Difference between revisions of "User:Shawndouglas/sandbox/sublevel1"

Shawndouglas (talk | contribs) |

Shawndouglas (talk | contribs) |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

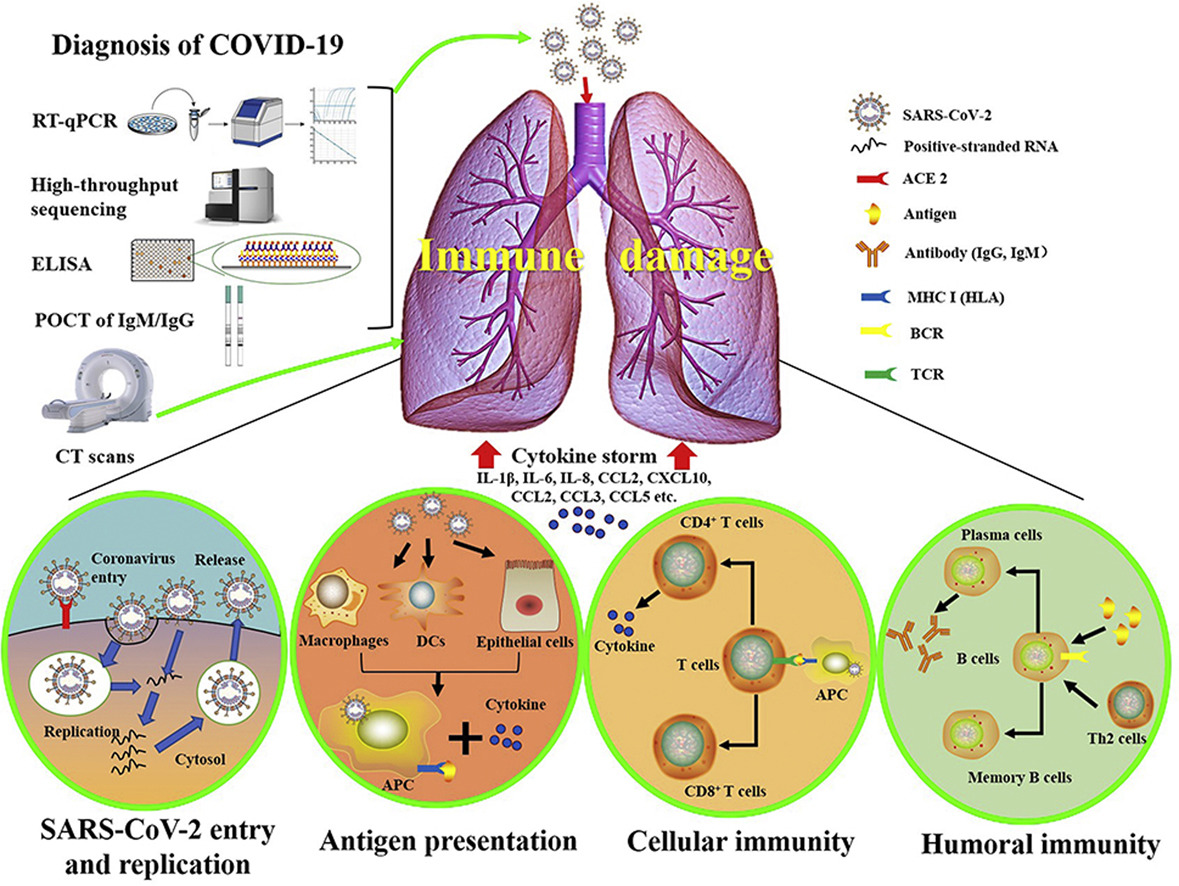

[[File:Fig1 Li JofPharmAnal2020 10-2.jpg|right|thumb|650px|The graphical abstract from [https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpha.2020.03.001 Li ''et al.'' 2020], showing general features of SARS-CoV-2, current knowledge of molecular immune pathogenesis, and diagnosis methods of COVID-19 based on present understanding of SARS-CoV and MERS-CoV viral infections]]COVID-19 has presented numerous societal challenges, from supply line interruptions and economic sagging to overwhelmed healthcare systems and civil disorder. However, these are largely the social, economic, and political ripple effects of a disease that has brought with it a set of inherent attributes that make it more difficult to manage in human populations than say the flu. | |||

However, COVID-19 is not the flu, and it is indeed worse in its effects than the flu, contrary to many people's perceptions. Yes, COVID-19 and the flu have some symptom overlap. Yes, COVID-19 and the flu have some transmission type overlap. But from there it diverges. COVID-19 and SARS-CoV-2 is different in that it is more prone to be transmitted to others during the presymptomatic phase. And the body of evidence has grown since early on in the pandemic<ref name="AchenbachStudies20">{{cite web |url=https://www.washingtonpost.com/health/2020/04/29/studies-leave-question-airborne-coronavirus-transmission-unanswered/ |title=Studies leave question of ‘airborne’ coronavirus transmission unanswered |author=Achenach, J.; Johnson, C.Y. |work=The Washington Post |date=29 April 2020 |accessdate=01 May 2020}}</ref> that SARS-CoV-2 is transmittable predominately via an airborne route<ref name="VanBeusekomGlobal20">{{cite web |url=https://www.cidrap.umn.edu/news-perspective/2020/07/global-experts-ignoring-airborne-covid-spread-risky |title=Global experts: Ignoring airborne COVID spread risky |author=Van Beusekom, M. |work=Center for Infectious Disease Research and Policy |publisher=University of Minnesota |date=06 July 2020 |accessdate=07 July 2020}}</ref><ref name="DucharmeTheWHO20">{{cite web |url=https://time.com/5863220/airborne-coronavirus-transmission/ |title=The WHO Says Airborne Coronavirus Transmission Isn't a Big Risk. Scientists Are Pushing Back |author=Ducharme, J. |work=Time |date=07 July 2020 |accessdate=07 July 2020}}</ref><ref name="PennCOVID20">{{cite web |url=https://www.pennmedicine.org/updates/blogs/penn-physician-blog/2020/august/airborne-droplet-debate-article |title=COVID-19 Transmission: Droplet or Airborne? Penn Medicine Epidemiologists Issue Statement |author=Penn Medicine |work=Penn Physician Blog |date=02 August 2020 |accessdate=23 August 2020}}</ref><ref name="GreenhalghTen21">{{cite journal |title=Ten scientific reasons in support of airborne transmission of SARS-CoV-2 |journal=Lancet |author=Greenhalgh, T.; Jimenez, J.L.; Prather, K.A. et al. |volume=397 |issue=10285 |pages=1603–5 |year=2021 |doi=10.1016/S0140-6736(21)00869-2 |pmid=33865497 |pmc=PMC8049599}}</ref>, though transmission from contaminated surfaced or physical intimacy are also believed possible.<ref name="CDCScienceBrief21">{{cite web |url=https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/more/science-and-research/surface-transmission.html |title=Science Brief: SARS-CoV-2 and Surface (Fomite) Transmission for Indoor Community Environments |publisher=Centers for Disease Control and Prevention |date=05 April 2021 |accessdate=06 September 2021}}</ref><ref name="WinterVerifyYes21">{{cite web |url=https://www.wusa9.com/article/news/verify/yes-vaccinated-people-can-transmit-covid-through-kissing/536-00d88093-498c-4e58-9db6-331a69618248 |title=VERIFY: Yes, vaccinated people can transmit COVID-19 through kissing |author=Winter, E.; Datil, A. |work=WUSA9 - Verify |date=27 May 2021 |accessdate=06 September 2021}}</ref> Hospitalization rates are higher, perhaps up to 10 times higher than the flu, and hospital stays are longer with COVID-19. People are dying more often from COVID-19 too, up to 10 times more often than people stricken with the flu.<ref name="HuangHow20">{{cite web |url=https://www.npr.org/sections/goatsandsoda/2020/03/20/815408287/how-the-novel-coronavirus-and-the-flu-are-alike-and-different |title=How The Novel Coronavirus And The Flu Are Alike ... And Different |author=Huang, P. |work=NPR: Goats and Soda |date=20 March 2020 |accessdate=01 April 2020}}</ref><ref name="ResnickWhy20">{{cite web |url=https://www.vox.com/science-and-health/2020/3/18/21184992/coronavirus-covid-19-flu-comparison-chart |title=Why Covid-19 is worse than the flu, in one chart |author=Resnick, B.; Animashaun, C. |work=Vox |date=18 March 2020 |accessdate=01 April 2020}}</ref><ref name="KumarCOVID20">{{cite web |url=https://abcnews.go.com/Health/covid-19-compared-flu-experts-wrong/story?id=69779116 |title=COVID-19 has been compared to the flu. Experts say that's wrong |author=Kumar, V. |work=ABC News |date=27 March 2020 |accessdate=01 April 2020}}</ref> And while flu vaccines are largely the norm around the world, and COVID-19 vaccines are gradually becoming more available, those who willing choose to not get the vaccine have a massively higher chance of dying from COVID-19 (as of August 2021, more than 99 percent of all deaths from COVID-19 are found with the unvaccinated<ref name="MostMyths21">{{cite web |url=https://www.bu.edu/articles/2021/myths-vs-facts-covid-19-vaccine/ |title=Myths vs. Facts: Making Sense of COVID-19 Vaccine Misinformation |author=Most, D. |work=The Brink |date=13 August 2021 |accessdate=06 September 2021}}</ref>, compared to some 80% of children who die from the flu while unvaccinated<ref name="USAFacts61000_21">{{cite web |url=https://usafacts.org/articles/how-many-people-die-flu/ |title=61,000 people died in the worst flu season of the past decade. COVID-19 has killed eight times that many |publisher=USAFacts |date=29 July 2021 |accessdate=06 September 2021}}</ref>). | |||

Other aspects of the disease that make it difficult to manage include: | |||

* ''Median incubation period'': According to research published in ''Annals of Internal Medicine'', the median (i.e., the central tendency, which is less skewed than average<ref name="NRCSMedian">{{cite web |url=https://www.wcc.nrcs.usda.gov/normals/median_average.htm |title=Median vs. Average to Describe Normal |author=National Water and Climate Center |publisher=U.S. Department of Agriculture |accessdate=01 April 2020}}</ref>) incubation period is 5.1 days (Note that as new variants arrive, incubation times my change; the delta variant is thought to have an incubation period of four days, for example.<ref name="KochvarDelta21">{{cite web |url=https://www.nch.org/news/delta-variant-questions-answered/ |title=Delta variant questions answered |author=Kochvar, G.; Shah, A. |publisher=Northwest Community Healthcare |date=16 August 2021 |accessdate=06 September 2021}}</ref>), with 97.5% of symptomatic carriers showing symptoms within 11.5 days. The authors found this to be compatible with U.S. government recommendations of monitored 14-day self-quarantines if individuals were at risk of exposure.<ref name="LauerTheInc20">{{cite journal |title=The Incubation Period of Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) From Publicly Reported Confirmed Cases: Estimation and Application |journal=Annals of Internal Medicine |author=Lauer, S.A.; Grantz, K.H.; Bi, Q. et al. |year=2020 |doi=10.7326/M20-0504 |pmid=32150748 |pmc=PMC7081172}}</ref> However, many people continue to not take mask-wearing—and vaccination—seriously, and thus unmasked presymptomatic (and asymptomatic) carriers are thus largely more prone to spreading the virus.<ref name="MandavilliInfected20">{{cite web |url=https://www.nytimes.com/2020/03/31/health/coronavirus-asymptomatic-transmission.html |title=Infected but Feeling Fine: The Unwitting Coronavirus Spreaders |author=Mandavilli, A. |work=The New York Times |date=31 March 2020 |accessdate=01 April 2020}}</ref><ref name="MockAsymptom20">{{cite web |url=https://www.discovermagazine.com/health/asymptomatic-carriers-are-fueling-the-covid-19-pandemic-heres-why-you-dont |title=Asymptomatic Carriers Are Fueling the COVID-19 Pandemic. Here’s Why You Don’t Have to Feel Sick to Spread the Disease |author=Mock, J. |work=Discover |date=26 March 2020 |accessdate=01 April 2020}}</ref> This has become even more precarious with the highly contagious delta variant, which can be spread even by the vaccinated, highlighting that "measures such as masks and hand hygiene which can reduce transmission are important for everyone, regardless of vaccination status."<ref name="SubbaramanHowDo21">{{cite journal |title=How do vaccinated people spread Delta? What the science says |journal=Nature |author=Subbaraman, N. |volume=596 |pages=327–28 |year=2021 |doi=10.1038/d41586-021-02187-1 |pmid=34385613}}</ref> | |||

* ''Presymptomatic and asymptomatic virus shedding'': As mentioned in the previous point, carriers can be contagious during the presymptomatic phase of the disease, even while remaining symptom-free.<ref name="MandavilliInfected20" /><ref name="MockAsymptom20" /><ref name="YuenSARS20">{{cite journal |title=SARS-CoV-2 and COVID-19: The most important research questions |journal=Cell & Bioscience |author=Yuen, K.-S.; Fung, S.-Y.; Chan, C.-P.; Jin, D.-Y. |volume=10 |at=40 |year=2020 |doi=10.1186/s13578-020-00404-4 |pmid=32190290 |pmc=PMC7074995}}</ref><ref name="DiamondAsympt20">{{cite web |url=https://www.infectioncontroltoday.com/view/asymptomatic-carriers-covid-19-make-it-tough-target |title=Asymptomatic Carriers of COVID-19 Make It Tough to Target |author=Diamond, F. |work=Infection Control Today |date=17 March 2020 |accessdate=06 September 2021}}</ref> (The latest comprehensive research, from August 2021, appears to indicate that 35.1 percent of infected people may go without any recognizable symptoms after infection occurs.<ref name="SahAsymptom21>{{cite journal |title=Asymptomatic SARS-CoV-2 infection: A systematic review and meta-analysis |journal=PNAS |author=Sah, P.; Fitzpatrick, M.C.; Zimmer, C.F. et al. |volume=118 |issue=34 |at=e2109229118 |year=2021 |doi=10.1073/pnas.2109229118 |pmid=34376550}}</ref>) This contagion is a result of what's called [[viral shedding]], when the virus moves from cell to cell following successful reproduction. When the virus is in this state, it can be actively found in a carrier's body fluids, excrement, and other sources. Depending on the virus, the virus can then be introduced to another person via those sources. In the case of COVID-19, the core route of transmission appears to be through the air via aerosolized and other forms of water droplets, though saliva and other bodily constituents pose a transmission hazard due to shedding (see previous bulletpoint). Early in the pandemic, uncertainty about transmission routes of viral shedding, along with mixed messages early on about masks and their effectiveness for COVID-19<ref name="GreenfieldboyceWHO20">{{cite web |url=https://www.npr.org/2020/03/28/823292062/who-reviews-available-evidence-on-coronavirus-transmission-through-air |title=WHO Reviews 'Current' Evidence On Coronavirus Transmission Through Air |author=Greenfieldboyce, N. |work=NPR |date=28 March 2020 |accessdate=01 April 2020}}</ref><ref name="CSTEditorialIgnore31">{{cite web |url=https://chicago.suntimes.com/2020/3/31/21200144/coronavirus-covid-19-masks-wear-cdc-pritzker-trump-public-health-virus-face-cough-sneeze |title=Ignore the mixed messages and wear that mask |author=Chicago Sun Times Editorial Board |work=Chicago Sun Times |date=31 March 2020 |accessdate=01 April 2020}}</ref><ref name="MulhollandToMask20">{{cite web |url=http://www.rfi.fr/en/international/20200329-to-mask-or-not-to-mask-mixed-messages-in-a-time-of-coronavirus-crisis-france-covid-19-spread-droplets |title=To mask or not to mask: mixed messages in a time of crisis |author=Mulholland, J. |work=RFI |date=29 March 2020 |accessdate=01 April 2020}}</ref>, caused problems. Today we know that masks and social distancing—when appropriate—are an even stronger necessity to limit community transmission of the disease from presymptomatic and asymptomatic individuals, even for those who are vaccinated.<ref name="SubbaramanHowDo21" /> | |||

* ''Understanding of high viral loads and infectious doses'': Respiratory diseases such as influenza, SARS, and MERS see a correlation between the infectious dose amount and the severity of disease symptoms, meaning the higher the infectious dose, the worse the symptoms.<ref name="GeddesDoesA20">{{cite web |url=https://www.newscientist.com/article/2238819-does-a-high-viral-load-or-infectious-dose-make-covid-19-worse/ |title=Does a high viral load or infectious dose make covid-19 worse? |author=Geddes, L. |work=New Scientist |date=27 March 2020 |accessdate=01 April 2020}}</ref> Similarly, viral load—a quantification of viral genomic fragments—also tends to correlate with clinical symptoms.<ref name="HijanoClinical19">{{cite journal |title=Clinical correlation of influenza and respiratory syncytial virus load measured by digital PCR |journal=PLoS One |author=Hijano, D.R.; Brazelton de Cardenas, J.; Maron, G. et al. |volume=14 |issue=9 |at=e0220908 |year=2019 |doi=10.1371/journal.pone.0220908 |pmid=31479459 |pmc=PMC6720028}}</ref> However, even with the breakthroughs in COVID research since the start of the pandemic, we are still in the investigative stages of definitively determining if that similarly holds true to COVID-19.<ref name="GeddesDoesA20" /><ref name="LiuViral20">{{cite journal |title=Viral dynamics in mild and severe cases of COVID-19 |journal=The Lancet Infectious Diseases |author=Liu, Y.; Yan, L.-M.; Wan, L. et al. |year=2020 |doi=10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30232-2 |pmid=32199493}}</ref><ref name="JoyntUnder20">{{cite journal |title=Understanding COVID-19: what does viral RNA load really mean? |journal=The Lancet Infectious Diseases |author=Joynt, G.M.; Wu, W.K.K. |year=2020 |doi=10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30237-1}}</ref> Research early on indicated, for example, there is little difference between the viral load of those with mild or no COVID-19 symptoms and those with more severe symptoms.<ref name="GeddesDoesA20" /> However, Pujadas ''et al.'' suggested a link between high viral load and overall mortality rate.<ref name="PujadasSARS20">{{cite journal |title=SARS-CoV-2 viral load predicts COVID-19 mortality |journal=The Lancet Respiratory Medicine |author=Pujadas, E.; Chaudhry, F.; McBride, R. et al. |year=2020 |doi=10.1016/S2213-2600(20)30354-4}}</ref> Research later in 2020 has suggested more of a positive correlation between severity of symptoms and viral load<ref name="FajnzylberSARS20">{{cite journal |title=SARS-CoV-2 viral load is associated with increased disease severity and mortality |journal=Nature Communications |author=Fajnzylber, J.; Regan, J.; Coxen, K. et al. |volume=11 |at=5493 |year=2020 |doi=10.1038/s41467-020-19057-5 |pmid=33127906 |pmc=PMC7603483}}</ref><ref name="AlAliSARS20">{{cite journal |title=SARS-Cov-2 Viral Load as an Indicator for COVID-19 Patients’ Hospital Stay |journal=medRxiv |year=2020 |doi=10.1101/2020.11.04.20226365}}</ref>, as has a July 2021 study published in ''Science''.<ref name="JonesEstim21">{{cite journal |title=Estimating infectiousness throughout SARS-CoV-2 infection course |journal=Science |author=Jones, T.C.; Biele, G.; Mühlemann, B. et al. |volume=373 |issue=6551 |at=abi5273 |year=2021 |doi=10.1126/science.abi5273 |pmid=34035154}}</ref> However, more research must be performed to better understand how the viral load infectious dose plays a role in transmission. Given the continued unknowns in this realm, wearing masks and getting vaccinate help minimize exposure and remain the best defense against the worst outcomes of the disease.<ref name="GeddesDoesA20" /> | |||

* ''Cardiovascular issues'': Coronaviruses and their accompanying respiratory infections are known to complicate issues of the cardiovascular system, which in turn may "increase the incidence and severity" of infectious diseases such as SARS and COVID-19.<ref name="MadjidPotent20">{{cite journal |title=Potential Effects of Coronaviruses on the Cardiovascular System |journal=JAMA Cardiology |author=Madjid, M.; Safavi-Naeini, P.; Solomon, S.D. |year=2020 |doi=10.1001/jamacardio.2020.1286 |pmid=32219363}}</ref><ref name="XiongCorona20">{{cite journal |title=Coronaviruses and the cardiovascular system: acute and long-term implications |journal=European Heart Journal |author=Xiong, T.-Y.; Redwood, S.; Prendergast, B.; Chen, M. |at=ehaa231 |year=2020 |doi=10.1093/eurheartj/ehaa231 |pmid=32186331}}</ref><ref name="DrigginCardio20">{{cite journal |title=Cardiovascular Considerations for Patients, Health Care Workers, and Health Systems During the Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) Pandemic |journal=Journal of the American College of Cardiology |author=Driggin, E.; Madhavan, M.V.; Bikdeli, B. et al. |year=2020 |doi=10.1016/j.jacc.2020.03.031 |pmid=32201335}}</ref> While the exact cardiac effect COVID-19 has on patients is still unknown, suspicion is those with "hypertension, diabetes, and diagnosed cardiovascular disease" may be more prone to having cardiovascular complications from the disease.<ref name="OttoCardiac20">{{cite web |url=https://www.the-hospitalist.org/hospitalist/article/219645/coronavirus-updates/cardiac-symptoms-can-be-first-sign-covid-19 |title=Cardiac symptoms can be first sign of COVID-19 |author=Otto, M.A. |work=The Hospitalist |date=26 March 2020 |accessdate=01 April 2020}}</ref><ref name="ClerkinCorona20">{{cite journal |title=Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) and Cardiovascular Disease |journal=Circulation |author=Clerkin, K.J.; Fried, J.A.; Raikhelkar, J. et al. |year=2020 |doi=10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.120.046941 |pmid=32200663}}</ref> Current thinking is SARS-CoV-2 either attacks heart tissues, causing myocardial dysfunction, or inevitably causes heart failure through a "cytokine storm,"<ref name="MadjidPotent20" /><ref name="XiongCorona20" /><ref name="OttoCardiac20" /><ref name="ClerkinCorona20" /><ref name="MehtaCOVID20">{{cite journal |title=COVID-19: Consider cytokine storm syndromes and immunosuppression |journal=The Lancet |author=Mehta, P.; McAuley, D.F.; Brown, M. et al. |volume=395 |issue=10229 |pages=P1033–34 |year=2020 |doi=10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30628-0 |pmid=32192578}}</ref><ref name="MandavilliTheCoronaCyto20">{{cite web |url=https://www.nytimes.com/2020/04/01/health/coronavirus-cytokine-storm-immune-system.html |title=The Coronavirus Patients Betrayed by Their Own Immune Systems |author=Mandavilli, A. |work=The New York Times |date=01 April 2020 |accessdate=01 April 2020}}</ref><ref name="WeidmannLab20">{{cite journal |title=Laboratory Biomarkers in the Management of Patients With COVID-19 |journal=American Journal of Clinical Pathology |author=Weidmann, M.D.; Otori, J.; Rai, A.J. |at=aqaa205 |year=2020 |doi=10.1093/ajcp/aqaa205 |pmid=33107558}}</ref>, an overproduction of signaling molecules that promote inflammation by white blood cells (leukocytes).<ref name="TisoncikInto12">{{cite journal |title=Into the eye of the cytokine storm |journal=Microbiology and Molecular Biology Reviews |author=Tisoncik, J.R.; Korth, M.J.; Simmons, C.P. et al. |volume=76 |issue=1 |pages=16–32 |year=2012 |doi=10.1128/MMBR.05015-11 |pmid=22390970 |pmc=PMC3294426}}</ref><ref name="YangTheSig21">{{cite journal |title=The signal pathways and treatment of cytokine storm in COVID-19 |journal=Signal Transduction and Targeted Therapy |author=Yang, L.; Xie, X.; Tu, Z. et al. |volume=6 |at=255 |year=2021 |doi=10.1038/s41392-021-00679-0 |pmid=34234112 |pmc=PMC8261820}}</ref> What's scary is that like the 1918 Spanish flu, SARS, and other epidemics, some otherwise healthy patients' immune responses are entirely overreactive, leading to acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) or heart failure.<ref name="WeidmannLab20" /><ref name="MandavilliTheCoronaCyto20" /><ref name="BasilioANew20">{{cite web |url=https://www.mdlinx.com/article/a-new-potential-risk-of-covid-19-sudden-cardiac-death/3z05mHtQN0PL1EdhlWltmH |title=A new potential risk of COVID-19: Sudden cardiac death |author=Basilio, P. |work=MDLinx |date=26 March 2020 |accessdate=06 September 2021}}</ref> Additionally, as the disease has progressed, medical professionals have noted two additional cardiovascular issues. First, an atypical amount of blood clotting has shown up in some infected patients, which may be related to overreactive immune systems, autoantibodies, and underlying health conditions.<ref name="RettnerMyster20">{{cite web |url=https://www.livescience.com/coronavirus-blood-clots.html |title=Mysterious blood clots in COVID-19 patients have doctors alarmed |author=Rettner, R. |work=LiveScience |date=23 April 2020 |accessdate=28 April 2020}}</ref><ref name="HamptonAuto21">{{cite journal |title=Autoantibodies May Drive COVID-19 Blood Clots |journal=JAMA |author=Hampton, T. |volume=325 |issue=5 |page=425 |year=2021 |doi=10.1001/jama.2020.25699 |pmid=33528515}}</ref> Second, what is being called pediatric multisystem inflammatory syndrome (PMIS) or multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children (MIS-C) has shown up in children after the infection has passed, characterized by inflamed blood vessels and toxic shock syndrome.<ref name="MoyerWhatWe20">{{cite web |url=https://www.nytimes.com/2020/05/19/parenting/pmis-coronavirus-children.html |title=What We Know About the Covid-Related Syndrome Affecting Children |work=The New York Times |author=Moyer, M.W. |date=19 May 2020 |accessdate=19 May 2020}}</ref><ref name="FischerWhatTo20">{{cite web |url=https://www.healthline.com/health-news/what-to-know-pmis-syndrome-linked-to-covid-19-affects-children |title=What to Know About PMIS, the COVID-19-Linked Syndrome Affecting Children |work=Healthline |author=Fischer, K. |date=18 May 2020 |accessdate=19 May 2020}}</ref><ref name="MacMillanResearch21">{{cite web |url=https://www.yalemedicine.org/news/multisystem-inflammatory-syndrome-in-children-misc-covid-kids |title=Researchers Continue to Find Clues About MIS-C |author=MacMillan, C. |work=Yale Medicine |publisher=Yale University |date=14 July 2021 |accessdate=06 September 2021}}</ref> While research is ongoing to determine whether these seemingly hyperactive cardiovascular responses are directly linked to the virus<ref name="MannePlatelet20">{{cite journal |title=Platelet Gene Expression and Function in COVID-19 Patients |journal=Blood |author=Manne, B.K.; Denorme, F.; Middleton, E.A. et al. |at=blood.2020007214 |year=2020 |doi=10.1182/blood.2020007214}}</ref> or if virus-independent immunopathology is responsible<ref name="DorwardTissue20">{{cite journal |title=Tissue-specific tolerance in fatal Covid-19 |journal=medRxiv |author=Dorward, D.A.; Russell, C.D.; Um, I.H. et al. |year=2020 |doi=10.1101/2020.07.02.20145003}}</ref>, these uncertainties only emphasize the level of difficulty of properly treating COVID-19. | |||

* | * ''Other systemic and bodily issues'': As the pandemic has progressed, researchers have discovered SARS-CoV-2 appears to negatively impact other organs and systems in the human body, including the renal system, digestive system, endocrine system, neurological system, and even the reproductive system.<ref name="WeidmannLab20" /><ref name="CDCSymptoms20">{{cite web |url=https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/symptoms-testing/symptoms.html |title=Symptoms of Coronavirus |author=Centers for Disease Control and Preventions |publisher=Centers for Disease Control and Preventions |date=22 February 2021 |accessdate=06 September 2021}}</ref><ref name="MayoCOVID20">{{cite web |url=https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/coronavirus/in-depth/coronavirus-long-term-effects/art-20490351 |title=COVID-19 (coronavirus): Long-term effects |author=Mayo Clinic Staff |publisher=Mayo Clinic |date=07 October 2020 |accessdate=12 November 2020}}</ref><ref name="BudsonTheHidden20">{{cite web |url=https://www.health.harvard.edu/blog/the-hidden-long-term-cognitive-effects-of-covid-2020100821133 |title=The hidden long-term cognitive effects of COVID-19 |author=Budson, A.E. |work=Harvard Health Blog |date=08 October 2020 |accessdate=12 November 2020}}</ref><ref name="MaCOVID20">{{cite journal |title=COVID-19 and the Digestive System |journal=American Journal of Gastroenterology |author=Ma, C.; Cong, Y.; Zhang, H. |volume=115 |issue=7 |pages=1003–6 |year=2020 |doi=10.14309/ajg.0000000000000691 |pmid=32618648 |pmc=PMC7273952}}</ref> Another bodily issue that appears to remain for a subset of post-recovery COVID-19 patients is fatigue. The University of Minnesota's Center for Infectious Disease Research and Policy reports on an observational study published in ''PLOS One''' that showed more than half of people who recovered from their COVID-19 infection still dealt with the lingering effects of fatigue at a median of 10 weeks after recovery. The study reports no link between the persistent fatigue and severity of symptoms, need for hospitalization, concentration of laboratory biomarkers, and age.<ref name="VanBeusekomHalf20">{{cite web |url=https://www.cidrap.umn.edu/news-perspective/2020/11/half-recovered-covid-19-patients-report-lingering-fatigue |title=Half of recovered COVID-19 patients report lingering fatigue |author=Van Beusekom, M. |work=CUDRAP News & Perspective |publisher=University of Minnesota |date=11 November 2020 |accessdate=18 November 2020}}</ref> These systemic and body issues have added further complication to an already complicated disease, making extended treatment planning difficult. The long-term affects of these and other organ system injuries remains to be fully understood. | ||

* ''Mental health concerns'': The mental health toll of the pandemic is becoming increasingly apparent as it wears on. A June 2020 CDC survey of 5,412 U.S. adults (regardless of infection status) "found that 40.9% of respondents reported 'at least one adverse mental or behavioral health condition,' including depression, anxiety, posttraumatic stress, and substance abuse, with rates that were three to four times the rates one year earlier." More than 10 percent of respondents also indicated they had seriously considered suicide in a time period thirty days prior to responding.<ref name="SimonMental20">{{cite journal |title=Mental Health Disorders Related to COVID-19–Related Deaths |journal=JAMA |author=Simon, N.M.; Saxe, G.N.; Marmar, C.R. |volume=324 |issue=15 |pages=1493–94 |year=2020 |doi=10.1001/jama.2020.19632 |pmid=33044510}}</ref> From an inability to grieve communally with loved ones, to income loss, increased anxiety, and long periods of social isolation, these increasing numbers are not surprising, particularly in light of research on previous pandemics.<ref name="SimonMental20" /><ref name="SavageCorona20">{{cite web |url=https://www.bbc.com/worklife/article/20201021-coronavirus-the-possible-long-term-mental-health-impacts |title=Coronavirus: The possible long-term mental health impacts |author=Savage, M. |work=BBC Worklife |date=28 October 2020 |accessdate=18 November 2020}}</ref> Without proper treatment, these conditions may worsen into prolonged grief disorder, only exasperating a growing mental health crisis.<ref name="SimonMental20" /> Further, at least one study suggests that those who contract COVID-19 may be at a greater risk of developing some sort of mental illness within 90 days, including anxiety, depression, and insomnia. This effect may be worse for those who already have a history of mental health illness.<ref name="KellandStudy20">{{cite web |url=https://www.insurancejournal.com/news/international/2020/11/09/590113.htm |title=Study Shows COVID-19 Patients at Greater Risk of Mental Health Problems |author=Kelland, K. |work=Insurance Journal |date=09 November 2020 |accessdate=18 November 2020}}</ref> Mitigating the effects of these mental health concerns will require further study, greater funding, expanded screening, and improved focus on community methods of dealing with tragedy and loss.<ref name="SimonMental20" /> | |||

==References== | ==References== | ||

{{Reflist|colwidth=30em}} | {{Reflist|colwidth=30em}} | ||

Revision as of 16:38, 3 February 2022

COVID-19 has presented numerous societal challenges, from supply line interruptions and economic sagging to overwhelmed healthcare systems and civil disorder. However, these are largely the social, economic, and political ripple effects of a disease that has brought with it a set of inherent attributes that make it more difficult to manage in human populations than say the flu.

However, COVID-19 is not the flu, and it is indeed worse in its effects than the flu, contrary to many people's perceptions. Yes, COVID-19 and the flu have some symptom overlap. Yes, COVID-19 and the flu have some transmission type overlap. But from there it diverges. COVID-19 and SARS-CoV-2 is different in that it is more prone to be transmitted to others during the presymptomatic phase. And the body of evidence has grown since early on in the pandemic[1] that SARS-CoV-2 is transmittable predominately via an airborne route[2][3][4][5], though transmission from contaminated surfaced or physical intimacy are also believed possible.[6][7] Hospitalization rates are higher, perhaps up to 10 times higher than the flu, and hospital stays are longer with COVID-19. People are dying more often from COVID-19 too, up to 10 times more often than people stricken with the flu.[8][9][10] And while flu vaccines are largely the norm around the world, and COVID-19 vaccines are gradually becoming more available, those who willing choose to not get the vaccine have a massively higher chance of dying from COVID-19 (as of August 2021, more than 99 percent of all deaths from COVID-19 are found with the unvaccinated[11], compared to some 80% of children who die from the flu while unvaccinated[12]).

Other aspects of the disease that make it difficult to manage include:

- Median incubation period: According to research published in Annals of Internal Medicine, the median (i.e., the central tendency, which is less skewed than average[13]) incubation period is 5.1 days (Note that as new variants arrive, incubation times my change; the delta variant is thought to have an incubation period of four days, for example.[14]), with 97.5% of symptomatic carriers showing symptoms within 11.5 days. The authors found this to be compatible with U.S. government recommendations of monitored 14-day self-quarantines if individuals were at risk of exposure.[15] However, many people continue to not take mask-wearing—and vaccination—seriously, and thus unmasked presymptomatic (and asymptomatic) carriers are thus largely more prone to spreading the virus.[16][17] This has become even more precarious with the highly contagious delta variant, which can be spread even by the vaccinated, highlighting that "measures such as masks and hand hygiene which can reduce transmission are important for everyone, regardless of vaccination status."[18]

- Presymptomatic and asymptomatic virus shedding: As mentioned in the previous point, carriers can be contagious during the presymptomatic phase of the disease, even while remaining symptom-free.[16][17][19][20] (The latest comprehensive research, from August 2021, appears to indicate that 35.1 percent of infected people may go without any recognizable symptoms after infection occurs.[21]) This contagion is a result of what's called viral shedding, when the virus moves from cell to cell following successful reproduction. When the virus is in this state, it can be actively found in a carrier's body fluids, excrement, and other sources. Depending on the virus, the virus can then be introduced to another person via those sources. In the case of COVID-19, the core route of transmission appears to be through the air via aerosolized and other forms of water droplets, though saliva and other bodily constituents pose a transmission hazard due to shedding (see previous bulletpoint). Early in the pandemic, uncertainty about transmission routes of viral shedding, along with mixed messages early on about masks and their effectiveness for COVID-19[22][23][24], caused problems. Today we know that masks and social distancing—when appropriate—are an even stronger necessity to limit community transmission of the disease from presymptomatic and asymptomatic individuals, even for those who are vaccinated.[18]

- Understanding of high viral loads and infectious doses: Respiratory diseases such as influenza, SARS, and MERS see a correlation between the infectious dose amount and the severity of disease symptoms, meaning the higher the infectious dose, the worse the symptoms.[25] Similarly, viral load—a quantification of viral genomic fragments—also tends to correlate with clinical symptoms.[26] However, even with the breakthroughs in COVID research since the start of the pandemic, we are still in the investigative stages of definitively determining if that similarly holds true to COVID-19.[25][27][28] Research early on indicated, for example, there is little difference between the viral load of those with mild or no COVID-19 symptoms and those with more severe symptoms.[25] However, Pujadas et al. suggested a link between high viral load and overall mortality rate.[29] Research later in 2020 has suggested more of a positive correlation between severity of symptoms and viral load[30][31], as has a July 2021 study published in Science.[32] However, more research must be performed to better understand how the viral load infectious dose plays a role in transmission. Given the continued unknowns in this realm, wearing masks and getting vaccinate help minimize exposure and remain the best defense against the worst outcomes of the disease.[25]

- Cardiovascular issues: Coronaviruses and their accompanying respiratory infections are known to complicate issues of the cardiovascular system, which in turn may "increase the incidence and severity" of infectious diseases such as SARS and COVID-19.[33][34][35] While the exact cardiac effect COVID-19 has on patients is still unknown, suspicion is those with "hypertension, diabetes, and diagnosed cardiovascular disease" may be more prone to having cardiovascular complications from the disease.[36][37] Current thinking is SARS-CoV-2 either attacks heart tissues, causing myocardial dysfunction, or inevitably causes heart failure through a "cytokine storm,"[33][34][36][37][38][39][40], an overproduction of signaling molecules that promote inflammation by white blood cells (leukocytes).[41][42] What's scary is that like the 1918 Spanish flu, SARS, and other epidemics, some otherwise healthy patients' immune responses are entirely overreactive, leading to acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) or heart failure.[40][39][43] Additionally, as the disease has progressed, medical professionals have noted two additional cardiovascular issues. First, an atypical amount of blood clotting has shown up in some infected patients, which may be related to overreactive immune systems, autoantibodies, and underlying health conditions.[44][45] Second, what is being called pediatric multisystem inflammatory syndrome (PMIS) or multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children (MIS-C) has shown up in children after the infection has passed, characterized by inflamed blood vessels and toxic shock syndrome.[46][47][48] While research is ongoing to determine whether these seemingly hyperactive cardiovascular responses are directly linked to the virus[49] or if virus-independent immunopathology is responsible[50], these uncertainties only emphasize the level of difficulty of properly treating COVID-19.

- Other systemic and bodily issues: As the pandemic has progressed, researchers have discovered SARS-CoV-2 appears to negatively impact other organs and systems in the human body, including the renal system, digestive system, endocrine system, neurological system, and even the reproductive system.[40][51][52][53][54] Another bodily issue that appears to remain for a subset of post-recovery COVID-19 patients is fatigue. The University of Minnesota's Center for Infectious Disease Research and Policy reports on an observational study published in PLOS One' that showed more than half of people who recovered from their COVID-19 infection still dealt with the lingering effects of fatigue at a median of 10 weeks after recovery. The study reports no link between the persistent fatigue and severity of symptoms, need for hospitalization, concentration of laboratory biomarkers, and age.[55] These systemic and body issues have added further complication to an already complicated disease, making extended treatment planning difficult. The long-term affects of these and other organ system injuries remains to be fully understood.

- Mental health concerns: The mental health toll of the pandemic is becoming increasingly apparent as it wears on. A June 2020 CDC survey of 5,412 U.S. adults (regardless of infection status) "found that 40.9% of respondents reported 'at least one adverse mental or behavioral health condition,' including depression, anxiety, posttraumatic stress, and substance abuse, with rates that were three to four times the rates one year earlier." More than 10 percent of respondents also indicated they had seriously considered suicide in a time period thirty days prior to responding.[56] From an inability to grieve communally with loved ones, to income loss, increased anxiety, and long periods of social isolation, these increasing numbers are not surprising, particularly in light of research on previous pandemics.[56][57] Without proper treatment, these conditions may worsen into prolonged grief disorder, only exasperating a growing mental health crisis.[56] Further, at least one study suggests that those who contract COVID-19 may be at a greater risk of developing some sort of mental illness within 90 days, including anxiety, depression, and insomnia. This effect may be worse for those who already have a history of mental health illness.[58] Mitigating the effects of these mental health concerns will require further study, greater funding, expanded screening, and improved focus on community methods of dealing with tragedy and loss.[56]

References

- ↑ Achenach, J.; Johnson, C.Y. (29 April 2020). "Studies leave question of ‘airborne’ coronavirus transmission unanswered". The Washington Post. https://www.washingtonpost.com/health/2020/04/29/studies-leave-question-airborne-coronavirus-transmission-unanswered/. Retrieved 01 May 2020.

- ↑ Van Beusekom, M. (6 July 2020). "Global experts: Ignoring airborne COVID spread risky". Center for Infectious Disease Research and Policy. University of Minnesota. https://www.cidrap.umn.edu/news-perspective/2020/07/global-experts-ignoring-airborne-covid-spread-risky. Retrieved 07 July 2020.

- ↑ Ducharme, J. (7 July 2020). "The WHO Says Airborne Coronavirus Transmission Isn't a Big Risk. Scientists Are Pushing Back". Time. https://time.com/5863220/airborne-coronavirus-transmission/. Retrieved 07 July 2020.

- ↑ Penn Medicine (2 August 2020). "COVID-19 Transmission: Droplet or Airborne? Penn Medicine Epidemiologists Issue Statement". Penn Physician Blog. https://www.pennmedicine.org/updates/blogs/penn-physician-blog/2020/august/airborne-droplet-debate-article. Retrieved 23 August 2020.

- ↑ Greenhalgh, T.; Jimenez, J.L.; Prather, K.A. et al. (2021). "Ten scientific reasons in support of airborne transmission of SARS-CoV-2". Lancet 397 (10285): 1603–5. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(21)00869-2. PMC PMC8049599. PMID 33865497. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC8049599.

- ↑ "Science Brief: SARS-CoV-2 and Surface (Fomite) Transmission for Indoor Community Environments". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 5 April 2021. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/more/science-and-research/surface-transmission.html. Retrieved 06 September 2021.

- ↑ Winter, E.; Datil, A. (27 May 2021). "VERIFY: Yes, vaccinated people can transmit COVID-19 through kissing". WUSA9 - Verify. https://www.wusa9.com/article/news/verify/yes-vaccinated-people-can-transmit-covid-through-kissing/536-00d88093-498c-4e58-9db6-331a69618248. Retrieved 06 September 2021.

- ↑ Huang, P. (20 March 2020). "How The Novel Coronavirus And The Flu Are Alike ... And Different". NPR: Goats and Soda. https://www.npr.org/sections/goatsandsoda/2020/03/20/815408287/how-the-novel-coronavirus-and-the-flu-are-alike-and-different. Retrieved 01 April 2020.

- ↑ Resnick, B.; Animashaun, C. (18 March 2020). "Why Covid-19 is worse than the flu, in one chart". Vox. https://www.vox.com/science-and-health/2020/3/18/21184992/coronavirus-covid-19-flu-comparison-chart. Retrieved 01 April 2020.

- ↑ Kumar, V. (27 March 2020). "COVID-19 has been compared to the flu. Experts say that's wrong". ABC News. https://abcnews.go.com/Health/covid-19-compared-flu-experts-wrong/story?id=69779116. Retrieved 01 April 2020.

- ↑ Most, D. (13 August 2021). "Myths vs. Facts: Making Sense of COVID-19 Vaccine Misinformation". The Brink. https://www.bu.edu/articles/2021/myths-vs-facts-covid-19-vaccine/. Retrieved 06 September 2021.

- ↑ "61,000 people died in the worst flu season of the past decade. COVID-19 has killed eight times that many". USAFacts. 29 July 2021. https://usafacts.org/articles/how-many-people-die-flu/. Retrieved 06 September 2021.

- ↑ National Water and Climate Center. "Median vs. Average to Describe Normal". U.S. Department of Agriculture. https://www.wcc.nrcs.usda.gov/normals/median_average.htm. Retrieved 01 April 2020.

- ↑ Kochvar, G.; Shah, A. (16 August 2021). "Delta variant questions answered". Northwest Community Healthcare. https://www.nch.org/news/delta-variant-questions-answered/. Retrieved 06 September 2021.

- ↑ Lauer, S.A.; Grantz, K.H.; Bi, Q. et al. (2020). "The Incubation Period of Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) From Publicly Reported Confirmed Cases: Estimation and Application". Annals of Internal Medicine. doi:10.7326/M20-0504. PMC PMC7081172. PMID 32150748. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7081172.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 Mandavilli, A. (31 March 2020). "Infected but Feeling Fine: The Unwitting Coronavirus Spreaders". The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/03/31/health/coronavirus-asymptomatic-transmission.html. Retrieved 01 April 2020.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 Mock, J. (26 March 2020). "Asymptomatic Carriers Are Fueling the COVID-19 Pandemic. Here’s Why You Don’t Have to Feel Sick to Spread the Disease". Discover. https://www.discovermagazine.com/health/asymptomatic-carriers-are-fueling-the-covid-19-pandemic-heres-why-you-dont. Retrieved 01 April 2020.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 Subbaraman, N. (2021). "How do vaccinated people spread Delta? What the science says". Nature 596: 327–28. doi:10.1038/d41586-021-02187-1. PMID 34385613.

- ↑ Yuen, K.-S.; Fung, S.-Y.; Chan, C.-P.; Jin, D.-Y. (2020). "SARS-CoV-2 and COVID-19: The most important research questions". Cell & Bioscience 10: 40. doi:10.1186/s13578-020-00404-4. PMC PMC7074995. PMID 32190290. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7074995.

- ↑ Diamond, F. (17 March 2020). "Asymptomatic Carriers of COVID-19 Make It Tough to Target". Infection Control Today. https://www.infectioncontroltoday.com/view/asymptomatic-carriers-covid-19-make-it-tough-target. Retrieved 06 September 2021.

- ↑ Sah, P.; Fitzpatrick, M.C.; Zimmer, C.F. et al. (2021). "Asymptomatic SARS-CoV-2 infection: A systematic review and meta-analysis". PNAS 118 (34): e2109229118. doi:10.1073/pnas.2109229118. PMID 34376550.

- ↑ Greenfieldboyce, N. (28 March 2020). "WHO Reviews 'Current' Evidence On Coronavirus Transmission Through Air". NPR. https://www.npr.org/2020/03/28/823292062/who-reviews-available-evidence-on-coronavirus-transmission-through-air. Retrieved 01 April 2020.

- ↑ Chicago Sun Times Editorial Board (31 March 2020). "Ignore the mixed messages and wear that mask". Chicago Sun Times. https://chicago.suntimes.com/2020/3/31/21200144/coronavirus-covid-19-masks-wear-cdc-pritzker-trump-public-health-virus-face-cough-sneeze. Retrieved 01 April 2020.

- ↑ Mulholland, J. (29 March 2020). "To mask or not to mask: mixed messages in a time of crisis". RFI. http://www.rfi.fr/en/international/20200329-to-mask-or-not-to-mask-mixed-messages-in-a-time-of-coronavirus-crisis-france-covid-19-spread-droplets. Retrieved 01 April 2020.

- ↑ 25.0 25.1 25.2 25.3 Geddes, L. (27 March 2020). "Does a high viral load or infectious dose make covid-19 worse?". New Scientist. https://www.newscientist.com/article/2238819-does-a-high-viral-load-or-infectious-dose-make-covid-19-worse/. Retrieved 01 April 2020.

- ↑ Hijano, D.R.; Brazelton de Cardenas, J.; Maron, G. et al. (2019). "Clinical correlation of influenza and respiratory syncytial virus load measured by digital PCR". PLoS One 14 (9): e0220908. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0220908. PMC PMC6720028. PMID 31479459. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6720028.

- ↑ Liu, Y.; Yan, L.-M.; Wan, L. et al. (2020). "Viral dynamics in mild and severe cases of COVID-19". The Lancet Infectious Diseases. doi:10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30232-2. PMID 32199493.

- ↑ Joynt, G.M.; Wu, W.K.K. (2020). "Understanding COVID-19: what does viral RNA load really mean?". The Lancet Infectious Diseases. doi:10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30237-1.

- ↑ Pujadas, E.; Chaudhry, F.; McBride, R. et al. (2020). "SARS-CoV-2 viral load predicts COVID-19 mortality". The Lancet Respiratory Medicine. doi:10.1016/S2213-2600(20)30354-4.

- ↑ Fajnzylber, J.; Regan, J.; Coxen, K. et al. (2020). "SARS-CoV-2 viral load is associated with increased disease severity and mortality". Nature Communications 11: 5493. doi:10.1038/s41467-020-19057-5. PMC PMC7603483. PMID 33127906. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7603483.

- ↑ "SARS-Cov-2 Viral Load as an Indicator for COVID-19 Patients’ Hospital Stay". medRxiv. 2020. doi:10.1101/2020.11.04.20226365.

- ↑ Jones, T.C.; Biele, G.; Mühlemann, B. et al. (2021). "Estimating infectiousness throughout SARS-CoV-2 infection course". Science 373 (6551): abi5273. doi:10.1126/science.abi5273. PMID 34035154.

- ↑ 33.0 33.1 Madjid, M.; Safavi-Naeini, P.; Solomon, S.D. (2020). "Potential Effects of Coronaviruses on the Cardiovascular System". JAMA Cardiology. doi:10.1001/jamacardio.2020.1286. PMID 32219363.

- ↑ 34.0 34.1 Xiong, T.-Y.; Redwood, S.; Prendergast, B.; Chen, M. (2020). "Coronaviruses and the cardiovascular system: acute and long-term implications". European Heart Journal: ehaa231. doi:10.1093/eurheartj/ehaa231. PMID 32186331.

- ↑ Driggin, E.; Madhavan, M.V.; Bikdeli, B. et al. (2020). "Cardiovascular Considerations for Patients, Health Care Workers, and Health Systems During the Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) Pandemic". Journal of the American College of Cardiology. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2020.03.031. PMID 32201335.

- ↑ 36.0 36.1 Otto, M.A. (26 March 2020). "Cardiac symptoms can be first sign of COVID-19". The Hospitalist. https://www.the-hospitalist.org/hospitalist/article/219645/coronavirus-updates/cardiac-symptoms-can-be-first-sign-covid-19. Retrieved 01 April 2020.

- ↑ 37.0 37.1 Clerkin, K.J.; Fried, J.A.; Raikhelkar, J. et al. (2020). "Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) and Cardiovascular Disease". Circulation. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.120.046941. PMID 32200663.

- ↑ Mehta, P.; McAuley, D.F.; Brown, M. et al. (2020). "COVID-19: Consider cytokine storm syndromes and immunosuppression". The Lancet 395 (10229): P1033–34. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30628-0. PMID 32192578.

- ↑ 39.0 39.1 Mandavilli, A. (1 April 2020). "The Coronavirus Patients Betrayed by Their Own Immune Systems". The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/04/01/health/coronavirus-cytokine-storm-immune-system.html. Retrieved 01 April 2020.

- ↑ 40.0 40.1 40.2 Weidmann, M.D.; Otori, J.; Rai, A.J. (2020). "Laboratory Biomarkers in the Management of Patients With COVID-19". American Journal of Clinical Pathology: aqaa205. doi:10.1093/ajcp/aqaa205. PMID 33107558.

- ↑ Tisoncik, J.R.; Korth, M.J.; Simmons, C.P. et al. (2012). "Into the eye of the cytokine storm". Microbiology and Molecular Biology Reviews 76 (1): 16–32. doi:10.1128/MMBR.05015-11. PMC PMC3294426. PMID 22390970. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3294426.

- ↑ Yang, L.; Xie, X.; Tu, Z. et al. (2021). "The signal pathways and treatment of cytokine storm in COVID-19". Signal Transduction and Targeted Therapy 6: 255. doi:10.1038/s41392-021-00679-0. PMC PMC8261820. PMID 34234112. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC8261820.

- ↑ Basilio, P. (26 March 2020). "A new potential risk of COVID-19: Sudden cardiac death". MDLinx. https://www.mdlinx.com/article/a-new-potential-risk-of-covid-19-sudden-cardiac-death/3z05mHtQN0PL1EdhlWltmH. Retrieved 06 September 2021.

- ↑ Rettner, R. (23 April 2020). "Mysterious blood clots in COVID-19 patients have doctors alarmed". LiveScience. https://www.livescience.com/coronavirus-blood-clots.html. Retrieved 28 April 2020.

- ↑ Hampton, T. (2021). "Autoantibodies May Drive COVID-19 Blood Clots". JAMA 325 (5): 425. doi:10.1001/jama.2020.25699. PMID 33528515.

- ↑ Moyer, M.W. (19 May 2020). "What We Know About the Covid-Related Syndrome Affecting Children". The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/05/19/parenting/pmis-coronavirus-children.html. Retrieved 19 May 2020.

- ↑ Fischer, K. (18 May 2020). "What to Know About PMIS, the COVID-19-Linked Syndrome Affecting Children". Healthline. https://www.healthline.com/health-news/what-to-know-pmis-syndrome-linked-to-covid-19-affects-children. Retrieved 19 May 2020.

- ↑ MacMillan, C. (14 July 2021). "Researchers Continue to Find Clues About MIS-C". Yale Medicine. Yale University. https://www.yalemedicine.org/news/multisystem-inflammatory-syndrome-in-children-misc-covid-kids. Retrieved 06 September 2021.

- ↑ Manne, B.K.; Denorme, F.; Middleton, E.A. et al. (2020). "Platelet Gene Expression and Function in COVID-19 Patients". Blood: blood.2020007214. doi:10.1182/blood.2020007214.

- ↑ Dorward, D.A.; Russell, C.D.; Um, I.H. et al. (2020). "Tissue-specific tolerance in fatal Covid-19". medRxiv. doi:10.1101/2020.07.02.20145003.

- ↑ Centers for Disease Control and Preventions (22 February 2021). "Symptoms of Coronavirus". Centers for Disease Control and Preventions. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/symptoms-testing/symptoms.html. Retrieved 06 September 2021.

- ↑ Mayo Clinic Staff (7 October 2020). "COVID-19 (coronavirus): Long-term effects". Mayo Clinic. https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/coronavirus/in-depth/coronavirus-long-term-effects/art-20490351. Retrieved 12 November 2020.

- ↑ Budson, A.E. (8 October 2020). "The hidden long-term cognitive effects of COVID-19". Harvard Health Blog. https://www.health.harvard.edu/blog/the-hidden-long-term-cognitive-effects-of-covid-2020100821133. Retrieved 12 November 2020.

- ↑ Ma, C.; Cong, Y.; Zhang, H. (2020). "COVID-19 and the Digestive System". American Journal of Gastroenterology 115 (7): 1003–6. doi:10.14309/ajg.0000000000000691. PMC PMC7273952. PMID 32618648. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7273952.

- ↑ Van Beusekom, M. (11 November 2020). "Half of recovered COVID-19 patients report lingering fatigue". CUDRAP News & Perspective. University of Minnesota. https://www.cidrap.umn.edu/news-perspective/2020/11/half-recovered-covid-19-patients-report-lingering-fatigue. Retrieved 18 November 2020.

- ↑ 56.0 56.1 56.2 56.3 Simon, N.M.; Saxe, G.N.; Marmar, C.R. (2020). "Mental Health Disorders Related to COVID-19–Related Deaths". JAMA 324 (15): 1493–94. doi:10.1001/jama.2020.19632. PMID 33044510.

- ↑ Savage, M. (28 October 2020). "Coronavirus: The possible long-term mental health impacts". BBC Worklife. https://www.bbc.com/worklife/article/20201021-coronavirus-the-possible-long-term-mental-health-impacts. Retrieved 18 November 2020.

- ↑ Kelland, K. (9 November 2020). "Study Shows COVID-19 Patients at Greater Risk of Mental Health Problems". Insurance Journal. https://www.insurancejournal.com/news/international/2020/11/09/590113.htm. Retrieved 18 November 2020.