User:Shawndouglas/sandbox/sublevel5

The physician office laboratory (POL) is a clinical laboratory that is physician-, partnership-, or group-maintained, with the goal of diagnosing, preventing, and/or treating a disease or impairment in a patient as part of a physician practice. Definitions vary from state to state, but this is a solid enough definition. Slightly more than 40 percent of all clinical laboratories in the U.S. are POLs according to Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services statistics from March 2022.[1] This chapter addresses the clinical laboratory testing environment, with a focus on these POLs.

2. The Clinical Environment

This is where something ...

2.1 The POL as a clinical laboratory

The physician office laboratory (POL) is a type of clinical laboratory located in an ambulatory or outpatient care setting, usually in the physician office. A clinical laboratory specializes in testing specimens from human patients to assist with the diagnosis, treatment, or monitoring of a patient condition. That testing generally depends on one or more of three common methodologies to meet those goals: comparing the current value of a tested substance to a reference value, examining a specimen with microscopy, and/or detecting the presence of infection-causing pathogens.[2] The success of these methodologies is largely dependent upon the actions of laboratory directors, supervisors, pathologists, cytotechnologists, histotechnologists, and clinical laboratory assistants who perform and interpret analyses of patient specimens using one or more techniques.[3] Those methodologies and techniques also require a wide variety of instruments and equipment. A histotechnologist will require a microtome to prepare a specimen for an anatomical pathology examination, and blood chemistry analyses depend on sample tubes, centrifuges, and blood analyzers. More advanced clinical laboratories performing molecular diagnostics techniques will use specialty tools like fluorescence microscopes and spectrometers. And all that equipment must meet manufacturing, testing, and calibration standards to ensure the utmost accuracy of tests.[4]

However, the clinical environment of the POL is somewhat different than your average reference or diagnostic lab that receives, processes, and reports on specimens en masse. The POL is typically a smaller operation, performing simple laboratory testing that can produce useful diagnostic data cheaply and rapidly. Rather than performing advanced pathology procedures that require specific equipment and expertise, the POL typically focuses on blood chemistry, urinalysis, and other testing domains that don't require significant resources and provide rapid results. This can be seen in Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services statistics reported in March 2022 that show 68.9 percent of POLs in the U.S. are certified to provide CLIA-waived tests[5], "simple tests with a low risk for an incorrect result."[6] These "simple tests" don't require advanced equipment and highly-trained physicians. Urinalysis reagent strips, influenza nasal swabs, and whole blood mononucleosis kits are all CLIA-waived testing devices that can be used by well-trained phlebotomists, nurses, or laboratory assistants.[7] Some POLs opt to provide more advanced testing services, however, with 17.3 percent of all POLs holding provider performed microscopy (PPM) certificates to perform moderate-level CLIA testing.[5] This allows POLs to perform moderate complexity tests like urine sediment analysis and the determination of "the presence or absence of bacteria, fungi, parasites, or cellular elements" in a specimen.[8] However, the majority of POLs remain smaller and simpler than their diagnostic lab counterparts.

2.2 Good laboratory practices

As previously stated, the ultimate goal of the clinical laboratory—and by extension, the POL—is to test specimens from human patients to assist with the diagnosis, treatment, or monitoring of a patient condition. This, of course, requires accurate results to ensure the best result. In the 1970s, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration noted non-clinical laboratories in many cases conceived experiments poorly, failed to inform laboratory personnel of protocol, and didn't regard strict laboratory procedure to be necessary. This brought about the Good Laboratory Practice regulations in November 1976.[9][10] Clinical laboratories were not left out of this recognition of the need for improvements, however. Though the Clinical Laboratories Improvement Act of 1967 brought about some reforms to laboratory practices[11], the act wasn't doing enough by the mid-1980s. The regulations were revised and put into effect on October 31, 1988 as the Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments of 1988.[12] Known as "CLIA," the regulations have helped shape the policy and procedure of clinical laboratories of all types, including how training and experience is gauged and documented, reagents are prepared, and quality control is approached.

Today in the U.S., like any other clinical lab, physician office laboratories must follow good laboratory practices to ensure the best outcomes for its associated patients. These practices must be engaged in at every stage of the laboratory testing process. During the initial test ordering process, for example, lab personnel must review orders for accuracy and seek verification from the physician if there are any questions. Following order entry, staff should complete a requisition and explain all preparation procedures to the patient. When the patient arrives, staff should use appropriate procedures and containers to collect the specimen(s) from the patient. Processing of the specimen should include proper storage, preservation (if required), labeling, and transportation. The POL must run quality control tests prior to testing the patient sample to ensure instruments are properly calibrated and appropriate testing proficiency is met. After test completion, a laboratory report is printed and the physician notified. Patients should also be notified per the policy of the physician practice. Disposal of laboratory waste is also part of good laboratory practice, as is proper documentation in the patient record regarding testing and results.[2]

2.3 Laboratory safety

Like any other laboratory, safety in the clinical laboratory is of vital importance. Good safety practices ensure the specimen being tested does not get contaminated, and they also protect the person doing the testing from infection or other issues resulting from exposure.

Quality control guidelines and standards ensure procedures are followed and equipment is checked, lowering specimen contamination risk and improving the accuracy of test results. Laboratory safety guidelines assist professionals with managing risk from biohazards, chemical hazards, or physical hazards that may be present in the laboratory. The two U.S government agencies that primarily set safety guidelines are the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA). CDC training involves learning about the chain of infection and standard precautions for infection control, while OSHA biohazard training involves the blood borne pathogen standard (BBPS) as well as the exposure control plans and guidelines that promote staff health and safety. OSHA also requires training to deal with chemical hazards in the laboratory.[13][2]

Laboratories of any size must also deal with physical hazards such as obstructions, electrical equipment, fires, floods, and earthquakes. Preparing for these possible hazards in some cases can be as simple as ensuring a box is not placed where someone walking could trip over it. OSHA has numerous guidelines related to the physical hazard training, including how to conduct a fire drill. Other beneficial preparatory activities include organizing and documenting clearly labeled chemical inventories, providing clear access to material safety data sheets (MSDS), enacting a hazard communication program, and providing training on OSHA adherence protocols.[13][2]

The POL is not exempt from these quality control and safety considerations simply because it's smaller and less sophisticated, however. It may not have the chemical stocks and testing hazards of a large diagnostic lab, but specimens must still be kept uncontaminated, and procedures for using even the simplest of CLIA-waived test devices must be followed. Biohazards are still generated and must be treated appropriately using work-practice controls, personal protective equipment, and engineering controls. This includes handling bleach (sodium hypochlorite), one of the most prevalent chemicals in labs[14], which must still be handled properly to ensure human safety and equipment longevity.[13][2]

2.4 Regulatory compliance: HIPAA and PPACA

Clinical laboratories must comply with the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996 (HIPAA). Among HIPAAs many goals is the desire to improve privacy and security protections for an individual's personal and identifying health information. As such, laboratories are required to implement measures that prevent unauthorized disclosure of and access to a patient's protected health information (PHI) in the laboratory. In the original implementation of HIPAA, this meant that laboratory staff were discouraged from giving laboratory test results to a patient without physician permission.[2] However, in February 2014, the Department of Health and Human Services wanted to encourage patients to take a more proactive approach to their own health care by giving them a mechanism to learn more about their own health. The HHS put into place an amendment to CLIA that became effective in April 2014, allowing patients to request laboratory results directly from a laboratory. Under the change, laboratories (including POLs) were required to give patients their laboratory results within 30 days of a written request by the patient or authorized agent, while still maintaining safeguards related to patient data and other sections of HIPAA.[15] This of course applies to the POL and their associated physician offices, which remain the second-most common violator of HIPAA privacy regulations.[16]

Another federal statute that impacts laboratory testing is the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (PPACA), signed in 2010 by President Barack Obama. When enacted, this law cut fees paid for laboratory testing and established accountable care organizations (ACOs). Both the cuts to the Medicare Clinical Laboratory Fee Schedule and the creation of ACOs initially posed challenges to the laboratory—especially in the physician office—as economic concerns were expected to cause a laboratory to no longer have incentive to offer some forms of testing.[17] However, the PPACA brought with it a beneficial transition from an incentivized volumetric approach to clinical testing (fee for service) to a preventative approach focused on quality patient outcomes (value-based service).[18] This healthcare outcome approach matched will with the growing demand for point-of-care testing (POCT), which "promotes these goals with rapid test results that providers can use to immediately inform patients of their condition or progress, and modify their treatment on-site."[19] And while POCT—particularly CLIA-waived testing—can happen in many clinical labs, from the hospital to the urgent care clinic, it has become a significant source of testing for the POL.[20]

2.5 Regulatory compliance: CLIA

In 1988, CLIA was passed as an amendment to the original 1967 legislature.[12] CLIA attempts to ensure the accuracy, reliability, and timeliness of test results regardless of where the test was performed. As part of this process, seven different criteria are used to gauge and assign one of three complexity levels to laboratory devices, assays, and examinations: high, moderate, and waived.[6][21] Clinical laboratories handling specimens originating from the U.S. and its territories must apply for a CLIA certificate that is appropriate for the type of testing it performs.

The POL largely conducts CLIA-waived tests, with 68.9 percent of all POLs in the U.S. running on a CLIA certificate of waiver as of March 2022.[5] These tests are recognized as simple to perform with a low risk of erroneous results and include among others urinalysis for pregnancy and drugs of abuse, blood glucose and cholesterol tests, and fertility analysis. Despite the simplicity of a waived test, it "needs to be performed correctly, by trained personnel and in an environment where good laboratory practices are followed."[22] As such, CMS provided additional enforcement of labs with CLIA certificates of waiver in the 2010s, conducting on-site visits to approximately two percent of such labs to verify quality testing, regulatory compliance, and test appropriateness.[23]

CLIA-waived testing is not the only testing that goes on at a POL. In some cases, a POL may also offer moderate-level provider performed microscopy (PPM) testing (17.3 percent of all POLs as of March 2022[5]), depending on the office specialty.[2] To perform this type of testing in addition to waived testing, a PPM certificate is required.

For POLs exclusively conducting waived testing, anyone can be the laboratory director; however, some states have different requirements, so it is important the POL checks with their local regulatory body when hiring staff for the laboratory. POLs that also incorporate PPM testing have different requirements for directors, who "must meet specific education, training and experience under subpart M of the CLIA requirements."[24]

2.6 Point-of-care testing

The College of American Pathologists (CAP) defines POCT as "testing that is performed near or at the site of a patient with the result leading to a possible change in the care of the patient."[25] Historically this sort of testing was mundane due to the nature of the available methods; however, today these tests have advanced to include even limited forms of molecular diagnostics testing.[26] Like waived CLIA tests, POCT can also be performed by laboratory personnel. However, both personnel and patients (those who use testing devices at home) must be trained on how to use POCT devices in order to get the most accurate results.[27][28]

Some POCT devices are gradually allowing the patient to send data from their instruments—or even their mobile phones—directly to the physician office. However, this has historically not always a straightforward procedure. As the CAP noted in 2013 concerning POCT, "interoperability should be developed or expanded ... to provide better oversight and incorporation of results into the electronic medical record."[29] Multi-stage efforts towards "Meaningful Use" of electronic health records (EHRs) that are able to accept patient-generated data went into effect in the early to mid-2010s, followed by other pushes towards integrating POCT results with a wide variety of informatics systems.[30][31] However, interoperability and meaningful use of POCT data and EHRs still has work to do. As Labcorp's strategic director of clinical technology Adam Plotts notes, "[t]he main challenge is the way technology brings outside patient data into the provider's workflow."[32] During the COVID-19 pandemic, this has extended to at-home testing and the reporting of results over a mobile device.[33] However, from the perspective of the POL, these same at-home test kits can be used in the POL, and as long as results get properly documented—preferably in the patient's EHR record—POCT provides a better chance at timely patient outcomes.

2.7 Provider-performed microscopy testing

CLIA has approved some tests for the provider performed microscopy (PPM) level, a subcategory of the moderate complexity level. These tests must be of moderate complexity and require a microscope as the primary analysis tool, and they must be performed by a qualified physician or nurse practitioner in a set period of time, with limited handling of the specimen for the utmost accuracy.[34] Eligibility of PPM tests is determined by CMS, and those tests include wet mounted tissue examinations, semen analysis, certain mucous and nasal smears, and certain urinalyses.[35] (For the full list, consult the CMS-updated PDF file.)

These individual tests are useful to many POLs, though they have their own procedures and require the ability to focus and maintain the microscope at optimal performance level. Part of doing so is learning the structures of the microscope and how to use it. Since these procedures are performed by physicians or mid-level practitioners, the provider should be well trained in how to do this. They should be able to identify the parts of the microscope and understand how the lenses work. Knowledge of proper slide preparation is also vital, as improperly prepared slides can ruin an otherwise correctly performed PPMT procedure. In addition to an appropriate microscope, PPMT procedures require several other items, including immersion oil, lens paper, and tissue (lint free, soft).[2] Finally, though PPMT isn't regulated, the provider and laboratory personnel should carefully document quality assurance procedures for PPMT at regular intervals.[34] As noted previously, POLs that incorporate PPM testing have different requirements for laboratory directors than CLIA-waived labs, requiring a higher level of documented training and competence.[24]

2.8 CLIA market and industry trends

2.8.1 Clinical laboratory testing trends

With over 13 billion laboratory tests performed in the United States every year, laboratory testing is the highest volume medical activity in the country.[36][37] Laboratory testing influences approximately two-thirds of all medical decisions, and this testing often directs far more expensive care.[36] As these trends continue, the laboratory will likely become a coordinator for the patient and care team. The laboratory will serve as a facilitator for the patient and clinicians alike to receive not only test results but also education about those results. The laboratory will also assist the clinical team with test utilization, reporting those results into the EHR as well as maintaining them.[36]

Laboratory testing is in an upward trend, as seen with the growth of point-of-care testing and the patient-centered medical home (PCMH). Given the popularity of consumer products that track healthcare data, this trend should continue for years to come. One example of this is VeinViewer, which assists the phlebotomist with the location of veins and eliminates the painful process of sticking a patient more than once in an attempt to draw blood.[38] Other technologies are driving trends in this area, including in the testing domain, where for example Healthy.io (which acquired Scanadu/inui Health in 2020) offers a urinalysis strip than can be analyzed with a mobile app.[39][40]

2.8.2 POL testing trends

The third installment of research firm Kalorama Information's Physician Office Laboratory Markets reported the number of POLs performing CLIA-waived in vitro diagnostic (IVD) testing increased an average annual rate of 3.8 percent from 2005 to 2013, though "the number of POLs conducting moderate- and high-complexity testing under CLIA compliance or accreditation decreased by an annual average rate of 0.8 percent."[41] In mid- to late 2014, Kalorama estimated that POLs were conducting nine percent of all clinical IVD testing in the United States, also noting that "[n]ine out of the ten most-performed POL tests in the United States are CLIA-waived."[42]

As for what's being tested, the report noted that "[i]n the past five years, the most performed POL tests have changed little with the exception of some recently CLIA-waived infectious disease tests and vitamin D testing."[41] The study also found that many of the CLIA waivers granted in 2014 have been for tests in "highly competitive, established POL segments, such as drugs-of-abuse testing, routine clinical chemistries, urinalysis, hormone tests (including pregnancy), and dipstick urinalysis."[43] Many of those IVD tests were likely waived by regulation or cleared for home or over-the-counter use; however, a few of those tests had to go through a more rigorous process to become CLIA-waived.

Kalorama Information hasn't released a POL-specific report since 2014, but some information can be gleaned from other sources. In 2020, market research from Health Industry Distributors Association (HIDA) reported that POCT was outpacing overall diagnostic markets, and that molecular diagnostics is one of the fasted growing lab subspecialties.[44] This matches Thill's 2020 assessment that molecular diagnostics testing is becoming more readily available to the POL.[26] Thill also highlights the potential for PPM testing to make a comeback in the POL after nearly a decade of the percentage of labs performing PPM and other forms of moderate testing dropping. Writing for Repertoire magazine, Thill envisions those numbers slowly increasing again in the future, particularly given the rapid technological developments in molecular diagnostics testing, shifting some CLIA moderate molecular tests to waived, and other high-complexity molecular test to moderate. POLs wanting to perform more COVID-19 testing for their patients may also be a motivating factor to move up to CLIA moderate testing. This move to moderate may also be compelling to larger physician practices of five or more physicians wanting to conduct a higher throughput of both waived and moderate testing.[26]

2.8.3 Addition of the Dual 510(k) and CLIA Waiver by Application process

Originally an IVD test product not CLIA-waived by regulation or not cleared for home or over-the-counter use — even if it had clear advantages as a CLIA-waived product — would have to first be taken through the FDA 510(k) premarketing submission process which would then classify it as moderate or high complexity.[45] Then, if the product was viable as a moderate complexity device, the manufacturer would try to market and make money on their product and then go through the CLIA Waiver by Application process if they thought there were clear benefits and eligibility for CLIA-waived product status. This process would work for many manufacturers but frustrate a few (as of 2014, only 10 to 12 CLIA Waiver by Application requests were arriving to the FDA each year) who deemed their product non-viable to market unless it were CLIA-waived.[46]

Initially driven by the Medical Device User Fee Amendments of 2012 (MDUFA III) — an FDA attempt "to increase the efficiency of regulatory processes in order to reduce the time it takes to bring safe and effective medical devices to the U.S. market"[47] — the FDA sought to overhaul its Administrative Procedures for CLIA Categorization guidance documents, tracking mechanisms, and public CLIA database to improve the IVD and medical equipment regulation process. Among these changes, effective March 21, 2014, was the addition of the Dual 510(k) and CLIA Waiver by Application process, specifically for "that small subset of products that are not really viable if they are not waived."[46][48][49] The process is specific, requiring a pre-submission to receive FDA feedback first and be cleared for the Dual strategy. If approved, both the 510(k) and the CLIA Waiver by Application can be submitted at the same time.[46][45][50] On December 17, 2014, rapid diagnostic manufacturer Quidel Corporation announced its Sofia Strep A+ Fluorescent Immunoassay became the first product to be approved through the Dual program[51], opening a potential gateway for other rapid diagnostic companies to fast-track their product through FDA and CLIA waiver approval. By 2020, more finalized reforms to the Dual program clarified the submission process, with the FDA stating, "Use of the dual 510(k) and CLIA waiver by application pathway is optional; however, FDA believes this pathway is in many instances the least burdensome and fastest approach for manufacturers to obtain a CLIA waiver and at the same time as 510(k) clearance."[52]

2.8.4 More sophisticated CLIA-waived tests appear

More sophisticated tests eligible for labs with a certificate of waiver are appearing as of late, further increasing same-day testing opportunities in POLs. The first ever waived rapid screening test for syphilis was approved in the United States in December 2014, allowing physicians to make a preliminary diagnosis in as soon as 12 minutes. The product came about with the recognition of a the increasing number of primary and secondary syphilis cases in the U.S., nearly 55,000 new cases a year.[53] HIV testing is another growing segment of POL activities. Nearly four percent of all approved CLIA-waived tests are HIV tests, and of labs that offer CLIA-waived testing in general, 36 percent of them include at least one CLIA-waived HIV test.[54] The demand for more accurate and timely test results has driven companies like Trinity Biotech to create more flexible options; in November 2014 the company announced its Uni-Gold Recombigen HIV test "for the detection of antibodies to HIV in human serum, plasma, venous, and finger stick whole blood" was approved for CLIA-waived status, making it at the time the only rapid HIV test to be approved for all sample types.[55]

Several POCT companies have stepped up their CLIA-waived efforts recently, including Alere, Inc. and Cepheid, Inc. In an April 2015 interview with GenomeWeb, Cepheid chairman and CEO John Bishop stated the company would be "adding a sales force specifically for the CLIA market in early May" with expectations that the "market is actually going to step up overall test volumes as you move more broadly-disseminated."[56] Alere has been doing the same, though both companies are arguably heading up the charge towards a new potential trend in the CLIA-waived testing market: molecular and nucleic acid-based testing.

"I think the molecular tests are going to grab market share very rapidly ... and that's going to get even more emphasized with all of the programs now on antibiotic stewardship and more diagnostically directed use of therapeutics."[56] - John Bishop, Cepheid, Inc. chairman and CEO

"[W]e look forward to kind of changing the concept in the marketplace, [and showing] that you can get a highly sensitive, molecular result in minutes."[57] - K.C. McGrath, Alere, Inc. respiratory product manager

"We expect many other simple and accurate tests using nucleic acid-based technology to be developed in the near future. Once cleared by FDA, such tests can allow health care professionals to receive test results more quickly to inform further diagnostic and treatment decisions."[58] - Alberto Gutierrez, FDA director of the Office of In Vitro Diagnostics and Radiological Health

"I think traditional [polymerase chain reaction] assays will get better, faster, their boxes will get smaller, and you'll start to see a lot more point-of-care approved tests."[59] - Christine Ginocchio, BioMérieux vice president of global microbiology affairs

Molecular diagnostic tests have long been the domain of the full-fledged laboratory, even as companies like Cepheid have made progress with sales of its molecular Flu Xpert test[56], rated by CLIA for moderate complexity labs.[60] With only roughly 30 percent of physicians offices running at moderate complexity[57], however, molecular testing has seemed largely out-of-reach for the POL. Yet in January 2015, Alere and the FDA announced that the i Influenza A & B test had become the first ever nucleic acid-based test to receive CLIA-waived status, meaning it could be offered in POLs with a certificate of waiver.[60][58] While it's not clear if molecular point-of-care and and POL-friendly tests will become more prevalent in the coming years, their benefit to the POL are becoming clearer. In the case of the i Influenza A & B test, diagnosing a patient with influenza on a same-day physician visit with easy-to-use molecular tech could potentially reduce antibiotic prescriptions, decrease infection rates, and improve outcomes through early detection.[58]

2.8.5 Other players in the CLIA market

Other entities are beginning to focus on the CLIA market as well. Take AmericanBio, a custom reagent manufacturer that announced in October 2014 that it was implementing a "CLIA Grade product line and CLIA Grade Custom Manufacturing Services," helping device manufacturers sort through "regulatory framework, validation needs, consistency, and quality driven metrics that will support their diagnostic tool," both traditional and molecular.[61] Additionally, seminars and webinars on getting medical devices CLIA-waived are appearing from market research companies like Research and Markets and government agencies like the National Institutes of Health.[62][63] And niche businesses like Precision for Medicine are popping up, offering specialty regulatory, device, and test development services for the CLIA market.[64]

2.8.6 Side-effects of cheap and easy testing

The CLIA market, however, is not without its warts. One of the potential side-effects of cheap and easy testing in the physician office is the occasional desire to monetize it, particularly when Medicare reimbursement for a particular set of tests is quite lucrative. While in the U.S. the profit-driven trend of health care has caused many to debate further changes, in truth physicians still must be concerned with at least meeting operating costs.[65] However, some physicians have been more opportunistic, particularly in the field of urine drug testing. A 2012 article in the Journal of Pain & Palliative Care Pharmacotherapy titled "Profit-Driven Drug Testing" showed urine drug screens for both waived and non-waived tests reimbursed by Medicare increased by 4,537 percent from 2000 to 2009. Even worse, "the total number of CLIA-waived drug tests (CPT Code 80101QW) paid for by Medicare and conducted at physicians’ offices increased approximately 3,172,910 percent; with 101 tests conducted in 2000 and 3,204,740 in 2009."[66] This sudden increase of reimbursements came in part because physicians could bill Medicare per panel, meaning an 11-panel urine drug screen could be billed 11 times. CMS amended their rules in 2010 to prevent this type of unintended billing behavior, making drug testing less lucrative in general, especially for the POL.[66]

Yet some labs with a CLIA certificate of compliance or accreditation to handle moderate to advanced tests would continue to skirt the issue by moving to advanced mass spectrometry urine drug tests (qualitative) due to Medicare guidelines that encourage doctors to test patients using pain medicines to ensure their proper usage. In late 2014, The Wall Street Journal reported that Medicare was spending $445 million on 22 advanced drugs-of-abuse tests in 2012, up by more than 1,400 percent from 2007. With separate tests for each substance screened, an incentive remained for laboratories and physicians to abuse moderate- to advanced-level urine drug testing.[67]

In The Practical Guide to the U.S. Physician Office Laboratory, four economic considerations were outlined: billing, insurance reimbursements, profitability/sustainability, and return on investment (ROI). In truth, all these considerations are closely related to each other, with the goal of at least meeting operating costs while providing quality care to patients. However, plenty of challenges must be navigated along the way, from meeting state and federal regulatory requirements to billing properly. For the POL in particular the practice must decide which tests to offer, finding balance between the most commonly ordered IVD tests — such as dipstick urinalysis, complete blood counts, and prothrombin time[68] — and those that will potentially see rapid revenue growth, including anemia tests, chronic inflammation tests, and the glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c) diabetic test.[69]

Another area POL operators must keep a close eye on is healthcare reform and reimbursement changes. The aforementioned 2010 CMS changes to urine drug screening compensation is one of many examples of how changing regulations and reimbursements can affect a POL's bottom line. The economics of data management, which tools to use and what data to save represent more considerations for the POL. "To improve clinical lab profitability in today's healthcare environment, it is essential for any practice to establish an ongoing process to produce data relevant to the management of its patient base," Medical Source, Inc. CEO Keith LaBonte said in 2011, also noting the importance of identifying relevant data and implementing effective processes for staff to collect and organize that data in data management systems.[70]

One recent issue that economically threatens the U.S. POL's bottom line relates to the Protecting Access to Medicare Act passed in April 2014. Though its original purpose was to delay Medicare payment cuts to physicians until March 2015, Medicare cuts targeting the clinical laboratory fee schedule starting on January 1, 2017 potentially threaten small laboratories, including POLs. CMS will be switching to market-based rate changes that researchers like Kalorama Information and organizations like the National Independent Laboratory Association (NILA) and the American Association for Clinical Chemistry (AACC) believe will adversely affect small laboratories.[71][41][72]

"Most concerning to NILA and the small labs it represents is the prospect of significant drops in prices to routine tests. Community and regional labs are especially sensitive to price pressures since they often serve vulnerable populations in niche markets that national labs do not, such as nursing homes or homebound patients who require phlebotomists to visit them. This leaves community labs little means to cope with declining reimbursement..."[72] - Bill Malone, Clinical Laboratory News managing editor

"[R]outine tests are likely to see the sharpest reductions in reimbursement with the enactment of the Act’s market-based pricing reform. Routine tests performed at the point of care (POC) or in a physician office laboratory (POL) are most vulnerable, as the cost of the test is often higher without the scale and efficiencies of a core lab environment. Non-automated tests or routine, waived manual tests with a unique code are unlikely to see price erosion on the scale of those largely performed on automated instruments in higher volume private and hospital labs. Benchtop analyzers performing low volume automated POC testing in clinics and offices could represent an increasingly poor proposition for physician offices and other POC testers as market-averaged reimbursement rates slide towards the per-test costs achieved at large labs."[71] - Kalorama Information, a market research company

2.10 Data management

The role of the laboratory is shifting by internal forces like the adoption of new technology as well as external ones such as consumerism, information availability, and the development of complicated data streams. Laboratory professionals are moving to a role that places them in the center of the data stream. As such, effective data collection and management is becoming more important than ever. This requires not only quality tools but also staff-friendly processes that can easily be followed and updated.

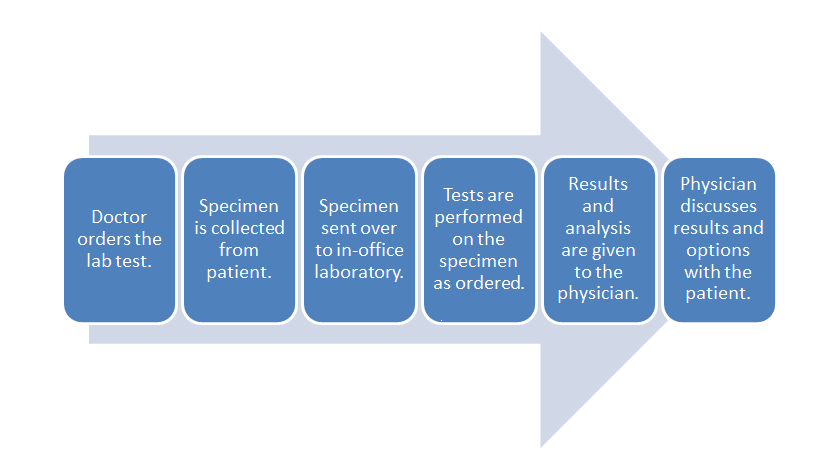

- POL workflow:

The above diagram shows the typical workflow for POL data management. While managing this workflow is important, the data associated with it go beyond ordinary practice function; these data can be used to assist with tracking population health for the patients or be combined with financial data such as billing or spending on supplies.

Other data streams may be generated outside this typical workflow as well. Meaningful Use Stage 3 will eventually require EHRs to accept patient-generated data. These data can come from tracking tools like Fitbits or from glucometers used by the patient.[73] Such data can aid the physician with diagnosis by giving them more data points to examine, but this may also impact the data management methods of the practice.

This area is a future frontier in the quest to use technology as a means of improving outcomes while driving costs down. The popularity of these patient devices and the trend towards using technology for healthcare purposes is drawing physician interest in using such devices for expanded monitoring of patients, with indicators supporting this trend on the development side.[73] The Scanadu Scanaflo, which "measures up to 12 reagents" as well as pH, represents another such device. Scanaflo is still in development, but it will work with a smartphone app and allow patients to monitor many areas of their health from home.[39] Results can be stored and interpreted via the app, and that data can eventually make its way into a physician's Stage 3-compliant EHR. (An interesting video about generating data at home with Scanadu devices can be viewed here.)

2.10.1 Data management tools

Laboratory data management for a POL is generally done via a laboratory information system (LIS), a software system that records, manages, and stores data for clinical laboratories. The LIS is usually able to connect to laboratory instruments, track orders, and record and store results. A modern LIS is also capable of integrating with an electronic health record (EHR) — a digital patient record capable of being shared across different health care settings — to allow the results to be stored in the complete patient record. This is an easier task for the POL, but if the results are coming in from an outside laboratory, an online healthcare marketplace service such as Health Gorilla (formerly Informedika) can be of great assistance.

Other tools for connecting the lab with the physician office are popping up too. Clinical information exchange systems are being designed to optimize workflows using application programming interfaces (APIs) and web services technology to connect systems.[74] Computerized provider order entry (CPOE) systems are also increasingly being used. In many cases these systems are used for entering drug orders, but these systems can also be used to enter laboratory testing orders. This offers an opportunity for laboratory professionals to assist physicians with choosing the appropriate test.[75]

When done well, laboratory data management can allow physician offices to track data for multiple business processes as well as patient care. This is made easier when software systems are interfaced and the staff is trained in their use. As such, laboratory personnel should be part of the data management system decision making processes, especially given the introduction of patient-generated laboratory data. This also provides an opportunity for laboratory directors to get involved, as they are the ones ultimately responsible for compliance with regulatory issues.

See the Data Management section of this guide for more information.

2.10.2 Data management challenges

As mentioned previously, changes to HIPAA rules now require laboratories to give results to the patient within 30 days of a written request by patient or authorized agent. This complicates the process of managing laboratory data, which should be kept in both the LIS and the patient EHR. Rapid data transfer to these systems can be facilitated through an interface with lab instruments, extracting and storing the results. Some POL instruments can do this directly through an interface while others (a point-of-care glucometer, for example) may need to have its data entered in manually.

Another challenge for physicians is deciding on a certified EHR. Slightly more than 1,400 Meaningful Use Stage 1 certified EHRs (about 72 percent of all certified EHRs) had not become Stage 2 certified by the end of 2014. This puts many laboratories in a difficult position because they must create new interfaces for physicians forced to replace their previous EHR. However, laboratory operators have seen all kinds of EHRs and are in a unique position to advise physicians on how to best replace their EHR. This is an advantage for the POL: one can buy an LIS and an EHR at the same time and get opinions from other laboratories about how well they interface.[76]

However, with Meaningful Use Stage 3 requirements due to take effect in 2016, and seeing as how more than 70 percent of EHRs are not Stage 2-compliant, how many options will actually be ready to accept patient-generated data via Stage 3 compliancy?

CLIA regulations hold laboratory directors responsible for compliance with data reporting EHR requirements. In-house laboratories such as the POL are not impacted by some of the challenges regarding CLIA requirements; however, they can still be impacted by the requirements to collect data from multiple sources and put those data into the patient record.[77] As most POLs are operating on a CLIA certificate of waiver and the requirements for the laboratory director are minimal, an air of complacency can evolve in the POL environment. However, a POL's laboratory director must focus on being proactively involved with data collection and management functions as well as the EHR and LIS selection and familiarization process.

References

- ↑ "Laboratories by Type of Facility" (PDF). Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. March 2022. https://www.cms.gov/Regulations-and-Guidance/Legislation/CLIA/downloads/factype.pdf. Retrieved 17 April 2022.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5 2.6 2.7 Garrels, Marti; Oatis, Carol S. (2014). Laboratory and Diagnostic Testing in Ambulatory Care: A Guide for Healthcare Professionals (3rd ed.). Elsevier Health Sciences. pp. 368. ISBN 9780323292368. https://books.google.com/books?id=LM9sBQAAQBAJ. Retrieved 18 April 2022.

- ↑ "Careers in Pathology and Medical Laboratory Science" (PDF). American Society for Clinical Pathology. Archived from the original on 31 October 2015. https://web.archive.org/web/20151031084059/http://www.ascp.org/pdf/CareerBooklet.aspx. Retrieved 18 April 2022.

- ↑ "Laboratory Safety Standards". American National Standards Institute. 2022. https://webstore.ansi.org/industry/laboratory-safety. Retrieved 18 April 2022.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, Division of Laboratory Services (March 2022). "Enrollment, CLIA exempt states, and certification of accreditation by organization" (PDF). http://www.cms.gov/Regulations-and-Guidance/Legislation/CLIA/Downloads/statupda.pdf. Retrieved 18 April 2022.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (6 August 2018). "Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments (CLIA): Test complexities". https://www.cdc.gov/clia/test-complexities.html. Retrieved 18 April 2022.

- ↑ "CLIA - Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments - Currently Waived Analytes". U.S. Food and Drug Administration. 18 April 2022. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/cdrh/cfdocs/cfClia/analyteswaived.cfm. Retrieved 18 April 2022.

- ↑ Kulczycki, Michael (1 April 2014). "Focusing on Provider-Performed Microscopy Procedure Requirements for Ambulatory Health Care". Ambulatory Buzz. The Joint Commission. Archived from the original on 01 March 2016. https://web.archive.org/web/20160301192508/http://www.jointcommission.org/musingsambulatory_patient_safety/focusing_provider_microscopy_procedure_req_ambulatory_health_care/. Retrieved 18 April 2022.

- ↑ Taylor, Jean M.; Stein, Gary C.; Weinberg, Sandy (2002). "Chapter 1: Historical Perspective". Good Laboratory Practice Regulations (3rd ed.). CRC Press. pp. 1–24. ISBN 9780203911082. https://books.google.com/books?id=50P7CAAAQBAJ&pg=PA1. Retrieved 18 April 2022.

- ↑ Seiler, Jürg P. (2006). "Chapter 1: What Is Good Laboratory Practice All About?". Good Laboratory Practice (2nd ed.). Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 1–58. ISBN 9783540282341. https://books.google.com/books?id=Hhj1sDFIlOYC&pg=PA1. Retrieved 18 April 2022.

- ↑ "Public Law 90-174" (PDF). United States Statutes at Large, Volume 81. 5 December 1967. https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/STATUTE-81/pdf/STATUTE-81-Pg533.pdf. Retrieved 18 April 2022.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 "Public Law 100-578" (PDF). United States Statutes at Large, Volume 102. 31 October 1988. https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/STATUTE-102/pdf/STATUTE-102-Pg2903.pdf. Retrieved 18 April 2022.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 13.2 Cox, Phyllis; Wilken, Danielle (2010). "Chapter 1: Safety in the Laboratory". Palko's Medical Laboratory Procedures (3rd ed.). McGraw-Hill Education. pp. 1–23. ISBN 9780073401959. https://books.google.com/books?id=6uWWPQAACAAJ. Retrieved 18 April 2022.

- ↑ "Examples of Common Laboratory Chemicals and their Hazard Class". National Institutes of Health, Office of Management. 27 November 2012. https://orf.od.nih.gov/EnvironmentalProtection/WasteDisposal/Pages/Examples+of+Common+Laboratory+ChemicalsandtheirHazardClass.aspx. Retrieved 18 April 2022.

- ↑ "CLIA Program and HIPAA Privacy Rule; Patients' Access to Test Reports" (PDF). Federal Register 79 (25): 7290–7316. 6 February 2014. https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/FR-2014-02-06/pdf/2014-02280.pdf. Retrieved 18 April 2022.

- ↑ Robeznieks, A. (3 March 2021). "Common HIPAA violations physicians should guard against". American Medical Associations. https://www.ama-assn.org/practice-management/hipaa/common-hipaa-violations-physicians-should-guard-against. Retrieved 18 April 2022.

- ↑ Hughes, D.; Cammarata, B. (16 January 2014). "Clinical labs under ACA: Challenge and opportunity". Law360. https://www.law360.com/articles/500623/clinical-labs-under-aca-challenge-and-opportunity. Retrieved 18 April 2022.

- ↑ Laughlin, S. (22 October 2015). "The LIS, the healthcare market, and the POL". Medical Laboratory Observer. https://www.mlo-online.com/information-technology/lis/article/13008470/the-lis-the-healthcare-market-and-the-pol. Retrieved 18 April 2022.

- ↑ Rothenberg, I.Z. (9 July 2018). "Point of Care Testing (POCT): What’s New?". Physicians Office Resource. https://www.physiciansofficeresource.com/articles/laboratory/point-of-care-testing-poct-what-s-new/. Retrieved 18 April 2022.

- ↑ Rothenberg, I.Z. (1 July 2021). "The Increase in Waived Testing in the Physician Office". Physicians Office Resource. https://www.physiciansofficeresource.com/articles/finance/waived-testing/. Retrieved 18 April 2022.

- ↑ "CLIA Categorizations". U.S. Food and Drug Administration. 25 February 2020. https://www.fda.gov/medical-devices/ivd-regulatory-assistance/clia-categorizations. Retrieved 18 April 2022.

- ↑ "Waived Tests". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 3 September 2021. https://www.cdc.gov/labquality/waived-tests.html. Retrieved April 18, 2022.

- ↑ "Certificate of Waiver Laboratory Project". Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. 27 February 2014. Archived from the original on 02 January 2019. https://web.archive.org/web/20190102181225/https://www.cms.gov/Regulations-and-Guidance/Legislation/CLIA/Certificate_of_-Waiver_Laboratory_Project.html. Retrieved 18 April 2022.

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 "How to Apply for a CLIA Certificate, Including International Laboratories". Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. 1 December 2021. https://www.cms.gov/Regulations-and-Guidance/Legislation/CLIA/How_to_Apply_for_a_CLIA_Certificate_International_Laboratories. Retrieved 18 April 2022.

- ↑ Stiles, K. (2020). "Nebraska Public Health Laboratory Point of Care Waived Testing for Long Term Care Facilities". Nebraska Public Health Laboratory. https://www.nehca.org/wp-content/uploads/POC-Waived-Training-LTC.pdf. Retrieved 18 April 2022.

- ↑ 26.0 26.1 26.2 Thill, M. (October 2020). "Selling Moderate Complexity". Repertoire. https://repertoiremag.com/selling-moderate-complexity.html. Retrieved 18 April 2022.

- ↑ Kiechle, Frederick L.Main, Rhonda Ingram (2002). The Hitchhiker's Guide to Improving Efficiency in the Clinical Laboratory. American Association for Clinical Chemistry. pp. 132. ISBN 9781890883720. https://books.google.com/books?id=ud55aVHAiTQC. Retrieved 18 April 2022.

- ↑ "Point-of-Care Diagnostic Testing". Research Portfolio Online Reporting Tools. National Institutes of Health. 30 June 2018. https://web.archive.org/web/20190211145517/http://report.nih.gov/nihfactsheets/ViewFactSheet.aspx?csid=112. Retrieved 18 April 2022.

- ↑ "Point Of Care Testing". College of American Pathologists. September 2013. http://www.cap.org/apps//cap.portal?_nfpb=true&cntvwrPtlt_actionOverride=%2Fportlets%2FcontentViewer%2Fshow&_windowLabel=cntvwrPtlt&cntvwrPtlt{actionForm.contentReference}=policies%2Fpolicy_appII.html. [dead link]

- ↑ Futrell, K. (22 June 2017). "Looking at POCT through a new 'value' lens". Medical Laboratory Observer. https://www.mlo-online.com/continuing-education/article/13009205/looking-at-poct-through-a-new-value-lens. Retrieved 18 April 2022.

- ↑ Dhawan, Atam P. (2018). "Editorial Trends and Challenges in Translation of Point-of-Care Technologies in Healthcare". IEEE Journal of Translational Engineering in Health and Medicine 6: 1–8. doi:10.1109/JTEHM.2018.2866162. ISSN 2168-2372. PMC PMC6225954. PMID 30430044. https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/document/8485509/.

- ↑ Plotts, A. (21 September 2021). "Creating Meaningful Interoperability for Patient Healthcare Records". Labcorp. https://www.labcorp.com/unique-perspectives/blog/creating-meaningful-interoperability-patient-healthcare-records. Retrieved 20 April 2022.

- ↑ Juluru, K.; Weitz, A.; Fleurence, R.L. et al. (11 February 2022). "Reporting COVID-19 Self-Test Results: The Next Frontier" (in en). Health Affairs. doi:10.1377/forefront.20220209.919199. http://www.healthaffairs.org/do/10.1377/forefront.20220209.919199/full/.

- ↑ 34.0 34.1 "Waived and Provider Performed Microscopy (PPM) Tests". American Academy of Family Physicians. https://www.aafp.org/family-physician/practice-and-career/managing-your-practice/clia/waived-ppm-tests.html. Retrieved 20 April 2022.

- ↑ "Provider-performed Microscopy Procedures" (PDF). Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. https://www.cms.gov/Regulations-and-Guidance/Legislation/CLIA/downloads/ppmplist.pdf. Retrieved 20 April 2022.

- ↑ 36.0 36.1 36.2 "Integrating Laboratories Into the PCMH Model of Health Care Delivery: A COLA White Paper" (PDF). 2014. p. 3–4. http://www.cola.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/06/COLA_14194-PCMH-Whitepaper.pdf. Retrieved 20 April 2022.

- ↑ "Strengthening Clinical Laboratories". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 15 November 2018. https://www.cdc.gov/csels/dls/strengthening-clinical-labs.html. Retrieved 20 April 2022.

- ↑ Goyal, Nidhi (4 April 2015). "VeinViewer Means No More Poking People Relentlessly to Locate Veins". Industry Tap. https://www.industrytap.com/veinviewer-means-no-poking-people-relentlessly-locate-veins/27706. Retrieved 20 April 2022.

- ↑ 39.0 39.1 Buhr, Sarah (18 February 2015). "Scanadu’s New Pee Stick Puts The Medical Lab On Your Smartphone". Tech Crunch. Yahoo. https://techcrunch.com/2015/02/18/scanadus-new-pee-stick-puts-the-medical-lab-on-your-smartphone/. Retrieved 20 April 2022.

- ↑ {{cite web |url=https://healthy.io/about-us |title=About Us |publisher=Healthy.io |accessdate=20 April 2022}

- ↑ 41.0 41.1 41.2 Park, Richard (13 October 2014). "Examining the Physician Office Lab Market: Growth and Reimbursement". Medical Design Technology. Advantage Business Media. Archived from the original on 14 September 2015. https://web.archive.org/web/20150915023725/http://www.mdtmag.com/blog/2014/10/examining-physician-office-lab-market-growth-and-reimbursement. Retrieved 01 June 2015.

- ↑ "How and Where IVD Will Find Growth in the Global POL Market – Part 2". Kalorama Information. November 2014. Archived from the original on 17 April 2015. https://web.archive.org/web/20150417204832/http://www.kaloramainformation.com/article/2014-11/How-and-Where-IVD-Will-Find-Growth-Global-POL-Market-%E2%80%93-Part-2. Retrieved 20 April 2022.

- ↑ Park, Richard (29 September 2014). "Examining the Physician Office Lab Market: CLIA and Technology". Medical Design Technology. Advantage Business Media. Archived from the original on 15 September 2015. https://web.archive.org/web/20150915023715/http://www.mdtmag.com/blog/2014/09/examining-physician-office-lab-market-clia-and-technology. Retrieved 20 April 2022.

- ↑ Health Industry Distributors Association (October 2020). "2020 U.S. Laboratory Market Report". Research and Markets. https://www.researchandmarkets.com/reports/5178165/2020-u-s-laboratory-market-report. Retrieved 20 April 2022.

- ↑ 45.0 45.1 "Administrative Procedures for CLIA Categorization: Guidance for Industry and Food and Drug Administration Staff" (PDF). U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. 12 March 2014. http://www.fda.gov/downloads/MedicalDevices/DeviceRegulationandGuidance/GuidanceDocuments/ucm070889.pdf. Retrieved 01 June 2015.

- ↑ 46.0 46.1 46.2 Wirt, Tammy (24 March 2014). "NWS HHS FDA CRDH" (PDF). U.S. Food and Drug Administration. http://www.fda.gov/downloads/Training/CDRHLearn/UCM390761.pdf. Retrieved 01 June 2015.

- ↑ "Fact Sheet: Medical Device User Fee Amendments of 2012". U.S. Food and Drug Administration. 3 August 2012. http://www.fda.gov/RegulatoryInformation/Legislation/FederalFoodDrugandCosmeticActFDCAct/SignificantAmendmentstotheFDCAct/FDASIA/ucm313695.htm. Retrieved 01 June 2015.

- ↑ Mullen, Allyson B. (19 March 2014). "FDA Issues Revised Final Guidance Regarding Administrative Procedures for CLIA Categorization". FDA Law Blog. Hyman, Phelps & McNamara, P.C. http://www.fdalawblog.net/fda_law_blog_hyman_phelps/2014/03/fda-issues-revised-final-guidance-regarding-administrative-procedures-for-clia-categorization.html. Retrieved 01 June 2015.

- ↑ Rath, Prakash (5 March 2014). "Administrative Changes to FDA’s CLIA Categorization Program" (PDF). U.S. Food and Drug Administration. http://ftp.cdc.gov/pub/CLIAC_meeting_presentations/pdf/Addenda/cliac0314/04_Rath_Admin%20Changes%20to%20FDA%27s%20CLIA%20Program.pdf. Retrieved 01 June 2015.

- ↑ "CLIA Waiver by Application". U.S. Food and Drug Administration. 26 March 2015. http://www.fda.gov/MedicalDevices/DeviceRegulationandGuidance/IVDRegulatoryAssistance/ucm393233.htm. Retrieved 01 June 2015.

- ↑ "Quidel Receives Simultaneous FDA Clearance And CLIA Waiver For Its Sofia® Strep A+ Fluorescent Immunoassay (FIA) Via The FDA's New Dual Submission Program". Med Device Online. VertMarkets, Inc. 17 December 2014. http://www.meddeviceonline.com/doc/quidel-receives-simultaneous-fda-clearance-and-clia-waiver-0001. Retrieved 01 June 2015.

- ↑ Mezher, M. (25 February 2020). "FDA Finalizes Guidances on CLIA Waiver Applications, 510(k) Dual Submissions". Regulatory Affairs Professionals Society. https://www.raps.org/news-and-articles/news-articles/2020/2/fda-finalizes-guidances-on-clia-waiver-application. Retrieved 20 April 2022.

- ↑ "Trinity Biotech Announces CLIA Waiver of Rapid Syphilis Test". GlobeNewswire, Inc. 16 December 2014. http://globenewswire.com/news-release/2014/12/16/691813/10112606/en/Trinity-Biotech-Announces-CLIA-Waiver-of-Rapid-Syphilis-Test.html. Retrieved 26 May 2015.

- ↑ "HIV testing - prevalent CLIA waived tests". Percepta Associates, Inc. 12 March 2015. http://www.perceptaassociates.com/hiv-testing-clia-waived-tests/. Retrieved 26 May 2015.

- ↑ "Trinity Biotech Receives CLIA Waiver for Uni-Gold(TM) Recombigen(R) HIV Test". PR Newswire Association LLC. 10 November 2014. http://www.prnewswire.com/news-releases/trinity-biotech-receives-clia-waiver-for-uni-goldtm-recombigenr-hiv-test-75323487.html. Retrieved 26 May 2015.

- ↑ 56.0 56.1 56.2 Johnson, Madeleine (26 April 2015). "Cepheid Sees 'Significant Opportunity' in Menu Expansion, CLIA Market". GenomeWeb. Genomeweb LLC. https://www.genomeweb.com/business-news/cepheid-sees-significant-opportunity-menu-expansion-clia-market. Retrieved 21 May 2015.

- ↑ 57.0 57.1 Johnson, Madeleine (19 June 2014). "With FDA-Cleared Flu Test, Alere Launches Isothermal MDx Platform for US Clinical Market". GenomeWeb. Genomeweb LLC. https://www.genomeweb.com/pcrsample-prep/fda-cleared-flu-test-alere-launches-isothermal-mdx-platform-us-clinical-market. Retrieved 21 May 2015.

- ↑ 58.0 58.1 58.2 Seiffert, Don (12 January 2015). "FDA waiver of Alere's flu test poses threat to market leader Cepheid". Boston Business Journal. American City Business Journals. http://www.bizjournals.com/boston/blog/bioflash/2015/01/fda-waiver-of-aleres-flu-test-poses-threat-to.html. Retrieved 21 May 2015.

- ↑ Johnson, Madeleine (30 April 2015). "Q&A: BioMérieux's Christine Ginocchio Chats About Her Clinical Lab Career Arc, Syndromic PCR Panels". GenomeWeb. Genomeweb LLC. https://www.genomeweb.com/pcr/qa-biom-rieuxs-christine-ginocchio-chats-about-her-clinical-lab-career-arc-syndromic-pcr-panels. Retrieved 26 May 2015.

- ↑ 60.0 60.1 Johnson, Madeleine (12 January 2015). "With CLIA Waiver and Widespread Flu, Alere Ramps Up Molecular Test Production". GenomeWeb. Genomeweb LLC. https://www.genomeweb.com/pcr/clia-waiver-and-widespread-flu-alere-ramps-molecular-test-production. Retrieved 21 May 2015.

- ↑ "AmericanBio expands product offerings, introduces exclusive CLIA Grade product line". AmericanBio, Inc. 17 October 2014. https://www.americanbio.com/news-events/americanbio-expands-product-offerings-introduces-exclusive-clia-grade-product-line1. Retrieved 27 May 2015.

- ↑ "How to get a CLIA Waiver for your Medical Device: One and a Half Day In-person Seminar 2015 (Newark, NJ)". Research and Markets. May 2015. http://www.researchandmarkets.com/reports/3215400/how-to-get-a-clia-waiver-for-your-medical-device. Retrieved 27 May 2015.

- ↑ ""CLIA Waivers: The What, The Why, and The How" Webinar". National Institutes of Health. 15 April 2015. http://www.nibib.nih.gov/news-events/meetings-events/clia-waivers-what-why-and-how-webinar. Retrieved 27 May 2015.

- ↑ "Regulatory Solutions". Precision for Medicine. http://www.precisionformedicine.com/regulatory-solutions/. Retrieved 27 May 2015.

- ↑ Ubel, Peter (12 February 2014). "Is The Profit Motive Ruining American Healthcare?". Forbes.com. Forbes, Inc. http://www.forbes.com/sites/peterubel/2014/02/12/is-the-profit-motive-ruining-american-healthcare/. Retrieved 27 May 2015.

- ↑ 66.0 66.1 Collen, Mark (2012). "Profit-Driven Drug Testing". Journal of Pain & Palliative Care Pharmacotherapy (26): 13–17. doi:10.3109/15360288.2011.650358. http://www.academia.edu/7840929/Profit-driven_drug_testing. Retrieved 27 May 2015.

- ↑ Weaver, Christopher; Matthews, Anna-Wilde (10 November 2014). "Doctors Cash In on Drug Tests for Seniors, and Medicare Pays the Bill". The Wall Street Journal. Dow Jones & Company, Inc. http://www.wsj.com/articles/doctors-cash-in-on-drug-tests-for-seniors-and-medicare-pays-the-bill-1415676782. Retrieved 01 June 2015.

- ↑ "Top 10 Tests In Physician Office Revealed". Kalorama Information. 10 December 2014. http://www.kaloramainformation.com/about/release.asp?id=3686. Retrieved 05 June 2015.

- ↑ "Report: Five Fastest-Growing Tests in Physician Office Labs". PR Newswire. 18 December 2014. http://www.prnewswire.com/news-releases/report-five-fastest-growing-tests-in-physician-office-labs-300010866.html. Retrieved 05 June 2015.

- ↑ 71.0 71.1 "Recapping the 'Doc Fix' Act's Impacts on Medicare Lab Reimbursement". Kalorama Information. June 2014. http://www.kaloramainformation.com/article/2014-06/Recapping-Doc-Fix-Acts-Impacts-Medicare-Lab-Reimbursement. Retrieved 02 June 2015.

- ↑ 72.0 72.1 Malone, Bill (1 June 2014). "A New Era for Lab Reimbursement". Clinical Laboratory News. American Association for Clinical Chemistry. https://www.aacc.org/publications/cln/articles/2014/june/lab-reimbursement. Retrieved 02 June 2015.

- ↑ 73.0 73.1 McLeod, Pamela Scherer (19 March 2015). "Physicians Use Fitness Trackers to Monitor Patients in Real-time, Even as Developers Work to Incorporate Medical Laboratory Tests into the Devices". Dark Daily. Dark Intelligence Group, Inc. http://www.darkdaily.com/physicians-use-fitness-trackers-to-monitor-patients-in-real-time-even-as-developers-work-to-incorporate-medical-laboratory-tests-into-the-devices-528. Retrieved 14 April 2015.

- ↑ Michel, Robert (30 March 2015). "How Medical Laboratories Help Physicians Overcome the Failure of Many EHR Systems to Support Effective Lab Test Ordering and Lab Result Reporting". DarkDaily.com. Dark Intelligence Group, Inc. http://www.darkdaily.com/how-medical-laboratories-help-physicians-overcome-the-failure-of-many-ehr-systems-to-support-effective-lab-test-ordering-and-lab-result-reporting-330.

- ↑ Sinard, John (2006). Practical Pathology Informatics: Demystifying Informatics for the Practicing Anatomic Pathologist. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 412. ISBN 9780387280585. https://books.google.com/books?id=WerUyK618fcC. Retrieved 14 April 2015.

- ↑ Michel, Robert (19 March 2015). "Most Clinical Laboratories and Pathology Groups Unprepared to Help Client Physicians Meet Meaningful Use Stage 2 Criteria". Dark Daily. Dark Intelligence Group, Inc. http://www.darkdaily.com/most-clinical-laboratories-and-pathology-groups-unprepared-to-help-client-physicians-meet-meaningful-use-stage-2-criteria. Retrieved 14 April 2015.

- ↑ Henricks, Walter H. (18 March 2015). "Accreditation and Regulatory Implications of Electronic Health Records for Laboratory Reporting". InsuranceNewsNet.com, Inc. http://insurancenewsnet.com/oarticle/2015/03/18/accreditation-and-regulatory-implications-of-electronic-health-records-for-labor-a-606123.html. Retrieved 14 April 2015.

Citation information for this chapter

Chapter: 2. The clinical environment

Title: The Comprehensive Guide to Physician Office Laboratory Setup and Operation

Author for citation: Shawn E. Douglas

License for content: Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International

Publication date: June 2015