User:Shawndouglas/sandbox/sublevel24

1. What is a cybersecurity plan and why do you need it?

Developing a cybersecurity plan is not a simple process; it requires expertise, resources, and diligence. Even a simple plan may involve several months of development, more depending on the complexity involved. The time it takes to develop the plan may also be impacted by how much executive support is provided, the size of the development team (bigger is not always better), and how available required resources are.[1]

Keep in mind that while this guide has been written with intent to broadly cover multiple industries, it does have a slight lean towards laboratories, particularly those implementing information systems.

2. What are the major standard and regulations dictating cybersecurity action?

3. The NIST Cybersecurity Framework and its control families

4. Fitting a framework or specification into a cybersecurity plan

5. Develop and create the cybersecurity plan

What follows is a template to help guide you in developing your own cybersecurity plan. Remember that this is a template and strategy for developing the cybersecurity plan for your organization, not a regulatory guidance document. This template has at its core a modified version of the template structure suggested in the late 2018 Cybersecurity Strategy Development Guide created for the National Association of Regulatory Utility Commissioners (NARUC).[1] While their document focuses on cybersecurity for utility cooperatives and commissions, much of what NARUC suggests can still be more broadly applied to all but the tiniest of businesses. Additional resources such as AHIMA's AHIMA Guidelines: The Cybersecurity Plan[4]; National Rural Electric Cooperative Association (NRECA), Cooperative Research Network's Guide to Developing a Cyber Security and Risk Mitigation Plan[2]; and various cybersecurity experts' articles[3][5][8][9][6][7] have been reviewed to further supplement the template. This template covers 10 main cybersecurity planning steps, each with multiple sub-steps. Additional commentary, guidance, and citation is included with those sub-steps.

Note that before development begins, you'll want to consider the knowledge resources available and key stakeholders involved. Do you have the expertise available in-house to address all 10 planning steps, or will you need to acquire help from one or more third parties? Who are the key individuals providing critical support to the business and its operations? Having the critical expertise and stakeholders involved with the plan's development process early on can enhance the overall plan and provide for more effective strategic outcomes.[1]

Also remind yourself that completing this plan will likely not require a straightforward, by-the-numbers approach. The most feasible outcome will have you jumping around a few steps and filling in blanks or revising statements in previous portions of the plan. While the ordering of these items is deliberate, completing them step by step may not make the best sense for your organization. Don't be afraid to go back and update sections you've worked on previously using new-found knowledge.

5.1. Develop strategic cybersecurity goals and define success

5.1.1 Broadly articulate business goals and how information technology relates

Something should drive you to want to implement a cybersecurity plan. Sometimes the impetus may be external, such as a major breach at another company that affects millions of people. But more often than not, well-formulated business goals and the resources, regulations, and motivations tied to them will propel development of the plan. Business goals have, hopefully, already been developed by the time you consider a cybersecurity plan. Now is the time to identify the technology and data that are tied to those goals. A clinical testing laboratory, for example, may have as a business goal "to provide prompt, accurate analysis of specimens submitted to the laboratory." Does the lab utilize information management systems as a means to better meet that goal? How secure are the systems? What are the consequences of having mission-critical data compromised in said systems?

5.1.2 Articulate why cybersecurity is vital to achieving those goals

Looking to your business goals for the technology, data, and other resources used to achieve those goals gives you an opportunity to turn the magnifying glass towards why the technology, data, and resources need to be secure. For example, the clinical testing lab will likely be dealing with protected health information (PHI), and an electric cooperative must reliably provide service practically 100 percent of the time. Both the data and the service must be protected from physical and cyber intrusion, at risk of significant and costly consequence. Be clear about what the potential consequences actually may be, as well as how business goals could be hindered without proper cybersecurity for critical assets. Or, conversely, clearly state what will be positively achieved by addressing cybersecurity for those assets.

5.1.3 State the cybersecurity mission and define how to achieve it, based on the above

You've stated your business goals, how technology and data plays a role in them, and why it's vital to ensure their security. Now it's time to develop your strategic mission in regards to cybersecurity. You may wish to take a few extra steps before defining the goals of that mission, however. The NARUC has this to say in that regard[1]:

Establishing a strategic [mission] is a critical first step that sets the tone for the entire process of drafting the strategy. Before developing [the mission], a commission may want to do an internal inventory of key stakeholders; conduct blue-sky thinking exercises; and do an environmental assessment and literature review to identify near-, mid-, and long-term drivers of change that may affect its goals.

Whatever cybersecurity mission goals you inevitably declare, you'll want to be sure they "provide a sense of purpose, identity, and long-term direction" and clearly communicate what's most important in regards to cybersecurity to internal and external customers. Also consider adding concise points that paint the overall mission as one dedicated to limiting vulnerabilities and keeping risks mitigated.[1]

5.1.4 Gain and promote active and visible support from executive management in achieving the cybersecurity mission

Ensuring executive management is fully on-board with your stated cybersecurity mission is vital. If key business leaders have not been intimately involved with the process as of yet, it is now time to gain their input and full support. As NARUC notes, "with leadership buy-in, it will be easier to institutionalize the idea that cybersecurity is a priority and can result in more readily available resources."[1] Consider what AHIMA calls a "State of the Union" approach to presenting the cybersecurity mission goals to leadership, being prepared to answer questions from them about responsible parties, communication policies, and "cyber insurance."[4] (Answers to such questions are addressed further into this template. You may wish to have some of what follows informally addressed before taking it to leadership. Or perhaps have an agreement to keep leadership appraised throughout cybersecurity plan development, gaining their feedback and overall acceptance of the plan as development comes to a close.)

5.2 Define scope and responsibilities

5.2.1 Define the scope and applicability through key requirements and boundaries

Now that the cybersecurity mission goals are clear and supported by leadership, it's time to tailor strategies based on those stated goals.

How broad of scope will the mission goals take you across your business assets? Information technology (IT) and data will surely be at the forefront, but don't forget to also address operational technology (OT) assets as well.[1] One helpful tool in determining the strategies and requirements needed to meet mission goals is to clearly define the logical and physical boundaries of your information system.[1][2] When considering those boundaries, remember the following[2]:

- An information system is more than a piece of software; it's a collection of all the components and other resources within the system's environment. Some of those will be internal and some external.

- The system is more than just hardware; the interfaces—physical and logical—as well as communication protocols also make up the system.

- The system has physical, logical, and security control boundaries, as well as data flows tied to those boundaries.

- The data housed and transmitted in the system is likely composed of varying degrees of sensitivity, further shaping boundaries.

- The information system's primary functions are directly tied to the goals of the business.

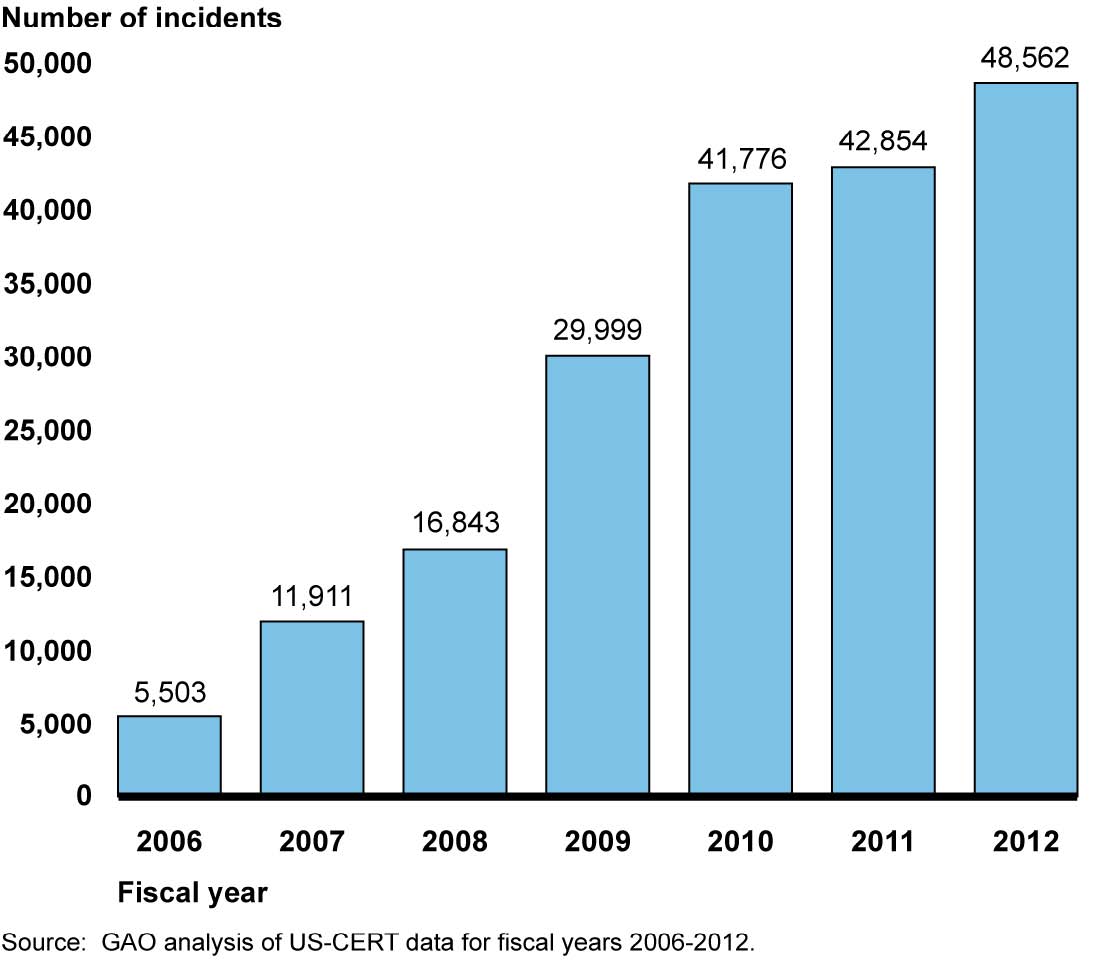

Additionally, when considering the scope of the plan, you'll also want to take into account advancements in both technology and cyber threats. "Unprecedented cybersecurity challenges loom just beyond the horizon," states CNA, a nonprofit research and analysis organization located in Arlington, Virginia. But we have to focus on more than just the "now." CNA adds that "today's operational security agenda is too narrow in scope to address the wide range of issues likely to emerge in the coming years."[10] Just as CNA is preparing a global initiative to shape policy on future cybersecurity challenges, so should you apply some focus to what potential technology upgrades may be made and what new cyber threats may appear.

Finally, some of the plan's scope may be dictated by prioritized assessment of risks to critical assets—addressed in the next section—and other assessments. It's important to keep this in mind when developing the scope; it may be affected by other parts of the plan. As you develop further sections of the plan, you may need to update previous sections with what you've learned.

5.2.2 Define the roles, responsibilities, and chain of command of those enacting and updating the cybersecurity plan

You'll also want to define who will fill what roles, what responsibilities they will have, and who reports to who, as part of the scope of your plan. This will include not only who's responsible for developing the cybersecurity plan (which you'll have hopefully determined early on) but also implementing, enforcing, and updating it. Having a senior manager who's able to oversee these responsibilities, make decisions, and enforce requirements will improve the plan's chance of success. Having clearly defined security-related roles and responsibilities (including security risk management) at one or more organizational levels (depending on how big your organization is) will also improve success rates.[1][2][6][7]

5.2.3 Ensure that roles and responsibility for security (the “who” of it) are clear

Defining roles, responsibilities, and chain of command isn't enough. Effectively communicating these roles and responsibilities to everyone inside and outside the organization—including third parties such as contractors and cloud providers—is vital. This typically involves encouraging transparency of cybersecurity and responsibility goals of the organization, as well as addressing everyday communications and education of everyone affected by the cybersecurity plan.[1][2][6] However, through it all, keep in mind for future communications and training that ultimately security is everyone's responsibility, from employees to contractors, not just those enacting and updating the plan.

5.3 Identify cybersecurity requirements and objectives

5.3.1 Detail the existing system and classify its critical and non-critical cyber assets

AHIMA recommends you "create an information asset inventory as a base for risk analysis that defines where all data and information are stored across the entire organization."[4] Consider any applications and systems used within the periphery of your operations, including business intelligence software, mobile devices, and legacy systems. Remember that any networked application or system could potentially be compromised and turned into a vector of attack. Additionally, classify and gauge those assets' based on type, risk, and criticality. What are their essential functions? How can they be grouped? How do they communicate: internally, externally, or not at all?[2] As AHIMA notes, you'll be able to use this asset inventory, in combination with a variety of additional assessments described below, as a base for your risk assessment.

5.3.2 Define the contained data and classify its criticality

During the asset inventory, you'll also want to address classifying the type of data contained or transported by the cyber asset, which aids in decision making regarding the controls you'll need to adequately protect the assets.[2] Use a consistent set of nomenclature to define the data. For example, if you look at universities such as the University of Illinois and Carnagie Mellon University, they provide guidance on how to classify institutional data based on characteristics such as criticality, sensitivity, and risk. The University of Illinois has a defined set of standardized terms such as "high-risk," "sensitive," "internal" and "public,"[11] whereas Carnagie Mellon uses "restricted," "private," and "public."[12] You don't necessarily need to use anyone's classification system verbatim; however, do use a consistent set of terminology to define and classify data.[2] Consider also adding additional details about whether the data is in motion, in use, or at rest.[13]

If you have difficulties classifying the data, pose a series of data protection questions concerning the data's characteristics. One such baseline for questions could be the European Union's definition of what constitutes personal data. For example[2][14]:

- Does the data identify an individual directly?

- Does the data relate specifically to an identifiable person?

- Could the data—when processed, lost, or misused—have an impact on an individual?

5.3.3 Identify current and previous cybersecurity policy and tools, as well as their effectiveness

Unless your business is in the formative stages, some type of technology infrastructure and policy likely exists. What, if any, cybersecurity policies and tools have you implemented in the past? Review any current access control protocols (e.g., role-based and "least privilege" policies) and security policies. Have they been updated to take into consideration recent changes in threats, risks, criticality, technology, or regulation?[4][3][6] In the same way, identify any past security policies and why they were discontinued. It may be convenient to track all these security protocols and policies in a master sheet, rather than spread out across multiple documents. Also, now might be a good time to identify how security-aware personnel are overall.[3] Of course, if protocols and policies aren't in place, create them, remembering to include proper communication, scheduled policy reviews, and training into the equation.

5.3.4 Identify the regulations, standards, and best practices affecting your assets and data

Arguably, most business types will be impacted by regulations, standards, or best practices. Even niche professions like cinema editors are guided by best practices set forth by professional organizations.[15] In the case of laboratories, multiple regulations and standards apply to operations, including information management and privacy practices. Presumably one or more executives in your business are familiar with the legal and professional aspects of how the business should be run. If not, significant research and outside consultant help may be required. Regardless, when approaching this task, ensure everyone understands the distinctions among "regulation," "standard," and "best practice."

Remember that while regulators may dictate how you manage your cybersecurity assets, setting policy that goes above and beyond regulation is occasionally detrimental to your business. Data retention requirements, for example, are important to consider, not only for regulatory purposes but also data management and security reasons. To be sure, numerous U.S. Code of Federal Regulations (e.g., 21 CFR Part 11, 40 CFR Part 141, and 45 CFR Part 164), European Union regulations (e.g., E.U. Annex 11 and E.U. Commission Directive 2003/94/EC), and even global entities (e.g., WHO Technical Report Series, #986, Annex 2) address the need for record retention. However, as AHIMA points out, records shouldn't be kept forever[4]:

Healthcare organizations have been storing and maintaining records and information well beyond record retention requirements. This creates significant additional security risks as systems and records must be maintained, patched, backed up, and provisioned (access) for longer than necessary or required by law ... In the era of big data the idea of keeping “everything forever” must end. It simply is not feasible, practical, or economical to secure legacy and older systems forever.

This example illustrates the idea that while regulatory compliance is imperative, going well beyond compliance limits has its own costs, not only financially but also by increasing cybersecurity risk.

5.3.5 Identify and analyze logical and physical system entry points and configurations

This step is actually closely tied to the next step concerning gap analysis. As such, you may wish to address both steps together. You've already identified your critical and non-critical assets, and performing a gap analysis on them may be a useful start in finding and analyzing the logical entry points of a system. But what are some of the most common entry points that attackers may use?[16][17][18][19]

- Inbound network-based attacks through software, network gateways, and online repositories

- Inbound network-based attacks through misconfigured firewalls and gateways

- Access to systems using stolen credentials (networked and physical)

- Access to peripheral systems via communication protocols, insecure credentials, etc. through lateral movement in the network

From email and enterprise resource planning (ERP) applications and servers to networking devices and tools, a wide variety of vectors for attack exist in the system, some more common than others. Analyzing these components and configurations takes significant expertise. If internal expertise is unavailable for this, it may require a third-party security assessment to gain a clearer picture of the entry points into your system. Even employees and their lack of cybersecurity knowledge may represent points of entry, via phishing schemes.[4][19] This is where training and internal random testing (addressed later) come into play.[4]

Physical access to system components and data also represent a significant attack vector, more so in particular industries and network set-ups. For example, industrial control systems in manufacturing plants may require extra consideration, with some control system vendors now offering an added layer of physical security in the form of physical locks that prevent code from being executed on the controller.[17] Cloud-based data centers and field-based monitoring systems represent other specialist situations requiring added physical controls.[2][4][6] That's not to say that even small businesses shouldn't worry about physical security; their workstations, laptops, USB drives, mobile devices, etc. can be compromised if made easy for the general public to access offices and other work spaces.[6] In regulated environments, physical access controls and facility monitoring may even be mandated.

5.3.6 Perform a gap analysis

A gap analysis is different from a risk analysis in that the gap analysis represents a high-level, narrowly-focused comparison of the technical, physical, and administrative safeguards in place with how well they actually perform against a cyber attack. As such, the gap analysis can be thought of as introduction to potential vulnerabilities in a system, which is part of an overall risk analysis.[5] The gap analysis asks what your cyber capabilities are, what the major threats are, and what the differences are between the two. Additionally, you may want to consider what the potential impacts would be if a threat were realized.[1]

The gap analysis can also be looked at as measure of current safeguards in place vs. what industry best practice controls dictate. This may be done by choosing an industry standard security framework—we're using the NIST Cybersecurity Framework for this guide— and evaluating key stakeholder policies, responsibilities, and processes against that framework.[20]

5.3.7 Perform a risk analysis and prioritize risk based on threat, vulnerability, likelihood, and impact

With cybersecurity goals, asset inventory, and gap analysis in hand, its time to go comprehensive with risk assessment and prioritization. Regardless of whether or not you're hosting and transmitting PHI or other types of sensitive information, you'll want to look at all your cybersecurity goals, systems, and applications as part of the risk analysis.[4] Functions of risk analysis include, but are not limited to[2][5][7]:

- considering the operations supporting business goals and how those operations use technology to achieve them;

- considering the various ways the system functionality and entry points could be abused and compromised (threat modeling);

- comparing the current system's or component's architecture and features to various threat models; and

- compiling the risks identified during threat modeling and architecture analysis and prioritizing them based on threat, vulnerability, likelihood, and impact.

Additionally, as part of this process, you'll also want to examine the human element of risk in your business. How thorough are your background checks of new employees and third parties accessing your systems? How easy is it for them to access the software and the hardware? Is the principle of "least privilege" being used appropriately? Have any employee loyalties shifted drastically lately? Are the vendors supplying your IT and data services thoroughly vetted? These and other questions can supplement the human-based aspect of cybersecurity risk assessment.

5.3.8 Declare and describe objectives based on the outcomes of the above assessments

After performing all that research, it's finally time to distill it down into a clear set of cybersecurity objectives. Those objectives will act as the underlying core for the actions the business will take to develop policies, fill in security gaps, monitor progress, and educate staff. The objectives that come out of this step "should be specific, realistic, and actionable."[1] In a world where cyber threats are constantly evolving, being "100 percent secure against cyber threats" is an unrealistic goal, for example.[1]

One way to go about this process is to go back to the cybersecurity goals you created (see 5.1.3) and place your objectives under the goals they support. Perhaps one of your goals is to promote a culture of cybersecurity awareness among all employees and contractors. Under that goal you could list objectives such as "improve subject-matter expertise among leadership" and "support and encourage biannual cybersecurity training exercises throughout the business." You may also want to, at this point, make mention of what prioritization the objectives have and what progress measurement mechanisms can and should be put in place. Finally, work a certain level of adaptability into the objectives, not only in what they should achieve but also how they should be evaluated and updated. Technology, attack vectors, and even business needs can change rapidly. The objectives you develop should take this into consideration, as should the review and update policy for the cybersecurity plan itself (discussed later).

5.3.9 Identify policies for creation or modification concerning passwords, physical security, etc., particularly where gaps have been identified from the prior assessments and objectives

Say you previously noted your business has a few password and other access management policies in place, but they are relatively weak compared to where you want to be. If you haven't already, now is a good time to start tracking those and other policies that need to be updated or even created from scratch. Note that you may also discover additional policies that should be addressed during the next step of selecting and refining security controls. Consider performing this step in tandem with the next to gain the clearest idea of all the policy updates the business will require to meet its cybersecurity objectives.

5.3.10 Select and refine security controls for identification, protection, detection, response, and recovery based on the assessments, objectives, and policies above

Still need to complete this subsection.

(NIST security controls are used for this example plan)

5.4 Establish performance indicators and associated time frames

5.4.1 Determine baselines and indicators based on the assessments and objectives from the previous step

Your cybersecurity goals are formulated, their associated objectives are set, and security controls are selected. But how should you best measure their implementation, and over what sort of timeline should they be measured? This is where performance indicators come into play. A performance indicator is "an item of information collected at regular intervals to track the performance of a system."[21] They tend not to be perfect measures of performance, but performance indicators remain an important function of quality control and business management. There's also a social aspect to performance indicators: what is the implied message and behavioral implications of implementing such a monitoring system? Does the monitoring of the indicator, in the end, have a beneficial impact?[21]

Regardless of what industry you work in, deciding on the most appropriate indicators is no easy task. In March 2019, Axio CTO Jason Christopher spoke at a cybersecurity summit about security metrics (a metric is typically a number-based measurement within an indicator), with a focus on the energy industry. During that talk, he discussed various myths concerning collecting metric data for indicators, as well as the mixed success of tools such as heat maps and scorecards. After highlighting the difficulties, he gave a few pieces of useful advice. Among the more interesting suggestions he turned to was a security metrics worksheet to better define, understand, and track what you'll measure for your indicators. In his example, he used the EPRI's (Electric Power Research Institute) Cyber Security Metrics for the Electric Sector document, pulling an example metric and explaining how it was created. Among other aspects, their worksheet format includes an identifier for the metric, the associated organizational goal, and the associated cybersecurity control, which helps ensure the metric is aligned with organizational policy, existing terminology, and current best practices.[22][23]

Regardless of industry, you may find it useful to use similar worksheet documentation for the indicators you choose to use. Unfortunately, unlike the energy industry, many industries don't have a developed set of technical cybersecurity metrics. However, the ground that EPRI has already covered, plus insights gained during the security controls selection process (see 5.3.10), should aid you in choosing the most appropriate indicators. (Jason Christopher's description of the fields on the security metrics worksheet can be found at sans.org [PDF]. The EPRI cybersecurity metrics document can be downloaded for free at EPRI.com.) Whatever indicators you choose, be sure they are specific, measurable, actionable, relevant, and focused on a timely nature. In particular, keep the time frame of cybersecurity strategy development and implementation in mind when choosing indicators. If you expect full implementation to take three years but choose indicators outside that time frame, those indicators won't be actionable or timely.[1]

Finally, consider the advice of author and strategic adviser Bernard Marr that business shouldn't be run heavily on performance indicator data. This goes for the development of your indicators for cybersecurity success. Instead, he says, "the focus should be on selecting a robust set of value-adding indicators that serve as the beginning of a rich performance discussion focused on the delivery of your strategy." He continues with a reminder that real people and their actions are behind the indicators, which shouldn't be taken purely at face value.[24]

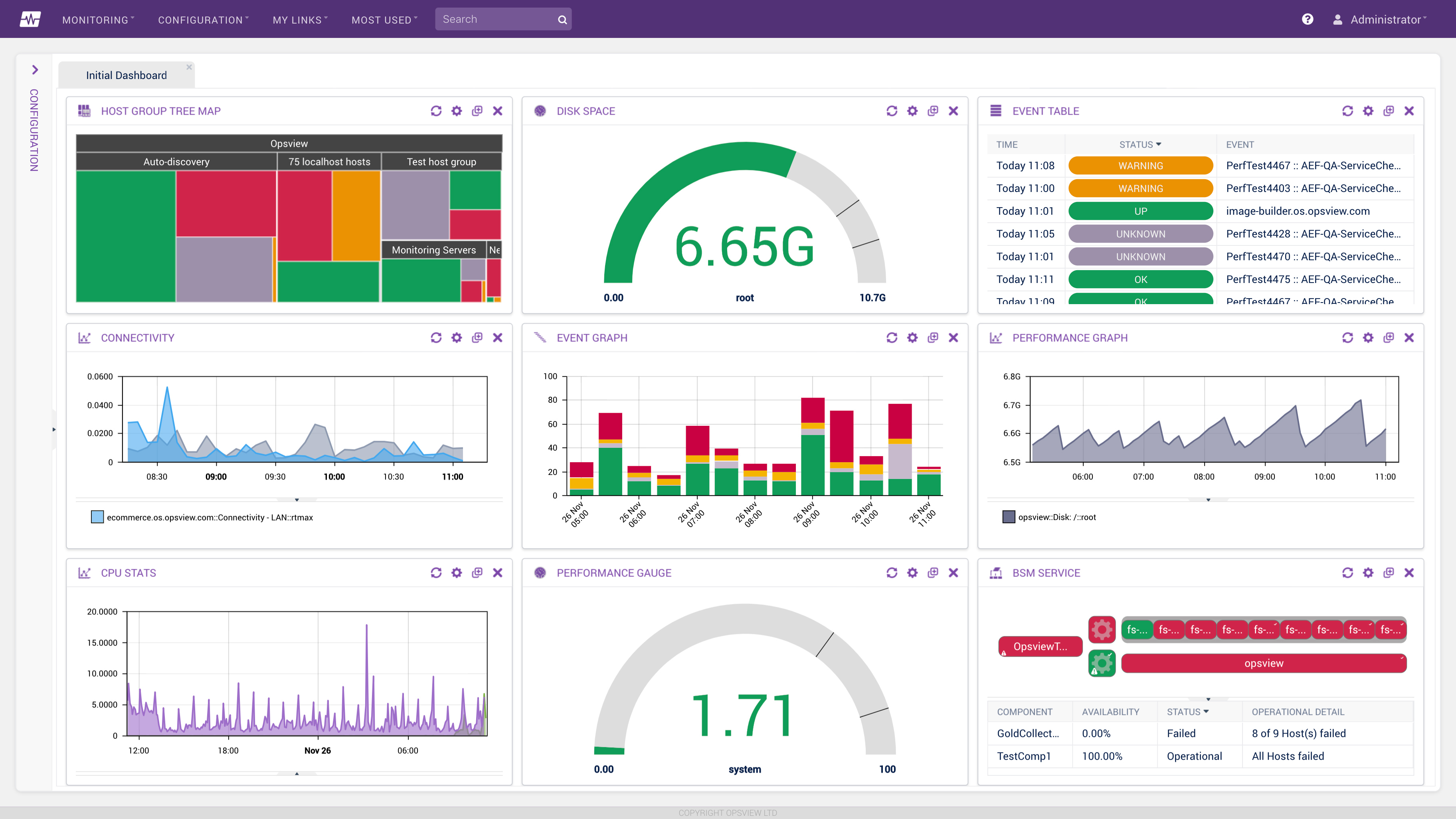

5.4.2 Determine how to measure progress and assess performance (quantitative vs. qualitative) and what tools are needed for such measurement and assessment

As previously mentioned, with indicators come metrics. But what tools will be used to acquire those metrics, and will those metrics measure quantitatively or qualitatively?[24] Are the measurement and monitoring tools available or will that have to acquired or developed? Can the data from intrusion detection systems and audit logs assist you in developing those metrics?[4] These and other questions must be asked when considering the numbers and measurements associated with an indicator. For many indicators, how to measure progress is relatively clear. A performance indicator such as "mean time to detect" (how long before your business becomes aware of a cybersecurity incident) will be measured in days. An indicator such as "risk classification" (is the risk minor, major, real, etc.) is measured using a non-numerical classification word. Refer to Black et al. and their Cyber security metrics and measures[25], as well as the HSSEDI (Homeland Security Systems Engineering and Development Institute) document Cyber Risk Metrics Survey, Assessment, and Implementation Plan[26], for more about cybersecurity metrics.

5.5 Identify key stakeholders

5.5.1 Determine what internal entities or people may act as cybersecurity stakeholders

At this point, you've probably already touched upon who's most interested or concerned about how cybersecurity is implemented within your organization. The first two steps of the plan call for defining cybersecurity goals, success, scope, and responsibilities. By extension, internal leadership with a significant stake in cybersecurity success has thus been identified. Additionally, the employees of an organization play an important role in developing or applying policies and procedures that come from your cybersecurity plan. You may have identified even more internal interests in seeing the plan succeed as well. Be sure at this point those stakeholders have been clearly identified. Also ensure their roles and responsibilities are clearly outlined and disseminated to the appropriate people, which further facilitates improved internal processes, communication, accountability, and preparedness.[1][2]

5.5.2 Determine what external (federal, state, local, and private) entities the business currently interacts with

You've also managed to identify what regulations affect your organization's operations, as well as who would be most affected by cybersecurity incidents. This and other areas are where you turn to identify your external stakeholders. While the identities of internal stakeholders are fairly easy to discern, determining external stakeholders can be a bit more challenging, and it will vary slightly depending on the nature of your business. A forensic science laboratory, for example, will have to consider the likes of federal agencies as stakeholders for reporting and accountability of sensitive data, whereas a public library addressing cybersecurity would have quite different external stakeholders. Be sure to look beyond government to software and equipment vendors, customers, and investors.

5.5.3 Define how those stakeholders shape the cybersecurity plan and its strategic goals

After identifying the "who," it's time to address the "how." Internal leadership is going to most strongly affect the cybersecurity plan and the organization's cybersecurity goals, and as such, you can readily define their impact. Regulatory bodies also represent clear stakeholder involvement in how policy is shaped, e.g. U.S. businesses handling PHI will need to conform to HIPAA data privacy regulations. How other stakeholders influence the plan and goals may be more difficult due to actual role (the typical employee arguably has only so much control over security) or internal politics (how leadership views investors' role in shaping cybersecurity policy). It may help to organize all stakeholders by their relationship to the cybersecurity effort (primary, secondary, key, etc.) while considering how those stakeholders will inevitably shape policy. The University of Kansas' Community Tool Box Chapter 7, Section 8 may be helpful for better identifying stakeholders and their interests.[27]

5.6 Determine resource needs

5.6.1 Determine whether sufficient in-house subject-matter expertise exists, and if not, how it will be acquired

Businesses come in many sizes, and not all have the in-house expertise to take the deep dive into cybersecurity. To be fair, the size of a business isn't the only determiner of IT resources. Hiring practices and hosting decisions for both software and IT (e.g., software as a service and infrastructure as a service vs. local hosting) may also impact the level of cybersecurity expertise in the business. Regardless, it's doubtlessly imperative to have some type of expertise involved in assisting with the implementation of your organization's cybersecurity plan. You probably have already addressed this during part two and three of making the cybersecurity plan, but now is an excellent time to double check that aside from any short-term expertise you're tapping into while formulating your plan, ensure you have long-term support for the implementation and monitoring of the plan's components.

5.6.2 Estimate time commitments and resource allocation towards training exercises, professional assistance, infrastructure, asset management, and recovery and continuity

The realities of business dictate that time is indeed valuable.[28] For a business to meet its primary goals, an investment of time and resources are required by those involved in the business. For a clinical laboratory, that means laboratorians performing analyses, making quality control checks, managing test results and reporting, and more. How much time do they truly need to commit in any given week to developing cybersecurity skills? And beyond the individual level, how much time does the business as a whole want to commit? With a need for training, infrastructure management, policy development and management, and recovery and continuity activities, your business has a lot to consider. These and other questions must be asked in relation to the realistic amount of resources available to the business and its personnel.

Here are a few additional questions to ask, as suggested by NARUC[1]:

- "What level of staff time should [a business] dedicate to learning about cybersecurity and developing skills necessary to achieve stated goals?"

- "Do staff need to become subject-matter experts, or is it enough that they are familiar with the language and terms?"

- "Do any staff need one-time training, ongoing training, certifications, or security clearances?"

- "Does the [business] have enough personnel to build and maintain relationships with [cybersecurity stakeholders]?"

5.6.3 Review the budget

Of course, the realities of business also dictate that money is a key component to business operations. That means budgeting that all important resource. What share of the overall budget will cybersecurity take, as proposed vs. what can realistically be allotted? This is where that previously conducted gap assessment and risk assessment comes into play again. You ended up identifying critical gaps in your current infrastructure and prioritizing cyber risks based on threat, vulnerability, likelihood, and impact. Those assessments guided your goals and objectives. Does your budget align with those goals and objectives? If not, what concessions must be made? If you're a small retail shop, antivirus software and firewalls may be enough. And as editor Cristina Lago notes in her 2019 article for CIO: "Be realistic about what you can afford. After all, you don’t need a huge budget to have a successful security plan. Invest in knowledge and skills."[3]

5.7 Develop a communications plan

5.7.1 Address the need for transparency in improving the cybersecurity culture

"If you look at it historically, the best ways to handle [cybersecurity] incidents is the more transparent you are the more you are able to maintain a level of trust. Obviously, every time there’s an incident, trust in your organization goes down. But the most transparent and communicative organizations tend to reduce the financial impact of that incident.” - McAfee CTO Ian Yip[3]

When your organization spreads the idea of improving cybersecurity and the culture around it, it shouldn't forget to talk about the importance of transparency. That includes the development process for the cybersecurity plan itself. Stakeholders will appreciate a forthright plan development and implementation strategy that clearly and concisely addresses the critical information system protections, monitoring, and communication that should be enacted.[1][3] Not only should internal communication about plan status be clear and regular, but also greater openness placed on promptly informing the affected individuals of cybersecurity risks and incidents. Of course, trust can be indirectly built up in other ways, such as ensuring training material is relevant and understandable, improving user management in critical systems, and ensuring communication barriers between people are limited.

5.7.2 Determine guidelines for everyday communication and mandatory reporting to meet cybersecurity goals

Sure, your IT specialists and system administrators know and understand the language of cybersecurity, but do the rest of your staff know and understand the topic enough to meet various cybersecurity business goals? One aspect of solving this issue involves ensuring clear, consistent communication and understand across all levels of the organization. (Another aspect, of course, is training, discussed below.) If everyone is speaking the same language, planning and implementation for cybersecurity becomes more effective.[1] This extends to everyday communications and reporting. Tips include:

- Clearly and politely communicate what consequences exist for those who violate cybersecurity policy, better ensuring compliance.[2][6]

- Consider developing and using communication and reporting templates for a variety of everyday emails, letters, and reports.[1]

- Don't forget to communicate organizational privacy policies and other security policies to third parties such as vendors and contractors.

- Don't forget to communicate changes of cybersecurity policy to all affected.

- Be flexible with the various routes of communication you can use; not everyone is diligent with email, for example.

5.7.3 Determine guidelines for handling or discussing sensitive information

Safely and correctly working with sensitive, protected, or confidential data in the organization is no simple task, requiring extra precautions, attention to regulations, and improved awareness throughout the workflow. In the clinical realm, organizations have PHI to worry about, while forensic labs must be mindful of working with classified data. Most businesses keep some sort of financial transaction data, and even your smallest of businesses may be working with trade secrets. These and other types of data require special attention by those creating a cybersecurity plan. Important considerations include staying informed of changes to local, state, and federal law; being vigilant with any role-based access to sensitive data; developing and enforcing clear policy on documenting and disposing cyber assets with such data; and developing boundary protection mechanisms for confining sensitive communications to trusted zones.[2] Cybersecurity standards and frameworks provide additional guidance in this realm.

5.7.4 Address incident reporting and response, as well as corrective action

As discussed earlier, fostering an environment of transparency in regards to cybersecurity matters is beneficial to the business. By extension, this includes properly disseminating notice of cybersecurity risks, breaches, and associated responses. Steve McGaw, the chief marketing officer for AT&T Business Solutions, had this to say about it in 2017[29]

When a breach is revealed, the attacked company is portrayed not as a victim, but as negligent and, in a subtle way, complicit in the event that ultimately exposed partners and customers. In short, it’s clearer than ever that cyberattacks can have an existential impact on companies. If customers don’t trust a company, then they simply won’t do business with them. These types of brand implications are indelible, and a communication strategy is invaluable.

This is where you decide how to communicate cybersecurity incidents and respond to them. McGaw and others offer the following advice in that regard[1][3][29][30]:

- Organize an incident response team of IT professionals, writers, leaders, and legal advisers and together develop protocols for how revelation of a cybersecurity incident should be handled, from the start.

- Ensure that upon an identified breach that the issue and it's likely impact are eventually clearly understood before communicating it to stakeholders. Communicating a hastily written, vague message creates more problems than solutions.

- Provide messaging on the solution (corrective action), not just the problem. Sometimes the solution is complex and difficult, but it's still beneficial to at least let stakeholders know action is being taken to correct the issue and limit its impact.

- Consider the use of playbooks, report templates, and training drills as part of your communication plan. Practice resolving security incidents with your assembled incident response team, and seek outside help when needed.

- When crafting your message, avoid jargon, use clear and simple language, be transparent (avoid "may" and "might"; be up-front), and keep your business values in context with the message.

- Don't forget to extend transparent messaging to internal stakeholders.

5.7.5 Address cybersecurity training methodology, requirements, and status tracking

While the topic of cybersecurity training could arguably receive its own section, training and communication planning go hand-in-hand. What is training but another form of imparting (communicating) information to others to act upon? And getting the word out about the cybersecurity plan and the culture it wants to promote is just another impetus for providing training to the relevant stakeholders.

The training methodology, requirements, and tracking used will largely be shaped by the goals and objectives detailed prior, as well as the budget allotted by management. For example, businesses with ample budget may be able to add new software firewalls and custom firmware updates to their system; however, small businesses with limited resources may get more out of training users on proper cyber hygiene than investing heavily in IT.[1] Regardless, addressing training in the workplace remains a critical aspect of your cybersecurity plan. As the NRECA notes[2]: "Insufficiently trained personnel are often the weakest security link in the organization’s security perimeter and are the target of social engineering attacks. It is therefore crucial to provide adequate security awareness training to all new hires, as well as refresher training to current employees on a yearly basis."

You'll find additional guidance on training recommendations and requirements by looking at existing regulations. Various NIST cybersecurity framework publications such as 800-53 and 800-171 (PDFs) may also provide insight into training.

5.8 Develop a response and continuity plan

5.8.1 Consider linking a cybersecurity incident response plan and communication tools with a business continuity plan and its communication tools

In the previous section, we discussed transparently and effectively communicating the details of a cybersecurity incident, as part of a communications plan. As it turns out, those communications also play a role in developing a recovery and continuity plan, which in turn helps limit the effects of a cyber incident. However, some planners end up confusing terminology, using "incident response" in place of either "business continuity" or "disaster recovery." While unfortunate, this gives you an opportunity to address both.

A cybersecurity incident response plan is a plan that focuses on the processes and procedures of managing the consequences of a particular cyber attack or other such incident. Traditionally, this plan has been the responsibility of the IT department and less the overall business. On the other hand, a business continuity plan is a plan that focuses on the processes and procedures of managing the consequences of any major disruption to business operations across the entire organization. A disaster recovery plan is one component of the business continuity plan that specifically addresses restoring IT infrastructure and operations after the major disruption. The business continuity plan looks at natural disasters like floods, fires and earthquakes, as well as other events, and it's usually developed with the help of management or senior leadership.[9][31]

All of these plans have utility, but consider linking your cybersecurity incident response plan with your new or existing business continuity plan. You may garner several benefits from doing so. In fact, some experts already view cyber incident response "as part of a larger business continuity plan, which may include other plans and procedures for ensuring minimal impact to business functions."[9][31][8] Stephanie Ewing of Delta Risk offers four tips in integrating cybersecurity incident recovery with business continuity. First, she suggests using a similar process approach to creating and reviewing your plans, including establishing an organizational hierarchy of the plans for improved understanding of how they work together. Second, Ewing notes that both plans speak in terms of incident classifications, response thresholds, and affected technologies, adding that it would be advantageous to share those linkages for consistency and improved collaboration. Similarly, linking the experience of operations in developing training exercises and drills with the technological expertise of IT creates a logical match in efforts to test both plans. Finally, Ewing examines the tendency of operations teams to use different communications tools and language than IT, creating additional problems. She suggests removing the walls and silos and establishing a common communication between the two planning groups to ensure greater cohesion across the enterprise.[8]

For the specifics of what should be contained in your recovery and continuity planning, you may want to turn to reference works such as Cybersecurity Incident Response, as well as existing incident response plans (e.g., University of Miami) and expert advice.

5.8.2 Include a listing of organizational resources and their criticality, a set of formal recovery processes, security and dependency maps, a list of responsible personnel, a (previously mentioned) communication plan, and information sharing criteria

A lot of this material has already been developed as part of your overall cybersecurity plan, but it is all relevant to developing incident response plans. Having the list of technological components and their criticality will help you create the organizational hierarchy of the various aspects of your incident response and business continuity plans. Having the formal recovery processes in place beforehand allows your organization to develop training exercises around them, increasing preparedness. Application dependency mapping allows you to "understand risk, model policy, create mitigation strategies, set up compensating controls, and verify that those policies, strategies, and controls are working as you intend to mitigate risk."[32] Knowing who's in charge of what aspect of recovery ensures a more rapid approach. And having a communication and information sharing strategy in place helps to limit rumors and transparently relate what happened, what's being done, and what the future looks like after the cyber incident.

5.9 Establish how the overall cybersecurity plan will be implemented

5.9.1 Detail the specific steps regarding how all the above will be implemented

Weeks, months, perhaps even years of planning have led you to this point: how do we go about implementing the details of our cybersecurity plan? It may seem the daunting process, but this is where management expertise comes in handy. A formal project manager should be taking the reigns of the implementation, as that person preferably has experience initializing change processes, evaluating milestones as realistic or flawed, implementing ad hoc revisions to the plan, and finalizing the processes and procedures for reporting and evaluating the implementation.[1] The manager also has the benefit of being able to ensure the implementation will stay true to the proposed budget and make the necessary adjustments along the way.[2]

5.9.2 State the major implementation milestones

In Martinelli and Milosevic's Project Management ToolBox: Tools and Techniques for the Practicing Project Manager, milestones and milestone charts are discussed as integral project management tools. They define a milestone as "a point in time or event whose importance lies in it being the climax point for many converging activities."[33] They go on to give examples of milestones, including deliverables, project phase transitions, extensive reviews, and external events. Deciding what the key milestones of plan implementation will be up to the project manager, but they'll likely consider traditional milestones or focus on the major synchronization and decision points along the entire process. This includes studying the dependencies in the various implementation steps and anticipating how they will converge, ensuring also that the milestones are adequately spaced and have received team input.[33]

5.9.3 Determine how best to communicate progress on the plan’s implementation

The project manager will also likely oversee dissemination of communications related to plan implementation. Without a doubt, internal stakeholders will want to be kept aware of the implementation status of the cybersecurity plan. When should IT go live with the improved firewall installation? Are the new password requirements going into effect later than expected? Has the training literature you handed out last week been updated to reflect the critical changes your staff had to make over the weekend? Keeping everyone in the loop will help build trust in the attempt to build cybersecurity culture into the workplace. This also means concise and comprehensible documentation is being made available and is updated as changes in implementation take place. This is all in addition to deciding how to best communicate implementation progress (e.g., reports, emails, meetings, project website).

5.10 Review progress

5.10.1 Monitor and assess the effectiveness of security controls

The planning is in the rear-view mirror, the implementation is complete, and your organization is nestled behind a warm layer of technological and process-based security. Pat yourselves on the back and call it "mission accomplished," right? Well, not quite. The mission of cybersecurity is never-ending, as is the adaptation and assault of cyber criminals. The final component of a successful cybersecurity plan involves monitoring and assessing the effectiveness of the plan, and updating it when necessary. This is where those performance indicators (5.4) you developed truly come into play. Based on your cybersecurity goals and objectives, those performance indicators are tied to monitoring systems, audit controls, and workflow processes. Questions worth asking include[2][3][4]:

- Do the indicators seem to be measuring what your organization intended?

- Are trends accurately being identified out of the data, or is the data simply confounding?

- Are the detection settings doing their job, or are attacks getting through that shouldn't be?

- Are appropriate cybersecurity test procedures and tools implemented and used by qualified personnel?

- Is enough data being captured and documented?

- Are emails and alerts actually being received and acted upon?

- Are too many false positives being generated?

5.10.2 Review how to capture and incorporate corrective action procedures and results

By seeking and blundering we learn. - Johann Wolfgang von Goethe

Your organization has sought out being more aware of cybersecurity issues and has enacted a plan and controls to fight against various cybersecurity threats. Yet during that process your organization has also hopefully learned that no one is 100 percent secure. Incidents happen. Control settings get overlooked. Attack vectors change. When these issues come up, it takes more than fixing the problem to improve a process or system. The incident, overlooked process, or new knowledge must be analyzed, documented, and disseminated in order for everyone to learn and improve. This is why the organization must—in addition to monitoring and assessing the plan's effectiveness—document occasions of "blundering" and incorporate any new observations or lessons (e.g., using an after-action report) back into the current plan.[1] Which leads to...

5.10.3 Determine how often to review and update the cybersecurity plan

How often should you review and update this labor of love and sacrifice your organization has developed? Some may argue that an annual review of the cybersecurity plan is enough, while others may insist such a review be biannual. In the end, the time frame will largely be an organizational decision that also could be revised over time based upon the results of your performance indicators and monitoring activities. What's important is that you 1. decide how often to review it, 2. declare who will be in charge of the review, 3. determine how and what opinions and data from stakeholders will be incorporated, and 4. how any changes will be disseminated into documentation and training programs.

5.10.4 Determine external sources for “lessons learned” and how to incorporate them for improving cybersecurity strategy

Your organization now recognizes the importance of incorporating after-action reports and internal lessons learned into the existing cybersecurity plan. But we don't only learn from our own "blundering." You're not operating in a vacuum; other businesses are out there having the same types of successes and failures. What have they learned, and what have they improved? Determine what outside sources you should look towards for said lessons. Most likely this will involve looking to events that transpired in your industry, e.g., clinical laboratories looking to the healthcare industry and retailers looking to other retail security failures. In the healthcare realm, Healthcare IT News has been tracking and conglomerating cybersecurity news, videos, inforgraphics, and projects for several years now. In the industrial world, Nozomi Metworks has been doing a respectable job of conglomerating cybersecurity news in multiple languages. In particular, focus on incorporating lessons learned that address an obvious gap in your cybersecurity infrastructure and plan.

6. Closing remarks

Appendix 1. A simplified description of NIST Cybersecurity Framework controls, with ties to LIMSpec

What follows is essentially a simplification of the NIST control descriptions found in NIST Special Publication 800-53, Revision 4: Security and Privacy Controls for Federal Information Systems and Organizations. As mentioned earlier, while this framework of security and privacy controls is tailored to federal systems and organizations, most of the "Low" baseline controls, as well as select "Moderate" and "High" baseline controls, are still worthy of consideration for non-federal systems and organizations. Also worth noting again is that if the NIST SP 800-53 controls and framework is too technical for your tastes, a simplified version was derived from 800-53 by NIST in the form of NIST Special Publication 800-171, Revision 1: Protecting Controlled Unclassified Information in Nonfederal Systems and Organizations. In addition to making the controls and methodology a bit easier to understand, NIST includes a mapping table in Appendix D of 800-171 which maps its security requirements to both NIST SP 800-53 and ISO/IEC 27001. As such, you're able to not only see how it connects to the more advanced document but also to the International Organization for Standardization's international standard "for establishing, implementing, maintaining and continually improving an information security management system within the context of the organization."[34]

The general format used in Appendix 1 is to first separate the control descriptions by their NIST family, then their control name. Then, a simplified description—with occasional outside references—is added, based on the original text. Finally, additional resources are included, where applicable. Those resources are typically based on references NIST used in making its framework, or additional resources that help you, the reader, gain additional context.

Finally, if you are implementing or have implemented information management software in your laboratory, you may also find links to LIMSpec in the additional resources. The LIMSpec has seen a handful of iterations over the years, but its primary goal remains the same: to provide software requirements specifications for the ever-evolving array of laboratory informatics systems being developed. We attempted to link NIST's security and privacy controls to specific software requirements specifications in LIMSpec. It should be noted that some 40+ NIST controls could not be directly linked to a software specification in LIMSpec. In almost every single case, those items reflect as organizational policy rather than an actual software specification. If a LIMSpec comparison was made, you'll find a link to the relevant section. If no LIMSpec comparison could be made, you'll see something like "No LIMSpec comp (organizational policy rather than system specification)."

In some cases the comparison may seem slightly confusing. For example, all NIST controls encouraging the establishment of policy and procedure are linked to LIMSpec 7.1 and 7.2. LIMSpec 7.1 states "the system shall be capable of creating, managing, and securely holding a variety of document types, while also allowing for the review and approval of those documents using version and release controls." To be clear, it's not that any particular software system itself conforms to the NIST controls specifying policies be created and managed. Rather, this particular software specification ensures that any software system built to meet the specification will provide the means for creating and managing policies and procedures, which in hand aids the organization in conforming to the NIST controls specifying policies be created and managed.

NOTE: Under "Additional resources," occasionally a guide, brochure, or blog post from a particular company will appear. That guide or brochure is added solely because it provides contextual information about the specific NIST control. The inclusion as a resource of such a guide, brochure, or blog post should not be considered an endorsement for the company that published it.

6.1 Access control

AC-1 Access control policy and procedure

This control recommends the organization develop, document, disseminate, review, and update an access control policy. Taking into account regulations, standards, policy, guidance, and law, this policy essentially details the security controls and enhancements "that specify how access is managed and who may access information under what circumstances."[35]

Additional resources:

- NIST Access Control Policy and Implementation Guides

- NIST Special Publications 800-12, page 59

- OWASP Access Control Cheat Sheet

- LIMSpec 7.1, 7.2

AC-2 Account management

This control recommends the organization develop a series of account management steps for its information systems. Among its many recommendations, it asks the organization to clearly define account types (e.g., individual, group, vendor, temporary, etc.), their associated membership requirements, and policy dictating how accounts should be managed; appoint one or more individuals to be in charge of account creation, approval, modification, compliance review, and removal; and provide proper communication to those account managers when an account needs to be modified, disabled, or removed.

Additional resources:

- AAA Technical Writing LLC Sample Account Management Policy

- NIST Special Publication 1800-18 (Draft)

- No LIMSpec comp (organizational policy rather than system specification)

AC-2 (3) Account management: Disable inactive accounts

This control enhancement recommends the system have the ability to automatically disable an inactive account after a designated period of time.

Additional resources:

AC-2 (4) Account management: Automated audit actions

This control enhancement recommends the system have the ability to automatically audit creation, modification, enabling, disabling, and removal actions performed on accounts, as well as notify designated individuals or roles of those actions.

Additional resources:

AC-2 (7) Account management: Role-based schemes

This control enhancement recommends the organization take additional action in regards to accounts with privileged roles. NIST defines privileged roles as "organization-defined roles assigned to individuals that allow those individuals to perform certain security-relevant functions that ordinary users are not authorized to perform." The organization should not only use a role-based mechanism for assigning privileges to an account, but also the organization should monitor the activities of privileged accounts and manage those accounts when the role is no longer appropriate.

Additional resources:

- LIMSpec 32.35 and 34.4

AC-2 (11) Account management: Usage conditions

This control enhancement recommends the system allow for the configuration of specific usage conditions or circumstances under which an account type can be used. Conditions or circumstances for account activity may include role, physical location, logical location, network address, or chronometric criterion (time of day, day of week/month).

Additional resources:

AC-3 Access enforcement

This control recommends the system be capable of enforcing system access based upon the configured access controls (policies and mechanisms) put into place by the organization. This enforcement could occur at the overall information system level, or be more granular at the application and service levels.

Additional resources:

- LIMSpec 32.25, 32.35, 34.4, and 35.3

AC-6 Least privilege

This control recommends the organization use the principle of "least privilege" when implementing and managing accounts in the system. The concept of least privilege essentially "requires giving each user, service, and application only the permissions needed to perform their work and no more."[36]

Additional resources:

- CISA Least Privilege

- Netwrix Best Practice Guide to Implementing the Least Privilege Principle

- LIMSpec 36.4

AC-6 (1) Least privilege: Authorize access to security functions

This control enhancement recommends the organization provide access to specific security-related functions and information in the system to explicitly authorized personnel. In other words, one or more specific system administrators, network administrators, security officers, etc. should be given access to configure security permissions, monitoring, cryptographic keys, services, etc. required to ensure the system is correctly protected.

Additional resources:

AC-6 (4) Least privilege: Separate processing domains

This control enhancement recommends the system provide separate processing domains in order to make user privilege allocation more granular. This essentially means that through using virtualization, domain separation mechanisms, or separate physical domains, the overall information system can create additional fine layers of access control for a particular domain.

Additional resources:

AC-6 (9) Least privilege: Auditing use of privileged functions

This control enhancement recommends the system perform auditing functions on any privileged functions that get executed in the system. This allows organizations to review audit records to ensure the effects of intentional or unintentional misuse of privileged functions is caught early and mitigated effectively.

Additional resources:

AC-7 Unsuccessful logon attempts

This control recommends the system be capable of not only enforcing a specific number of failed logon attempts in a given period of time, but also automatically locking or disabling an account until released by the system after a designated period of time, or manually by an administrator.

Additional resources:

- Microsoft "Account lockout threshold" (Specific to Windows 10, but information still broadly useful)

- LIMSpec 32.32

AC-8 System use notification

This control recommends the system be configurable to allow the creation of a system-wide notification message or banner before logon that provides vital privacy, security, and authorized use information related to the system. The message or banner should remain on the screen until acknowledged by the user and the user logs on. Note that the wording of such message or banner may require legal review and approval before implementation.

Additional resources:

AC-10 Concurrent session control

This control recommends the system be able to limit the number of concurrent (running at the same time) sessions (log ins) globally, for a given account type, for a given a user, or by using a combination of such limiters. NIST gives the example of wanting to tighten security by limiting the number of concurrent sessions for system administrators or users working in domains containing sensitive data.

Additional resources:

AC-11 Session lock

This control recommends the system be able to prevent further access to a system using a session lock, which activates after a defined period of inactivity or upon a user request. The session lock must be able to remain in place until the user associated with the session again goes through the system's identification and authentication process.

Additional resources:

AC-14 Permitted actions without identification or authentication

This control recommends the organization develop a list of user actions, if any, that can be performed on the system without going through the system's identification and authentication process. Any such list should be documented and provide supporting rationale as to why the authentication can be bypassed. This may largely pertain to public websites or other publicly accessible systems.

Additional resources:

- No LIMSpec comp (organizational policy rather than system specification)

AC-17 Remote access

This control recommends the organization develop and document a remote access policy that addresses each type of remote access allowed into the system. Remote access involves communicating with the system through an external network, usually the internet. The policy should address the usage restrictions, configuration requirements, connection requirements, and implementation rules for the approved methods (e.g., wireless, broadband, Bluetooth, etc.). Some sort of access enforcement process should take place prior to allowing remote access (see AC-3 for said access enforcement).

Additional resources:

- NIST Special Publications 800-46, Rev. 2

- NIST Special Publications 800-113

- NIST Special Publications 800-114, Rev. 1

- NIST Special Publications 800-121, Rev. 2

- No LIMSpec comp (organizational policy rather than system specification)

AC-17 (1) Remote access: Automated monitoring and control

This control enhancement recommends the system have the ability to monitor and control remote access methods. By enabling authorized individuals to audit the connection activity of remote users, compliance with remote access policies (see AC-17) can be ensured and cyber attacks caught early.

Additional resources:

AC-17 (2) Remote access: Protection of confidentiality and integrity using encryption

This control enhancement recommends the system have the ability to implement encryption mechanisms for remote access. This involves using "encryption to protect communications between the access device and the institution," using encryption "to protect sensitive data residing on the access device," or both.[37]

Additional resources:

- LIMSpec 21.12 and 35.1

AC-18 Wireless access

This control recommends the organization develop and document a wireless access policy, probably best done in conjunction with AC-17. NIST gives examples of wireless technologies such as microwave, packet radio, 802.11x, and Bluetooth. The policy should address the usage restrictions, configuration requirements, connection requirements, and implementation rules for the approved wireless technologies. Some sort of access enforcement process should take place prior to allowing a wireless connection to the system (see AC-3 for said access enforcement). In most cases this will be a built-in authentication protocol for the wireless network.

Additional resources:

- NIST Special Publications 800-97

- NIST Special Publications 800-121, Rev. 2

- NIST Special Publications 800-187

- No LIMSpec comp (organizational policy rather than system specification)

AC-19 Access control for mobile devices

This control recommends the organization develop and document a mobile device (e.g., smart phone, tablet, e-reader) use and access policy. The policy should address the usage restrictions, configuration requirements, connection requirements, and implementation rules for the approved wireless technologies. Some sort of access enforcement process should take place prior to allowing a wireless connection to the system (see AC-3 for said access enforcement).

Additional resources:

- NIST Special Publications 800-114, Rev. 1

- NIST Special Publications 800-124, Rev. 1

- NIST Special Publications 800-164, Draft

- No LIMSpec comp (organizational policy rather than system specification)

AC-20 Use of external information systems

This control recommends the organization develop and document a policy concerning the use of external information systems to access, process, store, and transmit data from the organization's system. External information systems include (but are not limited to) personal devices, private or public computing devices in commercial or public facilities, non-federal government systems, and federal systems not operated or owned by the organization. This includes the use of cloud-based service providers. The organization should consider the trust relationships already established with contractors and other third parties when developing this policy.

- No LIMSpec comp (organizational policy rather than system specification)

AC-22 Publicly accessible content

This control recommend the organization develop and document policy on the use and management of public-facing components of the system, typically the public website. This control ensures that sensitive, protected, or classified information is not accessible by the general public. The organizational policy should address who's responsible for posting information to the public-facing system; how to verify the information being posted does not contain sensitive, protected, or classified information; and how to monitor the public-facing system to ensure any non-public information is removed upon discovery.

- No LIMSpec comp (organizational policy rather than system specification)

6.2 Awareness and training

AT-1 Security awareness and training policy and procedures

This control recommends the organization develop, document, disseminate, review, and update security training policies and procedures. It asks organizations to not only address the purpose, scope, roles, responsibilities, and enforcement of security training but also to address how it will be implemented, reviewed, and updated.

Additional resources:

- NIST Special Publications 800-12, pages 59–60

- NIST Special Publications 800-50

- NIST Special Publications 800-100, pages 26–34

- LIMSpec 7.1, 7.2

AT-2 Security awareness training

This control recommends the organization provide the necessary basic security awareness training as part of initial training, as well as follow-up training, when the system changes, or at a specific mandated frequency. This broadly applies to all information system users and includes the use of training material, informational posters, security reminders and notices, system messages, and awareness events towards meeting the requirements of this control.

Additional resources:

AT-3 Role-based security training

This control recommends the organization provide the necessary role-specific security training to personnel with specific assigned security roles and responsibilities. The training shall occur before authorization to access the system is provided, as well as when the system changes or at a specific mandated frequency. This includes the use of training material, policy and procedure documents, role-based security tools, manuals, and other materials towards meeting the requirements of this control.

Additional resources:

AT-4 Security training records

This control recommends the organization document and monitor basic and role-specific security training activities and retain that information for a designated period of time. Note that record retention requirements may vary based on regulations and standards that affect the organization and its operations.

Additional resources:

- LIMSpec 8.1, 8.5, and 31.4

6.3 Audit and accountability

AU-1 Audit and accountability policy and procedures

This control recommends the organization develop, document, disseminate, review, and update audit and accountability policies and procedures. It asks organizations to not only address the purpose, scope, roles, responsibilities, and enforcement of audit and accountability action but also to address how those policies and procedures will be implemented, reviewed, and updated.

Additional resources:

- NIST Special Publications 800-12, page 60

- State of North Carolina Audit and Accountability Policy

- LIMSpec 7.1, 7.2

AU-2 Audit events

This control recommends the organization scrutinize the information system to ensure it's fully capable of auditing the events the organization requires to meet its business, cybersecurity, and regulatory goals. It also recommends the organization find common ground within other areas of the organization to improve selection of auditable events, provide rationale for their selection, and implement within the information system the selected auditable events at the recommended frequency or during a specific situation. NIST SP 800-53, Rev. 4 also notes: "Audit records can be generated at various levels of abstraction, including at the packet level as information traverses the network. Selecting the appropriate level of abstraction is a critical aspect of an audit capability and can facilitate the identification of root causes to problems."

Additional resources:

AU-3 Content of audit reports

This control recommends the system be capable of generating audit records that, at a minimum, provide who enacted an event, when it was enacted, where it occurred, what occurred, and what the outcome was. Regulations and standards may dictate what must be recorded beyond those aspects.

Additional resources:

AU-4 Audit storage capacity

This control recommends the organization allocate sufficient resources to ensure the storage capacity of the system is sufficient to hold all its audit records. What that storage capacity should be will be most heavily dictated by data retention regulations and standards (see AU-11), followed by available organizational resources to commit to long-term storage. Additional safeguards such as sending warning messages to designated personnel or system roles when storage space reaches a critical minimum may be useful.

Additional resources:

- No LIMSpec comp (organizational policy rather than system specification)

AU-5 Response to audit processing failures

This control recommends the system be able to alert specific personnel or system roles when an audit processing failure occurs and take action as specified by the organization. This action includes shutting down the system, overwriting the oldest audit record (because storage capacity is maxed), or discontinuing the generation of audit records. The system should also allow the organization to specify action differently for various types of failures.

Additional resources:

AU-6 Audit review, analysis, and reporting

This control recommends the organization, as part of policy, review, analyze, and report on the results from generated system audit records at defined frequencies, focusing on inappropriate or unusual activity that may compromise the security of the system. The finding may be reported to designated individuals within the organization, designated departments within the organization, or even regulatory bodies outside the organization.

Additional resources:

AU-6 (1) Audit review, analysis, and reporting: Process integration