Journal:Smart electronic laboratory notebooks for the NIST research environment

| Full article title | Smart electronic laboratory notebooks for the NIST research environment |

|---|---|

| Journal | Journal of Research of NIST |

| Author(s) | Gates, R.S.; McLean, M.J.; Osborn, W.A. |

| Author affiliation(s) | National Institute of Standards and Technology |

| Primary contact | Email: ulrich.dirnagl@charite.de |

| Editors | william dot osborn at nist dot gov |

| Year published | 2015 |

| Volume and issue | 120 |

| Page(s) | 293–303 |

| DOI | 10.6028/jres.120.018 |

| ISSN | 2165-7254 |

| Distribution license | Public domain |

| Website | https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4730679/ |

| Download | http://nvlpubs.nist.gov/nistpubs/jres/120/jres.120.018.pdf (PDF) |

|

|

This article should not be considered complete until this message box has been removed. This is a work in progress. |

Abstract

Laboratory notebooks have been a staple of scientific research for centuries for organizing and documenting ideas and experiments. Modern laboratories are increasingly reliant on electronic data collection and analysis, so it seems inevitable that the digital revolution should come to the ordinary laboratory notebook. The most important aspect of this transition is to make the shift as comfortable and intuitive as possible, so that the creative process that is the hallmark of scientific investigation and engineering achievement is maintained, and ideally enhanced. The smart electronic laboratory notebooks described in this paper represent a paradigm shift from the old pen and paper style notebooks and provide a host of powerful operational and documentation capabilities in an intuitive format that is available anywhere at any time.

Keywords: cloud, collaboration, computing, ELN, electronic, laboratory, notebook, SELN, tablet

Introduction

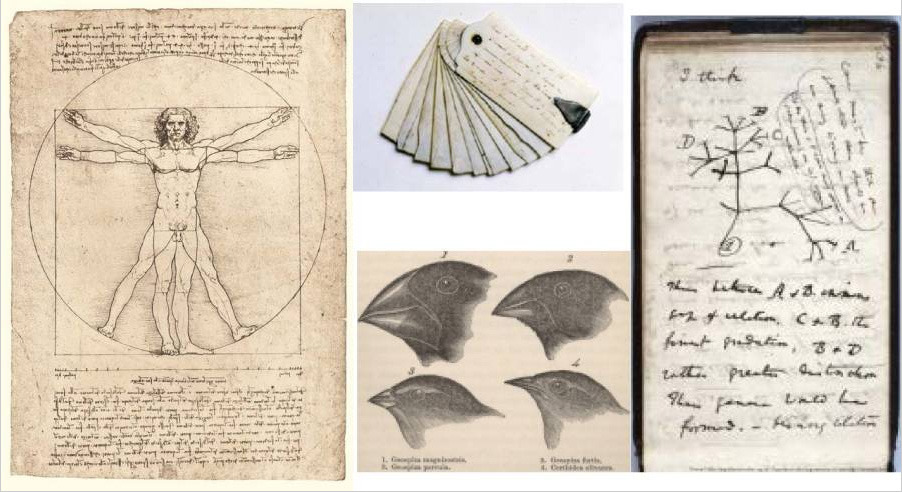

Laboratory notebooks have been used for centuries to document and archive the thoughts and work of inventors, scientists, and engineers. Even before the invention of paper, Archimedes (circa 287 BC – 212 BC) made notes and drawings of his mathematical discoveries and mechanical inventions on parchment made from animal skins.[1] Leonardo da Vinci (1452–1519) encapsulated perhaps some of the best known early combinations of experimental documentary concepts when he put pen to paper to combine his creativity and artistry in a format that has endured well beyond his lifetime (see Fig. 1). He even employed a degree of data encryption in his mirror writing, to provide a measure of privacy.[2] Benjamin Franklin (1706–1790) and Thomas Jefferson (1743–1826) not only kept notebooks on their ideas and interests but they utilized a portable version of a memo pad made from thin ivory leaves, fastened together at one end so they could be fanned out for use.[3] These were re-writable; therefore, notes had to be ultimately transcribed to permanent notebooks for archival purposes, but the portability aspect was a key feature. Charles Darwin (1809–1882) is another familiar example of someone who combined artistry with documentation to provide compelling evidence that led to his theory of evolution.[4] During his long (1831–1836) voyage on the Beagle, he used 14 different notebooks on his extensive field excursions, with a separate notebook dedicated to each major location. Later, prolific inventors like Thomas Edison (1847–1931) made extensive use of laboratory notebooks to document exploration into a wide variety of fields.[5] This was mainly to organize and document information to serve as a legal instrument for the development and protection of patents, so an audit trail was an important feature. But pen and paper is a static and limited medium. Enter the computer age and the internet where data, text, and images can be stored and transported as electrons and we have a new paradigm: the electronic laboratory notebook (ELN).

|

Notes

This presentation is faithful to the original, with only a few minor changes to presentation. In some cases important information was missing from the references, and that information was added. Direct citations of Wikipedia were replaced with a relevant citation from that Wikipedia article.

- ↑ Miller, Mary K. (March 2007). "Reading Between the Lines". Smithsonian Magazine. Smithsonian Institution. http://www.smithsonianmag.com/science-nature/reading-between-the-lines-148131057/. Retrieved 26 September 2016.

- ↑ Richter, Jean P. (1883). "The Notebooks of Leonardo Da Vinci". sacred-texts.com. http://www.sacred-texts.com/aor/dv/.

- ↑ "Thomas Jefferson: Life and Labor at Monticello". Library of Congress. 2015. http://www.loc.gov/exhibits/jefferson/jefflife.html.

- ↑ van Wyhe, John, ed. (2002). "Darwin's notebooks and reading lists". The Complete Work of Charles Darwin Online. http://darwin-online.org.uk/EditorialIntroductions/vanWyhe_notebooks.html.

- ↑ "Part I: Series Notes". Thomas A. Edison Papers Project. Rutgers School of Arts and Sciences. 2015. http://edison.rutgers.edu/sernote1.htm.