Journal:Preferred names, preferred pronouns, and gender identity in the electronic medical record and laboratory information system: Is pathology ready?

| Full article title |

Preferred names, preferred pronouns, and gender identity in the electronic medical record and laboratory information system: Is pathology ready? |

|---|---|

| Journal | Journal of Pathology Informatics |

| Author(s) |

Imborek, Katherine L.; Nisly Nicole L.; Hesseltine, Michael J.; Grienke, Jana; Zikmund, Todd A.; Dreyer, Nicholas R.; Blau, John L.; Hightower, Maia; Humble, Robert M.; Krasowski, Matthew D. |

| Author affiliation(s) | University of Iowa Hospitals and Clinics |

| Primary contact | Email: Available w/ login |

| Year published | 2017 |

| Volume and issue | 8 |

| Page(s) | 42 |

| DOI | 10.4103/jpi.jpi_52_17 |

| ISSN | 2153-3539 |

| Distribution license | Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported |

| Website | http://www.jpathinformatics.org |

| Download | http://www.jpathinformatics.org/temp/JPatholInform8142-6286959_172749.pdf (PDF) |

Abstract

Background: Electronic medical records (EMRs) and laboratory information systems (LISs) commonly utilize patient identifiers such as legal name, sex, medical record number, and date of birth. There have been recommendations from some EMR working groups (e.g., the World Professional Association for Transgender Health) to include preferred name, pronoun preference, assigned sex at birth, and gender identity in the EMR. These practices are currently uncommon in the United States. There has been little published on the potential impact of these changes on pathology and LISs.

Methods: We review the available literature and guidelines on the use of preferred name and gender identity on pathology, including data on changes in laboratory testing following gender transition treatments. We also describe pathology and clinical laboratory challenges in the implementation of preferred name at our institution.

Results: Preferred name, pronoun preference, and gender identity have the most immediate impact on the areas of pathology with direct patient contact such as phlebotomy and transfusion medicine, both in terms of interaction with patients and policies for patient identification. Gender identity affects the regulation and policies within transfusion medicine, including blood donor risk assessment and eligibility. There are limited studies on the impact of gender transition treatments on laboratory tests, but multiple studies have demonstrated complex changes in chemistry and hematology tests. A broader challenge is that, even as EMRs add functionality, pathology computer systems (e.g., LIS, middleware, reference laboratory, and outreach interfaces) may not have functionality to store or display preferred name and gender identity.

Conclusions: Implementation of preferred name, pronoun preference, and gender identity presents multiple challenges and opportunities for pathology.

Keywords: clinical laboratory information system, electronic health records, gender dysphoria, medical informatics, transgender

Introduction

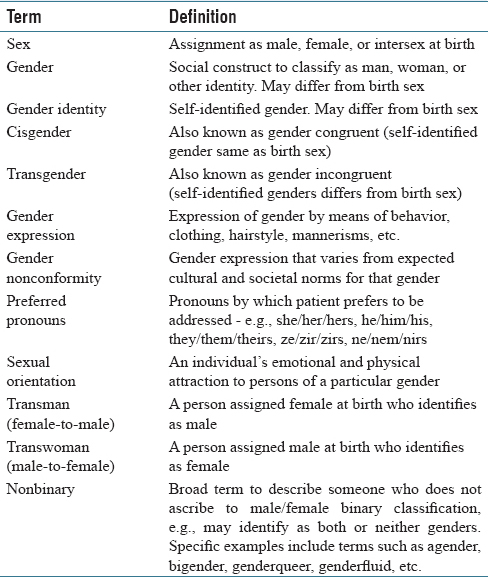

Electronic medical records (EMRs) and patient identification labels generally use patient legal name, date of birth, and a medical record number as key identifiers for patients.[1][2] Laboratory information systems (LISs) and middleware software also use these identifiers along with additional items such as accession and surgical pathology case numbers.[3] Although the legal name is most commonly used in EMRs, many patients have a “preferred name” that differs from their legal first name [Table 1]. The preferred name may be a nickname (e.g., “Bill” for “William”), use of a middle name, or some other name altogether. For transgender patients, the preferred name may match their affirmed gender and also be recognizable as of a different gender than the name assigned at birth.[4] The use of preferred name can have a positive customer service benefit in allowing for healthcare staff to address the patient in a manner chosen by the patient, whether or not they elect to provide a preferred name. The use of preferred name for transgender patients has been identified as important in providing inclusion toward a class of patients that have historically been disenfranchised from the healthcare system.[4][5][6][7][8][9]

|

Transgender is a term for individuals whose gender identity or expression does not align with their assigned birth sex and/or whose gender identity is outside of a binary (i.e., male/female) gender classification.[10][11] Cisgender refers to those whose gender identity or expression aligns with their assigned birth sex. Preferred pronoun refers to the pronouns that reflect a person's gender identity and expression (e.g., he/him/his for trans- or cis-gender males; she/her/hers for trans- or cis-gender females).[4][11] For people who do not ascribe to the male/female binary classification (“nonbinary”), nonbinary pronouns (ze/zir/zirs, hir/hirs, ne/nir/nirs, they/them/their) may be preferred. Transgender people can have their legal identity documents (e.g., passports, driver's license) changed to a different gender although laws vary in different countries and localities. Within the United States, there is significant variation in state laws in officially changing gender identity.[12][13] Even for those states that allow this, the requirements can vary (e.g., whether surgical reassignment is necessary or whether hormonal therapy alone may suffice). A detailed description of the process for one state (Iowa) is available online.[14] It is also important to keep in mind that gender identity and sexual orientation (emotional and physical attraction to persons of a particular gender) are distinct concepts.[10][11] For example, a transwoman may be attracted to men, women, or both genders. As will be discussed below, terminology related to gender identity and sexual orientation can be particularly confusing in the blood donor criteria setting.

References

- ↑ Lichtner, V.; Wilson, S.; Galliers, J.R. (2008). "The challenging nature of patient identifiers: An ethnographic study of patient identification at a London walk-in centre". Health Informatics Journal 14 (2): 141–50. doi:10.1177/1081180X08089321. PMID 18477600.

- ↑ McCoy, A.B.; Wright, A.; Kahn, M.G. (2013). "Matching identifiers in electronic health records: implications for duplicate records and patient safety". BMJ Quality & Safety 22 (3): 219–24. doi:10.1136/bmjqs-2012-001419. PMID 23362505.

- ↑ Pantanowitz, L.; Henricks, W.H.; Beckwith, B.A. (2007). "Medical laboratory informatics". Clinics in Laboratory Medicine 27 (4): 823–43. doi:10.1016/j.cll.2007.07.011. PMID 17950900.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 Deutsch, M.B.; Buchholz, D. (2015). "Electronic health records and transgender patients--Practical recommendations for the collection of gender identity data". Journal of General Internal Medicine 30 (6): 843–7. doi:10.1007/s11606-014-3148-7. PMC PMC4441683. PMID 25560316. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4441683.

- ↑ Donald, C.; Ehrenfeld, J.M. (2015). "The Opportunity for Medical Systems to Reduce Health Disparities Among Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender and Intersex Patients". Journal of Medical Systems 39 (11): 178. doi:10.1007/s10916-015-0355-7. PMID 26411930.

- ↑ Gridley, S.J.; Crouch, J.M.; Evans, Y. et al. (2016). "Youth and Caregiver Perspectives on Barriers to Gender-Affirming Health Care for Transgender Youth". Journal of Adolescent Health 59 (3): 254–61. doi:10.1016/j.jadohealth.2016.03.017. PMID 27235374.

- ↑ Winter, S.; Diamond, M.; Green, J. et al. (2016). "Transgender people: Health at the margins of society". Lancet 388 (10042): 390–400. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(16)00683-8. PMID 27323925.

- ↑ Wylie, K.; Knudson, G.; Khan, S.I. et al. (2016). "Serving transgender people: Clinical care considerations and service delivery models in transgender health". Lancet 388 (10042): 401–11. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(16)00682-6. PMID 27323926.

- ↑ Roberts, T.K.; Fantz, C.R. (2014). "Barriers to quality health care for the transgender population". Clinical Biochemistry 47 (10–11): 983–7. doi:10.1016/j.clinbiochem.2014.02.009. PMID 24560655.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Goldstein, Z.; Corneil, T.A.; Greene, D.N. (2017). "When Gender Identity Doesn't Equal Sex Recorded at Birth: The Role of the Laboratory in Providing Effective Healthcare to the Transgender Community". Clinical Chemistry 63 (8): 1342–1352. doi:10.1373/clinchem.2016.258780. PMID 28679645.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 Gupta, S.; Imborek, K.L.; Krasowski, M.D. (2016). "Challenges in Transgender Healthcare: The Pathology Perspective". Laboratory Medicine 47 (3): 180-8. doi:10.1093/labmed/lmw020. PMC PMC4985769. PMID 27287942. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4985769.

- ↑ "Transgender Law Center". Transgender Law Center. https://transgenderlawcenter.org/. Retrieved 28 July 2017.

- ↑ "Affirmative Care for Transgender and Gender Non-Conforming People: Best Practices for Front-line Health Care Staff" (PDF). The Fenway Institute. Fall 2016. https://www.lgbthealtheducation.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/12/Affirmative-Care-for-Transgender-and-Gender-Non-conforming-People-Best-Practices-for-Front-line-Health-Care-Staff.pdf. Retrieved 28 July 2017.

- ↑ Bigley, E.; Weiner, J.; Bermudez, B. et al. (1 February 2017). "The Iowa Guide to Changing Legal Identity Documents" (PDF). University of Iowa College of Law Clinical Law Programs. https://transequality.org/sites/default/files/docs/id/Iowa%20Guide%20to%20Changing%20Legal%20Identity%20Documents%20February%203%202017.pdf. Retrieved 28 July 2017.

Notes

This presentation is faithful to the original, with only a few minor changes to presentation and updates to spelling and grammar. In some cases important information was missing from the references, and that information was added.