Journal:Smart grids and ethics: A case study

| Full article title | Smart grids and ethics: A case study |

|---|---|

| Journal | ORBIT Journal |

| Author(s) | Hatzakis, Tally; Rodrigues, Rowena; Wright, David |

| Author affiliation(s) | Trilateral Research |

| Primary contact | Email: Tally dot Hatzakis at trilateralresearch dot com |

| Year published | 2019 |

| Volume and issue | 2(2) |

| Page(s) | 108 |

| DOI | 10.29297/orbit.v2i2.108 |

| ISSN | 2515-8562 |

| Distribution license | Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International |

| Website | https://www.orbit-rri.org/ojs/index.php/orbit/article/view/108 |

| Download | https://www.orbit-rri.org/ojs/index.php/orbit/article/view/108/119 (PDF) |

Abstract

This case study explores the principal ethical issues that occur in the use of smart information systems (SIS) in smart grids and offers suggestions as to how they might be addressed. Key issues highlighted in the literature are reviewed. The empirical case study describes one of the largest distribution system operators (DSOs) in the Netherlands. The aim of this case study is to identify which ethical issues arise from the use of SIS in smart grids, the current efforts of the organization to address them, and whether practitioners are facing additional issues not addressed in current literature. The literature review highlights mainly ethical issues around health and safety, privacy and informed consent, cyber-risks and energy security, affordability, equity, and sustainability. The key topics raised by interviewees revolved around privacy and to some extent cybersecurity. This may be due to the prevalence of the issue within the sector and the company in particular or due to the positions held by interviewees in the organization. Issues of sectorial dynamics and public trust, codes of conduct, and regulation were raised in the interviews, which are not discussed in the literature. Rather, this paper hence highlights the ability of case studies to identify ethical issues not covered (or covered to an inadequate degree) in the academic literature which are facing practitioners in the energy sector.

Keywords: smart grids, ethics, big data

Introduction

As a crucial element of our overall energy and climate strategy, we need to ensure that our energy infrastructure is sustainable, goal-oriented and operational. - Miguel Arias Cañete, European Commissioner for Climate Action and Energy

The energy sector represents the critical infrastructure upon which all other economic activities, modern life conveniences, and services—including the wide spectrum of information and communication technologies (ICT)—are based. The expected demands on the energy sector over the coming years will be immense due to the proliferation of ICT technologies and their ubiquitous use in all aspects of social and economic life.

Many factors will increase society’s electricity demands in Europe, such as the advent of internet of things[a] (IoT) sensors, the increased digitization of social life due to robotics and blockchain[b], the further digitization of industry, and the transition from vehicles using fossil fuel to electric vehicles. In parallel, to tackle climate change and decrease reliance on imported fossil fuels, Europe is pushing for greater integration of renewables in the mix of energy production sources. In combination, both put great pressure on the capacity of Europe’s pre-existing energy distribution network infrastructure, which cannot currently scale up to meet expected demands, at least not if managed in traditional ways. European countries have two options[1]: invest in upgrading energy infrastructure networks or optimize the use of the existing infrastructure capacity by utilizing smart information systems (SIS).

On the supply side, improved efficiency can derive from better management of volatile renewable energy generation solutions, improved maintenance of the energy grid infrastructure, and even enhancing modelling of demand needs and thereby infrastructure investments. On the demand side, improved efficiency can derive from shifting energy consumption patterns through real-time demand-response pricing and load balancing across the grid.[2]

While the use of SIS in energy distribution, i.e., in smart grids, holds the promise that countries will be able to ensure affordable and sustainable energy for the ever-increasing energy demands of smart living[2], it presents a number of ethical challenges.[3]

This case study reviews the social, ethical, and human rights issues arising from the utilization of SIS (artificial intelligence [AI] technologies and big data analytics) in the energy sector, and in particular in smart energy grids. The next section explains the use of SIS in the energy sector and in particular in energy distribution via energy grids. The section after, a review of the current implementation of big data and AI-powered analytics in the energy sector and the ethical issues that may arise as a result are reviewed. The section focuses on the types of SIS technologies being used and highlights the range of social and ethical issues surrounding their use. The third section will analyse a Dutch distribution system operator (DSO) company, while the fourth will explore and critically evaluate ethical issues arising from the introduction of SIS technologies in smart grids in practice, through interviews conducted with staff members. This section will evaluate whether there are policies and procedures in place to tackle these issues and what the protocol is for addressing concerns.

The use of SIS in smart grids

The use of SIS in energy promises to ensure sustainable affordable energy for the ever-increasing demands of smart living without big investments in the energy distribution systems in two ways. First, SIS allow for the optimizations of energy supply and demand management from existing resources. Smart grids involve a host of intelligent technologies to improve the management of the energy distribution network that connects energy producers with consumers. These include:

- sensors that collect real-time information about energy quality at different points along the distribution network;

- sensors that collect information about consumption via smart meters installed in people’s houses;

- a mechanism to analyze all collected data in order to better predict energy needs, optimize supply and demand, and swiftly respond to unpredictable changes in either; and

- a means to provide the necessary insights to design incentivization programs to change energy consumption behaviors.

Second, smart grids enable the safe incorporation of renewables and green electricity into the grid. While renewables are a key component of Europe’s sustainability goals, their integration poses a challenge for traditional power grids. Surges of power generated by renewables may overcharge the grid leading to power cuts and costly maintenance work, or compromise the reliability and quality of the electricity provided.[4] SIS allow to safely manage the risks from integrating renewables into the energy production mix. According to Liang[5], quality issues arise from:

- voltage and frequency fluctuations that can be caused by the intermittent nature of renewable energy production due to changing weather conditions, and

- harmonic (wavelength) distortions introduced by electronic devices utilized in renewable energy generation.

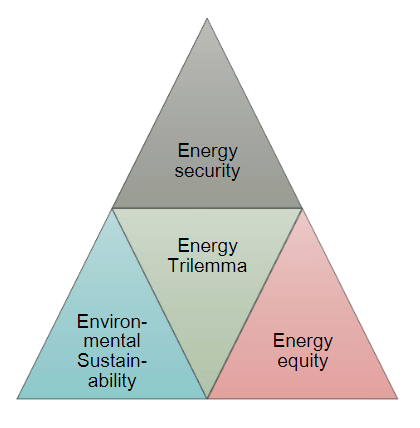

Such risks introduced by renewable energy technologies may affect the performance of electrical equipment, particularly sensitive electronic devices. A number of problems can compromise the performance and reliability of electronic systems, such as equipment shutoff, errors or memory loss, loss of data and burned circuit boards, reader errors, and the like. To handle such volatility requires the monitoring and control of electricity from the point of production to the point of consumption, as well as real-time adjustments in energy distribution depending on fluctuations in weather conditions, fluctuations in energy generation and demand, and other factors that can affect the quality of the energy supply.[6] Hence, the use of smart grid technologies can help solve the World Energy Council's "Energy Trilemma": how to secure (energy security) affordable energy for all (energy equity) in a sustainable manner (environmental sustainability).

|

Energy security: Effective management of primary energy supply from domestic and external sources, reliability of energy infrastructure, and ability of energy provide to meet current and future demand.

Energy equity: Accessibility and affordability of energy supply across the population.

Environmental sustainability: Encompasses achievement of supply- and demand-side energy efficiencies and development of energy supply from renewable and other low-carbon sources.

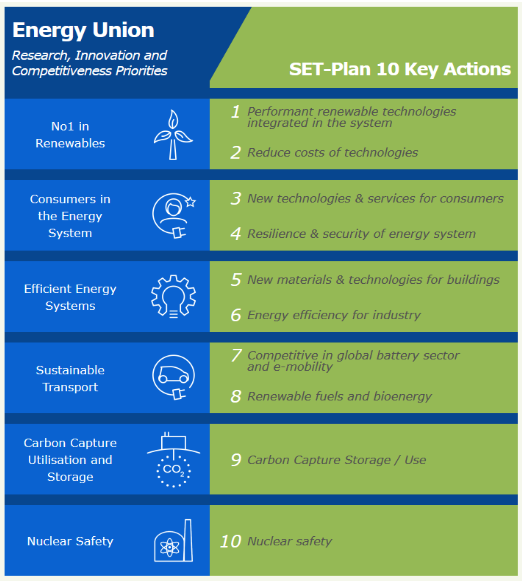

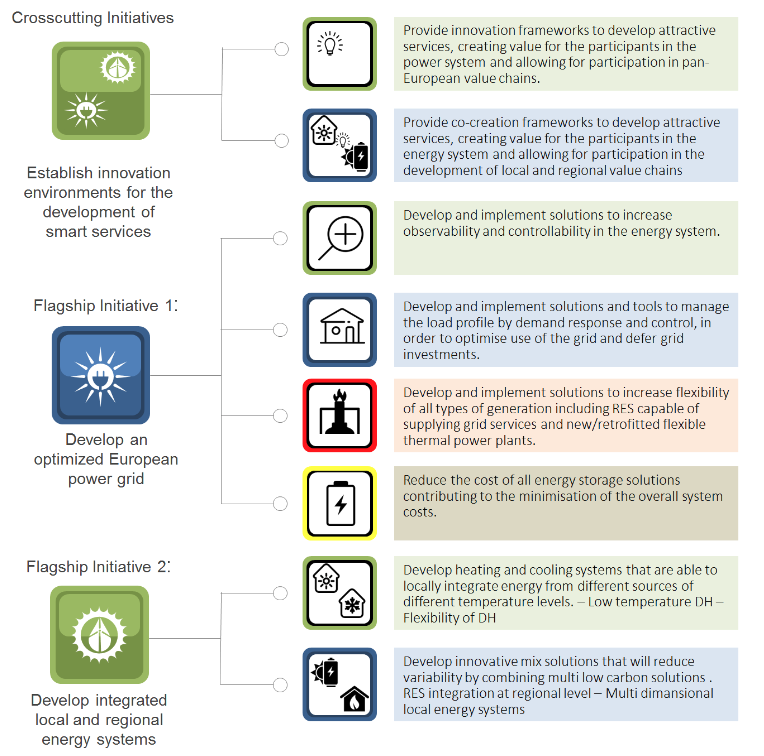

The application of SIS in the energy sector in Europe is deployed within the wider context of accelerating the European Energy System transformation set out by the Integrated Strategic Energy Technology Plan (SET-Plan).[2] The SET plan was originally conceived in 2008 and amended in 2015 to introduce steps towards a pan-European Energy Union. It seeks to accelerate knowledge and technology transfer and adoption, foster research and development (R&D), and drive the uptake of low-carbon energy technologies to reach energy and climate change goals and achieve the transition to a low-carbon economy by 2050.[2] The plan makes provisions for dealing with the technological challenges posed by renewables, their volatility in energy production, and their distributed nature. It also makes provisions for the integration of the upcoming electric transport systems and IoTs in an integrated energy system, which will require new protocols of data exchange and collaboration across the energy, transport, and ICT sectors and regulators. The plan sets out a number of priorities to facilitate innovation in the sector with the view to develop and implement solutions that can help (a) maximize the value and lifetime of the existing grid to defer large lump sum investments in costly new infrastructure, and (b) integrate power from renewable generation sources and distribute it at a local or regional level (see Figure 2 below).

|

Smart grids involve a host of intelligent technologies to improve monitoring and control of energy consumption, and communication technologies to address operational issues around distribution and production, but also collect real-time information about energy consumption from consumers via smart meters. It is worth noting that such technologies do not substitute but complement traditional grids. Such technologies comprise:

- HAN (Home Area Networks), which ensure the communication between smart meters and smart appliances;

- WASA (Wide Area Situational Awareness), which provides monitoring of performance and ensures dynamic prevention and response services when necessary;

- SCADA (Substation Supervisory Control and Data Acquisition) systems, which are used to monitor and control energy plants or equipment, as well as transportation;

- AMI (Advanced Metering Infrastructure), which allows smart meters to communicate with the grid;

- PMUs (Phasor Measurement Units), which allow the concurrent, real-time monitoring of energy supply systems by measuring electricity current and voltage by amplitude and phase across selected locations (stations) of the grid;

- WAMPAC (Wide Area Monitoring Protection and Control), which ensures the security of the power system;

- IEDs (Intelligent Electronic Devices), smart devices which can communicate with each other and with SCADA to enable fault detection and rectification; and

- FACTS (Flexible AC Transmission Systems, such as Unified Power Flow Controllers), which enable long-distance transport and integration of renewable energy sources.

Energy data from a variety of sources is combined and analysed, in order to[7]:

- Develop a responsive power grid to achieve appropriate levels of reliability, resilience, and economic efficiency in the face of the fluctuations of renewable power generation. Smart power grids optimize not only the seamless integration of sustainable power, but also its storage, its connection with other networks (e.g., heat and cold, transport), and the inter-regional exchange of power.

- Develop local and regional energy systems to facilitate the integration of renewables in the local or regional supply by 2030, and enable the inter-regional exchange of spare energy, as well as the security and resilience of European energy systems (see Figure 3 below).

|

Smart grid management systems require the analysis of real-time energy consumption data and energy production data. AMI collect household energy consumption data, as well as data relating to voltage quality, power quality, active energy, and reactive power, as well as diagnostics information about the condition and control of the smart meter itself (pinging the meter) and operational status (indicators, alarms, and error messages) from the meter.

The use of artificial intelligence and big data analytics in the energy sector is nascent. It is contingent upon the widespread adoption of smart meters by the public. According to a study by the European Commission[1], there were 45 million electricity smart meters installed in Finland, Italy, and Sweden, representing only 25% of the potential market penetration in these countries. This number has increased to around 60% by 2018, but it still lags behind the expected level of 80% for smart meter penetration, which is necessary to require and justify the use of such systems for energy management. Nevertheless, progress towards this goal is likely to be rapid. In 16 European Member States (Austria, Denmark, Estonia, Finland, France, Greece, Ireland, Italy, Luxemburg, Malta, Netherlands, Poland, Romania, Spain, Sweden, and the U.K.) rollouts of smart meters by 2020 or earlier are planned, and Poland and Romania have already seen consumer benefits.

In Germany, Latvia, and Slovakia, smart metering was found to be economically justified, but only for particular groups of customers, while the business case in terms of consumer benefits across the population was either negative or inconclusive in Belgium, the Czech Republic, Germany, Latvia, Lithuania, Portugal, and Slovakia. No roll out plans were available in Bulgaria, Cyprus, Hungary, and Slovenia. In 15 of the 16 Member States, DSOs are responsible for installing smart meters in households which are to be financed via network tariffs. DSOs are responsible for energy distribution infrastructure (mainly electricity and gas piles, exchanges, etc.). DSOs are responsible for not only installing the meters but also for data analytics in most countries, with the exception of Denmark, Estonia, Poland, and the U.K., where data is handled by an independent central data hub; and with the exception of Czech Republic, Germany, and Slovakia, where alternative options for data handling are being considered. The European Commission requires that companies advise customers on how best to balance their energy consumption and enable new energy related services and products. This hinges on access to real-time customer information and raises issues of profiling due to the gathering and storing of sensitive information on the household energy footprint, and stored data in the light of privacy and confidentiality policies.[1]

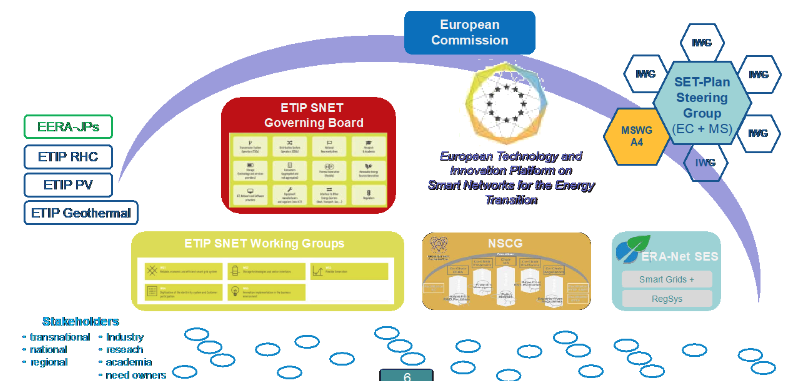

The European Energy Union aspires to connect the networks of its various countries into an integrated energy system. This will require data and knowledge exchange, as well as collaborations across the energy, transport, and ICT sectors from experts and regulators transnationally. The stakeholder landscape in the energy sector is beginning to change, giving rise to the development of cross-sector and cross-country collaborations, such as the European Technology and Innovation Platform on Smart Networks for the Transition, which includes the participation of industry representatives, research, academia, and users (see Figure 4 below). The development of cross-border groups is an interesting development in that there is an international collaboration between DSOs to tackle common issues, which is of particular interest to the case below. Platforms for a public debate with the participation of all types of future energy providers might be more useful in voicing concerns, getting public commitments towards agreed courses of action, and informing policy and regulations.

|

Not only is the relationship between companies within the energy supply chain beginning to change, but also the relationship between companies and customers. Smart utilities promise consumers greater control over their energy consumption choices by collecting and providing customers with real-time information related to energy use and pricing. In addition, the role of end users in the energy value chain is likely to change. With the advent of household renewables solutions, end users will increasingly generate their own power to use, give back to the grid, or exchange at a local level. Hence their role will increasingly change from that of passive consumers of energy to that of an energy prosumer.[c] This will require the development of smart household energy management and billing systems that can become an extension of the existing energy grid.[8]

Typically, end users receive their household energy from energy providers (gas and electricity companies) with whom they have a contract agreement. Many such utilities struggle to garner their customers’ support for the installation of smart meters in households, particularly in Europe and the USA. The two primary concerns fueling the resistance to smart meters relate to health and data privacy issues. Customers, in general, are uncomfortable with commercial organizations, including utilities, possessing such fine-level data that can give away intimate information about one’s lifestyle.[1] Aside from privacy, a number of other ethical issues relate to the use of SIS in smart grids.

Ethical issues of using SIS in smart grids

Despite the wide range of articles on smart grids, there has been very little research on the ethical and legal implications of using SIS technologies in energy. The installation of smart meters in the mainstream is not completed. Consumer research that has taken place relies mostly on pilots with interested parties and looks at the response and use of such technologies, from a functional rather than an ethical perspective. There have been few articles that have cohesively addressed ethical issues of SIS technology in the energy sector. A key issue receiving little attention at present is the implications of energy grids for energy justice and transitional justice to smart grids. Smart grids and their management are only a part of the new energy ecosystem and will likely become the key customer platform and key industry gatekeeper collecting customer insight. There seems to be an underlying mistrust towards energy players and governments about their positions and commitments towards practices that benefit society as a whole once implementation takes place.

Anticipated consumer benefits, such as energy savings, are predicated on the collection and analysis of granular information on household energy usage via smart meters, but these can be used to reveal detailed information about people’s private lives within the home, raising serious questions at a technical and policy level about in-home surveillance and how to address consumers’ privacy interests. These issues have been particularly controversial for gaining user acceptance in the U.S. and Europe.[9] In addition, energy systems are strategic targets for economically-motivated cybercrime, cyberterrorism, and even cyberwar. Smart grids have ICT dependencies that make them more prone to additional security risks (perpetuated by deficiencies in system configurations, network design, software and platform vulnerabilities, or lack of standards and policies). Hence, the use of SIS in the energy sector brings into question societal norms around competing priorities and around the deliberation processes for resolving conflicts and reaching consensus.

The following subsections explore the ethical tensions related to the smart grid. First, ethical issues arising from the impact of smart grids on people’s health are discussed. Next, the implications around eliciting informed consent with privacy and industry practices is addressed. Finally, cybersecurity risks threatening energy security are elaborated upon.

Health and safety: Does the smart grid make us unhealthy?

The wireless communication between smart appliances and the smart grid raises health and safety concerns relating to radio frequency radiation and its possible carcinogenic effects. Similar concerns are associated with cell phone usage. Research conducted by the Electric Power Research Institute on the health implication of the radio-frequency exposure of smart grids indicated that levels fall within acceptable thresholds as defined by the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) for the general public. Yet, adverse public perceptions persist. This has led to various levels of resistance and disputes. For example, in California, citizens and municipalities have resisted the rollout of smart meters, taking the case to the Federal court. The matter also remains open for debate by the International Agency for Research on Cancer.[10] While the case was recently resolved in court, negative perceptions about potential health risks still persist.[11]

Privacy and informed consent: Does the smart grid give away household privacy?

Privacy concerns relate to the granularity of electricity consumption data that can be collected about a household and the intimate lifestyle information that can be inferred from it. For instance, smart meters can tell when someone is at home, whether they are cooking, taking a shower, or watching TV based on monitoring the energy consumption patterns (loads) of such appliances. Customers in general are uncomfortable with commercial organizations, including utilities, possessing such fine-level information.[12] Some people also object to the mandate of being told to have a smart meter installed, unaware of how this decision was made and who were involved in this decision. Objections are then related to trust and transparency.[12][13] To mitigate such concerns, and in response to Europe's General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), utilities have embarked on educating customers regarding their privacy policies, the reasons behind data collection and sharing, accessing of data, and consumer rights.

Ofgem, the government regulator for gas and electricity markets in Great Britain, for example, informs citizens of their rights and suggests that energy suppliers and network companies access smart meter data no more than once every 30 minutes to ensure accurate billing, carry out other essential tasks, and share data (with customer consent) with third parties to offer them new products/services, such as dynamic billing options (see Smart Meters: A Guide to Your Rights at Ofgem.gov.uk). The British Chartered Trading Standards Institute (CTSI) have, however, received complaints from citizens about being misinformed and pressured to install smart meters, potentially breaching Consumer Protection from Unfair Trading Regulations 2008 and raising doubts about the industry’s overall ethical code.[13]

New market players such as aggregators and storage operators are expected to offer dynamic consumption advice as a service to residential customers, contingent upon customers’ consent to share their household consumption data. The company Efficiency 2.0, for example, delivers energy efficiency via customer engagement programs, combining personalized technology portfolios and energy conservation actions with rewards and loyalty incentives to optimize energy savings.[d] This raises the question as to who will be able to afford such services and at what cost. Given the high cost of energy as a percentage of discretionary income for poorer families, it also raises the question as to whether poorer families can afford to opt out from giving their consent if this is the only way to get cheaper energy, or will they be indirectly coerced into it? Furthermore, those who live in, e.g., government-assisted accommodation where electricity is paid by the stateor are occupants in shared private housing where the landlord controls the energy supply may not be given the option to consent individually.

Cyber-risks and security: Do we jeopardize energy security?

Cyber-attacks on the smart grid can do significant damage, yet they are still inadequately addressed due to their low probability of occurrence.[14] Using coordinated, distributed resources, cyber-attacks could potentially target sufficient critical power control equipment simultaneously to originate cascading effects and eventually cause the system to collapse. This would not only be harmful to system integrity but also poses huge risks to human safety. The use of sensors and IoT networks opens up the energy grid to cyber-attacks that can cause disruption to energy distribution flows and even to the distribution infrastructure itself. As energy is fundamental for all aspects of modern living (from cooking to heating to telecoms), such disruptions can directly affect people’s well-being.

To date, cyber-attacks on the energy grid have been sparse but raise significant concerns. In 2015, and again in 2016, hackers launched a cyber-attack on West Ukraine’s power grid.[15] The Industroyer malware hijacked standardized industrial communication protocols, which are used in most critical infrastructure systems, to take direct control of electricity substation switches and circuit breakers to cut electricity in 250,000 households in Western Ukraine for several hours.[16] Lying dormant until instructed otherwise, malware can be reactivated remotely to overwrite documents with random data or make the operating system unbootable. Cyber-attacks on the energy grid have economic implications for citizens at a national level; they have cost the U.K. 545 million euro in losses alone, while global losses were estimated to be 1.69 billion euro in 2018.[17]

Affordability and energy equity[e]: A new criteria to set society apart

One of the key drivers for the smartification[f] of energy grids is to create energy abundance, or at least sufficiency, without the need for costly infrastructure investments, in order to maintain energy affordability for all.[18] The introduction of smart grids and active demand systems that monitor and incentivize alternative energy consumption habits can enable dynamic consumption of energy by enabling customers to shift their consumption to take advantage of dynamic pricing.[18]

Industrial and commercial organizations have experts who work on optimizing energy requirements for their organizations. Citizens, however, lack the expertise, drive, and flexibility to change their lifestyles according to dynamic pricing. The same holds for most SMEs and their energy consumption patterns.[19] Energy aggregators and storage operators are expected to offer alternative services to facilitate dynamic consumption and manage the energy production of individual or community owned renewables. Nevertheless, smart energy systems will pose energy equity dilemmas around energy justice. For example, while the cost of the energy grid is funded via taxation and hence shared between citizens, the benefits from transition to smart grids are not equally shared. Affluent consumers (e.g., those who can afford electric cars or to invest in photo-voltaic energy production) will reap the benefits of smart grids earlier and to a larger extent. Smart grids also raise questions about the potential of algorithmic bias in managing energy distribution. For example, how can we ensure that energy distribution algorithms will not be designed to favor charging an affluent person’s electric car over the washing machine of a poorer family?

While smart grids are seen as one of the solutions to effecting energy justice or equity, what they in fact try to achieve is energy abundance, such that there is enough supply to satisfy the disproportionate increases in energy demand.[20] One could argue that via dynamic pricing, such technologies promote social engineering of the energy consumption patterns of large sections of the population for whom spending on energy consumption is a considerable part of their discretionary income, to support the ever-expanding list of electronic gadgets and (soon) electric vehicles available to the more affluent members of society.[21] Poorer socio-economic strata would be the most motivated to save on their energy costs, but they might find it difficult to benefit from dynamic pricing as their energy use is frugal to begin with. There is also a concern that dynamic pricing will leave consumers who are unable to shift their energy consumption worse off, as companies will try to "penalize" energy use during peak times by raising prices.[19]

Sustainability: Doing our bit for climate change

Smart grids are part of the E.U.’s green energy strategy to tackle CO2 emissions and climate change, in cost efficient ways. The more accurate and real-time the modelling that matches energy production with consumption can be, the more responsive the grid will be in managing electricity flows. Hence, the more reliably renewables can be incorporated into the energy production mix. The transition to sustainable energy resources is a key part of the climate change agenda and closely linked to issues of intergenerational justice. Another key contribution of smart grids towards the E.U.’s sustainability goals is the transition of transportation systems from fossil-fuels to electric. While this will exponentially increase the demand for electricity over the coming years, it enables greater freedom as to which sources this electricity will come from. On the other hand, smart meters and SIS technologies come at an energy cost, as they themselves use electricity to function. Hence, they contribute to a country’s overall energy consumption by the public sector as they become operational part of the energy distribution network, a critical infrastructure funded by taxation.

The case of a large Dutch distribution system operator using SIS in smart grids

Footnotes

- ↑ "The interconnection via the Internet of computing devices embedded in everyday objects, enabling them to send and receive data." Source

- ↑ "A system in which a record of transactions made in bitcoin or another cryptocurrency are maintained across several computers that are linked in a peer-to-peer network." Source. The term is now used for recording exchanges beyond cryptocurrency.

- ↑ Prosumer: “A prosumer is a person who consumes and produces a product. It is derived from "prosumption," a dot-com-era business term meaning "production by consumers." These terms were coined in 1980 by American futurist Alvin Toffler, and were widely used by many technology writers of the time. Today it generally refers to a person using commons-based peer production.” Source: Wikipedia.

- ↑ Interestingly, the company was acquired and is not part of C3 platform, now offering behavioral and AI data analytics platforms for smart grids and platforms. Source.

- ↑ Energy equity: An index that evaluates the accessibility and affordability of energy within a country or region, and one of the three core dimensions of the Energy Trilemma. Source.

- ↑ smartification (noun) : The process of transforming negative behavior into a smart personality. [from the root word smart]. Source

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 European Commission (17 June 2014). "Benchmarking smart metering deployment in the EU-27 with a focus on electricity". Publications Office of the European Union. https://ses.jrc.ec.europa.eu/publications/reports/benchmarking-smart-metering-deployment-eu-27-focus-electricity.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 European Commission (2016). "ransforming the European Energy System Through INNOVATION:Integrated SET Plan Progress in 2016". Publications Office of the European Union. doi:10.2833/661954. https://setis.ec.europa.eu/transforming-european-energy-system-through-innovation-2016.

- ↑ Ramchurn, S.D.; Vytelingum, P.; Rogers, A.; Jennings, N.R. (2012). "Putting the 'smarts' into the smart grid: A grand challenge for artificial intelligence". Communications of the ACM 55 (4): 86–97. doi:10.1145/2133806.2133825.

- ↑ Rathi, A. (8 April 2017). "The UK’s electrical grid is so overrun with renewable power, it may pay wind farms to stop producing it". Quartz. https://qz.com/952827/the-uks-electrical-grid-is-so-overrun-with-renewable-power-it-may-pay-wind-farms-to-stop-producing-it/. Retrieved 19 January 2019.

- ↑ Liang, X. (2017). "Emerging Power Quality Challenges Due to Integration of Renewable Energy Sources". IEEE Transactions on Industry Applications 53 (2): 855–866. doi:10.1109/TIA.2016.2626253.

- ↑ Rojin, R.K. (2013). "A Review of Power Quality Problems and Solutions in Electrical Power System". International Journal of Advanced Research in Electrical, Electronics and Instrumentation Engineering 2 (11): 5605–5614. http://www.rroij.com/open-access/a-review-of-power-qualityproblems-and-solutions-inelectrical-power-system.php?aid=42532.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Hübner, M. (September 2018). "Regulatory Innovation Zones for Smart Energy Networks". SlideShare. https://www.slideshare.net/sustenergy/regulatory-innovation-zones-for-smart-energy-networks.

- ↑ International Energy Agency (2017). "Digitization and Energy" (PDF). https://www.iea.org/publications/freepublications/publication/DigitalizationandEnergy3.pdf. Retrieved 25 January 2019.

- ↑ Weaver, K.T. (6 November 2014). "Dutch case study: “smart” meter privacy invasions are unjustifiable in a democratic society". Take Back Your Power. https://takebackyourpower.net/smart-meter-privacy-invasions-are-unjustifiable-in-a-democratic-society/. Retrieved 25 January 2019.

- ↑ International Agency for Research on Cancer (2013). "Non-Ionizing Radiation, Part 2: Radiofrequency Electromagnetic Fields" (PDF). World Health Organization. https://monographs.iarc.fr/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/mono102.pdf.

- ↑ Weaver, K.T. (18 August 2018). "Federal Court Rules against Consumers on Smart Meters and Privacy Rights". Smart Grid Awareness. https://smartgridawareness.org/2018/08/18/federal-court-rules-against-consumers-on-smart-meters/. Retrieved 25 January 2019.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 Gray, J. (24 May 2018). "Pricing and trust: A utilities conundrum". Utility Week. https://utilityweek.co.uk/pricing-trust-utilities-conundrum/. Retrieved 25 January 2019.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 Knapman, H. (30 January 2018). "Households pressured into getting smart meters". Moneywise. https://www.moneywise.co.uk/news/2018-01-30%E2%80%8C%E2%80%8C/households-pressured-getting-smart-meters. Retrieved 25 January 2019.

- ↑ Eder-Neuhauser, P.; Zseby, T.; Fabini, J. et al. (2017). "Cyber attack models for smart grid environments". Sustainable Energy, Grids and Networks 12: 10–29. doi:10.1016/j.segan.2017.08.002.

- ↑ Cherepanov, A. (3 January 2016). "BlackEnergy by the SSHBearDoor: Attacks against Ukrainian news media and electric industry". WeLiveSecurity. https://www.welivesecurity.com/2016/01/03/blackenergy-sshbeardoor-details-2015-attacks-ukrainian-news-media-electric-industry/. Retrieved 25 January 2019.

- ↑ Cherepanov, A.; Lipovsky, R. (12 June 2017). "Industroyer: Biggest threat to industrial control systems since Stuxnet". WeLiveSecurity. https://www.welivesecurity.com/2017/06/12/industroyer-biggest-threat-industrial-control-systems-since-stuxnet/. Retrieved 25 January 2019.

- ↑ Tofan, D.; Nikolakopoulos, T.; Darra, E. (August 2016). "The cost of incidents affecting CIIs: Systematic review of studies concerning the economic impact of cyber-security incidents on critical information infrastructures (CII)". European Union Agency for Network and Information Security. doi:10.2824/475621. https://www.enisa.europa.eu/publications/the-cost-of-incidents-affecting-ciis.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 Ricci, A.; Faberi, S.; Brizard, N. et al. (14 September 2012). "Smart Grids / Energy Grids - The Techno-Scientific Developments of Smart Grids and the Related Political, Societal and Economic Implications (Study and Options Brief)". European Parliament. https://www.europarl.europa.eu/stoa/en/document/IPOL-JOIN_ET(2012)488797. Retrieved 25 January 2019.

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 Faruqui, A. (30 March 2010). "The Ethics of Dynamic Pricing" (PDF). Grid Solar, LLC. http://gridsolar.com/smartgrid/docket2010-267/Attachment_11.pdf. Retrieved 25 January 2019.

- ↑ Sovacool, B.K.; Dworkin, M.H. (2015). "Energy justice: Conceptual insights and practical applications". Applied Energy 142: 435–44. doi:10.1016/j.apenergy.2015.01.002.

- ↑ McCauley, D.; Ramasar, V.; Heffron, R.J. et al. (2019). "Energy justice in the transition to low carbon energy systems: Exploring key themes in interdisciplinary research". Applied Energy 233–4: 916–21. doi:10.1016/j.apenergy.2018.10.005.

Notes

This presentation is faithful to the original, with only a few minor changes to presentation, grammar, and punctuation. In some cases important information was missing from the references, and that information was added. To more easily differentiate footnotes from references, the original footnotes (which where numbered) were updated to use lowercase letters. The original article has an inline citation for Servapali et al. 2012 but nothing listed in the sources for it. An educated guess was made concerning the source and was added for this version. The original article has an inline citation for ENSI, 2016 but nothing in the sources to match it. The source is presumably the 2018 "Regulatory Innovation Zones for Smart Energy Networks" presentation referenced in the description of Figure 3 and is used in this version for the citation. In the original, Footnote 3 is found inline in the text but is not expounded upon; it has been omitted for this version. The original has an inline citation for Eder-Neuhauser et al. 2017 but doesn't include the detailed citation in the references; the presumed reference has been added for this version.