Journal:Assessment of and response to data needs of clinical and translational science researchers and beyond

| Full article title | Assessment of and response to data needs of clinical and translational science researchers and beyond |

|---|---|

| Journal | Journal of eScience Librarianship |

| Author(s) | Norton, Hannah F.; Tennant, Michele R.; Botero, Cecilia; Garcia-Milian, Rolando |

| Author affiliation(s) | University of Florida, Yale University |

| Primary contact | Email: nortonh at ufl dot edu |

| Year published | 2016 |

| Volume and issue | 5 (1) |

| Page(s) | e1090 |

| DOI | 10.7191/jeslib.2016.1090 |

| ISSN | 2161-3974 |

| Distribution license | Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International |

| Website | http://escholarship.umassmed.edu/jeslib/vol5/iss1/2/ |

| Download | http://escholarship.umassmed.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1090&context=jeslib (PDF) |

|

|

This article should not be considered complete until this message box has been removed. This is a work in progress. |

Abstract

Objective and setting: As universities and libraries grapple with data management and “big data,” the need for data management solutions across disciplines is particularly relevant in clinical and translational science research, which is designed to traverse disciplinary and institutional boundaries. At the University of Florida Health Science Center Library, a team of librarians undertook an assessment of the research data management needs of clinical and translation science (CTS) researchers, including an online assessment and follow-up one-on-one interviews.

Design and Methods: The 20-question online assessment was distributed to all investigators affiliated with UF’s Clinical and Translational Science Institute (CTSI) and 59 investigators responded. Follow-up in-depth interviews were conducted with nine faculty and staff members.

Results: Results indicate that UF’s CTS researchers have diverse data management needs that are often specific to their discipline or current research project and span the data lifecycle. A common theme in responses was the need for consistent data management training, particularly for graduate students; this led to localized training within the Health Science Center and CTSI, as well as campus-wide training. Another campus-wide outcome was the creation of an action-oriented Data Management/Curation Task Force, led by the libraries and with participation from Research Computing and the Office of Research.

Conclusions: Initiating conversations with affected stakeholders and campus leadership about best practices in data management and implications for institutional policy shows the library’s proactive leadership and furthers our goal to provide concrete guidance to our users in this area.

Keywords: needs assessment, clinical and translational science, service development

Objective and settings

Biomedical researchers work with considerable amounts of heterogeneous data; managing these datasets raises new challenges in terms of acquiring, archiving, annotating, and analyzing data. Libraries across the nation and the world are developing tools to manage this research data, extending natural skills within libraries for organizing, sharing, and archiving information, as well as educating staff about best practices. This stems largely from an increased interest in data management and data sharing at the researcher level, fueled by both funders’ inclusion of data management plan requirements in proposals and by collaborative, large-scale research projects that generate data that is “big” and diverse.[1] The need for data management solutions across disciplines is particularly relevant in clinical and translational science (CTS) research, which is designed to cut across disciplinary and institutional boundaries. Data sharing, organization, storage, and security must scale up to meet these growing needs.

A number of roles in data management and curation have been proposed for librarians including, among others: hosting institutional and disciplinary repositories, developing data publication standards, supporting documentation and metadata use, training researchers and students in funders’ requirements and best practices in data management, working more directly with offices of research, deploying existing tools, hosting data management events (symposia, reflective workshops), embedding into research laboratories to provide data management solutions, and advocating for data sharing.[2][3][4][5][6][7][8][9][10][11][12] Reznick-Zellen et al.[13] postulate three “tiers” of library-based data management services: education (for example, LibGuides, webpages, and workshops), consultation (on data management plans, metadata standards, repository deposition, etc.), and infrastructure (data staging platforms and repositories).

With limited resources available, an integral step to developing these new services is identifying specific needs of the patrons to whom these services are targeted and ensuring that time and resources go into services that truly map to those needs. Needs assessments can also illuminate issues outside of the scope of direct library services, but for which librarians can be advocates on the institutional level. Although the importance of needs assessment is widely agreed upon[14] and a number of libraries have performed such assessments of data management needs[15][16][17][18][19][8][11][20], a 2009 survey of ARL institutions indicated that 62% of responding institutions had not performed a data needs assessment although 73% of libraries had some involvement in e-Science at their institution.[21]

Beginning in 2006, the National Institutes of Health (NIH) began offering Clinical and Translational Science Awards (CTSAs) to institutions across the country in order to minimize the time from discovery to clinical practice, enhance community-engagement in clinical research, and train new clinical and translational science researchers.[22] In 2009, the University of Florida (UF) received CTSA funding for its existing Clinical and Translational Science Institute (CTSI). As of 2015, the CTSI’s reach has expanded to more than 1,800 investigators across the University’s 16 colleges using CTSI services.[23]

The UF Health Science Center Library (HSCL) serves the six colleges of UF’s Academic Health Center (Dentistry, Medicine, Nursing, Pharmacy, Public Health and Health Professions, and Veterinary Medicine) and related centers and institutes, including the CTSI. HSCL is part of the broader campus library system, the George A. Smathers Libraries. At HSCL, dual interests in campus researchers’ data management needs and those particular to the CTSI led a team of librarians to undertake an assessment of the research data management needs of CTS researchers, including an online assessment and follow-up, one-on-one interviews. This assessment was situated within a broader project funded by the National Network of Libraries of Medicine, Southeast Atlantic Region focused on assessing CTS researcher needs: general information needs, bioinformatics needs, and data needs. Given the diversity of CTS researchers and the centrality of data to their research, HSCL librarians identified CTSI-affiliated researchers as an ideal pilot group to use for campus data needs assessments. At the same time, HSCL librarians developed a strong partnership with the Director of UF’s High Performance Computing Center (now known as Research Computing), who values the library’s role in data endeavors. He joined two of the Smathers Libraries’ Associate Deans (including author CB) in participating in the ARL E-Science Institute in 2011 and performing a campus environmental scan related to e-science and data services focused primarily on the plans and attitudes of high-level administrators. Additional suggestions for service development were gathered when three of the authors (CB, MRT, HFN) used funding awarded through UF’s Faculty Enhancement Opportunity program (mini-sabbaticals) to visit Purdue University’s library and learn from its successful data program.

Design and methods

The authors conducted a multimodal needs assessment using a combination of an online survey and in-depth, one-on-one semi-structured interviews. Semi-structured interviews were selected as a complementary means of data collection because they are well suited for exploring respondents’ perceptions and opinions on complex issues. In addition, they enable asking for more information and clarification of answers.[24] In order to ensure the safety of study participants and confidentiality of their data, both the survey and the subsequent interviews were approved by the University of Florida Institutional Review Board (Exemption #U-1142-2011).

Survey

In the spring of 2012, a team of three HSCL librarians distributed a 20-question online assessment (see Appendix 1) to all investigators affiliated with UF’s Clinical and Translational Science Institute, a total of 834 individuals. Questions were developed in collaboration with the director of UF’s High Performance Computing Center and colleagues in the main campus library’s Digital Library Center.

Interviews

In order to obtain more in-depth information from a subset of individuals across the CTSI, three HSCL librarians conducted interviews with CTSI-affiliated faculty or staff. The full list of CTSI-affiliated researchers was reviewed by librarian team members, and 58 individuals were identified who had worked closely with the libraries in the past and represented diverse disciplines; these individuals were contacted about participating in interviews. Nine individuals from this list agreed to be interviewed. Each interview lasted 30-60 minutes and was audio-recorded for later transcription and qualitative coding into themes; all interviews were conducted by two librarians (with one exception in which only one librarian conducted the interview). The interviews were organized around a series of questions modified from the University of Virginia Libraries’ data interview template, which itself is modified from Purdue’s Data Curation Profile interview template.[16] These questions addressed the broad topics of research area, data types, how data is worked with, preservation concerns, sharing and long-term accessibility, and what assistance from the library or other campus entities would make data management easier (see Appendix 2). The interview format was flexible enough that participants were able to address any arising concerns or comments about data management that did not fit into these categories. The invitation to participate in interviews and the in-person introduction on the day of the interview stressed that the interview was part of a broad needs assessment regarding data management and that any related concerns or barriers could be discussed. All of the authors sequentially reviewed the interview transcripts, identified relevant quotes, and coded them using 21 themes (e.g. sharing, backups, lab notebooks, etc.).

Results

Survey

Fifty-nine investigators responded to the survey, for a response rate of 7.1 percent. Survey respondents represented nine of UF’s 16 colleges, with a majority of responses coming from five of the six Health Science Center colleges served directly by the HSCL: Medicine (59.3 percent), Public Health & Health Professions (9.3 percent), Dentistry (7.4 percent), Pharmacy (5.6 percent), and Veterinary Medicine (1.9 percent). Other colleges represented were Agriculture and Life Sciences (7.4 percent), Liberal Arts & Sciences (3.7 percent), and Journalism (1.9 percent). The vast majority of respondents were faculty members (93.2 percent); the remainder were graduate students (3.4 percent), postdocs (1.7 percent), and staff (1.7 percent).

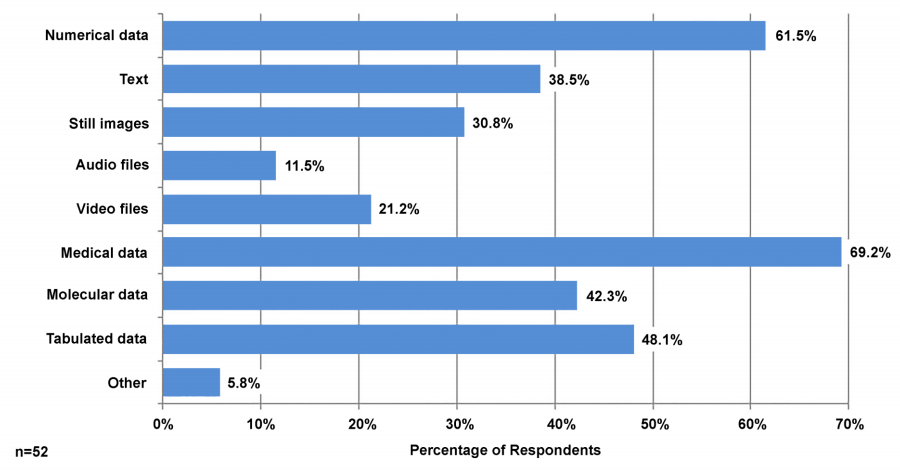

Figure 1 shows the types of data that survey respondents said they generate. Respondents could choose as many data types as were relevant to them, and on average they listed at least three types of data. The most commonly chosen types of data were medical (69.2 percent), numerical (61.5 percent), tabulated (48.1 percent), molecular (42.3 percent), and text data (38.5 percent). Mentioned under “other data” were qualitative data, performance data, and MRI images.

Participants were asked to list the formats in which their data exist (what file formats or file extensions they use); this open-text question had a lower response than the multiple-choice questions (n=29). The overwhelming majority of respondents use spreadsheets (82.8 percent). Other frequently mentioned file formats were those for specific statistical software (34.5 percent), word processing documents (27.6 percent), images (24.1 percent), databases (20.7 percent), and other file formats (24.1 percent) followed by video (13.8 percent) and text (6.9 percent). Other formats listed included audio, code, survey responses, and PowerPoint. This frequent use of non-specific applications such as spreadsheets and word processing documents mirrors results elsewhere in the literature.[15]

|

References

- ↑ National Science Board (September 2005). "Long-Lived Digital Data Collections Enabling Research and Education in the 21st Century". National Science Foundation. pp. 89. http://www.nsf.gov/pubs/2005/nsb0540/.

- ↑ Gold, A. (2007). "Cyberinfrastructure, Data, and Libraries, Part 2: Libraries and the Data Challenge: Roles and Actions for Libraries". D-Lib Magazine 13. doi:10.1045/july20september-gold-pt2.

- ↑ Charbonneau, D.H. (2013). "Strategies for Data Management Engagement". Medical Reference Services Quarterly 32 (3): 365-74. doi:10.1080/02763869.2013.807089. PMID 23869641.

- ↑ Garritano, J.R.; Carlson, J.R. (2009). "A Subject Librarian's Guide to Collaborating on e-Science Projects". Issues in Science and Technology Librarianship 57 (Spring 2009). doi:10.5062/F42B8VZ3.

- ↑ Heidorn, P.B. (2011). "The Emerging Role of Libraries in Data Curation and E-science". Journal of Library Administration 51 (7–8): 662–672. doi:10.1080/01930826.2011.601269.

- ↑ Rambo, N. (2009). "E-science and biomedical libraries". Journal of the Medical Library Association 97 (3): 159–161. doi:10.3163/1536-5050.97.3.001. PMC PMC2706433. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2706433.

- ↑ Reed, R.B. (2015). "Diving into Data: Planning a Research Data Management Event". Journal of eScience Librarianship 4 (1): e1071. doi:10.7191/jeslib.2015.1071.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Peters, C.; Vaughn, P. (2014). "Initiating Data Management Instruction to Graduate Students at the University of Houston Using the New England Collaborative Data Management Curriculum". Journal of eScience Librarianship 3 (1): e1064. doi:10.7191/jeslib.2014.1064.

- ↑ Goldman, J.; Kafel, D.; Martin, E.R. (2015). "Assessment of Data Management Services at New England Region Resource Libraries". Journal of eScience Librarianship 4 (1): e1068. doi:10.7191/jeslib.2015.1068.

- ↑ Piorun, M.E.; Kafel, D.; Leger-Hornby, T. et al. (2012). "Teaching Research Data Management: An Undergraduate/Graduate Curriculum". Journal of eScience Librarianship 1 (1): e1003. doi:10.7191/jeslib.2012.1003.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 Rambo, Neil (22 October 2015). "Research Data Management Roles for Libraries" (PDF). http://www.sr.ithaka.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/10/SR-Issue_Brief_Research_Data_Management_1022151.pdf.

- ↑ Nelson, M.S. (2015). "Data Management Outreach to Junior Faculty Members: A Case Study". Journal of eScience Librarianship 4 (1): e1076. doi:10.7191/jeslib.2015.1076.

- ↑ Reznik-Zellen, R.C.; Adamick, J.; McGinty, S. (2012). "Tiers of Research Data Support Services". Journal of eScience Librarianship 1 (1): e1002. doi:10.7191/jeslib.2012.1002.

- ↑ Foster, N.F.; Gibbons, S., ed. (2007) (PDF). Studying Students: The Undergraduate Research Project at the University of Rochester. Chicago: Association of College and Research Libraries. pp. 90. ISBN 9780838984376. http://www.ala.org/acrl/sites/ala.org.acrl/files/content/publications/booksanddigitalresources/digital/Foster-Gibbons_cmpd.pdf.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 Anderson, N.R.; Lee, S.; Brockenbrough, J.S. et al. (2007). "Issues in Biomedical Research Data Management and Analysis: Needs and Barriers". JAMIA 14 (4): 478–488. doi:10.1197/jamia.M2114. PMC PMC2244904. PMID 17460139. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2244904.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 Witt, M.; Carlson, J.; Brandt, D.S.; Cragin, M.H. (2009). "Constructing Data Curation Profiles". International Journal of Digital Curation 4 (3): 93–103. doi:10.2218/ijdc.v4i3.117.

- ↑ Bardyn, T.P.; Resnick, T.; Camina, S.K. (2012). "Translational Researchers’ Perceptions of Data Management Practices and Data Curation Needs: Findings from a Focus Group in an Academic Health Sciences Library". Journal of Web Librarianship 6 (4): 274–287. doi:10.1080/19322909.2012.730375.

- ↑ Reich, M.; Shipman, J.P.; Narus, S.P. et al. (2013). "Assessing clinical researchers' information needs to create responsive portals and tools: My Research Assistant (MyRA) at the University of Utah: A case study". Journal of the Medical Library Association 101 (1): 4–11. doi:10.3163/1536-5050.101.1.002. PMC PMC3543136. PMID 23405041. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3543136.

- ↑ Guindon, A. (2014). "Research Data Management at Concordia University: A Survey of Current Practices" (PDF). Feliciter 60 (2): 15–17. http://cla.ca/wp-content/uploads/60_2.pdf.

- ↑ Weller, T.; Monroe-Gulick, A. (2015). "Differences in the Data Practices, Challenges, and Future Needs of Graduate Students and Faculty Members". Journal of eScience Librarianship 4 (1): e1070. doi:10.7191/jeslib.2015.1070.

- ↑ Soehner, C.; Steeves, C.; Ward, J. (23 June 2010). "e-Science and data support services: a survey of ARL members". 31st Annual IATUL Conference. Purdue University. http://docs.lib.purdue.edu/iatul2010/conf/day3/1/.

- ↑ National Center for Research Resources (2009). "Clinical and Translational Science Awards: Advancing Scientific Discoveries Nationwide to Improve Health" (PDF). National Institutes of Health. pp. 37. https://ncats.nih.gov/files/CTSA-report-2006-2008.pdf.

- ↑ Guzick, D.S. (8 October 2015). "Clinical, Translational and Implementation Science: Part 1 - CTSA renewal". UFHealth. University of Florida. https://ufhealth.org/news/2015/clinical-translational-and-implementation-science-part-1-ctsa-renewal.

- ↑ Barribal, K.L.; While, A. (1994). "Collecting data using a semi-structured interview: A discussion paper". Journal of Advanced Nursing 19 (2): 328–335. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2648.1994.tb01088.x. PMID 8188965.

Notes

This presentation is faithful to the original, with only a few minor changes to presentation. In some cases important information was missing from the references, and that information was added. References were originally listed alphabetically; they were converted to the standard wiki inline format, in order of appearance.