Journal:Developing workforce capacity in public health informatics: Core competencies and curriculum design

| Full article title | Developing workforce capacity in public health informatics: Core competencies and curriculum design |

|---|---|

| Journal | Frontiers in Public Health |

| Author(s) | Wholey, Douglas R.; LaVenture, Martin; Rajamani, Sripriya; Kreiger, Rob.; Hedberg, Craig; Kenyon, Cynthia |

| Author affiliation(s) | University of Minnesota, Minnesota Department of Health, AllinaHealth |

| Editors | Caron, Rosemary M. |

| Year published | 2019 |

| Volume and issue | 6 |

| Page(s) | 124 |

| DOI | 10.3389/fpubh.2018.00124 |

| ISSN | 2296-2565 |

| Distribution license | Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International |

| Website | https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpubh.2018.00124/full |

| Download | https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpubh.2018.00124/pdf (PDF) |

|

|

This article should not be considered complete until this message box has been removed. This is a work in progress. |

Abstract

We describe a master’s level public health informatics (PHI) curriculum to support workforce development. Public health decision-making requires intensive information management to organize responses to health threats and develop effective health education and promotion. PHI competencies prepare the public health workforce to design and implement these information systems. The objective for a master's and certificate in PHI is to prepare public health informaticians with the competencies to work collaboratively with colleagues in public health and other health professions to design and develop information systems that support population health improvement. The PHI competencies are drawn from computer, information, and organizational sciences. A curriculum is proposed to deliver the competencies, and the results of a pilot PHI program are presented. Since the public health workforce needs to use information technology effectively to improve population health, it is essential for public health academic institutions to develop and implement PHI workforce training programs.

Keywords: public health informatics, public health practice, public health workforce, systems analysis, systems design

Introduction

With the increasing use of electronic data collection and storage, there is an increasing focus on information and knowledge management systems.[1] This results in public health workforce needs for public health informatics (PHI) professionals skilled in designing and implementing these systems. PHI professionals are those who “work in practice, research, or academia and whose primary work function is to use informatics to improve the health of populations.”[2] Recent studies highlight the need for informatics training in the public health workforce.[3][4] Similarly, the Council on Education for Public Health (CEPH) includes informatics as a foundational competency for accreditation of public health programs.[5][6] We build on the literature for developing informatics' savvy public health departments[7][8][9][10] and PHI core competency descriptions[2][11] to design a curriculum for a master's program in public health (MPH) and a certificate in PHI. The proposed curriculum differs from many existing health informatics programs by emphasizing the public health informatician's architectural role as a systems analyst linking public health users and information technology specialists by guiding the analysis and design of information systems. The focus is on: (a) problem definition for public health information systems (PHInfSys); (b) analyzing, designing, and implementing effective PHInfSys, such as surveillance, community health assessment, and population health management systems;[2][12] (c) encoding, collecting, curating, storing, retrieving, and analyzing data to create information; (d) assuring system and data governance, management, integration, confidentiality, and security; (e) creating and managing information technologies; and (f) collaborating in and leading inter-disciplinary and cross-cutting teams.

The foundation of public health is information, collected across a variety of sources, with the goal of generating and disseminating new knowledge and instituting actions to improve the public’s health. The need for public health education programs to be informed by current public health needs and employment opportunities has been long noted[13], as has the importance of establishing academic-practice links with public health agencies and training students in practice situations. In 2001, the need for PHI training was noted in an American Medical Informatics Association (AMIA) conference on developing a PHI agenda.[14] In 2012, AMIA revisited and updated these recommendations.[15] Both reports covered technical topics, such as information architecture and standards; governance and policy, including confidentiality and privacy; and workforce training. These needs are addressed by the PHI training program we describe.

The 2012 AMIA report noted that the “[t]he public health value chain is composed of business processes and use cases that describe the flow of data and information. Business processes describe how data, information, and knowledge are used by creating a framework that relates work activities to domains of public health function.”[15] PHI is a foundation for modernizing public health value chains, including public health department business processes[16], public health surveillance[17][18], public health emergency response, population health science[19], population health management[20], learning health systems[21], and public health research. PHI is an essential specialization that bridges the digital gap public health agencies face given growing expectations of service and preparedness. PHI integrates knowledge and skills from the information sciences (computer, information, organizational, and systems sciences) with public health expertise and “includes the conceptualization, design, development, deployment, refinement, maintenance, and evaluation of communication, surveillance, and information systems relevant to public health.”[22]

While PHI shares some core skills with other health informatics domains, such as bioinformatics or clinical and nursing informatics, it is distinct in necessitating integration of core informatics skills with public health systems, such as surveillance systems, community health assessment, disease/condition registries, and prevention programs in an overall framework of population health science. Public health informaticians (PHInf) differ from information technologists (ITs) because “[t]he focus of IT is to implement and operate information systems (hardware and software) that meet programmatic needs. In contrast, PHInf have a strategic and systems view of how information systems and technology can impact public health, such as how information systems can support public health decision-making. Unlike IT specialists, PHInf work within the larger context of how information systems function within the political, cultural, economic, and social environment and evaluate their impact within the broad sphere of public health. Thus, PHInf are in the unique position to understand how information systems can improve the practice and science of public health while contributing to the evidence-based practice of public health informatics.”[2]

Our paper focuses on training PHInf through MPH and certificate programs to provide them a foundation for a PHI professional career. The professional role is one of four related PHI roles identified by the PHI Institute, the Association of State and Territorial Health Officials, and the National Association of County and City Health Officials (NACCHO): executive; manager; professional; and clinical.[23] The curriculum design highlighted here focuses on the professional role because it is a frontline position that is the foundation for a career path through management to executive leadership.[24]

Our paper describes program design objectives and assumptions, design challenges, and core competencies. This overview provides context and prioritization for the program design.

PHI program design objectives and assumptions

The objective of PHI training is to educate PHInf with public health and PHI knowledge and skills that enable them to design and implement effective PHInfSys and have a successful PHI career. The design assumes that PHInf require competencies in (a) public health core competencies[25], functions, and systems (e.g., disease and environmental surveillance[18], population health management[20], and community health assessment[20][26][27]); (b) design thinking and systems analysis[28][29][30]; (c) computer, information, organizational, and systems sciences[22][31]; (d) evaluating information systems effectiveness[32]; and (e) teamwork and project management.

The core public health functions are assurance, assessment, and advocacy, which are used to maximize population health.[33] The PHI program design focuses on understanding how information systems achieve these functions rather than having a sub-goal focus on technological, computer science, or data mining aspects of PHI. Because PHI focuses on designing PHInfSys it has a foundation in design thinking.[28][29][30] Design thinking focuses on identifying problems as gaps in population health that information systems can help reduce by determining the root causes of those gaps and designing and implementing information systems to reduce population health gaps. Systems analysts are the architects who bridge the gap between users and technologies by understanding and translating user needs to system specifications and collaborating with technologists to implement those systems. The goal of systems analysis is to minimize the frequent disconnects between information system development and the usefulness of the resulting information systems[34][35] by avoiding simply automating existing inefficient information pathways.

To address these disconnects, effective systems analysis requires that PHInf are “well grounded in the fundamentals of organization theory, decision-making, teamwork and leadership, and research methods as well as current and emerging information systems technologies.”[36] PHInf also need the ability to design, implement, and evaluate information systems in multiple contexts, using approaches such as realistic evaluation and context-mechanism-outcome configurations (CMOc).[32]

Finally, PHInf need strong teamwork and project management skills because “PHI is cross-cutting. … Informaticians see the ‘big picture’ and ‘connects the dots’ across all of the other fields related to public health.”[12] Because information systems span diverse domains, the public health informatician requires the knowledge and skills to collaborate with diverse clients, lead systems analysis and development, and coordinate the diverse specialists implementing information systems, data use and privacy agreements, data and vocabulary standards, evaluation, training, and more.

In sum, PHInf require competencies in (a) public health core concepts and systems; (b) systems thinking and systems analysis; (c) computer, information, organizational, and systems sciences; (d) evaluating information systems effectiveness; and (e) the ability to work in and lead teams. These competencies provide the foundation for successfully progressing from being a PHI professional to PHI leadership positions.

PHI program design challenges

Public health informatics requires many different competencies. This can result in a laundry list of competencies that are not feasible to implement in a credit-constrained curriculum. Implementing a constrained educational program requires competency prioritization and trade-offs. There are three major challenges.

1. Content: PHI requires competencies in distinct domains—public health, health informatics, computer, information, and organizational sciences.[2][11][31] These include required core competencies for public health practice.[25] Health informatics and computer science focus on technical competencies. Information, systems, and organizational science competencies support solving population health problems because they provide systems analysis and design competencies needed to: (1) understand and translate user needs into system requirements and (2) create designs that can be implemented by ITs. Computer science competencies, such as modular decomposition, data structures, algorithms, programming languages, database theories, and system architectures are necessary to provide PHInf the knowledge and skills to communicate and collaborate effectively with ITs implementing PHInfSys.

2. Curricular independence vs. integrations: Siloed, independent courses maximize covering competency breadth, but they also rely on students to integrate across competencies. Courses integrating competencies develop the skills to apply informatics in public health. Examples of integrating competencies include using population health management and surveillance examples in technical courses, such as systems analysis, database, or health information exchange.

3. Declarative vs. procedural competencies: Declarative competencies are familiarity with analysis tools, such as requirements analysis, business process modeling, use cases, data flow diagrams, and entity relationship diagrams. Procedural competencies are being able to develop requirements, business process models, use cases, data flow diagrams, and entity relationship diagrams. Training in procedural competencies requires experiential practicums in which students apply declarative competencies. Increasing the emphasis on procedural competencies limits the breadth of declarative competencies that can be covered. The PHI design focuses on developing strong procedural competencies in system analysis because it is the core competency used to design and implement effective PHInf.

In sum, design challenges include decisions about content, integration (independent/integrated), and competency type (declarative/procedural) tradeoffs.

The proposed PHI design focuses on public health core competencies and organization/systems/information sciences related to analyzing, designing, implementing, and disseminating effective information systems in public health. Integrating competencies across courses maximizes the ability to apply skills in public health settings. For declarative and procedural learning, experiential practicums assure the ability to apply declarative knowledge. Elective credits support students in developing deeper skills in areas they are interested in, such as data management, analytics/data mining, GIS, visualization/communication, health information exchange[37], leading community health information exchange, or surveillance systems.[18]

PHI competencies

A PHI competency is a measurable and demonstrable knowledge related to the role “of developing innovative applications of technology and systems that address public health priorities by analyzing how information is organized and used and evaluating how this work contributes to the scientific field.”[2] The master’s level competencies for PHI professionals build on earlier work .[2][11] Not all competencies listed in earlier work are included for three reasons. First, the selected competencies need to fit into a typical MPH curriculum. While there are many desirable and important competencies, there is limited curriculum time. Second, some competencies reflect work in a practice setting that are not directly measurable (e.g., collaborating with others in program development, offering insights, contributing to decision-making, leading knowledge management). Third, some competencies are more managerial/executive competencies than professional competencies.

Core competencies

Core competencies include both public health and PHI. Public health core competencies[6][25] are addressed through the required MPH curriculum courses. This material is extended by integrating competencies related to public health systems, surveillance systems, population health management, community health assessment, eHealth, program monitoring, and evaluation in the PHI courses. For example, using electronic disease surveillance, population health management, community health assessment, and other public health systems as examples in the systems analysis courses educates students in the use of systems analysis to address common public health systems.[16][38]

Public health informatics competencies focus on systems analysis and data modeling. These include computer science and health informatics competencies related to nomenclature, standards, platforms, information architecture, interoperability, and systems analysis and data modeling, which require integration of material from organization/information systems/systems sciences, public health, and computer sciences. This integration builds the overall competency to design PHInfSys to solve problems in the public health domain. These competencies are noted as central to PHI. For example, “Redesigning Public Health Surveillance in an eHealth World” demonstrates the importance of systems analysis when it points out that “[d]efining requirements is a critical step in developing or acquiring an information system that will effectively support the work of the organization.”[38] Similarly, system selection depends “on the clarity and applicability of the use cases you define, and on determining prior to the demonstration how—based on what criteria—the use-case demonstrations will be judged”[38] as well as business process definitions.[38] The description of an informatics savvy health department states that “[i]nformation systems managers and staff require competency in creating formal system requirements.”[7] Requirements, use cases, and business process definitions are produced by systems analysis and require expertise in the system development life cycles (SDLC), national standards, and public policy related to informatics (e.g., meaningful use).[8] Complementary competencies are those that support systems analysis and data modeling[39], such as standards (e.g., HL7), nomenclature (e.g., ICD, CPT)[40], data flow diagrams, relational database theory, and query languages that inform system analysis and are used during implementation.

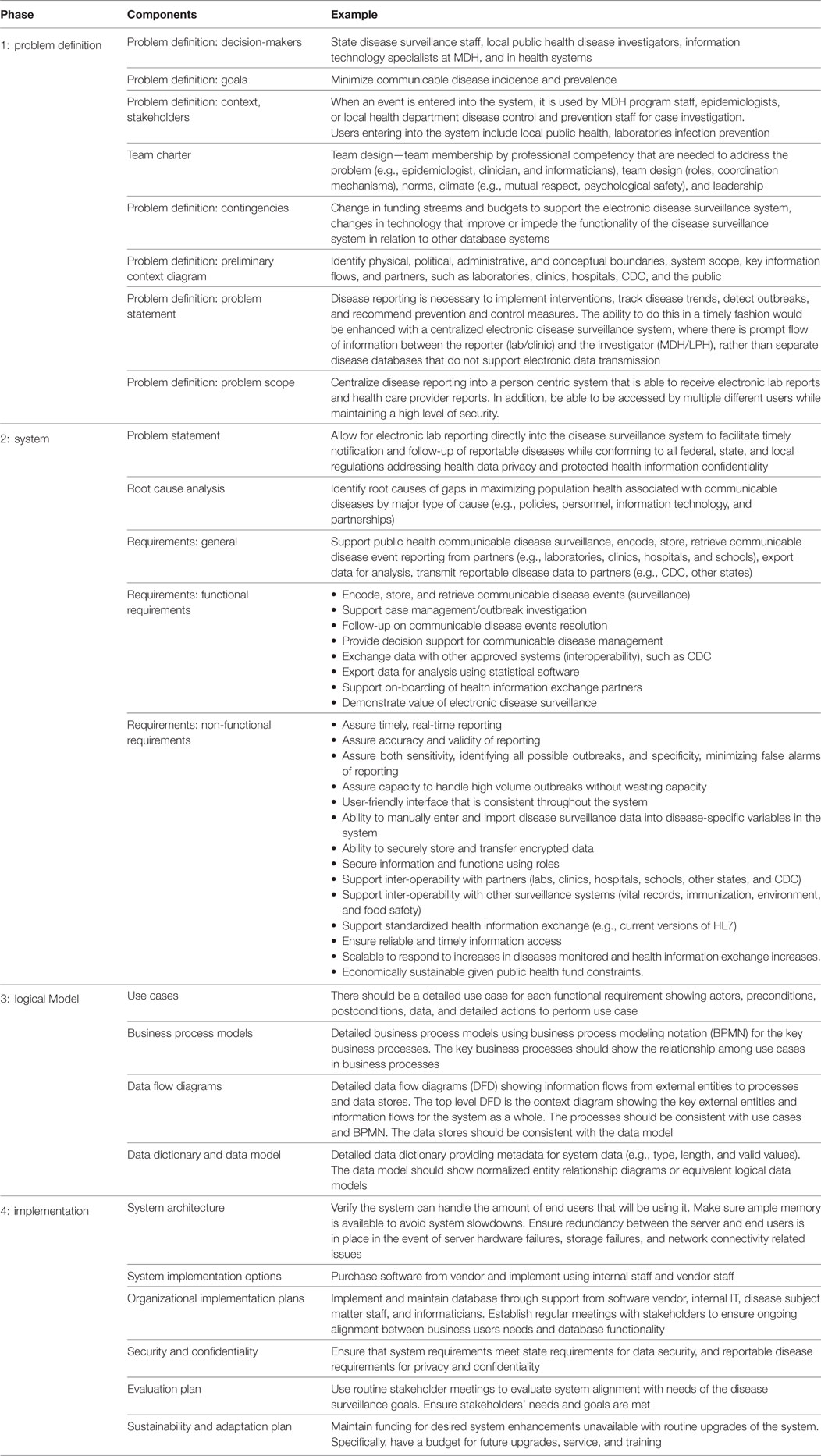

As an example, Table 1 illustrates systems analysis competencies for electronic disease surveillance. The goal of the system is to maximize population health by minimizing transmission of communicable diseases, which is done “through early identification, treatment, and resolution of health conditions.”[16] Systems analysis requires integrating competency in systems analysis with expertise in the system’s public health domain (e.g., electronic disease surveillance). The first analysis phase defines the problem, its decision-makers, context, and stakeholders. The second phase does a root cause analysis of gaps in population health related to communicable disease surveillance or system productivity and describes functional requirements, what tasks the communicable disease surveillance system supports, and nonfunctional requirements, criteria that the system has to meet. The third phase describes the logical model, the use cases corresponding to each functional requirement, business processes, data flows, and data model. Design and implementation is the final phase and builds on the analysis in the earlier phases to design and implement the information system that supports communicable disease surveillance staff in their activities.

|

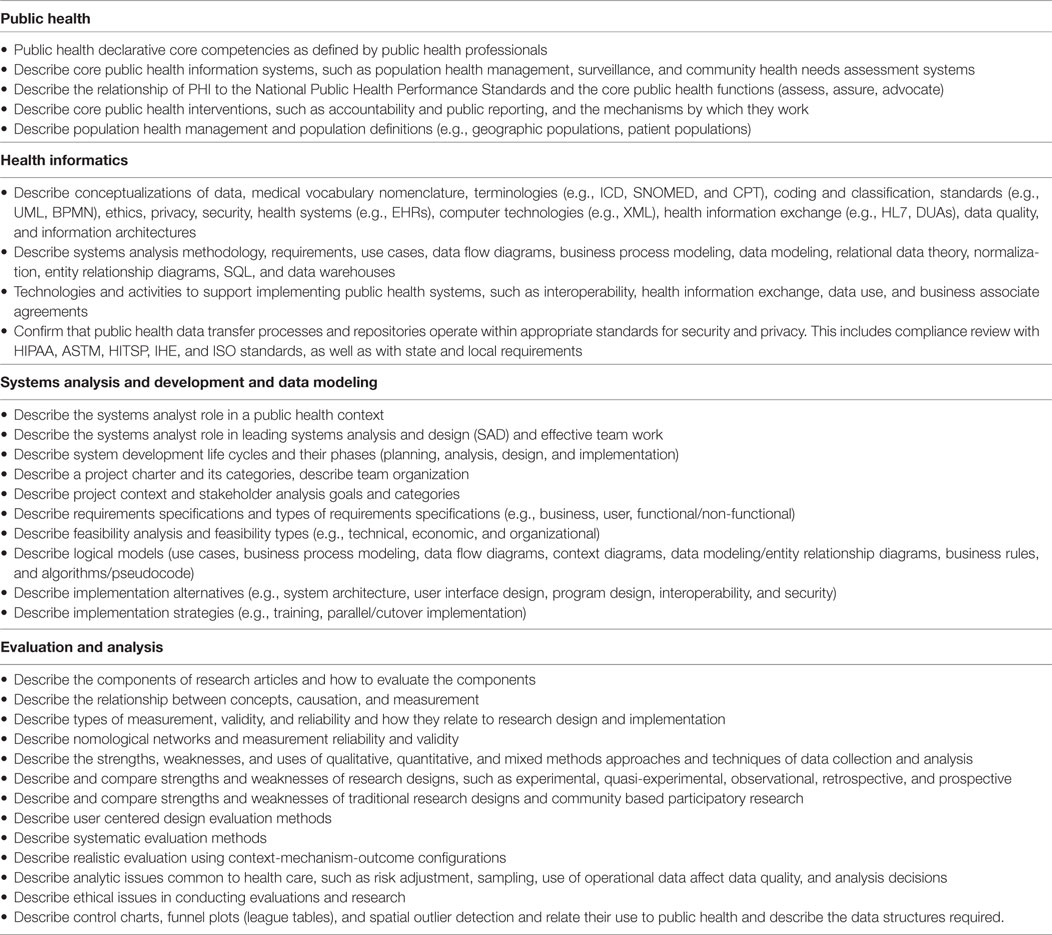

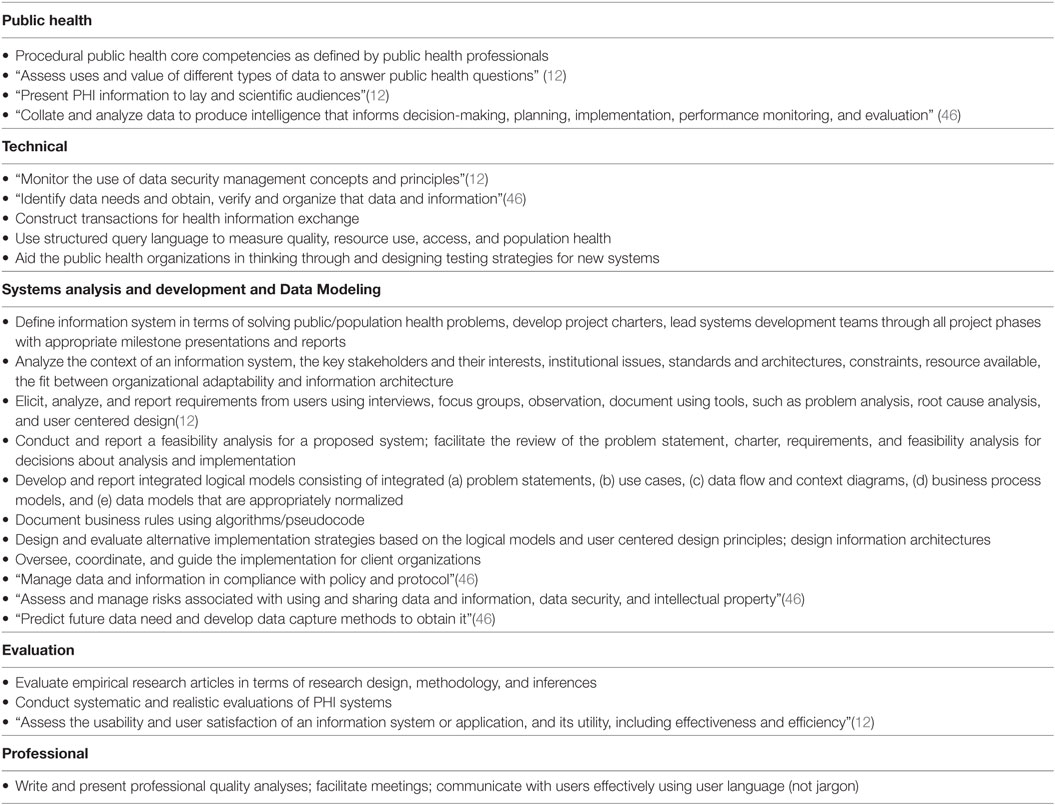

Declarative and procedural competencies

Tables 2 and 3 show the MPH PHI declarative and procedural competencies, which have a strong focus on those competencies also used in systems analysis and data modeling. These competencies reflect the informaticians’ architect role, which focuses on the problem definition and solving skills associated with defining problems, identifying requirements, building logical models, describing core features of information systems (use cases, data flows, data models, business processes), designing implementation alternatives, overseeing implementation, and facilitating user centered design and choice.

|

|

The declarative and procedural competencies also include a significant focus on research analysis and evaluation methods because PHInfSys are interventions designed to improve population health by improving quality, reducing costs, or both. Given the intervention aspect, a PHInf should have the competencies to be able to evaluate whether the public health information system accomplished its goals and how the information system functions in different contexts (realistic evaluation[32]). Effective evaluation requires enough expertise in public health systems, such as disease surveillance[17], quality improvement[41], public reporting, such as control charts, funnel plots (league tables)[42], and spatial outlier detection[43], to be able to assess how well they are implemented as well as their effectiveness. Competencies in assessing measurement validity and reliability are central to measuring population health.

References

- ↑ Freed, J.; Kyffin, R.; Rashbass, J. et al. (June 2014). "Knowledge strategy: Harnessing the power of information to improve the public's health". Public Health England. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/knowledge-strategy-harnessing-the-power-of-information-to-improve-the-publics-health.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5 2.6 Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, University of Washington's Center for Public Health Informatics (September 2009). "Competencies for Public Health Informaticians" (PDF). US Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Archived from the original on 13 June 2017. https://web.archive.org/web/20170613082955/https://www.cdc.gov/informaticscompetencies/pdfs/phi-competencies.pdf.

- ↑ Massoudi, B.L.; Chester, K.; Shah, G.H. (2016). "Public Health Staff Development Needs in Informatics: Findings From a National Survey of Local Health Departments". Journal of Public Health Management and Practice 22 (Suppl. 6): S58–S62. doi:10.1097/PHH.0000000000000450. PMC PMC5049962. PMID 27684619. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5049962.

- ↑ Beck, A.J.; Leider, J.P.; Coronado, F. et al. (2017). "State Health Agency and Local Health Department Workforce: Identifying Top Development Needs". American Journal of Public Health 107 (9): 1418-1424. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2017.303875. PMID 28727537.

- ↑ Calhoun, J.G.; Ramiah, K.; Weist, E.M. et al. (2008). "Development of a core competency model for the master of public health degree". American Journal of Public Health 98 (9): 1598-607. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2007.117978. PMC PMC2509588. PMID 18633093. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2509588.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Council on Education for Public Health (October 2016). "Accreditation Criteria: Schools of Public Health & Public Health Programs" (PDF). https://media.ceph.org/wp_assets/2016.Criteria.pdf.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 LaVenture, M.; Brand, B.; Ross, D.A. et al. (2014). "Building an informatics-savvy health department: Part I, vision and core strategies". Journal of Public Health Management and Practice 20 (6): 667–9. doi:10.1097/PHH.0000000000000149. PMID 25250757.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 LaVenture, M.; Brand, B.; Ross, D.A. et al. (2015). "Building an informatics-savvy health department II: Operations and tactics". Journal of Public Health Management and Practice 21 (1): 96–9. doi:10.1097/PHH.0000000000000179. PMID 25414962.

- ↑ LaVenture, M.; Brand, B.; Baker, E.L. (2017). "Developing an informatics-savvy health department: From discrete projects to a coordinating program - Part I: Assessment and governance". Journal of Public Health Management and Practice 23 (3): 325–7. doi:10.1097/PHH.0000000000000551. PMID 28350628.

- ↑ Brand, B.; LaVenture, M.; Baker, E.L. (2018). "Developing an informatics-savvy health department: From discrete projects to a coordinating program - Part III: Ensuring well-designed and effectively used information systems". Journal of Public Health Management and Practice 24 (2): 181–4. doi:10.1097/PHH.0000000000000756. PMID 29360696.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 Miner, K.; Alperin, M.; Brogan, C.W. et al. (28 February 2011). "Applied Public Health Informatics Curriculum - Preface and Modules". Public Health Informatics Institute. https://www.phii.org/resources/view/158/applied-public-health-informatics-curriculum-preface-and-modules.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 Fond, M.; Volmert, A.; Kendall-Taylor, N. (September 2015). "Making Public Health Informatics Visible: Communicating an Emerging Field" (PDF). FrameWorks Institute. https://www.frameworksinstitute.org/assets/files/health_care/phiistrategicmtgfinalseptember2015.pdf.

- ↑ Institute of Medicine (1988). "The Future of Public Health". The National Academies Press. doi:10.17226/1091. https://www.nap.edu/catalog/1091/the-future-of-public-health.

- ↑ Yasnoff, W.A.; Overhage, J.M.; Humphreys, B.L. et al. (2001). "A national agenda for public health informatics: summarized recommendations from the 2001 AMIA Spring Congress". JAMIA 8 (6): 535–45. PMC PMC130064. PMID 11687561. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC130064.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 Massoudi, B.L.; Goodman, K.W.; Gotham, I.J. et al. (2012). "An informatics agenda for public health: Summarized recommendations from the 2011 AMIA PHI Conference". JAMIA 19 (5): 688-95. doi:10.1136/amiajnl-2011-000507. PMC PMC3422819. PMID 22395299. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3422819.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 16.2 Public Health Informatics Institute (2008). Taking Care of Business: A Collaboration to Define Local Health Department Business Processes (2nd Printing ed.). Public Health Informatics Institute. https://www.phii.org/resources/taking-care-business-second-edition.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 McNabb, S.J.; Conde, J.M.; Ferland, L. et al. (2016). Transforming Public Health Surveillance: Proactive Measures for Prevention, Detection, and Response. Elsevier. ISBN 9780702063374.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 18.2 McNabb, S.J.N.; Rayland, P.; Sylvester, J. et al. (2017). "Informatics enables public health surveillance". Journal of Health Specialties 5 (2): 55–59. doi:10.4103/jhs.JHS_28_17.

- ↑ Bachrach, C.A.; Daley, D.M. (2017). "Shaping a New Field: Three Key Challenges for Population Health Science". American Journal of Public Health 107 (2): 251–52. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2016.303580. PMC PMC5227949. PMID 28075642. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5227949.

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 20.2 Kindig, D.A. (2007). "Understanding population health terminology". Milbank Q 85 (1): 139–61. doi:10.1111/j.1468-0009.2007.00479.x. PMC PMC2690307. PMID 17319809. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2690307.

- ↑ Friedman, C.; Rubin, J.; Brown, J. et al. (2015). "Toward a science of learning systems: A research agenda for the high-functioning Learning Health System". JAMIA 22 (1): 43–50. doi:10.1136/amiajnl-2014-002977. PMC PMC4433378. PMID 25342177. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4433378.

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 Yasnoff, W.A.; O'Carroll, P.W.; Koo, D. et al. (2000). "Public health informatics: improving and transforming public health in the information age". Journal of Public Health Management and Practics 6 (6): 67–75. PMID 18019962.

- ↑ Public Health Informatics Institute (25 April 2014). "Workforce Position Classifications and Descriptions". https://www.phii.org/resources/view/6423/workforce-position-classifications-and-descriptions. Retrieved 15 September 2017.

- ↑ Public Health Informatics Institute (April 2014). "Professional Level Public Health Informatician: Sample Position Description and Sample Career Ladder" (PDF). https://www.phii.org/sites/www.phii.org/files/resource/pdfs/Professional%20Sample%20Position%20AND%20Career%20Ladder.pdf. Retrieved 05 October 2017.

- ↑ 25.0 25.1 25.2 Council on Linkages Between Academia and Public Health Practice (26 June 2014). "Core Competencies for Public Health Professionals". pp. 24. http://www.phf.org/resourcestools/pages/core_public_health_competencies.aspx.

- ↑ Berndt, D.J.; Hevner, A.R.; Studnicki, J. et al. (2003). "The Catch data warehouse: Support for community health care decision-making". Decision Support Systems 35 (3): 367–84. doi:10.1016/S0167-9236(02)00114-8.

- ↑ Kindig, D.; Stoddart, G. (2003). "What is population health?". American Journal of Public Health 93 (3): 380-3. PMC PMC1447747. PMID 12604476. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1447747.

- ↑ 28.0 28.1 Simon, H.A. (1981). The Sciences of the Artificial (2nd ed.). MIT Press. ISBN 9780262191937.

- ↑ 29.0 29.1 Dym, C.L.; Agogino, A.M.; Eris, O. et al. (2013). "Engineering Design Thinking, Teaching, and Learning". Journal of Engineering Education 94 (1): 103–20. doi:10.1002/j.2168-9830.2005.tb00832.x.

- ↑ 30.0 30.1 Johansson‐Sköldberg, U.; Woodilla, J.; Çetinkaya, M. (2013). "Design Thinking: Past, Present and Possible Futures". Creativity and Innovation Management 22 (2): 121–46. doi:10.1111/caim.12023.

- ↑ 31.0 31.1 Friedman, C.P. (2012). "What informatics is and isn't". JAMIA 20 (2): 224–26. doi:10.1136/amiajnl-2012-001206.

- ↑ 32.0 32.1 32.2 Pawson, R.; Manzano-Santaella, A. (2012). "A realist diagnostic workshop". Evaluation 18 (2): 176–91. doi:10.1177/1356389012440912.

- ↑ Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2014). "The Public Health System & the 10 Essential Public Health Services". National Public Health Performance Standards. https://www.cdc.gov/publichealthgateway/publichealthservices/essentialhealthservices.html. Retrieved 08 May 2017.

- ↑ Harrison, M.I.; Koppel, R.; Bar-Lev, S. (2007). "Unintended Consequences of Information Technologies in Health Care—An Interactive Sociotechnical Analysis". JAMIA 14 (5): 542–49. doi:10.1197/jamia.M2384.

- ↑ Pentland, B.T.; Feldman, M.S. (2008). "Designing routines: On the folly of designing artifacts, while hoping for patterns of action". Information and Organization 18 (4): 235–250. doi:10.1016/j.infoandorg.2008.08.001.

- ↑ "Information Systems". Carnegie Mellon University. 2016. https://www.cmu.edu/information-systems/. Retrieved 29 January 2018.

- ↑ Dixon, B., ed. (2016). Health Information Exchange: Navigating and Managing a Network of Health Information Systems. Academic Press. doi:9780128031353.

- ↑ 38.0 38.1 38.2 38.3 Public Health Informatics Institute (June 2012). "Redesigning Public Health Surveillance in an eHealth World". Public Health Informatics Institute. https://www.phii.org/resources/view/1186/redesigning-public-health-surveillance-ehealth-world.

- ↑ Dennis, A.; Wixom, B.H.; Roth, R.M. (2015). Systems Analysis and Design (6th ed.). Wiley. ISBN 9781118897843.

- ↑ Hammond, W.E.; Jaffe, C.; Cimino, J.J. et al. (2014). "Standards in Biomedical Informatics". In Shortliffe, E.H.; Cimino, J.J.. Biomedical Informatics (4th ed.). Springer. ISBN 9781447144748.

- ↑ Woodall, W.H. (2006). "The Use of Control Charts in Health-Care and Public-Health Surveillance". Journal of Quality Technology 38 (2): 89–104. doi:10.1080/00224065.2006.11918593.

- ↑ Dover, D.C.; Schopflocher, D.P. (2011). "Using funnel plots in public health surveillance". Population Health Metrics 9: 58. doi:10.1186/1478-7954-9-58.

- ↑ Sherman, R.L.; Henry, K.A.; Tannenbaum, S.L. et al. (2014). "Applying spatial analysis tools in public health: An example using SaTScan to detect geographic targets for colorectal cancer screening interventions". Preventing Chronic Disease 11: E41. doi:10.5888/pcd11.130264. PMC PMC3965324. PMID 24650619. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3965324.

Notes

This presentation is faithful to the original, with only a few minor changes to presentation. A few grammar and spelling errors were also corrected. In some cases important information was missing from the references, and that information was added. Reference 2 and 11 in the original are unintentionally duplicated; we've removed a duplicate for this version. The same happened with reference 26 and 38 in the original, and it too was not duplicated for this version.