardo, F.; Giovannoli, C. et al. (2015). "Enzyme immunoassay for monitoring aflatoxins in eggs". Food Control 57: 115–21. doi:10.1016/j.foodcont.2015.04.013.

- ↑ Ventura, M.; Gómez, A.; Anaya, I. et al. (2004). "Determination of Aflatoxins B1, G1, B2 and G2 in Medicinal Herbs by Liquid Chromatography-Tandem Mass Spectrometry". Journal of Chromatography A 1048 (1): 25–9. doi:10.1016/j.chroma.2004.07.033. PMID 15453415.

- ↑ Arranz, I.; Sizoo, E.; van Egmond, H. et al. (2006). "Determination of Aflatoxin B1 in Medical Herbs: Interlaboratory Study". Journal of AOAC International 89 (3): 595-605. doi:10.1093/jaoac/89.3.595. PMID 16792057.

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 21.2 21.3 21.4 21.5 Zhang, Z.; Dong, S.; Ge, D. et al. (2018). "An Ultrasensitive Competitive Immunosensor Using Silica Nanoparticles as an Enzyme Carrier for Simultaneous Impedimetric Detection of Tetrabromobisphenol A bis(2-hydroxyethyl) Ether and Tetrabromobisphenol A Mono(hydroxyethyl) Ether". Biosensors and Bioelectronics 105: 77–80. doi:10.1016/j.bios.2018.01.029. PMID 29355782.

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 22.2 22.3 22.4 Reimer, G.J.; Gee, S.J.; Hammock, B.D. (1998). "Comparison of a Time-Resolved Fluorescence Immunoassay and an Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay for the Analysis of Atrazine in Water". Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry 46 (8): 3353–58. doi:10.1021/jf970965a.

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 23.2 23.3 23.4 23.5 Sasaki, D.; Mitchell, R.A. (2001). "How to Obtain Reproducible Quantitative ELISA Results" (PDF). Oxford Biomedical Research, Inc. https://www.oxfordbiomed.com/sites/default/files/2017-02/How%20to%20Obtain%20Reproducible%20Quantitative%20ELISA%20results.pdf.

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 24.2 24.3 24.4 24.5 Saeed, A.F.U.H.; Ling, S.; Yuan, J. et al. (2017). "The Preparation and Identification of a Monoclonal Antibody Against Domoic Acid and Establishment of Detection by Indirect Competitive ELISA". Toxins 9 (8): 250. doi:10.3390/toxins9080250. PMC PMC5577584. PMID 28817087. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5577584.

- ↑ 25.0 25.1 25.2 25.3 25.4 25.5 Zhang, X.; Yu, X.; Wen, K. et al. (2017). "Multiplex Lateral Flow Immunoassays Based on Amorphous Carbon Nanoparticles for Detecting Three Fusarium Mycotoxins in Maize". Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry 65 (36): 8063-8071. doi:10.1021/acs.jafc.7b02827. PMID 28825819.

- ↑ 26.0 26.1 26.2 26.3 26.4 26.5 Zhang, Z.; Zhu, N.; Zou, Y. et al. (2018). "A Novel and Sensitive Chemiluminescence Immunoassay Based on AuNCs@pepsin@luminol for Simultaneous Detection of Tetrabromobisphenol A bis(2-hydroxyethyl) Ether and Tetrabromobisphenol A Mono(hydroxyethyl) Ether". Analytica Chimica Acta 1035: 168-174. doi:10.1016/j.aca.2018.06.039. PMID 30224136.

- ↑ 27.0 27.1 27.2 27.3 27.4 Quinn, C.P.; Semenova, V.A.; Elie, C.M. et al. (2002). "Specific, Sensitive, and Quantitative Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay for Human Immunoglobulin G Antibodies to Anthrax Toxin Protective Antigen". Emerging Infectious Diseases 8 (10): 1103-10. doi:10.3201/eid0810.020380. PMC PMC2730307. PMID 12396924. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2730307.

- ↑ 28.0 28.1 28.2 28.3 28.4 28.5 28.6 Dunn, J.; Wild, D. (2013). "Calibration Curve Fitting". In Wild, D.. The Immunoassay Handbook (3rd ed.). Elsevier Science. pp. 323–336. ISBN 9780080445267.

- ↑ 29.0 29.1 Zheng, R.; Xu, H.; Wang, W. et al. (2014). "Simultaneous Determination of Aflatoxin B(1), B(2), G(1), G(2), Ochratoxin A, and Sterigmatocystin in Traditional Chinese Medicines by LC-MS-MS". Analytical and Bioanalytical Chemistry 406 (13): 3031-9. doi:10.1007/s00216-014-7750-7. PMID 24658469.

- ↑ Narváez, A.; Rodríguez-Carrasco, Y.; Castaldo, L. et al. (2020). "Ultra-High-Performance Liquid Chromatography Coupled With Quadrupole Orbitrap High-Resolution Mass Spectrometry for Multi-Residue Analysis of Mycotoxins and Pesticides in Botanical Nutraceuticals". Toxins 12 (2): 114. doi:10.3390/toxins12020114. PMC PMC7076805. PMID 32059484. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7076805.

- ↑ 31.0 31.1 31.2 Peckham, G.D.; Hew, B.E.; Waller, D.F. et al. (2013). "Amperometric Detection of Bacillus anthracis Spores: A Portable, Low-Cost Approach to the ELISA". International Journal of Electrochemistry 2013: 803485. doi:10.1155/2013/803485.

- ↑ 32.0 32.1 Zhang, C.; Zhang, Q.; Tang, X. et al. (2019). "Development of an Anti-Idiotypic VHH Antibody and Toxin-Free Enzyme Immunoassay for Ochratoxin A in Cereals". Toxins 11 (5): 280. doi:10.3390/toxins11050280. PMC PMC6563187. PMID 31137467. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6563187.

- ↑ 33.0 33.1 Food and Drug Administration (June 2019). "M10 Bioanalytical Method Validation". FDA-2019-D-1469. Food and Drug Administration. https://www.fda.gov/regulatory-information/search-fda-guidance-documents/m10-bioanalytical-method-validation. Retrieved 01 November 2019.

Notes

This presentation is faithful to the original, with only a few minor changes to presentation. Some grammar and punctuation was cleaned up to improve readability. In some cases important information was missing from the references, and that information was added. In the original article, citations 1 and 4 are duplicates; that duplication was removed for this version. The original's citation 34 is unclear, as they neither use the correct document name nor include a direct link to the document; an assumption is made that they intended to reference this FDA draft guidance.