Journal:Bioinformatics education in pathology training: Current scope and future direction

| Full article title | Bioinformatics education in pathology training: Current scope and future direction |

|---|---|

| Journal | Cancer Informatics |

| Author(s) | Clay, Michael R.; Fisher, Kevin E. |

| Author affiliation(s) | St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital, Baylor College of Medicine, Texas Children’s Hospital |

| Primary contact | Email: Kevin dot Fisher at bcm dot edu |

| Year published | 2017 |

| Volume and issue | 16 |

| Page(s) | 1–6 |

| DOI | 10.1177/1176935117703389 |

| ISSN | 1176-9351 |

| Distribution license | Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International |

| Website | http://insights.sagepub.com/ |

| Download | http://insights.sagepub.com/redirect_file.php (PDF) |

|

|

This article should not be considered complete until this message box has been removed. This is a work in progress. |

Abstract

Training anatomic and clinical pathology residents in the principles of bioinformatics is a challenging endeavor. Most residents receive little to no formal exposure to bioinformatics during medical education, and most of the pathology training is spent interpreting histopathology slides using light microscopy or focused on laboratory regulation, management, and interpretation of discrete laboratory data. At a minimum, residents should be familiar with data structure, data pipelines, data manipulation, and data regulations within clinical laboratories. Fellowship-level training should incorporate advanced principles unique to each subspecialty. Barriers to bioinformatics education include the clinical apprenticeship training model, ill-defined educational milestones, inadequate faculty expertise, and limited exposure during medical training. Online educational resources, case-based learning, and incorporation into molecular genomics education could serve as effective educational strategies. Overall, pathology bioinformatics training can be incorporated into pathology resident curricula, provided there is motivation to incorporate institutional support, educational resources, and adequate faculty expertise.

Keywords: Bioinformatics, informatics, residency, education, pathology, training

Introduction

Anatomic pathology (AP) and clinical pathology (CP) residents, fellows, and faculty dedicate countless hours in structured training environments equipped with textbooks, scientific literature, and professional expertise to achieve proficiency in the histopathologic diagnosis of disease and/or interpretation of laboratory data. With the emergence of genomics data and clinical data warehouses, laboratory professionals are now tasked with managing, interpreting, and leveraging data of unprecedented complexity. These complex data necessitate that educators rethink the skills and knowledge required for a graduating trainee to practice in the “information age” of diagnostic medicine.

Bioinformatics is defined as the management, acquisition, manipulation, and presentation of complex biological data sets, and clinical informatics is the application of information management in health care to promote safe, efficient, effective, personalized, and responsive care. Given the breadth of these definitions, it is not surprising that defining aspects germane to clinical training is a nontrivial task. In molecular pathology, in particular, these definitions are intricately linked; e.g., computational scripts manipulate raw data such that pathologists can review and interpret for clinical reporting. Here, we highlight the requisite baseline skill set a pathologist should acquire during training to remain facile in bioinformatics and still fulfill the necessary requirements to graduate from accredited pathology training programs. A few key questions, barriers, and proposed solutions to incorporate bioinformatics into general residency education will also be discussed.

Informatics education in pathology residency

The American College of Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) is a private organization that oversees all accredited medical residency training in the United States. Their primary role is to standardize program requirements and provide operational standards for the sponsoring institution, training hospitals, faculty and program directors, program resources, and duty hours.[1] Also, the ACGME determines educational milestones that serve as specialty-specific data to facilitate improvements to curricula and resident performance and demonstrate the effectiveness of graduate medical education in meeting the needs of the public.[2] Sponsoring institutions receive funds from the federal government to cover the costs of training physicians, and ACGME-accredited residents’ and fellows’ salaries are allocated from these monies. Notably, sponsoring institutions must demonstrate compliance with the ACGME’s educational recommendations to maintain accreditation and receipt of the federal funds.

The American Board of Pathology (ABP) partners with the ACGME to ensure that accredited pathology programs provide their trainees with the necessary requisites to become board eligible for the AP, CP, AP/CP, or AP/neuropathology (AP/NP) examinations, and all potential ABP examinees must complete 36 to 48 months of full-time training in an ACGME-accredited pathology program. Each trainee must receive at least 24 months of AP-only or CP-only training or 18 months each of structured AP and CP training. The remaining 12 months is flexible and may include AP, CP, or research rotations (up to six months). Furthermore, AP board-eligible examinees must complete at least 50 autopsies by the time the application for certification is submitted.[3] An example of a typical 48-month AP/CP curriculum is provided in Table 1.

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

For informatics education, the ACGME requires that all AP, CP, and combined AP/CP residents gain exposure to clinical informatics during their pathology training. The informatics educational milestones state that a trainee should be able to explain, discuss, classify, and apply clinical informatics by participating in operational and strategy meetings, troubleshooting with information technology staff, and applying informatics skills to laboratory management and integrative bioinformatics (e.g., aggregate multiple data sources and multiple data analysis services).[4][5] As a result of these recommendations, formal clinical informatics rotations have been widely incorporated into pathology residency training programs over the past several years, and some institutions have implemented clinical informatics fellowship programs to facilitate board certification in this subspecialty.

Barriers to bioinformatics education

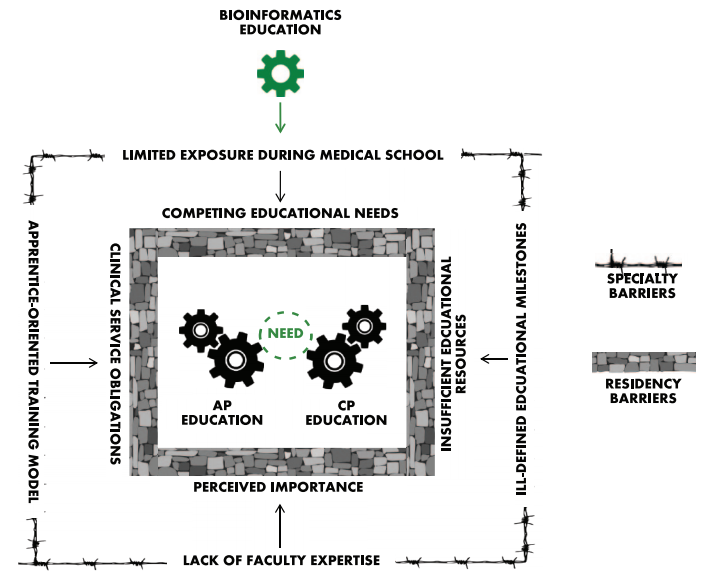

Devising strategies to address bioinformatics education is a complex issue, as there are barriers unique to both the specialty of pathology and residency training in general that must be addressed before bioinformatics can be effectively assimilated into routine pathology education. The key barriers are summarized in Figure 1 and discussed in detail here.

|

The ACGME allows each training program to create and implement its own educational content, and this practice inherently leads to discrepant exposure depending on the demands of other clinical services, faculty expertise, and departmental resources of the individual training programs. Pathology Informatics Essentials for Residents (PIER) is an excellent educational resource that highlights the importance of clinical informatics to the practice of pathology and provides a flexible pathology informatics curriculum and instructional framework that assist training residents in critical pathology informatics knowledge and skills per the ACGME recommended milestones.[6] However, for context, clinical informatics represents only one of the 27 ACGME pathology-specific milestones, and although the PIER topics and educational activities are ideal for instruction in clinical informatics, true bioinformatics topics comprise only a quarter of the 38 clinical informatics master list items. Together, the proposed time allocated to bioinformatics education translates to roughly 0.8% of an entire 48-month AP/CP residency training, or at most 10 days.

The combination of ill-defined educational milestones and limited allocated training time has attributed to underdeveloped and non-standardized bioinformatics educational materials for pathology residents. Ideally, the abovementioned resources could be supplemented with patient-centered, case-based learning modules that would allow trainees the opportunity to work through relevant clinical scenarios. Case-based materials are widely used for training residents in molecular genomic pathology[7] and clinical informatics.[8] However, we are currently unaware of standardized case-based learning materials that are specific to bioinformatics.

Fundamentally, residents “learn their trade” in an apprenticeship model under the tutelage of faculty with expertise in the practice and science of medicine, and as clinical service providers, residents “learn by doing.” For example, in pathology, AP residents gross surgical specimens and extensively study hematoxylin and eosin slides under the light microscope to formulate independent histopathologic diagnoses that are discussed directly with the supervising faculty. Likewise, CP residents work with faculty in secondary roles to interpret serum protein electrophoresis gels, manage transfusion reactions, or a host of other patient-directed finite tasks. Ultimately, this training model dominates almost all medical residency education because it seamlessly integrates trainees into patient care roles that align with the educational mission of the ACGME and the clinical and financial missions of the sponsoring institutions. As a result, residents staff and manage clinical services preferentially over other educational endeavors.

However, bioinformatics education is ill-suited for the clinical service apprenticeship model. Bioinformatics is not a clinical service that residents can receive bioinformatics cases, work up those cases, generate clinical reports, discuss and finalize the reports with the attending (e.g., “sign-out”), bill the patient for clinical services, and repeat the process the next day. Bioinformatics is a data-based discipline where the scope of work is anchored in application projects that may take weeks, months, or even years to materialize in any meaningful manner. Furthermore, the apprentice model requires experienced faculty which may or may not be readily accessible for all pathology trainees. Clinical faculty with limited bioinformatics knowledge, experience, or training may not recognize the importance of bioinformatics education and are therefore more likely to prioritize educational efforts toward clinical services. It is also impractical to assume that one or two informatics faculty members can train all residents in bioinformatics principles, particularly given the aforementioned limited time available (10 days).

There are other systematic factors that impede the incorporation of bioinformatics education into standard pathology curricula. In recent years, medical schools have transitioned from traditional discipline-based didactic curricula to problem-based learning curricula[9][10], most of which offer limited structured informatics education.[11] Furthermore, as an unintended consequence, the principles of histopathology and laboratory medicine were marginalized to electives or abandoned entirely.[12][13] Thus, medical school graduates not only lack exposure to basic bioinformatics principles but also lack exposure to basic principles in pathology which are necessary to function as a competent pathology resident. Therefore, basic histopathology and laboratory medicine principles immediately arise as competing educational needs even at the earliest stages of training.

Acknowledgements

Author contributions

MRC and KEF conceived and wrote the manuscript. All authors reviewed and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Disclosures and ethics

As a requirement of publication, author(s) have provided to the publisher signed confirmation of compliance with legal and ethical obligations including but not limited to the following: authorship and contributorship, conflicts of interest, privacy and confidentiality, and (where applicable) protection of human and animal research subjects. The authors have read and confirmed their agreement with the ICMJE authorship and conflict of interest criteria. The authors have also confirmed that this article is unique and not under consideration or published in any other publication, and that they have permission from rights holders to reproduce any copyrighted material. Any disclosures are made in this section. The external blind peer reviewers report no conflicts of interest.

Declaration of conflicting interests

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- ↑ "ACGME Program Requirements for Graduate Medical Education in Anatomic Pathology and Clinical Pathology" (PDF). Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education. July 2017. https://www.acgme.org/Portals/0/PFAssets/ProgramRequirements/300_pathology_2017-07-01.pdf. Retrieved 09 August 2017.

- ↑ "Pathology - Milestones". Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education. https://www.acgme.org/Specialties/Milestones/pfcatid/18/Pathology. Retrieved 31 October 2016.

- ↑ "Combined Anatomic Pathology and Clinical Pathology (AP/CP)". The American Board of Pathology. http://www.abpath.org/index.php/to-become-certified/requirements-for-certification?layout=edit&id=156. Retrieved 13 January 2017.

- ↑ Naritoku, W.Y.; Alexander, C.B. (2014). "Pathology milestones". Journal of Graduate Medical Education 6 (1 Suppl 1): 180–181. doi:10.4300/JGME-06-01s1-10. PMC PMC3966611. PMID 24701281. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3966611.

- ↑ Naritoku, W.Y.; Alexander, C.B.; Bennett, B.D. et al. (2014). "The pathology milestones and the next accreditation system". Archives of Pathology & Laboratory Medicine 138 (3): 307–15. doi:10.5858/arpa.2013-0260-SA. PMID 24576024.

- ↑ Henricks, W.H.; Karcher, D.S.; Harrison, J.H. et al. (2016). "Pathology Informatics Essentials for Residents: A flexible informatics curriculum linked to Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education milestones". Journal of Pathology Informatics 7: 27. doi:10.4103/2153-3539.185673. PMC PMC4977974. PMID 27563486. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4977974.

- ↑ Schrijver, I., ed. (2011). Diagnostic Molecular Pathology in Practice. Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg. pp. 339. doi:10.1007/978-3-642-19677-5. ISBN 9783642196768.

- ↑ Hassell, L.A.; Blick, K.E. (2016). "Training in Informatics: Teaching Informatics in Surgical Pathology". Clinics in Laboratory Medicine 36 (1): 183-97. doi:10.1016/j.cll.2015.09.014. PMID 26851672.

- ↑ Polyzois, I.; Claffey, N.; Mattheos, N. (2010). "Problem-based learning in academic health education: A systematic literature review". European Journal of Dental Education 14 (1): 55-64. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0579.2009.00593.x. PMID 20070800.

- ↑ Burgess, A.W.; McGregor, D.M.; Mellis, C.M. (2014). "Applying established guidelines to team-based learning programs in medical schools: A systematic review". Academic Medicine 89 (4): 678–88. doi:10.1097/ACM.0000000000000162. PMC PMC4885587. PMID 24556770. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4885587.

- ↑ Banerjee, R.; George, P.; Priebe, C.; Alper, E. (2015). "Medical student awareness of and interest in clinical informatics". JAMIA 22 (e1): e42–7. doi:10.1093/jamia/ocu046. PMID 25726567.

- ↑ Smith, B.R.; Kamoun, M.; Hickner, J. (2016). "Laboratory Medicine Education at U.S. Medical Schools: A 2014 Status Report". Academic Medicine 91 (1): 107–12. doi:10.1097/ACM.0000000000000817. PMC PMC5480607. PMID 26200574. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5480607.

- ↑ Laposata, M. (2016). "Insufficient Teaching of Laboratory Medicine in US Medical Schools". Academic Pathology 3: 1–2. doi:10.1177/2374289516634108. PMC PMC5497899. PMID 28725761. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5497899.

Notes

This presentation is faithful to the original, with only a few minor changes to presentation, grammar, and spelling. In some cases important information was missing from the references, and that information was added. In one case (the first citation), the original citation URL was dead, and an updated URL was substituted.