Difference between revisions of "Journal:Unravelling the tangled taxonomies of health informatics"

Shawndouglas (talk | contribs) m (Italicizing journal title.) |

Shawndouglas (talk | contribs) (→Notes: Added cat.) |

||

| Line 124: | Line 124: | ||

<!--Place all category tags here--> | <!--Place all category tags here--> | ||

[[Category:LIMSwiki journal articles (added in 2015)]] | |||

[[Category:LIMSwiki journal articles (all)]] | [[Category:LIMSwiki journal articles (all)]] | ||

[[Category:LIMSwiki journal articles on health informatics]] | [[Category:LIMSwiki journal articles on health informatics]] | ||

Latest revision as of 21:03, 28 December 2015

| Full article title | Unravelling the tangled taxonomies of health informatics |

|---|---|

| Journal | Informatics in Primary Care |

| Author(s) | Barrett, David; Liaw, S. T.; de Lusignan, Simon |

| Author affiliation(s) | Department of Nursing, University of Hull; UNSW Medicine; Department of Health Care Management & Policy, University of Surrey |

| Primary contact | Email: d.i.barrett@hull.ac.uk |

| Year published | 2014 |

| Volume and issue | 21 (3) |

| Page(s) | 152–155 |

| DOI | 10.14236/jhi.v21i3.78 |

| ISSN | 2058-4563 |

| Distribution license | Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International |

| Website | http://hijournal.bcs.org/index.php/jhi/article/view/78/109 |

| Download | http://hijournal.bcs.org/index.php/jhi/article/download/78/110 (PDF) |

Abstract

Even though informatics is a term used commonly in healthcare, it can be a confusing and disengaging one. Many definitions exist in the literature, and attempts have been made to develop a clear taxonomy. Despite this, informatics is still a term that lacks clarity in both its scope and the classification of sub-terms that it encompasses.

This paper reviews the importance of an agreed taxonomy and explores the challenges of establishing exactly what is meant by health informatics (HI). It reviews what a taxonomy should do, summarises previous attempts at categorising and organising HI and suggests the elements to consider when seeking to develop a system of classification.

The paper does not provide all the answers, but it does clarify the questions. By plotting a path towards a taxonomy of HI, it will be possible to enhance understanding and optimise the benefits of embracing technology in clinical practice.

Keywords: clinical informatics, health informatics, taxonomy

The problem of the tangled taxonomies

Informatics: a word that conjures up a host of definitions, applications and systems. Within healthcare, ‘informatics’ is used as a descriptor in a way that can be confusing and in some cases disengaging.[1] This confusion stems partly from the meaning of the word itself (Box 1), and partly from the plethora of sub-terms, sub-definitions and applications that can be connected to it. The focus of many of these sub-terms is on the technologies used in the delivery of care, providing a conceptual overlap between health information management and health (clinical) informatics. So, what is informatics?

Where do different concepts fit and interrelate? And does it really matter if we do not know?

|

Terms such as digital health, eHealth, mHealth and technology-enabled care are used interchangeably and without any clear boundaries or criteria. It can be argued that this is unimportant, and that because specific applications (such as electronic patient records, electronic prescribing and clinical decision support software) can be described with some clarity, the need for clear categorisation is redundant. We would refute this. In any area of healthcare, a clear taxonomy — essentially, a system of classification — is necessary to underpin the commissioning and provision of services, and for documentation of care, workforce development and evidence-based generation. Without clarity, we struggle to describe to others what health informatics (HI) means for them and what the benefits are to patients, practitioners and organisations.

Definitions of health informatics

It is hard to develop a taxonomy without first defining the area you are looking to classify. Fortunately, overarching definitions of HI vary little across organisations and countries. Most are centred on the principle that HI relates to information and communication technologies applied to healthcare to achieve desired outcomes.

For example, the UK Department of Health definition of HI is

The knowledge, skills and tools that enable information to be collected, managed, used and shared to support the delivery of healthcare and to promote health and wellbeing.[2]

The Australian Health Informatics Education Council has a much more scientific, discipline-based definition, describing HI as

...the application of information science and computer science to healthcare[3]

A recent, comprehensive, yet succinct definition of clinical informatics encompasses much of the scope of HI:

Clinical informatics is not simply “computers in medicine” but rather is a body of knowledge, methods and theories that focus on the effective use of information and knowledge to improve the quality, safety and costeffectiveness of patient care as well as the health of both individuals and populations.[4]

These definitions align on the principle and purpose of informatics, but – as is the case with most definitions – do not provide any detail or clarity on the boundaries or component elements of HI.

A discussion of the scope of HI is therefore needed, possibly even debating whether specific applications fall under the informatics umbrella. For example, do any or all of the following applications form part of HI?

- ePrescribing

- Remote blood pressure monitoring

- The provision of peer support via social media

Existing taxonomies

Attempts have previously been made to create a taxonomy for HI and associated areas:

- Dixon, McGowan and colleagues progressively developed first a glossary of terms aimed at novices to health information[5] and then a taxonomy for health information technology[6], finally looking to enhance this by adapting their taxonomy according to users’ preferred search terms.[7] However, their approach was based on the scope of library classifications such as Medical Subject Headings. Others have seen the development of similar vocabularies as a key piece of the infrastructure to enable the definition of HI as a discipline.[8]

- Boonstra and Broekhuis proposed a taxonomy focussed on the barriers to the adoption of HI applications (specifically, computerised medical records). They identified eight key elements: (1) financial, (2) technical, (3) time, (4) psychological, (5) social, (6) legal, (7) organisational and (8) change process limitations.[9] Such a taxonomy might be applied more widely to HI and beyond.

- Taxonomies have also been described for the HI platforms, HealthGrids, which may enable linkage of multiple informatics systems.[10] These highlight how systems used in health lag behind those routinely used in business.

- Stagger and Thompson suggested that there might be (1) technology-, (2) role- and (3) concept-orientated definitions of HI.11 In the Staggers and Thompson taxonomy, terms such as telehealth, eHealth and mHealth are simply technology-orientated definitions, focussed purely on the devices or media that serve as facilitators of care. Role-orientated definitions might relate to the need to use informatics within a specific clinical discipline – for example, primary care informatics[11] – or may be linked to an individual’s role. For example, the term ‘health informatician’ may be used to describe someone with HI skills who may be specially trained or have relevant experience. (A recent JAMA paper described the establishment of clinical informatics as a subspecialty.[4]) Individuals may have a specific professional role (e.g. nursing or pathology informatics), or a generic, organisational role, such as chief clinical information officer.[12] Finally, concept-orientated definitions of informatics attempt to define what HI is, some deliberately opting for conceptually defining informatics as a science that should be research and evidence based.[13]

Defining the broad scope of HI is only the first step on the road to a clear taxonomy. Assuming that HI encompasses more specific concepts such as eHealth, telemonitoring and telemedicine, it is necessary to explore how these (and others) are categorised and how they interrelate.[14]

To move this debate forward, we need to explore the relevant concepts that help define HI, providing some clarity and allowing its development as a science. At the crudest level, these concepts can be viewed as a checklist to be considered in any future attempts at developing a taxonomy of HI.

Dimensions of health informatics

Multidisciplinary

HI is a multidisciplinary science, which implies an intuitive relationship to the multidisciplinary health care team in promoting information-enhanced integrated care.[15] Herein lies another problem of tangled taxonomies as we see it today. Though both HI and health care are inherently multidisciplinary in approach, both can involve very different groups of professionals with their own skill sets, approaches to practice and views on terminology. This exacerbates the complexity of classification and implementation.

Interdisciplinary

Along with technical and conceptual definitions and associated issues, there are inter-professional and inter-disciplinary questions to be addressed in any taxonomy. In an ideal world, HI could well be the unifying mechanism for the health professions, and conceptual research in this area could lead to more coordinated and accessible care. To date, interdisciplinary initiatives extend little beyond educational establishments.[16][17]

Patient focus

Being patient centred has long been part of health care. Informatics has the potential to empower patients to manage their health, with or without the input of the clinical professions.[14][18] However, a taxonomy needs to acknowledge and clarify the role of different elements of informatics in terms of the role of — and impact on — patients.

Level of expertise and sophistication

Within HI, we must also be able to describe the level of expertise and sophistication of people working within the discipline. To date, most attempts to do this have been at the regional or national level.[4][19]

Technology application

HI is dependent on the implementation and adoption of a growing range of technological solutions. From data input devices (such as digital pens) to user interfaces on a multitude of platforms, HI comes in many shapes and sizes. Device-orientated terms (such as mHealth) exist in the literature and may figure within any taxonomy.

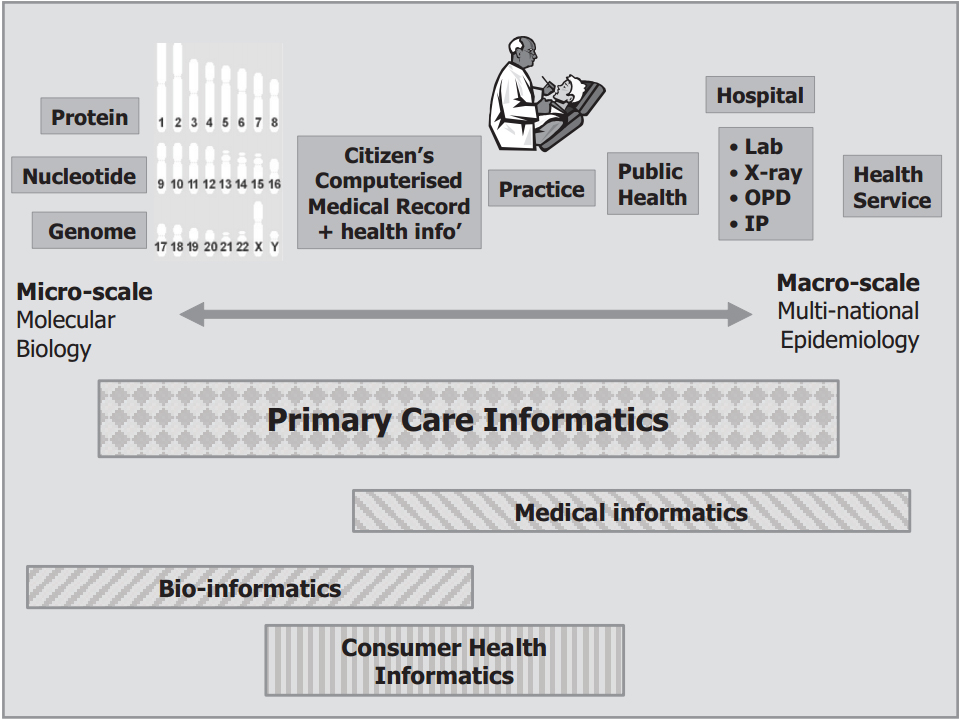

Data granularity

Some taxonomies of HI have looked at the granularity of the data that are processed. Some of the motivation for this was to avoid the separation of HI from bioinformatics.[20] Regardless, the scope of HI can be described using a taxonomy related to the degree of granularity as the primary subject of interest (Figure 1).

Recognition, academic and learned societies

Courses, appointments and societies (national or specialist) recognised by international groups and journals all provide markers of what defines HI and its subspecialties. Regulation may be required to ensure that its processes are safe for patients[21], and existing mechanisms to organise, verify, accredit and recognise interventions may need acknowledging in any taxonomy.

Figure 1. A taxonomy of HI based on the granularity of the primary focus of the HI subspecialty

Summary - Untangling the taxonomies

HI is evolving as a multidisciplinary science and should be defined as such. Conceptual research and development is required to optimize and guide taxonomical evolution over the coming years.

Through journals such as Informatics in Primary Care, some consensus needs to be reached regarding the scope, definitions and categories of applications. Clarity will aid clinicians, researchers, commissioners, managers and educators to understand HI, build the evidence base, implement services and share knowledge. The development of an agreed taxonomy is not necessarily an end in itself, but is a means to an end: greater clarity provides greater understanding and underpins future research that informs clinicians on how best to use technology to enhance the delivery of health care.

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Hersh, W. (2009). "A stimulus to define informatics and health information technology". BMC Medical Informatics and Decision Making 9: 24. doi:10.1186/1472-6947-9-24. PMID 19445665.

- ↑ Department of Health (October 2002). "Making Information Count: A Human Resources Strategy for Health Informatics Professionals". The Health and Social Care Information Centre. http://systems.hscic.gov.uk/icd/whatis.

- ↑ Australian Health Informatics Education Council (November 2011). "Health Informatics: Scope, Careers and Competencies - Version 1.9" (PDF). http://www.ahiec.org.au/docs/AHIEC_HI_Scope_Careers_and_Competencies_V1-9.pdf.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 Detmer, D.E.; Shortliffe, E. (2014). "Clinical informatics: prospects for a new medical subspecialty". JAMA 311 (20): 2067–8. doi:10.1001/jama.2014.3514.

- ↑ Cravens, G.D.; Dixon, B.E.; Zafar, A.; and McGowan, J.J. (2008). "A health information technology glossary for novices". AMIA Annual Symposium Proceedings: 917. PMID 18998981.

- ↑ Dixon, B.E.; Zafar, A.; McGowan, J.J. (2007). "Development of a taxonomy for health information technology". Studies in Health Technology and Informatics 129 (Pt 1): 616–20. PMID 17911790.

- ↑ Dixon, B.E.; McGowan, J.J. (2010). "Enhancing a taxonomy for health information technology: an exploratory study of user input towards folksonomy". Studies in Health Technology and Informatics 160 (Pt 2): 1055–9. PMID 20841845.

- ↑ Sperzel, W.D.; Broverman, C.A.; Kapusnik-Uner, J.E.; Schlesinger, J.M. (1998). "The need for a concept-based medication vocabulary as an enabling infrastructure in health informatics". Annual Symposium Proceedings: 865–9. PMID 9929342.

- ↑ Boonstra, A.; Broekhuis, M. (2010). "Barriers to the acceptance of electronic medical records by physicians from systematic review to taxonomy and interventions". BMC Health Services Research 10: 231. doi:10.1186/1472-6963-10-231.

- ↑ Naseer, A.; Stergioulas, L.K. (2010). "HealthGrids in health informatics: a taxonomy". In Khoumbati, K.; Dwivedi, Y.; Srivastava, A.; Lal, B. Handbook of Research on Advances in Health Informatics and Electronic Healthcare Applications: Global Adoption and Impact of Information Communication Technologies. Medical Information Science Reference. pp. 124–43. doi:10.4018/978-1-60566-030-1.ch008.

- ↑ Staggers, N.; Thompson, C.R. (2002). "The evolution of definitions for nursing informatics: a critical analysis and revised definition". Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association 9: 255–61. doi:10.1197/jamia.M0946.

- ↑ Whatling, J. (September 2011). "Chief Clinical Information Officer campaign (CCIO) launch". British Computer Society (BCS). http://www.bcs.org/content/conWebDoc/41603.

- ↑ de Lusignan, S. (2003). "What is primary care informatics?". Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association 10 (4): 304–9. doi:10.1197/jamia.M1187. PMID 12668690.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 Wyatt, J.C.; Sullivan, F. (2005). "eHealth and the future: promise or peril?". British Medical Journal 331 (7529): 1391–3. doi:10.1136/bmj.331.7529.1391. PMID 16339252.

- ↑ Geissbuhler, A.; Kimura, M.; Kulikowski, C.A.; Murray, P.J.; Ohno-Machado, L.; Park, H.A. et al. (2011). "Confluence of disciplines in health informatics: an international perspective". Methods of Information in Medicine 50 (6): 545–55. doi:10.3414/ME11-06-0005. PMID 22146917.

- ↑ Demiris, G. (2007). "Interdisciplinary innovations in biomedical and health informatics graduate education". Methods of Information in Medicine 46 (1): 63–6. PMID 17224983.

- ↑ Kushniruk, A.; Lau, F.; Borycki, E.; Pratti, D. (2006). "The School of Health Information Science at the University of Victoria: towards an intergrative model for health informatics education and research". Yearbook of Medical Informatics: 159–65. PMID 17051310.

- ↑ Alamantariotou, K.; Zisi, D. (2010). "Consumer health informatics and interactive visual learning tools for health". International Journal of Electronic Healthcare 5 (4): 414–24. doi:10.1504/IJEH.2010.036211.

- ↑ McCullagh, P.; McAllister, G.; Hanna, P.; Finlay, D.; Comac, P. (2011). "Professional development of health informatics in Northern Ireland". Studies in Health Technology and Informatics 169: 218–22. PMID 21893745.

- ↑ Maojo, V.; Kulikowski, C. (2006). "Medical informatics and bioinformatics: integration or evolution through scientific crises?". Methods of Information in Medicine 45 (5): 474–82. PMID 17019500.

- ↑ Rigby, M.; Forsström, J.; Roberts, R.; Wyatt, J. (2001). "Verifying quality and safety in health informatics services". British Medical Journal 323 (7312): 552–6. doi:10.1136/bmj.323.7312.552. PMID 11546703.

Notes

This presentation is faithful to the original, with only a few minor changes to presentation.