Journal:Critical analysis of the impact of AI on the patient–physician relationship: A multi-stakeholder qualitative study

| Full article title | Critical analysis of the impact of AI on the patient–physician relationship: A multi-stakeholder qualitative study |

|---|---|

| Journal | Digital Health |

| Author(s) | Čartolovni, Anto; Malešević, Anamaria; Poslon, Luka |

| Author affiliation(s) | Catholic University of Croatia |

| Primary contact | Email: anto dot cartolovni at unicath dot hr |

| Year published | 2023 |

| Volume and issue | 9 |

| Article # | 231220833 |

| DOI | 10.1177/20552076231220833 |

| ISSN | 2055-2076 |

| Distribution license | Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International |

| Website | https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/20552076231220833 |

| Download | https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/reader/10.1177/20552076231220833 (PDF) |

|

|

This article should be considered a work in progress and incomplete. Consider this article incomplete until this notice is removed. |

Abstract

Objective: This qualitative study aims to present the aspirations, expectations, and critical analysis of the potential for artificial intelligence (AI) to transform the patient–physician relationship, according to multi-stakeholder insight.

Methods: This study was conducted from June to December 2021, using an anticipatory ethics approach and sociology of expectations as the theoretical frameworks. It focused mainly on three groups of stakeholders, namely physicians (n = 12), patients (n = 15), and healthcare managers (n = 11), all of whom are directly related to the adoption of AI in medicine (n = 38).

Results: In this study, interviews were conducted with 40% of the patients in the sample (15/38), as well as 31% of the physicians (12/38) and 29% of health managers in the sample (11/38). The findings highlight the following: (1) the impact of AI on fundamental aspects of the patient–physician relationship and the underlying importance of a synergistic relationship between the physician and AI; (2) the potential for AI to alleviate workload and reduce administrative burden by saving time and putting the patient at the center of the caring process; and (3) the potential risk to the holistic approach by neglecting humanness in healthcare.

Conclusions: This multi-stakeholder qualitative study, which focused on the micro-level of healthcare decision-making, sheds new light on the impact of AI on healthcare and the potential transformation of the patient–physician relationship. The results of the current study highlight the need to adopt a critical awareness approach to the implementation of AI in healthcare by applying critical thinking and reasoning. It is important not to rely solely upon the recommendations of AI while neglecting clinical reasoning and physicians’ knowledge of best clinical practices. Instead, it is vital that the core values of the existing patient–physician relationship—such as trust and honesty, conveyed through open and sincere communication—are preserved.

Keywords: artificial intelligence, patient-physician relationship, ethics, bioethics, qualitative research, multi-stakeholder approach

Introduction

Recent developments in large language models (LLM) have attracted public attention in regard to artificial intelligence (AI) development, raising many hopes among the wider public as well as healthcare professionals. After ChatGPT was launched in November 2022, producing human-like responses, it reached 100 million users in the following two months. [1] Many suggestions for its potential applications in healthcare have appeared on social media. These have ranged from using AI to write outpatient clinic letters to insurance companies, thereby saving time for the practicing physician, to offering advice to physicians on how to diagnose a patient. [2] Such an AI-enabled chatbot-based symptom checker can be used as a self-triaging and patient monitoring tool, or AI can be used for translating and explaining medical notes or making diagnoses in a patient-friendly way. [3] Therefore, the introduction of ChatGPT represented a potential benefit not only for healthcare professionals but also for patients themselves, particularly with the improved version of GPT-4. In addition to ChatGPT, various other LLMs are at different stages of development, for example, BioGPT (Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Boston, MA, USA), LaMDA (Google, Mountainview, CA, USA), Sparrow (Deepmind AI, London, UK), Pangu Alpha (Huawei, Shenzen, China), OPT-IML (Meta, Menlo Park, CA, USA), and Megatron Turing MLG (Nvidia, Santa Clara, CA, USA). [4]

However, despite the wealth of potential applications for LLM, including cost-saving and time-saving benefits that can be used to increase productivity, there has been widespread acknowledgement that it must be used wisely. [3] Therefore, the critical awareness approach mostly relates to underlying ethical issues such as transparency, accountability, and fairness. [5] Critical thinking is essential for physicians to avoid blindly relying only on the recommendations of AI algorithms, without applying clinical reasoning or reviewing current best practices, which could lead to compromising the ethical principles of beneficence and non-maleficence. [6] Moreover, when using LLM in the healthcare context, the provision of sensitive health information by feeding up the algorithmic black box might be met with a lack of transparency in terms of the ways in which the commercial companies will use or store such information. In other words, such information might be made available to company employees or potential hackers. [4] In addition, from a public health perspective, using ChatGPT could potentially lead to an "AI-driven infodemic," producing a vast amount of scientific articles, fake news, and misinformation. [5] Therefore, all of these challenges [7] necessitate further regulation of LLM in healthcare in order to minimize the potential harms and foster trust in AI among patients and healthcare providers. [1]

Interestingly, healthcare professionals have demonstrated openness and readiness to adopt generative AI, mostly because they are excessively burdened by administrative tasks [8] and are desperately seeking a practical solution. Several medical specializations have been identified as benefiting from the use of medical AI, including general practitioners [9], nephrologists [10], nuclear medicine practitioners [11], and pathologists [12], with the technology reportedly having a direct impact on physicians’ roles, responsibilities, and competencies. [12–14] Although the above-mentioned potential has been recognized, various studies have noted that the implementation of medical AI would bring about certain challenges [15] and barriers [16], such as physicians’ trust in the AI, user-friendliness [17], or tensions between the human-centric model and technology-centric model, that is, upskilling and deskilling [18], which will further impact on the (non-)acceptance of AI-based tools. [17]

Aims

This study seeks to present the aspirations, fears, expectations, and critical analysis of the ability of AI to transform healthcare. Therefore, this qualitative study aims to provide multi-stakeholder insights, with a particular focus on the perspectives of patients, healthcare professionals, and managers regarding the current state of healthcare, the ways in which AI should be implemented, the expectations of AI, the synergistic effect between physicians and AI, and its impact on the patient–physician relationship. These results will provide some clarification regarding questions that have been raised about openness towards embracing AI, and critical awareness of AI's potential limitations in clinical practice.

Methods

This study was conducted from June to December 2021 as a multi-stakeholder (n = 75) qualitative study. It employs an anticipatory ethics approach, an innovative form of ethical reasoning that is applied to the analysis of potential mid-term to long-term implications and outcomes of technological innovation [19], and sociology of expectations, focusing on the role of expectations in shaping scientific and technological change. [20,21] These are the theoretical frameworks underpinning the design of the qualitative study, in which the questions were followed by two scenarios set in 2030 and 2023 to stimulate discussions. Although both referred to the digital health context, the first scenario focused on the use of an AI-based virtual assistant, while the second focused on self-monitoring devices. This article focuses only on the first scenario (see Appendix I) as it was embedded in the clinical setting and depicts the future care provision and transformation of healthcare. The study follows the consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ) guidelines [22] (see Appendix II). Furthermore, it was approved by the Catholic University of Croatia Ethics Committee n. 498-03-01-04/2-19-02.

Participants and recruitment

A purposeful random sampling method was employed. The inclusion criteria included that they belonged to specific key stakeholder groups (physicians, patients, or hospital managers), while people who were under 18 years of age or who did not fall into any of the specified key stakeholder groups were excluded. The participants were recruited using the snowballing technique until data saturation was reached, respecting and ensuring data heterogeneity and aiming for maximum variation in variables such as stakeholder category, age, gender, and location. Participants (n = 75) were identified as stakeholders in the healthcare context: patients, physicians, IT engineers, jurists, hospital managers, and policymakers (Figure 1). Initially, an email was sent to invite participation in the research. Some of the invitees did not respond to the email, though no one provided reasons for declining. Of those who agreed to participate, some participants opted to postpone the interviews due to other commitments, and some were ultimately not conducted.

|

Considering the context, with the recent introduction of ChatGPT and outlined aim, it was decided to focus mainly on three groups that were directly affected by the adoption of AI in medicine (n = 38), which were physicians (n = 12), patients (n = 15), and healthcare managers (n = 11). All participation was voluntary and, prior to the interview, participants received all of the information they needed to provide informed consent.

Data collection and analysis

Semi-structured interviews were conducted both in-person (at locations convenient for the participants or at the research group's work office) and online, using the Zoom platform, by researchers experienced in qualitative research. Only the participant and the researcher attended the interviews. The initial interview guide was based on the authors’ previous desk research on recognized ethical, legal, and social issues in the development and deployment of AI in medicine. [23] It was inspired by similar studies [24–26] and was pilot-tested on a group of 23 stakeholders. Later, the interview guide was adapted as the study continued to take account of emerging themes until data saturation was reached. All interviews were recorded using a portable audio recorder and later transcribed; the average length of interviews was 47 minutes. Transcripts were not provided to participants for comments or corrections. The transcribed interviews were entered into the NVivo qualitative data analysis software. Researchers familiarized themselves with the material by reading the transcripts and taking notes to gain deeper insights into the data. Next, a thematic analysis was conducted. [27] Following that, an open coding process was initiated for the interviews (n = 11). Based on the initial codes, the researchers agreed on thematic categories [28], leading to the development of the final codebook, which was then used to code the remaining interviews. Finally, the researchers combined and discussed themes for comparison and reached a consensus on how to define and use them. All interviews were analyzed in the original language (Croatian), and the quotes presented in this article have been translated into English.

Results

Participant demographics

This study focuses on 38 conducted interviews with patients (comprising 40% of the sample; 15/38), followed by physicians (31% of the sample; 12/38), and health managers (29% of the sample; 11/38). In terms of gender, 53% of the participants were female (20/38), while 47% (18/38) were male. The participants’ ages ranged from the 18 to 24 age group to the 65 and older category. Regarding the geographical distribution, most respondents 74% (28/38) hailed from urban centers, and nine participants, representing 23% of respondents (9/38), were from the urban periphery, whereas one participant resided in a rural periphery (Table 1). A minority of patients (33%; 5/15) regularly used technology for health monitoring, such as applications and smart devices (e.g., smartwatches), in their daily routines.

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Thematic analysis

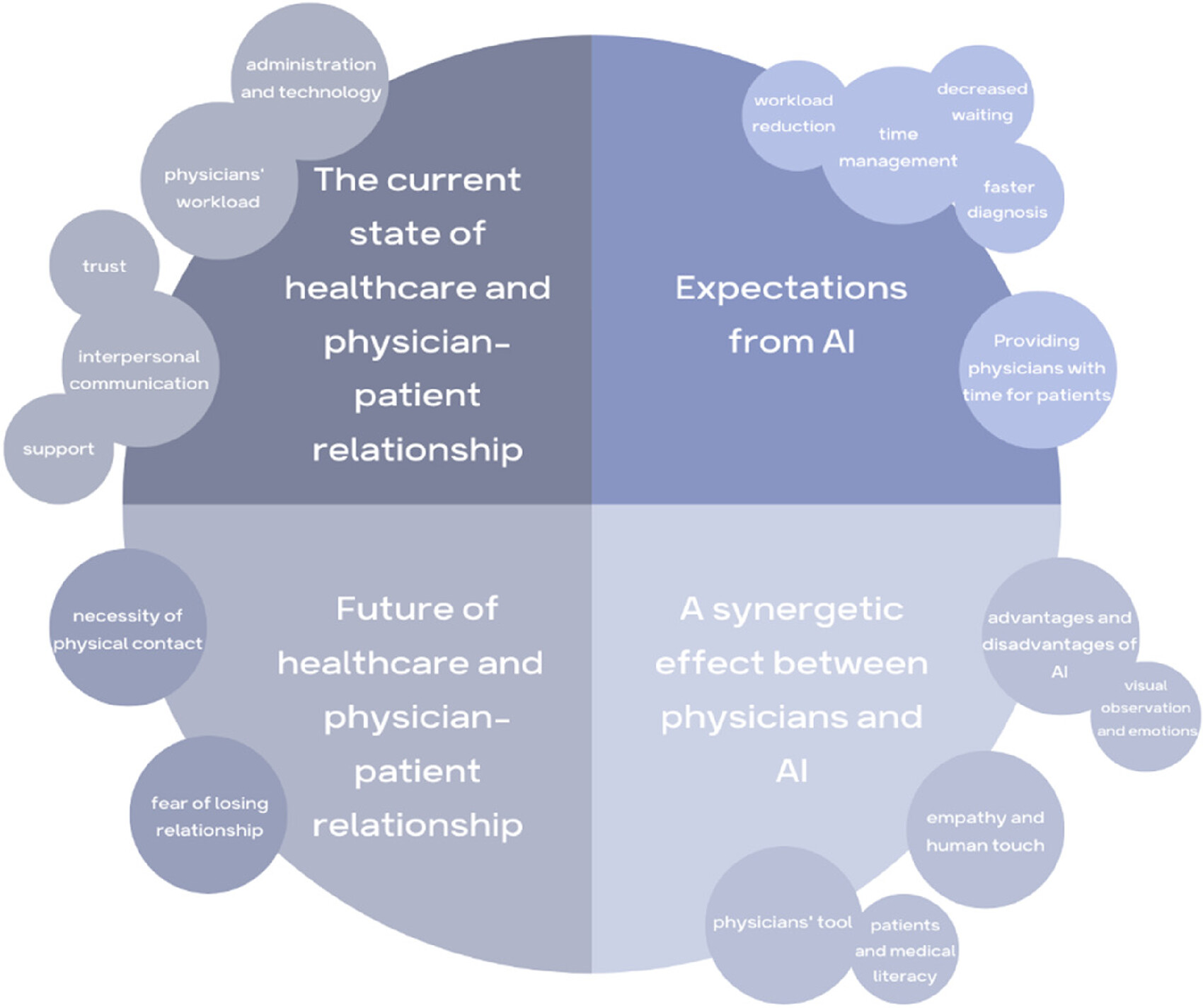

Four themes and subthemes (Figure 2) were identified: (1) the current state of healthcare and the patient–physician relationship; (2) expectations of AI; (3) a synergetic effect between physicians and AI; and (4) the future of healthcare and the patient–physician relationship.

|

The current state of healthcare and the patient–physician relationship

Research participants reflected on the current state of healthcare, discussing both positive and negative aspects. Their responses encompassed a wide range of topics related to healthcare, including health policies, infrastructure, physicians’ qualifications, patients’ medical literacy, weak hospital management, and financial losses. While each of these themes is intriguing for analysis, this section will focus on the current state of the patient–physician relationship, and specifically those aspects highlighted by the participants as being the essential, positive, or negative aspects of this relationship.

Many participants emphasized trust, honesty, and effective interpersonal communication as a fundamental aspect of the patient–physician relationship. Patients stressed the importance of being heard by their physicians and actively engaging in a shared decision-making process.

I think the most important thing for me is that we communicate about everything. To talk. To trust what he tells me. (Patient 5)

It's important that he[a] listens to me and doesn't jump to conclusions before I fully explain the issue. (Patient 9)

It is crucial that he listen to me and that I listen to him. That's really the most important thing because if he does not listen to me, if it only gets heard in one ear, coming here is a waste of time. (Patient 12)

Physicians also emphasized the importance of patients having trust in them, identifying openness and honesty as directly enabling the identification of the fastest and optimal treatment approach. Furthermore, they highlighted the significance of patients’ ability to articulate their condition effectively, enabling them to convey their symptoms clearly to the physician.

When they have trust in me, it becomes much easier for me to treat them. (Physician 3)

I have always strived, both in direct and indirect interactions at work, to listen to the patient, guide them, and provide advice in good faith, with the simple aim of resolving any issues. (Physician 4)

The most crucial aspect is establishing easy communication and trust in what we do. (Physician 12)

Actually, it's always about honesty. Knowing that, when patients speak, they tell the exact truth and don't deceive. That's an essential factor for me. Another important factor is the patient's capacity to communicate clearly. To correctly interpret their symptoms and condition of health. To convey a comprehensive picture to me. (Physician 11)

Some physicians emphasized that patients often come to them specifically to have a conversation. In other words, patients sometimes approach physicians not only for health issues but also for support and simply to be heard.

Many people come to the physician just to vent. They come to vent, and then we find some psychological component in a good percentage of them. I believe it's important for them to sit down with the physician, have a chat. (Physician 11)

Some patients reported that they have developed a friendly relationship with their physician due to long-term treatment.

The friendship that is built over the years is essential because I have been with this physician for twenty years, and I simply feel like… When I come to her, it's like talking to a friend – we chat a little, laugh, and then I start talking about my [health] problems. (Patient 11)

A friendly patient–physician relationship must be developed. (Patient 5)

Patients also expressed dissatisfaction that they sometimes do not receive enough care and attention from physicians. However, they were aware that the reason for this is often the physicians’ overwhelming workload and the limited time they have available.

It feels selfish to ask because I know they have a lot of work to do, but I don't like being just a number and a piece of paper in a drawer. (Patient 10)

You feel like they want to get rid of you. To get it done as quickly as possible, and that's it. (Patient 1)

Some participants pointed out that the paperwork is a problem. According to them, physicians are more focused on paperwork than on the individuals sitting in front of them.

I'd prefer if the physician didn't just look at the papers but lifted their head, talked to me, gave me a look, and conducted an examination if needed, which is equally important, because lately, it often seems to be reduced to just paperwork. (Patient 15)

Physicians also expressed dissatisfaction with the fact that a part of their consultation time with patients is spent on tasks that could be done differently or replaced by other methods.

Suppose I spend time measuring their blood pressure at every consultation, explaining to them that I'm referring them for certain tests, and prescribing medications every time. In that case, I have less time for purposeful [laughs] procedures that could really impact treatment outcomes, right? (Physician 9)

One aspect that physicians highlighted as being time-consuming was the administrative tasks undertaken during patient consultations. Similarly, manual data collection and entering data into the system often means the physician is spending the meeting time looking at a screen, having limited actual contact with the patient who is there.

Because, honestly, all that typing, printing, and confirming of test results and such, I waste a lot of time on it, and the actual examination of the patient and talking to them, I believe, should be retained, but in a way that avoids the need for me to look at the screen constantly. Personally, when I gather data, sometimes I forget that, while I'm typing and looking at the screen, I'm not really looking at the patient themselves, and I end up missing information I could gather just by observing them. (Physician 3)

Today, they are mostly on the computer, and they have to type everything, so they have very little time to dedicate to us patients. (Patient 1)

Somehow, since computers were introduced in healthcare, a visit to one physician, a neurologist, for example, would be like this: I spent 5 minutes with him. Out of those 5 minutes, he would talk to me for a whole minute, and then spend 4 minutes typing on his computer. (Patient 13)I want to be polite, look at him, and talk to him, but on the other hand, you see this “click, click”, and if I don't click, I can't proceed. And then he says, “Why are you constantly looking at that [computer]?” – I mean, it's impolite, right? But I can't continue working because I have to type this and move on to the next… (Hospital manager 4)

Furthermore, hospital manager 4 also expressed concern about the current state of healthcare by pointing out that physicians have already become too focused on technology, neglecting personal contact with patients.

We forget that psychosomatics is 80–90%. The placebo effect, communication, positive thinking, and interaction are crucial. It's highly important, but we have neglected it and focused too much on technology. (Hospital manager 4)

Hospital managers felt that this issue might particularly affect young physicians who have not yet developed the skills that older physicians possess, due to their limited experience of patient interaction, and were further concerned that such physicians may not develop these skills because of excessive reliance on technology. This primarily pertains to patient communication, observation, and support.

For instance, when the electricity goes out, younger physicians will call me to ask whether they should examine patients or wait for the computer to start up. (Hospital manager 9)

Participants pointed out that communication and trust between patients and physicians are the keys to a good relationship. On the other hand, they reported often feeling that relationship difficulties are due to insufficient time caused by administrative tasks and the workload burden on physicians. Interestingly, existing non-AI-based technology, to the extent that it is now present, was perceived as being a negative factor and an obstacle to direct interaction between physicians and patients.

Expectations of AI

Footnotes

- ↑ In Croatian, the noun physician (liječnik) is masculine; therefore, the patient refers to the physician as a male.

References

Notes

This presentation is faithful to the original, with only a few minor changes to presentation, grammar, and punctuation. In some cases important information was missing from the references, and that information was added. The original lists references in alphabetical order; this version lists them in order of appearance, by design.