Journal:Preferred names, preferred pronouns, and gender identity in the electronic medical record and laboratory information system: Is pathology ready?

| Full article title |

Preferred names, preferred pronouns, and gender identity in the electronic medical record and laboratory information system: Is pathology ready? |

|---|---|

| Journal | Journal of Pathology Informatics |

| Author(s) |

Imborek, Katherine L.; Nisly Nicole L.; Hesseltine, Michael J.; Grienke, Jana; Zikmund, Todd A.; Dreyer, Nicholas R.; Blau, John L.; Hightower, Maia; Humble, Robert M.; Krasowski, Matthew D. |

| Author affiliation(s) | University of Iowa Hospitals and Clinics |

| Primary contact | Email: Available w/ login |

| Year published | 2017 |

| Volume and issue | 8 |

| Page(s) | 42 |

| DOI | 10.4103/jpi.jpi_52_17 |

| ISSN | 2153-3539 |

| Distribution license | Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported |

| Website | http://www.jpathinformatics.org |

| Download | http://www.jpathinformatics.org/temp/JPatholInform8142-6286959_172749.pdf (PDF) |

|

|

This article should not be considered complete until this message box has been removed. This is a work in progress. |

Abstract

Background: Electronic medical records (EMRs) and laboratory information systems (LISs) commonly utilize patient identifiers such as legal name, sex, medical record number, and date of birth. There have been recommendations from some EMR working groups (e.g., the World Professional Association for Transgender Health) to include preferred name, pronoun preference, assigned sex at birth, and gender identity in the EMR. These practices are currently uncommon in the United States. There has been little published on the potential impact of these changes on pathology and LISs.

Methods: We review the available literature and guidelines on the use of preferred name and gender identity on pathology, including data on changes in laboratory testing following gender transition treatments. We also describe pathology and clinical laboratory challenges in the implementation of preferred name at our institution.

Results: Preferred name, pronoun preference, and gender identity have the most immediate impact on the areas of pathology with direct patient contact such as phlebotomy and transfusion medicine, both in terms of interaction with patients and policies for patient identification. Gender identity affects the regulation and policies within transfusion medicine, including blood donor risk assessment and eligibility. There are limited studies on the impact of gender transition treatments on laboratory tests, but multiple studies have demonstrated complex changes in chemistry and hematology tests. A broader challenge is that, even as EMRs add functionality, pathology computer systems (e.g., LIS, middleware, reference laboratory, and outreach interfaces) may not have functionality to store or display preferred name and gender identity.

Conclusions: Implementation of preferred name, pronoun preference, and gender identity presents multiple challenges and opportunities for pathology.

Keywords: clinical laboratory information system, electronic health records, gender dysphoria, medical informatics, transgender

Introduction

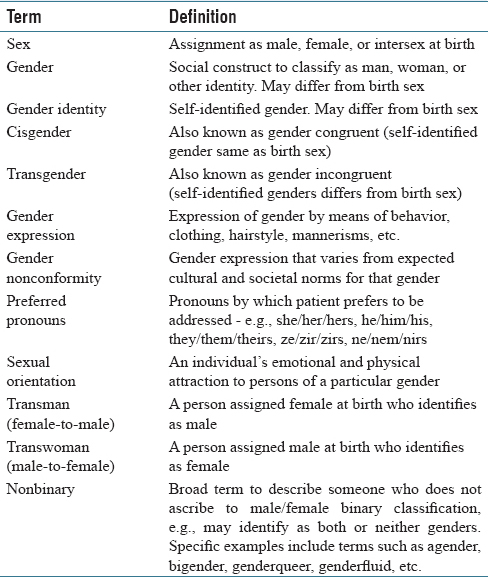

Electronic medical records (EMRs) and patient identification labels generally use patient legal name, date of birth, and a medical record number as key identifiers for patients.[1][2] Laboratory information systems (LISs) and middleware software also use these identifiers along with additional items such as accession and surgical pathology case numbers.[3] Although the legal name is most commonly used in EMRs, many patients have a “preferred name” that differs from their legal first name [Table 1]. The preferred name may be a nickname (e.g., “Bill” for “William”), use of a middle name, or some other name altogether. For transgender patients, the preferred name may match their affirmed gender and also be recognizable as of a different gender than the name assigned at birth.[4] The use of preferred name can have a positive customer service benefit in allowing for healthcare staff to address the patient in a manner chosen by the patient, whether or not they elect to provide a preferred name. The use of preferred name for transgender patients has been identified as important in providing inclusion toward a class of patients that have historically been disenfranchised from the healthcare system.[4][5][6][7][8][9]

|

Transgender is a term for individuals whose gender identity or expression does not align with their assigned birth sex and/or whose gender identity is outside of a binary (i.e., male/female) gender classification.[10][11] Cisgender refers to those whose gender identity or expression aligns with their assigned birth sex. Preferred pronoun refers to the pronouns that reflect a person's gender identity and expression (e.g., he/him/his for trans- or cis-gender males; she/her/hers for trans- or cis-gender females).[4][11] For people who do not ascribe to the male/female binary classification (“nonbinary”), nonbinary pronouns (ze/zir/zirs, hir/hirs, ne/nir/nirs, they/them/their) may be preferred. Transgender people can have their legal identity documents (e.g., passports, driver's license) changed to a different gender although laws vary in different countries and localities. Within the United States, there is significant variation in state laws in officially changing gender identity.[12][13] Even for those states that allow this, the requirements can vary (e.g., whether surgical reassignment is necessary or whether hormonal therapy alone may suffice). A detailed description of the process for one state (Iowa) is available online.[14] It is also important to keep in mind that gender identity and sexual orientation (emotional and physical attraction to persons of a particular gender) are distinct concepts.[10][11] For example, a transwoman may be attracted to men, women, or both genders. As will be discussed below, terminology related to gender identity and sexual orientation can be particularly confusing in the blood donor criteria setting.

Although preferred name, pronoun preference, and gender identity might have a minor impact for some patients, use of these has been identified as an important step in providing inclusive care for transgender patients.[4][5][9][11][15][16][17][18][19][20] Final rules issued by the Office of the National Coordinator for Health Information Technology (ONC) and the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) in October 2015 require EMR software certified for meaningful use to include fields for gender identity and sexual orientation.[15] An EMR working group from the World Professional Association for Transgender Health recommended that the basic demographic variables of an EMR include preferred name, gender identity, and pronoun preference as identified by patients.[21]

Although the inclusion of preferred name into the EMR and LIS clinical workflow might seem to be relatively straightforward, there are a number of potential complications. For example, there may be regulations for certain hospital practices that require the use of full legal name and where a preferred name is not an acceptable identifier. In addition, while an EMR may have functionality for a preferred name field, other informatics systems that transmit data into the EMR (e.g., pathology, pharmacy, and radiology) may not have this functionality. The use of preferred name especially impacts staff that has direct patient contact, including phlebotomists and schedulers within pathology. An excellent resource by the National LGBT Health Education Center details best practices for front line healthcare staff for the transgender and gender nonconforming patient population.[13]

In this report, we discuss pathology-related informatics challenges with preferred name, pronoun preference, and gender identity. We encountered some of these issues during the implementation of preferred name at the University of Iowa Hospitals and Clinics (UIHC), a state academic medical center. We present a detailed description of the overall preferred name project elsewhere but here focus on the pathology-specific issues. As more institutions incorporate preferred name, pronoun preference, and gender identity into the EMR, clinical laboratories and pathology practices will encounter these issues more often.

Preferred name implementation: Lessons learned at University of Iowa

Institutional details

The institution of this study, UIHC, is a 734-bed state academic medical center that includes pediatric and adult inpatient units, multiple intensive care units, emergency room with level one trauma capability, and outpatient services. UIHC has a multidisciplinary lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer, and questioning (LGBTQ) clinic staffed by providers well versed in the specific needs of LGBTQ patients. UIHC has been recognized as a Healthcare Equality Index national leader by the Human Rights Campaign since 2013 because of its institutional commitment to LGBTQ equality and inclusion.[22] The EMR throughout the UIHC healthcare system has been Epic (EpicCare Inpatient and EpicCare Ambulatory, Madison, WI, USA) since 2009. The LIS for all clinical laboratories is Epic Beaker, with Beaker Clinical Pathology (CP) implemented in 2014[23] and Beaker Anatomic Pathology in 2015. Middleware software (Instrument Manager, Data Innovations, Burlington, VT, USA) is used throughout the clinical laboratories for interfacing of laboratory instruments to the LIS.[24] The LIS for the UIHC DeGowin Blood Center is software from Haemonetics (Braintree, MA, USA).

References

- ↑ Lichtner, V.; Wilson, S.; Galliers, J.R. (2008). "The challenging nature of patient identifiers: An ethnographic study of patient identification at a London walk-in centre". Health Informatics Journal 14 (2): 141–50. doi:10.1177/1081180X08089321. PMID 18477600.

- ↑ McCoy, A.B.; Wright, A.; Kahn, M.G. (2013). "Matching identifiers in electronic health records: implications for duplicate records and patient safety". BMJ Quality & Safety 22 (3): 219–24. doi:10.1136/bmjqs-2012-001419. PMID 23362505.

- ↑ Pantanowitz, L.; Henricks, W.H.; Beckwith, B.A. (2007). "Medical laboratory informatics". Clinics in Laboratory Medicine 27 (4): 823–43. doi:10.1016/j.cll.2007.07.011. PMID 17950900.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 Deutsch, M.B.; Buchholz, D. (2015). "Electronic health records and transgender patients--Practical recommendations for the collection of gender identity data". Journal of General Internal Medicine 30 (6): 843–7. doi:10.1007/s11606-014-3148-7. PMC PMC4441683. PMID 25560316. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4441683.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Donald, C.; Ehrenfeld, J.M. (2015). "The Opportunity for Medical Systems to Reduce Health Disparities Among Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender and Intersex Patients". Journal of Medical Systems 39 (11): 178. doi:10.1007/s10916-015-0355-7. PMID 26411930.

- ↑ Gridley, S.J.; Crouch, J.M.; Evans, Y. et al. (2016). "Youth and Caregiver Perspectives on Barriers to Gender-Affirming Health Care for Transgender Youth". Journal of Adolescent Health 59 (3): 254–61. doi:10.1016/j.jadohealth.2016.03.017. PMID 27235374.

- ↑ Winter, S.; Diamond, M.; Green, J. et al. (2016). "Transgender people: Health at the margins of society". Lancet 388 (10042): 390–400. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(16)00683-8. PMID 27323925.

- ↑ Wylie, K.; Knudson, G.; Khan, S.I. et al. (2016). "Serving transgender people: Clinical care considerations and service delivery models in transgender health". Lancet 388 (10042): 401–11. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(16)00682-6. PMID 27323926.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Roberts, T.K.; Fantz, C.R. (2014). "Barriers to quality health care for the transgender population". Clinical Biochemistry 47 (10–11): 983–7. doi:10.1016/j.clinbiochem.2014.02.009. PMID 24560655.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Goldstein, Z.; Corneil, T.A.; Greene, D.N. (2017). "When Gender Identity Doesn't Equal Sex Recorded at Birth: The Role of the Laboratory in Providing Effective Healthcare to the Transgender Community". Clinical Chemistry 63 (8): 1342–1352. doi:10.1373/clinchem.2016.258780. PMID 28679645.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 11.3 Gupta, S.; Imborek, K.L.; Krasowski, M.D. (2016). "Challenges in Transgender Healthcare: The Pathology Perspective". Laboratory Medicine 47 (3): 180-8. doi:10.1093/labmed/lmw020. PMC PMC4985769. PMID 27287942. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4985769.

- ↑ "Transgender Law Center". Transgender Law Center. https://transgenderlawcenter.org/. Retrieved 28 July 2017.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 "Affirmative Care for Transgender and Gender Non-Conforming People: Best Practices for Front-line Health Care Staff" (PDF). The Fenway Institute. Fall 2016. https://www.lgbthealtheducation.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/12/Affirmative-Care-for-Transgender-and-Gender-Non-conforming-People-Best-Practices-for-Front-line-Health-Care-Staff.pdf. Retrieved 28 July 2017.

- ↑ Bigley, E.; Weiner, J.; Bermudez, B. et al. (1 February 2017). "The Iowa Guide to Changing Legal Identity Documents" (PDF). University of Iowa College of Law Clinical Law Programs. https://transequality.org/sites/default/files/docs/id/Iowa%20Guide%20to%20Changing%20Legal%20Identity%20Documents%20February%203%202017.pdf. Retrieved 28 July 2017.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 Cahill, S.R.; Baker, K.; Deutsch, M.B. et al. (2016). "Inclusion of Sexual Orientation and Gender Identity in Stage 3 Meaningful Use Guidelines: A Huge Step Forward for LGBT Health". LGBT Health 3 (2): 100–2. doi:10.1089/lgbt.2015.0136. PMID 26698386.

- ↑ Deutsch, M.B.; Keatley, J.; Sevelius, J.; Shade, S.B. (2014). "Collection of gender identity data using electronic medical records: survey of current end-user practices". Journal of the Association of Nurses in AIDS Care 25 (6): 657–63. doi:10.1016/j.jana.2014.04.001. PMID 24880490.

- ↑ MacCarthy, S.; Reisner, S.L.; Nunn, A. et al. (2015). "The Time Is Now: Attention Increases to Transgender Health in the United States but Scientific Knowledge Gaps Remain". LGBT Health 2 (4): 287–91. doi:10.1089/lgbt.2014.0073. PMC PMC4716649. PMID 26788768. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4716649.

- ↑ Callahan, E.J. (2015). "Opening the door to transgender care". Journal of General Internal Medicine 30 (6): 706–7. doi:10.1007/s11606-015-3255-0. PMC PMC4441676. PMID 25743431. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4441676.

- ↑ Callahan, E.J.; Sitkin, N.; Ton, H. et al. (2015). "Introducing sexual orientation and gender identity into the electronic health record: One academic health center's experience". Academic Medicine 90 (2): 154–60. doi:10.1097/ACM.0000000000000467. PMID 25162618.

- ↑ Unger, C.A. (2014). "Care of the transgender patient: The role of the gynecologist". American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology 210 (1): 16–26. doi:10.1016/j.ajog.2013.05.035. PMID 23707806.

- ↑ Deutsch, M.B.; Green, J.; Keatley, J. et al. (2013). "Electronic medical records and the transgender patient: Recommendations from the World Professional Association for Transgender Health EMR Working Group". JAMIA 20 (4): 700–3. doi:10.1136/amiajnl-2012-001472. PMC PMC3721165. PMID 23631835. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3721165.

- ↑ "Human Rights Campaign Foundation. Healthcare Equality Index 2016: Promoting Equitable and Inclusive Care for Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual and Transgender Patients and Their Families" (PDF). Human Rights Campaign Foundation. 2016. ISBN 9781934765364. https://assets2.hrc.org/files/assets/resources/HEI_2016_FINAL.pdf. Retrieved 28 July 2017.

- ↑ Krasowski, M.D.; Wilford, J.D.; Howard, W. et al. (2016). "Implementation of Epic Beaker Clinical Pathology at an academic medical center". Journal of Pathology Informatics 7: 7. doi:10.4103/2153-3539.175798. PMC PMC4763507. PMID 26955505. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4763507.

- ↑ Krasowski, M.D.; Davis, S.R.; Drees, D. et al. (2014). "Autoverification in a core clinical chemistry laboratory at an academic medical center". Journal of Pathology Informatics 5 (1): 13. doi:10.4103/2153-3539.129450. PMC PMC4023033. PMID 24843824. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4023033.

Notes

This presentation is faithful to the original, with only a few minor changes to presentation and updates to spelling and grammar. In some cases important information was missing from the references, and that information was added.